Branded to Kill: Difference between revisions

→Home Video: vhs collection ref |

fix ref link |

||

| Line 263: | Line 263: | ||

| title = The Seijun Suzuki Prepack |

| title = The Seijun Suzuki Prepack |

||

| publisher = Internet Archive |

| publisher = Internet Archive |

||

| year = |

| year = 2002 |

||

| month = April |

| month = April |

||

| url = http://web.archive.org/web/ |

| url = http://web.archive.org/web/20020401060150/http://homevision.com/film.php?id=SUZ010 |

||

| accessdate = 2007-04-05 |

| accessdate = 2007-04-05 |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 01:30, 6 April 2007

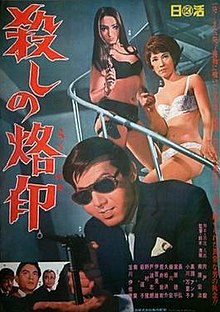

| Branded to Kill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Seijun Suzuki |

| Written by | Hachiro Guryu |

| Produced by | Kaneo Iwai |

| Starring | Joe Shishido Koji Nanbara Annu Mari Mariko Ogawa |

| Cinematography | Kazue Nagatsuka |

| Edited by | Mutsuo Tanji |

| Music by | Naozumi Yamamoto |

| Distributed by | Nikkatsu |

Release dates | |

Running time | 98 min |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Budget | JPY 20 million |

Branded to Kill (殺しの烙印, Koroshi no rakuin) is a 1967 Japanese yakuza film directed by Seijun Suzuki and starring Joe Shishido, Koji Nanbara, Mari Annu and Mariko Ogawa. The story follows the rice-sniffing "Number Three Killer" on a series of jobs. When one goes wrong he finds himself hunted by the enigmatic Number One Killer who may or may not exist.

It was the 40th and final film Suzuki made for the Nikkatsu Company. Studio president Hori Kyusaku notoriously fired him for making "movies that make no sense and no money."[1] Suzuki successfully sued the company for wrongful dismissal but did not direct another feature for 10 years. However, the event made him into a countercultural icon and the film is now considered among his greatest works.

Synopsis

Goro Hanada, the Japanese underworld's third-ranked hitman, and his wife, Mami, return to Tokyo from a trip. They are met at the Haneda Airport by Kasuga, a former hitman turned taxi driver. Kasuga petitions Hanada to assist him break back into the profession, he's lined up a meeting with yakuza boss Michihiko Yabuhara. Hanada agrees and they drive to Yabuhara's club. The two are offered 5 million yen, half in advance, to escort a man from Sagami Beach to Nagano. After the deal is agreed upon Yabuhara covertly seduces Hanada's wife. En route to pick up the client Hanada discovers that Kasuga is an alcoholic and unsuitable for the job. They pick up the client and proceed to their destination. Hanada spots a makeshift roadblock at an underpass, he wakes Kasuga from a drunken stupor and rams the offending car. He then orders Kasuga to watch the client, runs from the car and dispatches a number of gunmen who had staged the ambush. Kasuga panics and flails about in hysterics. Foaming at the mouth he charges an ambusher, Koh, the fourth-ranked hitman, and they kill each other. Hanada leaves the client to get another car but hears three gun shots and rushes back to find the client is safe and three ambushers have been shot cleanly through the forehead. They come upon another ambush near their destination, Hanada kills more gunmen and sets Sakura, the second-ranked hitman, on fire who madly runs towards the car and is shot dead by the client.

Returning home, Hanada's car breaks down in the rain and he meets Misako, a mysterious woman with a deathwish, who offers him a ride. Once home, he has rough sex with his nymphomaniac wife, fueled by his obsession with sniffing boiling rice. Yabuhara hires him to kill four men, the first three are a customs officer, an ocularist and an jewelery dealer. Next, Misako appears at his door and offers him a nearly impossible job to kill a foreigner, which he cannot refuse. During the job a butterfly lands on the barrel of his rifle causing him to miss his target and kill an innocent bystander. Misako tells him that, because of his error, he will lose his rank and be killed. Hanada returns home and makes plans to leave the country but his wife shoots him, sets fire to their apartment and flees. His belt buckle having deflected the bullet, he escapes the building and staggers away. He finds Misako and they go to her apartment. They take alternate turns at he seducing her and them trying to kill each other. She finally succumbs to his advances after he promises to kill her. Afterwards, he finds he cannot kill her as he has fallen in love with her. In a state of confusion, he wanders the streets all night, passing out on the sidewalk. The next day he finds his wife at Yabuhara's club. She tries to seduce him, then faints. He urinates on her. She fakes hysteria and tells him Yabuhara paid her to kill him and that the three men he had been hired to kill stole from Yabuhara's diamond smuggling operation and the fourth was a foreign investigator sent by the supplier. He shoots her twice and she slumps against a toilet, her wig swirling in the water. Hanada gets drunk and waits for Yabuhara to return. When he does, he falls to the ground with a bullet hole in the centre of his forehead.

Hanada returns to Misako's apartment where a film projector has been set up. It displays a nude, bound Misako being tortured with butane torches and the man he had escorted to Nagano tells him that five men will meet him at a pier at 3:00 the next day and kill him. Hanada goes to the pier but kills the men. The man from the film arrives and announces that he is the legendary Number One Killer and will kill Hanada but, in thanks for the work he has done, is only warning him at present. He then gives Hanada a ride back to Misako's apartment. Number One begins to taunt him with threatening phone calls. After a long standoff, Number One comes to the the apartment and announces that he will stay there while deciding how to kill Hanada. They agree to a temporary truce and decide on times to eat, sleep and, later, to link arms everywhere they go, including the toilet. At a restaurant, Number One disappears, leaving a wig swirling in a toilet. Back at the apartment, Hanada finds a note telling him Number One will be waiting for him at Etsuraku Park Gymnasium between 1:00 and 3:00 a.m., and a film depicting a heavily bandaged Misako which tells him he can see her there before he is killed. He decides he can claim Number One's rank and goes to the gymnasium to await his opponent. At 3:00, Number One has not shown and an exhausted Hanada goes to leave. Suddenly, a tape recording comes on explaining, "This is the way Number One works", he exhausts you and then kills you. Hanada puts one of Misako's headbands across his forehead and climbs into a boxing ring. Number One appears and shoots him. Hanada returns a shot, the headband having stopped the bullet. Number One manages a few more shots before dying. Hanada leaps around the ring declaring himself the new Number One Killer when Misako enters the arena on crutches and, crazed, he instinctively shoots her, then falls from the ring.

Production

The film was produced by Kaneo Iwai for the Nikkatsu Company. Shortly before production was scheduled to begin, with a release date already set, it was deemed "inappropriate" by the head office and Suzuki was called in to rewrite the script. Studio president Hori Kyusaku told him he had had to read it twice before he understood it. Suzuki suggested they drop the script but was ordered to proceed.[2] The company was building Joe Shishido into a star and he was assigned to the film. The script was to be rewritten keeping this in mind. It also marks his first nude scene. Suzuki originally wanted Kiwako Taichi, a new talent from the famous theatre troupe Bungakuza, for the female lead but she took a part in another film and the role went to Annu Mari.[1]

It was given a week for pre-production, 25 days to shoot and 3 days for post-production. The budget was approximately 20 million yen. Suzuki did not use storyboards and came up with most ideas either the night before or on the set. He felt that the only person who should know what is going to happen is the director and that inspiration made the picture.[3] One example of his script changes is the addition of the No. 1 Killer's rice-sniffing habit, he explains that he wanted to present a quintessentially "Japanese" killer and boiled rice fit the bill. Suzuki has commended Shishido on his similar drive to make the action scenes as physical and interesting as possible. The film was edited by Mutsuo Tanji in one day. This was made easy by Suzuki's method of shooting only the necessary footage, a habit picked up during his years as an assistant director for Shochiku when film stock was sparse from the war.[1]

Cast

- Joe Shishido as Goro Hanada, the Number Three Killer

- Koji Nambara as the Number One Killer

- Isao Tamagawa as Michihiko Yabuhara

- Annu Mari as Misako Nakajo

- Mariko Ogawa as Mami Hanada, Hanada's wife

- Hiroshi Minami as Gihei Kasuga

Style

Suzuki employed a wide variety of techniques with his singular focus being to make the film as entertaining as possible. It was shot in black and white Nikkatsuscope (2.35:1 aspect ratio). Due to the wide frame, moving a character forward did not produce the dynamic effect he desired so he relied on spotlight use and monochromatic images to compensate in adding "surprise" for the viewer. Conventional framing and film grammar were disregarded in favour spontaneous inspiration. In editing, he frequently abandoned continuity, favouring abstract jumps in time and space as he found it made the film more interesting.[1] Critic David Chute suggested that Suzuki's stylistics had intensified—in seeming congruence with the studio's repeated demands that he rein them in.

"You can see the director reusing specific effects and pointedly cranking them up a notch. In Our Blood Will Not Allow It, the two battling brothers had a heart-to-heart in a car that was enveloped, just for the hell of it, in gorgeous blue moiré patterns of drenching rain. This 'lost at sea' effect is revived in Branded to Kill but there's no sound at all in this version of the scene, except for the gangsters' hushed voices, echoless, plotting some fresh betrayal in a movie-movie isolation chamber."[4]

Conventions are satirized throughout the film. For example, Japanese censorship often involved masking prohibited sections of the screen. Here Suzuki preemptively masked his own compositions but animated them and incorporated them into the film's design.[5]

Reception

At the time of its Japanese theatrical release on June 15, 1967,[6] the film was popular, especially with college audiences, but not financially successful enough to appease Nikkatsu. The company had been criticized for catering to rebellious youths and Suzuki had been drawing studio head Kyusaku Hori's ire for years as his work became increasing anarchic in style.[7] On April 25, 1968, Suzuki received a telephone call from a company secretary informing him that he would not be receiving his salary that month. Two of Suzuki's friends met with Hori the next day and were told that "Suzuki's films were incomprehensible, that they did not make any money and that Suzuki might as well give up his career as a director as he would not be making films for any other companies."[2] A student-run film society, Cine Club, was planning to include the film in a retrospective honouring Suzuki's works but Hori refused them and withdrew all of his films from circulation. With support from the Cine Club, similar student groups, fellow filmmakers and the general public—which included demonstrations—Suzuki sued Nikkatsu for wrongful dismissal. The case lasted three years, during which the circumstances under which the film was made came to light and that he had been made into a scapegoat as the company was in dire financial straits and attempting a mass restructuring. A settlement was reached on December 24, 1971, one million yen, a fraction of his original claim, and a public apology from Hori.[2] The trial and protests had made him into a countercultural icon. The retrospective eventually happened and the film, among others, played at midnight screenings to "packed audiences who wildly applauded."[8] However, Suzuki was blacklisted by the major studios and did not make another feature film until his 1977 A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness.[9]

Branded to Kill reached international audiences through the 1980s and 1990s, featured in various film festivals and retrospectives dedicated wholly or partially to Suzuki,[9][10] followed later in the decade with home video releases. Critics and film enthusiasts regard it as arguably his most unconventional and revered Nikkatsu film.[11] Writer and Flesh Eaters lead singer Chris D. called it a "tour-de-force masterpiece,"[12] a sentiment echoed by fellow musician and film buff John Zorn, who named it a "cinematic masterpiece that transcends its genre."[13] Writer and critic Tony Rayns noted, "Suzuki mocks everything from the clichés of yakuza fiction to the conventions of Japanese censorship in this extraordinary thriller, which rivals Orson Welles' Lady from Shanghai in it's harsh eroticism, not to mention its visual fireworks."[5] Jasper Sharp of the Midnight Eye wrote, "[it] is a bloody marvellous looking film and arguably the pinnacle of the director's strikingly eclectic style."[14]

However, the workings of the plot remain elusive to most. Sharp digressed, "to be honest it isn't the most accessible of films and for those unfamiliar with Suzuki's unorthodox and seemingly disjointed style it will probably take a couple of viewings before the bare bones of the plot begin to emerge."[14] As Zorn has put it, "plot and narrative devices take a back seat to mood, music, and the sensuality of visual images."[13]

Nikkatsu has since embraced the film, which it included in the 2001 retrospective Style to Kill alongside some 20 other of his film. Suzuki appeared at the gala opening with start Annu Mari. This coincided the film's first Japanese DVD release. In 2006, Nikkatsu sponsored the Seijun Suzuki 48 Film Challenge retrospective as part of the Tokyo International Film Festival, showcasing all of his films to date. Suzuki and Mari once again attended.[15] This coincided with the film's Japanese DVD rerelease, this time in the first part of two 6 film box sets.

Legacy

The film has influenced such internationally renowned directors as Jim Jarmusch and Wong Kar Wai.[16] Jarmusch has listed it as his favourite hitman film, alongside Le Samouraï,[17] and thanked Suzuki in the screen credits of his own 1999 hitman film Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai. Most notably, Jarmusch mirrored a scene in which the titular hero kills a target by shooting from a basement up through a sink drain. He went so far as to screen the film for Suzuki when the two met in Tokyo.[18] Branded to Kill is also spoofed in Takeshi Kitano's Getting Any? (1995).

In 2001, Suzuki directed a sequel, Pistol Opera. It loosely continues the original's premise, in which hitmen try to kill each other in competition for the rank of Number One Killer. The character Goro Hanada returns as a mentor figure for the new Number Three, played by Makiko Esumi. However, Hanada is played by Mikijiro Hira in place of Joe Shishido; Suzuki has said that the original intent was for Shishido to play the character again but that the film's producer, Satoru Ogura, wanted Hira instead. The reasons for this remain unclear.[19]

Home Video

Branded to Kill was release in North America by the Criterion Collection on laserdisc,[20] followed by a DVD on February 23, 1999, both containing a 15 minute interview with Suzuki and poster gallery of Shishido films.[21] Home Vision Cinema release a VHS version on June 16, 2000. Both companies conjunctively released Suzuki's Tokyo Drifter in all three formats in addition to a VHS collection packaging the two films together.[22]

A Japanese DVD was released by Nikkatsu on October 26, 2001 in a series linked to the Style to Kill retrospective. They released a new version on October 26, 2006 in a box set with five other Suzuki films.

In the United Kingdom, Second Sight Films released a DVD on February 25, 2002 and a VHS on March 11, 2002.[23] Yume Pictures released a new DVD version on February 26, 2007.[24]

References

- ^ a b c d Suzuki, Seijun (interviewee) (1999). Branded to Kill interview (DVD). The Criterion Collection.

- ^ a b c Ueno, Kohshi. "Suzuki Battles Nikkatsu". The Films of Seijun Suzuki. Pacific Film Archive. pp. p. 8. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Suzuki, Seijun (interviewee) (1999). Tokyo Drifter interview (DVD). The Criterion Collection.

- ^

Chute, David (1994). "Branded to Thrill". Branded to Thrill: The Delirious Cinema of Suzuki Seijun. Institute of Contemporary Arts. pp. pp. 11-17. ISBN 0-905263-44-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) (available online, missing p. 2 for which the text can be found in an earlier version available here) - ^ a b Rayns, Tony (1994). "1967: Branded to Kill". Branded to Thrill: The Delirious Cinema of Suzuki Seijun. Institute of Contemporary Arts. pp. p. 42. ISBN 0-905263-44-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) (available online) - ^ "殺しの烙印" (in Japanese). Japanese Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- ^ Richie, Donald (2005). A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to DVDs and Videos. Kodansha International. pp. p. 108. ISBN 4-77002-995-0.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Willemen, Paul. "The Films of Seijun Suzuki". The Films of Seijun Suzuki. Pacific Film Archive. pp. p. 1. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Rayns, Tony (1994). "Biography". Branded to Thrill: The Delirious Cinema of Suzuki Seijun. Institute of Contemporary Arts. pp. p. 46. ISBN 0-905263-44-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) (available online) - ^ Rayns, Tony. "Branded to Kill". Pacific Film Archive. pp. p. 1. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan. "Branded to Kill Capsule". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ^ D., Chris (2005). "Seijun Suzuki". Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. I.B. Tauris. pp. p. 142. ISBN 1-84511-086-2.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Zorn, John (1999). "Branded to Kill". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ^ a b Sharp, Jasper (2001). "Review: Branded to Kill". Midnight Eye. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|Month=ignored (help) - ^ Brown, Don. "Suzuki Seijun: Still Killing". Japan Film News. Ryuganji.net. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ^ Kurei, Hibiki. "Deep Seijun". Real Tokyo. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ^ Andrew, Geoff (1999). "Jim Jarmusch interviewed by Geoff Andrew (III)". Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wilonsky, Robert (2000). "The Way of Jim Jarmusch". Miami New Times. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mes, Tom (2001). "Review: Pistol Opera". Midnight Eye. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pratt, Doug (1998). "Branded to Kill". DVDLaser.com. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Erickson, Glenn (2002). "Branded to Kill". DVD Talk. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The Seijun Suzuki Prepack". Internet Archive. 2002. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Foster, Dave (2002). "Branded to Kill". DVD Times. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Yume Pictures Announce Seijun Suzuki and Yasuzo Masumura Line-up". JP Review. 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- Criterion Collection essay by John Zorn

- Branded to Kill at IMDb

- Branded to Kill at AllMovie

- Branded to Kill at Rotten Tomatoes

- Template:Ja icon Branded to Kill at the Japanese Movie Database