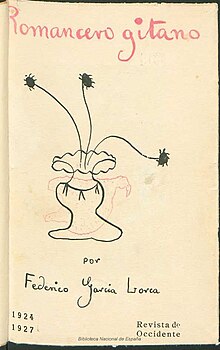

Romancero gitano

Romancero gitano ( gypsy romances ) is a collection of poems by Federico García Lorca .

background

In the 1920s, starting in France, surrealism also spread to Spain. Artists in Spain found in him a form of expression against the pressure of an outmoded Catholic morality and feudal power structures under the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera . Through his friendship with Salvador Dalí and trips to Catalonia in the early 1920s, Federico García Lorca gained access to this art direction.

Lorca was a deep connoisseur of the literary tradition of Spain and especially of its Andalusian homeland. He knew the traditional medieval romances , which developed in a lyrical direction in the seventeenth century under the influence of Lope de Vega , Luis de Góngora, and others.

A romance has eight-syllable verses with assonant rhyme. It offers the poet great freedom because it allows impure rather than perfect rhymes. Traditionally, romance told historical events, often with the aim of preserving or promoting national values. Readers and listeners expected a linear story about a significant person or a special event from the story that was consistent with prevailing values. It is a specifically Spanish form of dramatic poetry. Romancero gitano breaks with this tradition. Even the title is an oxymoron : while Romance refers to the form that is most rooted in Spanish history, the Gitano is generally understood to be nomadic and has no traditional history. He stands for a marginalized people. García Lorca undermined the traditional affirmative function of the heroic narrative by writing about nameless antiheroes from this people. The experimental surrealist content of the poems deepens this break. With the choice of the traditional, popular form, García Lorca lured onto new paths.

content

The poems

The Romancero consists of the following 18 poems:

| title | translation | dedication | ||

| 1 | Romande de la luna, luna | Romance to the moon, the moon | A Conchita García Lorca | |

| 2 | Preciosa y el aire | Preciosa and the wind | A Damaso Alonso | |

| 3 | Reyerta | Violent struggle | A Rafael Méndez | |

| 4th | Romance sonámbulo | Somnambulistic romance | A Gloria Giner y a Fernando de los Ríos |

|

| 5 | La monja gitana | The Gitana nun | A José Moreno villa | |

| 6th | La casada infiel | The unfaithful wife | A Lydia Cabrera y a su negrita |

|

| 7th | Romance de la pena negra | Romance from black grief | A José Navarro Pardo | |

| 8th | San Miguel Granada |

Saint Michael Granada |

A Diego Bigas de Dalmau | |

| 9 | San Rafael Cordoba |

Saint Raphael Cordoba |

A Juan Izquierdo Croselles | |

| 10 | San Gabriel Seville |

Saint Gabriel Seville |

A Don Agustín Viñuales | |

| 11 | Prendimiento de Antoñito el Camborio en el camino de Sevilla | The arrest of Antoñito el Camborio on the way to Seville | A Margarita Xirgu | |

| 12 | Muerte de Antoñito el Camborio | The death of Antoñito el Camborio | A José Antonio Rubio Sacristan | |

| 13 | Muerto de amor | Death out of love | A Margarita Manso | |

| 14th | Romance del emplazado | Romance of the summoned | Para Emilio Aladrén | |

| 15th | Romance de la Guardia Civil española | Romance by the Spanish Civil Guard | A Juan Guerrero, Cónsul general de la poesía |

|

| 16 | Martirio de Santa Olalla | Martyrdom of Saint Eulalia | A Rafael Martínez Nadal | |

| 17th | Burla a Don Pedro a caballo Romance con lagunas |

Mockery of Don Pedro on horseback romance with lagoons |

A Jean Cassou | |

| 18th | Thamar y Amnón | Tamar and Amnon | Para Alfonso García Valdecasas |

The original Spanish texts have been in the public domain and available on the Internet since the end of 2006 .

subjects

Federico García Lorca himself described his book with the words:

«(…) El libro es un retablo de Andalucía con gitanos, caballos, arcángeles, planetas, con su brisa judía, con su brisa romana, con ríos, con crímenes, con la nota vulgar del contrabandista, y la nota celeste de los niños Desnudos de Córdoba que burlan a San Rafael. Un libro donde apenas si está expresada la Andalucía que se ve, pero donde está temblando la que no se ve. (...) Un libro antipintoresco, antifolclórico, antiflamenco. "

“(...) the book is an altarpiece of Andalusia with gitanos, horses, archangels, planets, with its Jewish breeze, with its Roman breeze, with rivers, with crimes, with the vulgar image of the smuggler and the heavenly image of the naked children of Cordoba making fun of the Archangel Raphael. A book in which the visible Andalusia is hardly expressed, but the invisible vibrates. (...) An anti-picturesque, anti-folklore, anti-flamenco book. "

He conveyed an idealized picture of the country and the Gitanos . He called them the most sublime, deepest and most aristocratic people of his homeland, and consequently calls them país gitano . This idealized “altarpiece of Andalusia” spans the country's themes from natural to mythical and religious, from the present to history. The poems tell of the landscape, its flora and fauna, its inhabitants and their violent conflicts, breaches of faith and accounts.

In addition, the Roman, Jewish, Christian and, with sparse allusions, the Muslim tradition of the country are addressed in the poems:

- The reference to Rome is expressed in the poem San Rafael . It describes the monumental beauty of the bridge that Emperor Augustus had built and refers to the Roman god Neptune . In Martirio de Santa Olalla , Roman soldiers in their armor, a consul, centurions , statues and the goddess Minerva appear. The poem is based on Prudentius ' story of the torture of Saint Eulalia . The serene acceptance of death, which is thematized in the poem Romance del emplazado , for example , is reminiscent of the Roman philosopher Seneca .

- Jewish themes can be found in Thamar y Amnon , the poem of the incestuous love affair of the two children of King David , and again in San Rafael , where the archangel Raphael to Tobias passes on his long journey.

- Most of all, however, the Christian element stands out. The motif of the passion is represented in numerous places , for example in Reyerta and in San Gabriel . Antoñito el Camborio, like Jesus , suffers arrest and death. The archangels stand by the doomed, the Blessed Virgin and Saint Joseph heal Gitanos who were wounded by the Guardia Civil , and there is no lack of allusions to other Christian saints myths.

The stories are set in the great Andalusian cities of Cordoba , Seville and Granada . In the mountains of Cabra, near Córdoba, the stabbing takes place in the poem Reyerta , and from there comes the wounded traveler in Romance sonámbulo . In the alleys of the Albaicín , the young nun in La monja gitana suppresses her erotic needs and her longing for freedom. In the olive groves of Jaén , the tierras aceitunas , the romance de la pena negra takes place . Antoñito el Camburio dies on the banks of the Guadalquivir . The location of the action in the other poems is usually not that clear, but the Andalusian character of the place or landscape is always an essential element.

The central characters are the gitanos. García Lorca draws clichés of her way of life: the blacksmith's trade, her devotion to song and dance, her close relationship with horses and her fondness for jewelry. He portrays them as the bearer of a primitive, nature-loving culture, oppressed and marginalized by a civilization whose executive arm is the Guardia Civil . The main themes of his poems arise from the conflict between closeness to nature and civilization: the pursuit of freedom, suffering, violence, love and death. The love of freedom and the instinct of the Gitano, who resists the imposed rules, in connection with the imposed sedentariness inevitably lead to a tragic end. Outbreaks of violence are commonplace under these circumstances. This goes so far that violent death appears as the only natural one in the poems for the Gitano.

In Romancero gitano love has a one-sided expression: the aspect of male sexual desire is almost exclusively in the foreground. The woman is passive. At the same time, love is a vehicle of frustration, with a strong attachment to death. This is clearly expressed in the poems Romance sonámbulo and Muerte de amor . At the same time, there are numerous homoerotic allusions in his poems, for example in the poems San Gabriel and San Miguel :

Un bello niño de junco,

anchos hombros, fino talle,

piel de nocturna manzana,

boca triste y ojos grandes,

nervio de plata caliente,

ronda la desierta calle.

A handsome boy, slender as reeds,

broad shoulders, narrow waist,

skin like an apple in the night,

sad mouth and large eyes,

tendon of hot silver,

wanders the deserted street.

San Miguel lleno de encajes

en la alcoba de su torre,

enseña sus bellos muslos

ceñidos por los faroles.

Saint Michael, wrapped in lace,

in the alcove of his tower,

shows his beautiful thighs

girded with lanterns.

symbolism

Federico García Lorca's poetry is radically symbolist . There is a large amount of literature on the symbols in the Romancero Gitano , with partly different interpretations. Common interpretations of some common symbols are:

- The moon as a symbol of death and freezing.

- The wind as a symbol of male erotic desire.

- The fountain as a symbol of the suppressed passion that finds no fulfillment.

- The horse as a symbol of the unbridled passion that brings the Gitano to death.

- The color green as a symbol of forbidden desire, frustration and sterility.

Several interpreters see in this symbolism a correspondence with elements of the analytical psychology of Carl Gustav Jung .

Translations

Enrique Beck had the exclusive right to translate García Lorca's works. Its translation of the Romancero gitano into German was published in September 1938 by the Swiss publishing house Stauffacher under the title Gypsy Romances with a foreword by Vicente Aleixandre . After Beck's death, the translation rights were transferred to the Heinrich Enrique Beck Foundation in Basel. These translations have met with criticism since the 1950s; Enrique Beck was accused of literary incompetence and his translations clumsiness. In 2000 the foundation finally gave in and allowed other translations.

In 2002 Suhrkamp published a bilingual edition of the Romancero gitano with translations by Martin von Koppenfels and an essay, Act of Violence and Transfiguration in the appendix. In 2007 the Reclam Verlag published a bilingual selection of poems by García Lorca, translated by Gustav Siebenmann, including five poems from the Romancero gitano . In 2008 the Heinrich Enrique Beck Foundation published a two-volume selection of poems translated by Enrique Beck.

reception

The Romancero gitano , published in 1928, became a mass success that made the hitherto little known poet Federico García Lorca famous in one fell swoop. The collection of poems had an influence on the poetry of Spain and Latin America that could hardly be underestimated and became one of the most successful volumes of poetry in world literature.

Readers liked the rhythm and lyrical nature of the poems, and many could recite entire romances of his without being able to explain them. Martin von Koppenfels ascribes this on the one hand to the great historical prestige enjoyed by Spanish romance with its seven centuries of history. Otherwise it would be "... unthinkable (...) that a contemporary of Dada and Surrealism would cause a sensation with gypsy romances on the eve of the Great Depression." On the other hand, Lorca's secret of success lies in the fact that he enjoys playing with the traditional form and classic clichés like that Serve gypsy myth. Contrary to Lorca's assertion that his work is anti-picturesque and anti-folkloric, he serves “the entire Carmen inventory, regardless of whether it is tambourines, knives, castanets, card reading or the cult of virginity”.

But it was precisely this game with the old form and the surrealistic content that also called critics on the scene. On the one hand, there were the avant-garde, who categorically called for a break with the traditional. Luis Buñuel judged:

“Su libro me parece, y parece a las personas que han salido un poco de Sevilla, muy malo. Es una poesía que participa de lo fino y aproximadamente moderno que debe tener cualquier poesía de hoy para que guste a los Andrenios, a los Baezas ya los poetas maricones y cernudos de Sevilla. Pero de ahí a tener nada que ver con los verdaderos, exquisitos y grandes poetas de hoy, existe un abismo. "

“Your book seems very bad to me and to all those who have come out of Seville a little. It is a kind of poetry that participates in the fine and pseudo-modern thing that all poetry of today must have in order to please the Andrenios, the Baezas, the fags and the Cernudos poets of Seville. But that has nothing to do with the real, exquisite and great poets of today; there is an abyss in between. "

The young Salvador Dalí wrote a lewd love letter to Federico García Lorca, which he linked with a slipping of his poetry:

«Tu poesía está ligada de pies y manos a la poesía vieja. Tú quizá creerás atrevidas ciertas imágenes, oounterrarás una dose crecida de irracionalidad en tus cosas, pero yo puedo decirte que tu poesía se mueve dentro de la ilustración de los lugares comunes más estereotipados y más conformistas. (...) Federiquito, en el libro tuyo (...), te he visto a ti, la bestiecita que eres, bestiecita erótica, con tu sexo y tus (...) pequeños ojos de tu cuerpo (...) ) Te quiero por lo que tu libro revela que eres, que es todo al revés de la realidad que los putrefactos han formado de ti (...) Adiós. Creo en tu inspiración, en tu sudor, en tu fatalidad astronómica. »

“Your poetry hangs from head to toe on old poetry. You may think that certain images are daring or find a growing degree of irrationality in your stuff, but I can tell you that your poetry moves in the most stereotypical and conformist platitudes. (…) Federiquito, in your book (…) I saw you, the little beast that you are, little erotic beast, with your gender and your (…) small eyes of your body. (...) I love you for what your book reveals about you, which is quite the opposite of what the rotten have made of you (...) Goodbye. I believe in your inspiration, your sweat, your astronomical fate. "

On the other hand, the traditionalists also took offense. For example, even years after García Lorca's death , Juan Ramón Jiménez accused the Romancero gitano of saying that everything in it was metaphorical pose and rhythmic sculpture, with many borrowings from Schlager.

In 1922 the Concurso de cante jondo , the competition for deep flamenco singing, took place in Granada . It was initiated by Manuel de Falla , and Federico García Lorca himself was heavily involved in it. He was familiar with the poetry of flamenco and had written the cycle Poema de cante jondo himself at the end of 1921 . It is therefore not surprising that, conversely, in flamenco motifs from the Romancero gitano have been and are repeatedly taken up.

References and comments

- ↑ a b Federico Garcia Lorca: Gypsy Romances. Primer romancero gitano . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 978-3-518-22356-7 (Spanish, German, original title: Primer romancero gitano . Translated by Martin von Koppenfels ).

- ^ Frieda H. Blackwell: Deconstructing Narrative. Lorca's Romancero gitano and the Romance sonámbulo . In: Centro Virtual Cervantes (Ed.): Cauce . Literatura. No. 26 , 2003, p. 33 ( cvc.cervantes.es [PDF; accessed on January 28, 2016]).

- ^ Frieda H. Blackwell: Deconstructing Narrative . S. 34 .

- ^ Frieda H. Blackwell: Deconstructing Narrative . S. 35 .

- ^ Frieda H. Blackwell: Deconstructing Narrative . S. 36 .

- ^ A b Frieda H. Blackwell: Deconstructing Narrative . S. 37 .

- ↑ a b Accurate translation. Reproduction of literary translations is waived due to copyright law.

- ^ For example, in Federico García Lorca: Romancero Gitano. In: federicogarcialorca.net. Retrieved January 28, 2020 (Spanish).

- ↑ a b c Pedro Lumbreras García, Sara Lumbreras Sanchón: Introducción . In: Federico Garcia Lorca: Romancero Gitano . Ediciones Akal, Salamanca 2012, ISBN 978-84-460-3535-0 , pp. 34 .

- ↑ a b c d Pedro Lumbreras García, Sara Lumbreras Sanchón: Introducción . S. 35 .

- ^ A b Pedro Lumbreras García, Sara Lumbreras Sanchón: Introducción . S. 36 .

- ^ A b Pedro Lumbreras García, Sara Lumbreras Sanchón: Introducción . S. 37 .

- ^ Pedro Lumbreras García, Sara Lumbreras Sanchón: Introducción . S. 38 .

- ^ Luis Antonio de Villena: La sensibilidad homoerótica en el "Romancero gitano" . In: Los cuadernos de literatura . No. 40 , p. 28–38 (Spanish, cervantes.es [PDF; accessed January 27, 2020]).

- ^ A b Francisco García Lara: Los simbolos en el Romancero gitano . In: Federico García Lorca: Romancero Gitano . eBook. Austral, 2006, ISBN 978-84-670-4504-8 .

- ^ Gustav Siebenmann: Lorca in a sham package. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung. September 2, 2008, accessed January 25, 2020 .

- ↑ Federico García Lorca: Poemas / Gedichte . Reclam, Ditzingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-15-018480-6 (Spanish, German, edited, commented and translated by Gustav Siebenmann).

- ↑ Federico Garcia Lorca: The poems . Ed .: Ernst Rudin, José Manuel López de Abiada. tape I . Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 2008, ISBN 978-3-89244-961-4 , p. 305 (Spanish, German, translated by Enrique Beck ).

- ↑ Martin von Koppenfels: Act of Violence and Transfiguration (epilogue to the volume of poems) . In: Gypsy Romances. Primer romancero gitano . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 978-3-518-22356-7 , pp. 108 .

- ↑ Gustav Siebenmann: To the editions . In: Federico García Lorca: Poemas / Poems . S. 173–174 (edited, commented on and translated by Gustav Siebenmann).

- ↑ a b Martin of Koppenfels: violence and transfiguration . S. 110 .

- ^ Martin von Koppenfels: Act of violence and transfiguration . S. 112 .

- ^ Víctor Fernández: Luis Buñuel: «¡¡Merde !! para su “Platero y yo” ». In: La Razón. May 28, 2018, accessed January 25, 2020 (Spanish).

- ↑ Meant is the poet Luis Cernuda , according to Martin von Koppenfels: Act of violence and transfiguration . S. 109 .

- ^ Martin von Koppenfels: Act of violence and transfiguration . S. 110-111 .

- ^ Antón Castro: La pasión erótica y trágica de Lorca y Dalí. In: Heraldo de Aragón. August 25, 2014, accessed January 25, 2020 (Spanish).

- ^ Gustav Siebenmann: waymarks . In: Federico García Lorca: Poemas / Poems . S. 161 (edited, commented on and translated by Gustav Siebenmann).

- ↑ Juan Vergillos: Lorca y el flamenco . In: El País . October 28, 2016, ISSN 1134-6582 ( elpais.com [accessed January 28, 2020]).