Winterthur events

The term Winterthur events refers to a series of paint, incendiary and explosive attacks as well as the subsequent wave of arrests within the youth scene in the Swiss city of Winterthur in 1984.

Prehistory and political environment

The youth riots in Switzerland at the beginning of the 1980s also included the Zurich opera house riots in May 1980. In relation to this, the Neue Zürcher Nachrichten wrote in July 1980 that the clocks in Winterthur went a little differently and that young people weren't rushing around naked to protest and there are holiday events "where rebellious young people are also able to get enthusiastic about constructive participation".

On October 18, 1980 there were demonstrations in Winterthur against the delivery of heavy water systems , which could also be used for the construction of atomic bombs , by Sulzer to the Argentine military dictatorship at the time . Two and a half weeks after the demonstration, two alleged participants were placed in solitary confinement . When a witness then testified that one of the alleged participants was not even in Winterthur at the said time, the district attorney had him arrested for false statements. Only when other witnesses confirmed his testimony did both of the arrested people have to be released. The second arrested participant was the painter Aleks Weber , later one of the main actors in the Winterthur events from 1984. He was sentenced to prison after nine days in solitary confinement for warning of police spies during the demonstration . This judgment was already criticized by the press at that time, said the then SVP National Councilor Erwin Akeret in the conservative Weinländer Tagblatt that such disproportionate measures were ideally suited to fuel the hitherto calm climate. As a result of this ruling, the Winterthur youth center excluded district attorney Eugen Thomann from its sponsoring association.

Shortly thereafter, Weber was arrested again with five other young people during a raid on the youth center. The arrested were placed in solitary confinement and the lawyers were banned from contact. The democratic jurists protested against this , whereupon the later Federal Councilor Rudolf Friedrich defended the judiciary's approach. It is unclear what exactly the prosecution wanted to achieve with the arrests.

A year later, protests were made against the weapons exhibition W81 in the Eulachhalle in Winterthur . The carpet of people, where the trade fair visitors symbolically had to walk over corpses, was sprayed with liquid manure by an anonymous “vigilante group” who was never called to account . According to the Tages-Anzeiger journalist Kathrin Bänziger, "within a very short time a zero-tolerance climate had built up in Winterthur against protests of the youth movement that formed the breeding ground for later events".

Course of events in Winterthur

Attacks in Winterthur

Between 1981 and 1983 there were also a total of 16 different attacks on construction sites, offices, army vehicles and other objects in Winterthur. But the attacks in Winterthur at the time did not all come from the later so-called «Wintis» prisoners, a 22-year-old domestic worker was convicted of 13 arson earlier, and not all other incidents can be assigned to the «Wintis». On March 18, 1983, the Winterthur town hall was also the target of a Molotow cocktail .

On June 17, 1984, a catenary on the Winterthur – Zurich railway line near Rossberg was short-circuited in a media-effective manner, which delayed the journey home of visitors to the Swiss Federal Gymnastics Festival (in the run-up to the Gymnastics Festival, the city had spray works removed for CHF 73,000 , even without asking private landowners, to leave the cleanest impression possible). In the two following nights, an arson attack was attempted on the Winterthur old age allowance and on a construction trailer; on June 21, the federal attorney's office was brought in. Under the direction of Hans Vogt, the agency started investigations into danger from explosives and also carried out telephone surveillance , observation and waste analysis. Even at this time, the police repeatedly entered shared apartments without a search warrant .

One month after the investigation began, there was an attack with black powder on the building of the Hypothekar- und Handelsbank at Stadthausstrasse 14. This resulted in property damage of 11,500 francs.

On August 7, 1984 the series reached its climax with the bomb attack on Federal Councilor Rudolf Friedrich's house ; As in the other attacks in recent years, no people were injured. According to the indictment, there was property damage of around 20,000 francs, mainly due to a broken living room window. The attack dissipated widespread media coverage and also forced the authorities to act. The NZZ spoke of an act of vandalism with “ terrorist and anarchist features”. Friedrich, who had initially assumed a lightning strike, spoke of an attack on the "liberal social order". In the aftermath there were attacks on an office barrack owned by the Rieter company on August 20 (property damage: approx. 14,000 francs) and on the technical center on September 21 (approx. 4,000 francs).

Arrests in November 1984

On November 20, 1984, 32 young people were arrested in three shared apartments in the largest police operation ever carried out in the canton of Zurich, called “Bottleneck”. After this wave of arrests, the Landbote reported in Winterthur with noticeable relief and praised the police. The large-scale police action also met with criticism from the press. For example, apartments above the alternative restaurant "Widder" were also searched for which no search warrant was available. Eugen Thomann, head of the "Bottleneck" campaign and then police commander of the city police, later rated the mass arrests as a success, as things had become quiet in Winterthur after them and this was proof that the police had arrested the right people. The police have also reacted to arrest warrants from the Federal Prosecutor's office and, up to the “bottleneck” campaign, a total of half a million Swiss francs in damages from 30 different offenses have accumulated.

One week after the "bottleneck" campaign, on November 27, Hans Vogt, chief investigator of the federal police, shot himself with his service pistol. There are two versions of the reason for his suicide: On the one hand, Vogt had jokingly registered in a Winterthur hotel with the destination “Beirut” and this would have been reported to Bern by the Zurich canton police , with whom he was not very popular. On the other hand, the Federal Prosecutor's Office simply spoke of an illness that had nothing to do with the events in Winterthur. Vogt had also conducted unrecorded interrogations because of slow investigations and is considered to be the author of the anonymous letter that Gabi S. had received and which was vulgarly directed against her friend and one of the main suspects arrested, Aleks Weber . In Vogt's farewell letter, he named problems with the cantonal police as the reason for his suicide and forbade several cantonal police officers named by name from attending his funeral.

Gabi S.

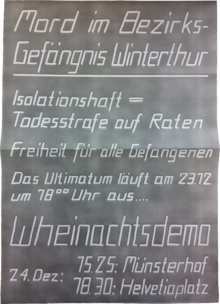

The 23-year-old Gabi S. was arrested the day before the "Bottleneck" police operation and was the friend of the main suspect Aleks Weber , but she herself was not one of the main suspects and the only thing the police could do was fill her with two glasses of yoghurt with red paint against the newly renovated St. Peter and Paul Church , which she also confessed. It was from the beginning, like other detainees also in solitary confinement held and restricted in their rights. Her lawyer Cornelia Kranich was able to see Gabi S. for the first time and for the only time after two and a half weeks in custody on December 6, and this only under the observation of a canton police officer. On December 12, her parents protested to the responsible public prosecutor, Jörg Rösler, against their conditions of detention, pointing out the consequences of solitary confinement and the unusual restrictions on visits and legal rights. Attention was also drawn to the prison conditions of the so-called "Wintis" in various leaflets and others. On December 15, 1984, there was a demonstration in Winterthur against the inhumane conditions in the prisons.

During her imprisonment, Gabi S. was shown several times the anonymous letter that was later assigned to the senior federal official, Hans Vogt, and that she had received before her arrest and that defamed her boyfriend. The attempt was made to play her off against her boyfriend, who would allegedly consider her to be the "last shit". She complained about this behavior by the police for most of the 45 minutes when she first visited her lawyers on December 6th. When her friend Aleks Weber was arrested, the lie was spread that he was found in bed with another woman.

On December 17 and 18, after four weeks in solitary confinement, Gabi S. was interrogated by two federal police officers who had specially traveled from Bern for eight to nine hours. They hoped that she would gain new knowledge about possible acts of her friend Aleks Weber - and weeks after that The arrests could hardly be proven to the arrested person. During the interrogation, during which, among other things, she was refused any food, she testified that Res S. had possibly written a letter of confession to the attack on Friedrich's house - the letter, incidentally, never appeared. After the interrogation, Gabi was told that the district attorney would now inform all other prisoners that she had made a confession and betrayed her friends. According to an open letter from five fellow prisoners, after the last interrogation, Gabi S. ' Cell heard sobs and screams for a long time. The following day Gabi S. was found hanged with an immersion heater in her cell in the Winterthur district prison. At a press conference one day after Gabi's suicide, the lawyers of the nine remaining detainees accused the authorities of wanting to soften the detainees “at all costs, including those of corpses”. Actually, the parents of the detainees should also have participated in the press conference, but due to a leaflet by a vigilante group, they left it for fear of reprisals. The authorities defended their approach and referred to enormous pressure from outside that would have weighed on Gabi S. - also from her lawyers. Ueli Arbenz from the Winterthur district attorney also claimed at the press conference that Gabi S. had once again confirmed an alleged confession of "extremely massive damage to property" in her suicide note. However, in the real farewell letter, which later was Gabi S. ' Mother was handed over, only that she had neither set fire nor made bombs, there was no question of a confirmed confession. Shortly before the interrogation, district attorney Arbenz admitted in an interview that the authorities had arrested some people even though they knew they were innocent.

This practice, known as detention , is prohibited in Switzerland. The detainees' lawyers also made various allegations, including the inadmissible conditions of detention, the lack of evidence for the arrests and the restrictions on visiting rights. They were allowed to see their clients for the first time after 23 days of pre-trial detention and the delivery of Gabi S.'s death notice to his friend was monitored and recorded by two officers. The accusation that the suicide was foreseeable was dismissed by the public prosecutor Rösler and even after this incident he considered increased attention in this regard as “not necessary”.

Nevertheless, there was a reaction to Gabi S.'s suicide: Shortly after Gabi S.'s death, most of the other arrested persons were released from custody. They installed a vigil in Winterthur's Marktgasse near the Justice Fountain . On December 27, 1984, a manure attack was carried out by three strangers on the vigil with about 20 people, which was broken off a little later after another threat. In February 1985, only Aleks Weber and the second main suspect, Res S., arrested on the run in Geneva, were still imprisoned; the police had to release the rest of those arrested.

Lawsuits against Aleks Weber

More than a year after the release of the rest of the arrested, public prosecutor Pius Weber brought charges against Aleks Weber on April 3, 1986 and charged him with six incendiary and explosive attacks in a circumstantial trial . In the indictment, there was talk of "sheer terror with property damage in the millions", while at the same time he could only credit Weber with a specific amount of damage of 36,000 francs. The remainder of the charge was based on bomb-making instructions found in Weber's shared apartment and propellant particles in his studio that matched those of the bombs. Shortly before the verdict was announced, the journalist Erich Schmid published the first edition of his book Verhör und Tod in Winterthur and his research received wide media attention.

The artist Aleks Weber was on 16 September 1986 by the Zurich High Court to eight years in prison convicted. This judgment, perceived as exaggerated, again met with massive criticism. Weltwoche described the judgment as “politically motivated” and the country messenger reported a “outrageous judgment”. The Zurich Court of Cassation later overturned this judgment because of arbitrary evidence , so that Weber was released on July 23, 1987 after three years of solitary confinement. In a new trial before the higher court, he was held responsible for three bomb attacks, but the attack on the house of Federal Councilor Friedrich could not be proven and Weber was sentenced to four years in prison.

On January 15, 1988, the “Winterthur Declaration” was published by an association of parents, lawyers and those affected. In it, the entire approach by the police and public prosecutor was again criticized and the balance sheet was drawn up: of the 32 criminal proceedings opened, only three led to convictions relating to the bomb attacks. The other proceedings resulted in nine convictions for spraying, four acquittals and twelve suspensions. In order to make the charges for spraying possible at all, the Winterthur road inspector had to file a criminal complaint beforehand at the request of the canton police for each spraying shop and document this photographically, even though such crimes were actually the responsibility of the city police . In 1975, the sum of 450 to 500 property damage accumulated, whereby, for example, three different colors had to be recorded as three different criminal offenses on a small area in a Wülflinger underpass at the behest of the canton police.

On August 19, 1989, Aleks Weber was arrested again on the fringes of a violent demonstration in Zurich and sentenced to a fortnight unconditionally for calling for violence. Two police officers incriminated him while two witnesses exonerated him in court. In the media reports, this judgment was seen as the defeat of the Zurich judiciary, which wanted to take revenge on Weber. Weber died on April 14, 1994 in Winterthur of complications from his AIDS illness.

Litigation against Res S.

Res S. was also released shortly after Weber's first dismissal by order of the higher court after an expert opinion had determined that he could not be clearly assigned as the author of the letters of confession that he was accused of. On December 11, 1989, S. was sentenced to seven years in prison by the Zurich Higher Court in a further circumstantial trial. This judgment was also questioned by the country messenger, among others, as it was based only on a chain of circumstantial evidence. The higher court upheld his judgment in a second trial on February 8, 1990. The judgment of the higher court against S. was overturned in July 1992, like the judgment against Aleks Weber, by the court of cassation in Zurich because the higher court failed to observe the rights of the defense and paid insufficient attention to the arguments of the defense. The High Court then sentenced him to 3 years and 9 months in prison in a third trial. This judgment was also overturned by the Court of Cassation, as the Higher Court once again paid too little attention to the exculpatory evidence for S. In the fourth and final appeal process before the Higher Court, Res S. was sentenced to 18 months in prison on May 19, 1995.

Because of inadmissible conditions of detention during the pre-trial detention in the Winterthur district prison, Res S. moved with his lawyer before the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg . In a judgment in June 1991, the latter agreed with him, and Res S. was awarded satisfaction in the amount of 2,500 francs as well as legal compensation of 12,500 francs. Res S. was never able to recover mentally from pre-trial detention and years later was still in psychiatric treatment and unable to work. For his overly long imprisonment of 1291 days, he never received any compensation from the state.

rating

The violence of the police measures was due, among other things, to the fact that the authorities feared youth unrest similar to that in the city of Zurich in the early 1980s ( opera house riots ). The wave of arrests was successful in that it practically smashed the radical youth scene in Winterthur. From a legal point of view, however, the suspicions against most of the arrested were not substantiated. While mostly right-wing circles welcomed the tough crackdown by the authorities, left circles tended to criticize the arrests as disproportionate or even illegal (accusation of flexural detention), especially after Gabi S.'s suicide while in custody. Questions were raised in particular by the anonymous letter to Gabi S., the author of which was probably a senior detective who died of suicide during the investigation. The judgments of the Zurich Higher Court have been overturned several times by the Court of Cassation because of inadmissible evidence and the inadmissible conditions of detention have been condemned by the European Court of Human Rights .

Work-up

The critical processing of the Winterthur events was carried out in particular by the journalist Erich Schmid , reporter and court reporter for the Tages-Anzeiger since 1980 . Schmid published the book Verhör und Tod in Winterthur in 1986 . The book provided the template for the documentary of the same name by Richard Dindo (2001). Rudolf Gerber, the former editor of that time, "especially the authorities responsible line" Landbote 2007 that the confessed Landbote "not too well" to hinschaute times, but this is corresponded to the spirit of the times. The then mayor Urs Widmer found in 2008 that the whole thing had been "a very tedious matter", in which the judiciary had not played a particularly brilliant role, at that time we should have "talked to each other more".

literature

- Erich Schmid : Interrogation and death in Winterthur. 250 pages, 3rd editions, Limmat Verlag, 1986/87 revised and expanded edition 2002.

- Bettina Dyttrich: Winterthur events in the crossfire Interrogation and death in Winterthur: a book is being filmed. In: WOZ The weekly newspaper . No. 14/2002, pp. 17-18.

- Christof Dejung: Riots in Winterthur. Part 1–3. WOZ The weekly newspaper. 2004.

- Pig for pig - Päng. ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- The jump into the wall. ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- The time after the immersion heater. ( Memento from September 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Thomas Möckli: A piece of unprocessed Winterthur history: Winterthur events: November 20, 1984. In: Winterthur yearbook. Winterthur. 50 (2003). Pp. 52-59.

Movies

- Interrogation and Death in Winterthur , documentary based on the title of the book by Erich Schmid , Switzerland, 2002, director: Richard Dindo .

Web links

- Winterthur events in the 1980s in the Winterthur glossary.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Christof Dejung : Pig for pig - Päng. In: WOZ The weekly newspaper . November 18, 2004, archived from the original on September 30, 2007 ; Retrieved July 8, 2016 .

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. Pp. 10-11.

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. Pp. 11-12.

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 92.

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 24.

- ↑ Explosives attack on Rudolf Friedrich's house . In: The Landbote . Ziegler Drucks- und Verlags-AG, Winterthur August 8, 1984, p. 1 .

- ^ A b c Laura Rutishauser: "Recognition for our police" . In: The Landbote . Ziegler Drucks- und Verlags-AG, Winterthur July 26, 2007, p. 13 .

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 50.

- ↑ a b Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 98.

- ↑ Richard Dindo: Interrogation and Death in Winterthur , documentary film, Switzerland 2002. (46 min.)

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 160.

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 200.

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 161.

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 58.

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 60.

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 144.

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 198.

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 120.

- ↑ Richard Dindo: Interrogation and Death in Winterthur , documentary film, Switzerland 2002. (34 min.)

- ^ After suicide in custody: lawyers attack the authorities . In: Blick (newspaper) . Ringier, December 20, 1984.

- ↑ Richard Dindo: Interrogation and Death in Winterthur , documentary film, Switzerland 2002. (36 min.)

- ↑ Farewell letter: «The easiest way» . In: The Landbote . Ziegler Drucks- und Verlags-AG, Winterthur December 19, 1984, p. 11 .

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 140.

- ↑ a b c Christof Dejung : The jump into the wall. In: WOZ - The weekly newspaper . November 25, 2004, archived from the original on September 30, 2007 ; accessed on March 15, 2014 .

- ↑ "Suicide reflects investigation procedures" . In: The Landbote . Ziegler Drucks- und Verlags-AG, Winterthur December 20, 1984, p. 11 .

- ↑ Manure raid against «vigil» . In: The Landbote . Ziegler Drucks- und Verlags-AG, Winterthur December 28, 1984.

- ↑ Erich Schmid: Interrogation and death in Winterthur. P. 21.

- ↑ Christof Dejung: The time after the immersion heater. In: WOZ - The weekly newspaper . December 2, 2004, archived from the original on September 30, 2007 ; accessed on March 15, 2014 .

- ^ A b Thomas Möckli: A piece of unprocessed Winterthur history: Winterthur events: November 20, 1984. In: Winterthur year book. Winterthur. 50 (2003). P. 53.

- ↑ Alex Hoster: A contemporary witness of Winterthur history . In: The Landbote . Winterthur November 29, 2008, p. 16 .