Golden ratio: Difference between revisions

→Pentagram: copyedit, rm verbose duplication, add figure |

|||

| Line 240: | Line 240: | ||

==== Pentagram ==== |

==== Pentagram ==== |

||

{{details|Pentagram}} |

{{details|Pentagram}} |

||

[[Image:Pentagram-phi.svg|left|thumb|A pentagram colored to distinguish its line segments of different lengths. The four lengths are in [[golden ratio]] to one another.]] |

|||

The golden ratio, φ = (1+√5)/2 ≈ 1.618, satisfying... |

|||

| ⚫ | The golden ratio plays an important role in regular pentagons and pentagrams. Each intersection of edges sections other edges in the golden ratio. Also, the ratio of the length of the shorter segment to the segment bounded by the 2 intersecting edges (a side of the pentagon in the pentagram's center) is φ, as the four-color illustration shows. |

||

:<math>\varphi=1+2\sin(\pi/10)=1+2\sin 18^\circ\,</math> |

|||

:<math>\varphi=1/(2\sin(\pi/10))=1/(2\sin 18^\circ)\,</math> |

|||

:<math>\varphi=2\cos(\pi/5)=2\cos 36^\circ\,</math> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The pentagram includes ten [[isosceles triangle]]s: five [[acute triangle|acute]] and five [[obtuse triangle|obtuse]] isosceles triangles. In all of them, the ratio of the longer side to the shorter side is φ. The acute triangles are [[Golden triangle (mathematics)|golden triangle]]s. The obtuse isosceles triangles are a [[Golden triangle (mathematics)|golden gnomon]]. |

The pentagram includes ten [[isosceles triangle]]s: five [[acute triangle|acute]] and five [[obtuse triangle|obtuse]] isosceles triangles. In all of them, the ratio of the longer side to the shorter side is φ. The acute triangles are [[Golden triangle (mathematics)|golden triangle]]s. The obtuse isosceles triangles are a [[Golden triangle (mathematics)|golden gnomon]]. |

||

Revision as of 22:46, 10 April 2007

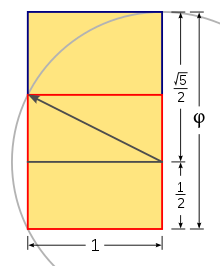

1. Construct a unit square.

2. Draw a line from the midpoint of one side to an opposite corner.

3. Use that line as the radius to draw an arc that defines the long dimension of the rectangle.

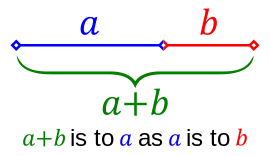

In mathematics and the arts, the ratio between two quantities is the golden ratio if their ratio is equal to the ratio between their sum and the larger of the two. This ratio can be expressed as a mathematical constant, usually denoted ('phi'), which is the following algebraic irrational number with its approximate value:

The figure of a golden section on the right illustrates the defining geometric relationship. Expressed algebraically:

At least since the Renaissance, many artists and architects have proportioned their works to approximate the golden ratio—especially in the form of the golden rectangle, in which the ratio of the longer side to the shorter is the golden ratio—believing this proportion to be aesthetically pleasing. Mathematicians have studied the golden ratio because of its unique and interesting properties.

Other names frequently used for or closely related to the golden ratio are golden section (Latin: sectio aurea), golden mean, golden number, and the Greek letter phi (φ).[1][2][3] Other terms encountered include extreme and mean ratio, medial section, divine proportion (Italian: proporzione divina), divine section (Latin: sectio divina), golden proportion, golden cut,[4] and mean of Phidias.[5][6][7]

Calculation

Two positive numbers a and b are said to be in the golden ratio if

The right equation shows that , which can be substituted in the left part, giving

Canceling b yields

Multiplying both sides by and rearranging terms leads to:

The only positive solution to this quadratic equation is

History

The golden ratio has fascinated intellectuals of diverse interests for at least 2,400 years:

Some of the greatest mathematical minds of all ages, from Pythagoras and Euclid in ancient Greece, through the medieval Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa and the Renaissance astronomer Johannes Kepler, to present-day scientific figures such as Oxford physicist Roger Penrose, have spent endless hours over this simple ratio and its properties. But the fascination with the Golden Ratio is not confined just to mathematicians. Biologists, artists, musicians, historians, architects, psychologists, and even mystics have pondered and debated the basis of its ubiquity and appeal. In fact, it is probably fair to say that the Golden Ratio has inspired thinkers of all disciplines like no other number in the history of mathematics.[1]

Ancient Greek mathematicians first studied what we now call the golden ratio because of its frequent appearance in geometry. The ratio is important in the geometry of regular pentagrams and pentagons. The Greeks usually attributed discovery of the ratio to Pythagoras or to the Pythagoreans, particularly Theodorus or Hippasus.[citation needed] The regular pentagram, which has a regular pentagon inscribed within it, was the Pythagoreans' symbol.

Euclid's Elements (Greek: Στοιχεῖα) gives the first known written definition of the golden ratio: "A straight line is said to have been cut in extreme and mean ratio when, as the whole line is to the greater segment, so is the greater to the less."Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). Euclid explains a construction for cutting (sectioning) a line "in extreme and mean ratio", i.e. the golden ratio.[8] Throughout the Elements, several propositions (theorems in modern terminology) and their proofs employ the golden ratio.[9] Some of these propositions show that the golden ratio is an irrational number. There is no evidence that the Greeks paid more attention to the golden ratio than to other well-studied numbers, such as (pi). [citation needed]

The name "mean and extreme ratio" was the principal term used from the 3rd century BCCite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). until about the 18th century.

The modern history of the golden ratio starts with Luca Pacioli's Divina Proportione of 1509, which captured the imagination of artists, architects, scientists, and mystics with the properties, mathematical and otherwise, of the golden ratio.

Since the twentieth century, the golden ratio has been represented by the Greek letter (phi, after Phidias, a sculptor who is said to have employed it) or less commonly by (tau, the first letter of the ancient Greek root τομή– meaning cut).

Timeline

Reference[10]

- Phidias (490–430 BCE) made the Parthenon statues that seem to embody the golden ratio.

- Plato (427–347 BCE), in his Timaeus, describes five possible regular solids (the Platonic solids, the tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron and icosahedron), some of which are related to the golden ratio.

- Euclid (c. 325–c. 265 BCE), in his Elements, gave the first recorded definition of the golden ratio, which he called, as translated into English, "extreme and mean ratio" (Greek: ακροσκαιμεσοσλογος).Cite error: The

<ref>tag has too many names (see the help page). - Fibonacci (1170–1250) mentioned the numerical series now named after him in his Liber Abaci; the Fibonacci sequence is closely related to the golden ratio.

- Luca Pacioli (1445–1517) defines the golden ratio as the "divine proportion" in his Divina Proportione.

- Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) describes the golden ratio as a "precious jewel": "Geometry has two great treasures: one is the Theorem of Pythagoras, and the other the division of a line into extreme and mean ratio; the first we may compare to a measure of gold, the second we may name a precious jewel."

- Charles Bonnet (1720–1793) points out that in the spiral phyllotaxis of plants going clockwise and counter-clockwise were frequently two successive Fibonacci series.

- Martin Ohm (1792–1872) is believed to be the first to formally use the words "golden ratio" to describe this ratio.

- Edouard Lucas (1842–1891) gives the numerical sequence now known as the Fibonacci sequence its present name.

- Mark Barr (20th century) assigns the first letter of the Greek name Phidias to the golden ratio.

- Roger Penrose (b.1931) discovered a symmetrical pattern that uses the golden ratio in the field of aperiodic tilings, which led to new discoveries about quasicrystals.

Aesthetics

Beginning in the Renaissance, a body of literature on the aesthetics of the golden ratio has developed. As a result, architects, artists, book designers, and others have been encouraged to use the golden ratio in the dimensional relationships of their works.

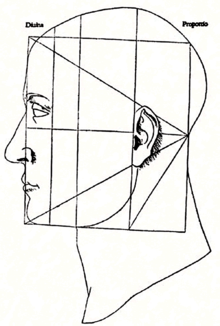

The first and most influential of these was De Divina Proportione by Luca Pacioli, a three-volume work published in 1509. Pacioli, a Franciscan friar, was known mostly as a mathematician, but he was also trained and keenly interested in art. De Divina Proportione explored the mathematics of the golden ratio and advocated its application to yield pleasing, harmonious proportions. Pacioli also saw Catholic religious significance in the ratio, which led to his work's title. Containing illustrations of regular solids by Leonardo Da Vinci, Pacioli's longtime friend and collaborator, De Divina Proportione was a major influence on generations of artists and architects. Da Vinci himself maintained that the human body has proportions that approximate the golden ratio.[citation needed]

The ratio is sometimes used in modern human-made constructions, such as stairs and buildings, and woodwork.

Architecture

Some studies of the Acropolis, including the Parthenon, conclude that many of its proportions approximate the golden ratio. The Parthenon's facade as well as elements of its facade and elsewhere can be circumscribed by golden rectangles.[11] To the extent that classical buildings or their elements are proportioned according to the golden ratio, this might indicate that their architects were aware of the golden ratio and consciously employed it in their designs. Alternatively, it is possible that the architects used their own sense of good proportion, and that this led to some proportions that closely approximate the golden ratio. On the other hand, such retrospective analyses can always be questioned on the ground that the investigator chooses the points from which measurements are made or where to superimpose golden rectangles, and that these choices affect the proportions observed.

Some scholars deny that the Greeks had any aesthetic association with golden ratio. For example, Midhat J. Gazalé says, "It was not until Euclid, however, that the golden ratio's mathematical properties were studied. In the Elements (308 B.C.) the Greek mathematician merely regarded that number as an interesting irrational number, in connection with the middle and extreme ratios. Its occurrence in regular pentagons and decagons was duly observed, as well as in the dodecahedron (a regular polyhedron whose twelve faces are regular pentagons). It is indeed exemplary that the great Euclid, contrary to generations of mystics who followed, would soberly treat that number for what it is, without attaching to it other than its factual properties."[12] And Keith Devlin says, "Certainly, the oft repeated assertion that the Parthenon in Athens is based on the golden ratio is not supported by actual measurements. In fact, the entire story about the Greeks and golden ratio seems to be without foundation. The one thing we know for sure is that Euclid, in his famous textbook Elements, written around 300 B.C., showed how to calculate its value."[13]

A geometrical analysis of the Great Mosque of Kairouan reveals a consistent application of the golden ratio throughout the design, according to Boussora and Mazouz.[14] It is found in the overall proportion of the plan and in the dimensioning of the prayer space, the court, and the minaret. Boussora and Mazouz also examined earlier archaeological theories about the mosque, and demonstrate the geometric constructions based on the golden ratio by applying these constructions to the plan of the mosque to test their hypothesis.

The Swiss architect called Le Corbusier was famous for his contributions to the modern international style. Systems of harmony and proportion were at the centre of his design philosophy. Le Corbusier's faith in the mathematical order of the universe was closely bound to the golden ratio and the Fibonacci series, which he described as "rhythms apparent to the eye and clear in their relations with one another. And these rhythms are at the very root of human activities. They resound in man by an organic inevitability, the same fine inevitability which causes the tracing out of the Golden Section by children, old men, savages and the learned."[15]

Le Corbusier explicitly used the golden ratio in his Modulor system for the scale of architectural proportion. He saw this system as a continuation of the long tradition of Vitruvius, Leonardo da Vinci's "Vitruvian Man", the work of Leon Battista Alberti, and others who used the proportions of the human body to improve the appearance and function of architecture. In addition to the golden ratio, Le Corbusier based the system on human measurements, Fibonacci numbers, and the double unit. He took Leonardo's suggestion of the golden ratio in human proportions to an extreme: he sectioned his model human body's height at the navel with the two sections in golden ratio, then subdivided those sections in golden ratio at the knees and throat; he used these golden ratio proportions in the Modulor system. Le Corbusier's 1927 Villa Stein in Garches exemplified the Modulor system's application. The villa's rectangular ground plan, elevation, and inner structure closely approximate golden rectangles.[16]

Swiss architect Mario Botta bases many of his designs on geometric figures. He designed several private houses in Switzerland that are composed of squares and circles, cubes and cylinders. Botta designed a house in Origlio in which the golden ratio is the proportion between the central section and the side sections of the house.[17]

Art

Painting

Leonardo da Vinci's illustrations in De Divina Proportione and his views that some bodily proportions exhibit the golden ratio have led some scholars to speculate that he incorporated the golden ratio in his own paintings. Some suggest that his Mona Lisa, for example, employs the golden ratio in its geometric equivalents. Whether Leonardo proportioned his paintings according to the golden ratio has been the subject of intense debate. The secretive Leonardo seldom disclosed the bases of his art, and retrospective analysis of the proportions in his paintings can never be conclusive.

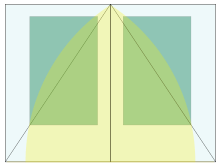

Salvador Dalí explicitly used the golden ratio in his masterpiece, The Sacrament of the Last Supper. The dimensions of the canvas are a golden rectangle. A huge dodecahedron, with edges in golden ratio to one another, is suspended above and behind Jesus and dominates the composition.[18][19]

Mondrian used the golden section extensively in his geometrical paintings.[20]

A statistical study on 565 works of art of different great painters was performed in 1999 and it was found that these artists had not used the golden ratio in the size of their canvases. The study concluded that the average ratio of the two sides of the paintings studied is 1.34, with averages for individual artists ranging from 1.04 (Goya) to 1.46 (Bellini).[21]

Sculpture

Australian sculptor Andrew Rogers's 50-ton stone and gold sculpture, entitled Golden Ratio, is installed outdoors in Jerusalem. Rogers donated the sculpture. The height of each stack of stones, beginning from either end and moving toward the center, is the beginning of the Fibonacci sequence: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8.

Book design

According to Jan Tschichold,[23] "There was a time when deviations from the truly beautiful page proportions 2:3, 1:√3, and the Golden Section were rare. Many books produced between 1550 and 1770 show these proportions exactly, to within half a millimetre."

Perceptual studies

Studies by psychologists, starting with Fechner, have been devised to test the idea that the golden ratio plays a role in human perception of beauty. While Fechner found a preference for rectangle ratios centered on the golden ratio, later attempts to carefully test such a hypothesis have been, at best, inconclusive.[1][24]

Music

James Tenney reconceived his piece For Ann (rising), which consists of up to twelve computer-generated upwardly glissandoing tones (see Shepard tone), as having each tone start so it is the golden ratio (in between an equal tempered minor and major sixth) below the previous tone, so that the combination tones produced by all consecutive tones are a lower or higher pitch already, or soon to be, produced.

Ernő Lendvai analyzes Béla Bartók's works as being based on two opposing systems, that of the golden ratio and the acoustic scale.[25] In Bartok's Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta the xylophone progression occurs at the intervals 1:2:3:5:8:5:3:2:1.[26] French composer Erik Satie used the golden ratio in several of his pieces, including Sonneries de la Rose+Croix. His use of the ratio gave his music an otherworldly symmetry.

The golden ratio is also apparent in the organisation of the sections in the music of Debussy's Image, Reflections in Water, in which the sequence of keys is marked out by the intervals 34, 21, 13 and 8, and the main climax sits at the φ position.[26]

This Binary Universe, an experimental album by Brian Transeau (aka BT), includes a track entitled "1.618" in homage to the golden ratio. The track features musical versions of the ratio and the accompanying video displays various animated versions of the golden mean.

The math metal band Mudvayne have an atmospheric instrumental track called "Golden Ratio" on their first album, L.D. 50. Mathematical concepts are also explored in other songs by Mudvayne.

Nature

Adolf Zeising, whose main interests were mathematics and philosophy, found the golden ratio expressed in the arrangement of branches along the stems of plants, and of veins in leaves. He extended his research to the skeletons of animals and the branchings of their veins and nerves, to the proportions of chemical compounds and the geometry of crystals, as well as the use of proportion in artistic endeavors. In these phenomena he saw the golden ratio operating as a universal law.[27] Zeising wrote in 1854:

[A universal law] in which is contained the ground-principle of all formative striving for beauty and completeness in the realms of both nature and art, and which permeates, as a paramount spiritual ideal, all structures, forms and proportions, whether cosmic or individual, organic or inorganic, acoustic or optical; which finds its fullest realization, however, in the human form.[28]

See also History of aesthetics (pre-20th-century)

Mathematics

Conjugate golden ratio

The negative root of the quadratic equation for φ (the "conjugate root") is . The negative of this quantity corresponds to the length ratio taken in reverse order (shorter segment length over longer segment length, b/a), and is sometimes referred to as the golden ratio conjugate.[1] It is denoted here by the capital Phi ():

Alternatively, can be expressed as

This illustrates the unique property of the golden ratio among positive numbers, that

or its inverse:

Short proofs of irrationality

Recall that we denoted the "larger part" by a and the "smaller part" by b. If the golden ratio is a positive rational number, then it must be expressible as a fraction in lowest terms in the form a / b where a and b are coprime positive integers. The algebraic definition of the golden ratio then indicates that if a / b = , then

Multiplying both sides by ab leads to:

Subtracting ab from both sides and factoring out a gives:

Finally, dividing both sides by b(a-b) yields:

This last equation indicates that a / b could be further reduced to , where a-b is still positive, which is an equivalent fraction with smaller numerator and denominator. But since a / b was already given in lowest terms, this is a contradiction. Thus this number cannot be so written, and is therefore irrational.

Another short proof — perhaps more commonly known — of the irrationality of the golden ratio makes use of the closure of rational numbers under addition and multiplication. If is rational, then is also rational, which is a contradiction if it is already known that the square root of a non-square natural number is irrational.

Alternate forms

The formula can be expanded recursively to obtain a continued fraction for the golden ratio:

and its reciprocal:

The convergents of these continued fractions (1, 2, 3/2, 5/3, 8/5, 13/8, ..., or 1, 1/2, 2/3, 3/5, 5/8, 8/13, ...) are ratios of successive Fibonacci numbers.

The equation likewise produces the continued square root form:

Also:

These correspond to the fact that the length of the diagonal of a regular pentagon is φ times the length of its side, and similar relations in a pentagram.

If x agrees with to n decimal places, then agrees with it to 2n decimal places.

An equation derived in 1994 connects the golden ratio to the Number of the Beast (666):[1]

Which can be combined into the expression:

Ptolemy's theorem

The golden ratio can also be found by applying Ptolemy's theorem to the quadrilateral formed by removing one vertex from a regular pentagon. If the quadrilateral's long edge and diagonals are b, and short edges are a, then Ptolemy's theorem says b2 = a2 + ab which yields

Geometry

The number φ turns up frequently in geometry, particularly in figures with pentagonal symmetry. The length of a regular pentagon's diagonal is φ times its side. The vertices of a regular icosahedron are those of three mutually orthogonal golden rectangles.

There is no known general algorithm to arrange a given number of nodes evenly on a sphere, for any of several definitions of even distribution (see, for example, Thomson problem). However, a useful approximation results from dividing the sphere into parallel bands of equal area and placing one node in each band at longitudes spaced by a golden section of the circle, i.e. 360°/φ ≅ 222.5°. This approach was used to arrange mirrors on the Starshine 3 satellite.

Pentagram

The golden ratio plays an important role in regular pentagons and pentagrams. Each intersection of edges sections other edges in the golden ratio. Also, the ratio of the length of the shorter segment to the segment bounded by the 2 intersecting edges (a side of the pentagon in the pentagram's center) is φ, as the four-color illustration shows.

The pentagram includes ten isosceles triangles: five acute and five obtuse isosceles triangles. In all of them, the ratio of the longer side to the shorter side is φ. The acute triangles are golden triangles. The obtuse isosceles triangles are a golden gnomon.

Relationship to Fibonacci sequence

The mathematics of the golden ratio and of the Fibonacci sequence are intimately interconnected.

The explicit expression for the Fibonacci sequence involves the golden ratio:

The golden ratio is the limit of the ratios of successive terms of the Fibonacci sequence (or any Fibonacci-like sequence):

Therefore, if a Fibonacci number is divided by its immediate predecessor in the sequence, the quotient approximates φ; e.g., 987/610 ≈ 1.6180327868852. These approximations are alternately lower and higher than φ, and converge on φ as the Fibonacci numbers increase, and:

Furthermore, the successive powers of φ obey the Fibonacci recurrence:

This identity allows any polynomial in φ to be reduced to a linear expression. For example:

Other interesting properties

The golden ratio has the simplest expression (and slowest convergence) as a continued fraction expansion of any irrational number (see Alternate forms above). It is, for that reason, the most irrational number, the worst case of Lagrange's approximation theorem. This may be the reason angles close to the golden ratio often show up in phyllotaxis (the growth of plants).

The defining quadratic polynomial and the conjugate relationship lead to decimal values that are interesting for having their fractional part in common with φ:

The sequence of powers of φ contains these values 0.618..., 1.0, 1.618..., 2.618...; more generally, any power of φ is equal to the sum of the two immediately preceding powers:

As a result, one can easily decompose any power of φ into a multiple of φ and a constant. The multiple and the constant are always adjacent Fibonacci numbers. This leads to another property of the positive powers of φ:

If , then:

Fn, the nth number in the Fibonacci series, can be computed as:

The golden ratio has interesting properties when used as the base of a numeral system (see Golden ratio base), sometimes dubbed phinary or φ-nary For example, despite φ being irrational, every integer has a terminating representation, but every fraction has a non-terminating representation.

The golden ratio is the fundamental unit of the algebraic number field and is a Pisot-Vijayaraghavan number.

Decimal expansion

Calculation methods

The golden ratio's decimal expansion can be calculated directly from the formula

with √5 ≈ 2.2360679774997896964. The square root of 5 can be calculated with the Babylonian method, starting with an initial estimate such as x1 = 2 and iterating

for n = 1, 2, 3, ..., until the difference between xn and xn−1 becomes zero, to the desired number of digits.

The Babylonian algorithm for √5 is equivalent to Newton's method for solving the equation x2 − 5 = 0. In its more general form, Newton's method can be applied directly to any algebraic equation, including the equation x2 − x − 1 = 0 that defines the golden ratio. This gives an iteration that converges to the golden ratio itself,

for an appropriate initial estimate x1 such as x1 = 1. A slightly faster method is to rewrite the equation as x − 1 − 1/x = 0, in which case the Newton iteration becomes

These iterations all converge quadratically; that is, each step roughly doubles the number of correct digits. The golden ratio is therefore relatively easy to compute with arbitrary precision. The time needed to compute n digits of the golden ratio is proportional to the time needed to divide two n-digit numbers. This is considerably faster than known algorithms for the transcendental numbers π and e.

An easily programmed alternative using only integer arithmetic is to calculate two large consecutive Fibonacci numbers and divide them. The ratio of Fibonacci numbers F25001 and F25000, each over 5000 digits, yields over 10,000 significant digits of the golden ratio.

Decimal expansion to 1,050 places

(sequence A001622 in the OEIS)

1.6180339887 4989484820 4586834365 6381177203 0917980576

2862135448 6227052604 6281890244 9707207204 1893911374

8475408807 5386891752 1266338622 2353693179 3180060766

7263544333 8908659593 9582905638 3226613199 2829026788

0675208766 8925017116 9620703222 1043216269 5486262963

1361443814 9758701220 3408058879 5445474924 6185695364

8644492410 4432077134 4947049565 8467885098 7433944221

2544877066 4780915884 6074998871 2400765217 0575179788

3416625624 9407589069 7040002812 1042762177 1117778053

1531714101 1704666599 1466979873 1761356006 7087480710

1317952368 9427521948 4353056783 0022878569 9782977834

7845878228 9110976250 0302696156 1700250464 3382437764

8610283831 2683303724 2926752631 1653392473 1671112115

8818638513 3162038400 5222165791 2866752946 5490681131

7159934323 5973494985 0904094762 1322298101 7261070596

1164562990 9816290555 2085247903 5240602017 2799747175

3427775927 7862561943 2082750513 1218156285 5122248093

9471234145 1702237358 0577278616 0086883829 5230459264

7878017889 9219902707 7690389532 1968198615 1437803149

9741106926 0886742962 2675756052 3172777520 3536139362

1076738937 6455606060 5921658946 6759551900 4005559089

...

Pyramids

Both Egyptian pyramids and those mathematical regular square pyramids that resemble them can be analyzed with respect to the golden ratio and other ratios.

Mathematical pyramids

A pyramid in which the apothem (slant height along the bisector of a face) is equal to φ times the semi-base (half the base width) is sometimes called a golden pyramid. The isoceles triangle that is the face of such a pyramid can be constructed from the two halves of a diagonally split golden rectangle (of size semi-base by apothem), joining the medium-length edges to make the apothem. The height of this pyramid is times the semi-base; the square of the height is equal to the area of a face, φ times the square of the semi-base. The slope of the face is also .[2]

The medial right triangle of this "golden" pyramid (see diagram), with sides is interesting in its own right, demonstrating via the Pythagorean theorem the relationship or . The angle with tangent corresponds to the angle that the side of the pyramid makes with respect to the ground, 51.827... degrees (51° 49' 38").[29]

A nearly similar pyramid shape, but with rational proportions, is described in the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus (the source of a large part of modern knowledge of ancient Egyptian mathematics), based on the 3:4:5 triangle;[30] the face slope corresponding to the angle with tangent 4/3 is 53.13 degrees (53 degrees and 8 minutes).[3] The slant height or apothem is 5/3 or 1.666... times the semi-base. The Rhind papyrus has another pyramid problem as well, again with rational slope (expressed as run over rise). Egyptian mathematics did not include the notion of irrational numbers,[31] and the rational inverse slope (run/rise, mutliplied by a factor of 7 to convert to their conventional units of palms per cubit) was used in the building of pyramids.[30]

Another mathematical pyramid with proportions almost identical to the "golden" one is the one with perimeter equal to 2π times the height, or h:b = 4:π. This triangle has a face angle of 51.854° (51°51'), very close to the 51.827° of the golden triangle. This pyramid relationship corresponds to the coincidental relationship .

Egyptian pyramids very close in proportion to these mathematical pyramids are known.[4]

Egyptian pyramids

The shapes of Egyptian pyramids include one that is remarkably close to a "golden pyramid". This is the Great Pyramid of Giza (also known as the Pyramid of Cheops or Khufu). Its slope of 51° 52' is extremely close to the "golden" pyramid inclination of 51° 50' and the π-based pyramid inclination of 51° 51'; other pyramids at Giza (Chephren, 52° 20', and Mycerinus, 50° 47')[30] are also quite close. Whether the relationship to the golden ratio in these pyramids is by design or by accident remains a topic of controversy. Several other Egyptian pyramids are very close to the rational 3:4:5 shape.[5]

Michael Rice[32] asserts that principal authorities on the history of Egyptian architecture have argued that the Egyptians were well acquainted with the Golden ratio and that it is part of mathematics of the Pyramids, citing Giedon (1957).[33] He also asserts that some recent historians of science have denied that the Egyptians had any such knowledge, contending rather that its appearance in an Egyptian building is the result of chance.

In 1859, the Pyramidologist John Taylor (1781-1864) asserted that in the Great Pyramid of Giza built around 2600 BC, the golden ratio is represented by the ratio of the length of the face (the slope height), inclined at an angle θ to the ground, to half the length of the side of the square base, equivalent to the secant of the angle θ.[34] The above two lengths were about 186.4 and 115.2 meters respectively. The ratio of these lengths is the golden ratio, accurate to more digits than either of the original measurements.

Howard Vyse, accoding to Matila Ghyka,[35] reported the great pyramid height 148.2 m, and half-base 116.4 m, yielding 1.6189 for the ratio of slant height to half-base, again more accurate than the data variability.

Egyptian mathematics as understood in modern times, according to mathematician and historian Eric Temple Bell, would not have supported the ability to calculate the slant height of the pyramids, or the ratio to the height, except in the case of the 3:4:5 pyramid, since the 3:4:5 triangle was the only right triangle known to the Egyptians, and they did not know the Pythagorean theorem nor any way to reason about irrationals such as π or φ.[36]

Disputed sightings of the golden ratio

Empirical sightings of the golden ratio in numerous natural proportions and artistic proportions are necessarily just approximations, to a wide range of accuracies. For example, historian John Man suggests that Gutenberg's Bible page was "based on the golden section shape," even though its page size is 44.5 cm × 30.7 cm, which is a ratio of 1.45.[37]

Examples of disputed observations of the golden ratio:

- It is sometimes claimed that the number of bees in a beehive divided by the number of drones yields the golden ratio.[38] In reality, the proportion of drones in a beehive varies greatly by beehive, by bee race, by season, and by beehive health status; the ratio is normally much greater than the golden ratio (usually close to 20:1 in healthy colonies). [citation needed]

- Some specific proportions in the bodies of many animals (including humans[39][40]) and parts of the shells of mollusks[3] and cephalopods are often claimed to be in the golden ratio. There is actually a large variation in the real measures of these elements in a specific individual and the proportion in question is often significantly different from the golden ratio.[39] The ratio of successive phalangeal bones of the digits and the metacarpal bone has been said to approximate the golden ratio.[40] The Nautilus shell, whose construction proceeds in a logarithmic spiral, is often cited, usually under the idea that any logarithmic spiral is related to the golden ratio, but sometimes with the claim that each new chamber is proportioned by the golden ratio relative to the previous one.[38]

- The proportions of different plant components (numbers of leaves to branches, diameters of geometrical figures inside flowers) are often claimed to show the golden ratio proportion in several species.[41] In practice, there are significant variations between individuals, seasonal variations, and age variations in these species. While the golden ratio may be found in some proportions in some individuals at particular times in their life cycles, there is no consistent ratio in their proportions. [citation needed]

- The ratio of the dimensions of the Visa® or MasterCard®.

See also

- Aesthetics

- Canons of page construction

- Golden angle

- Golden function

- Golden rectangle

- Golden triangle (mathematics)

- Golden section search

- Phi (letter)

- Logarithmic spiral

- Fibonacci number

- Modulor

- Sacred geometry

- The Roses of Heliogabalus

- Plastic number

- Penrose tiles

- Dynamic symmetry

- Golden ratio base

- Vitruvian man

References and footnotes

- ^ a b c d Livio, Mario (2002). The Golden Ratio: The Story of Phi, The World's Most Astonishing Number. New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0815-5. Cite error: The named reference "livio" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Piotr Sadowski, The Knight on His Quest: Symbolic Patterns of Transition in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Cranbury NJ: Associated University Presses, 1996

- ^ a b Richard A Dunlap, The Golden Ratio and Fibonacci Numbers, World Scientific Publishing, 1997 Cite error: The named reference "dunlap" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Summerson John, Heavenly Mansions: And Other Essays on Architecture (New York: W.W. Norton, 1963) pp.37 . "And the same applies in architecture, to the rectangles representing these and other ratios (e.g. the 'golden cut'). The sole value of these ratios is that they are intellectually fruitful and suggest the rhythms of modular design."

- ^ Jay Hambidge, Dynamic Symmetry: The Greek Vase, New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 1920

- ^ William Lidwell, Kritina Holden, Jill Butler, Universal Principles of Design: A Cross-Disciplinary Reference, Glouchester MA: Rockport Publishers, 2003

- ^ Pacioli, Luca. De divina proportione, Luca Paganinem de Paganinus de Brescia (Antonio Capella) 1509, Venice.

- ^ Euclid, Elements, Book 6, Proposition 30.

- ^ Euclid, Elements, Book 2, Proposition 11; Book 4, Propositions 10–11; Book 13, Propositions 1–6, 8–11, 16–18.

- ^ Hemenway, Priya (2005). Divine Proportion: Phi In Art, Nature, and Science. New York: Sterling. pp. pp. 20–21. ISBN 1-4027-3522-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Van Mersbergen, Audrey M., "Rhetorical Prototypes in Architecture: Measuring the Acropolis", Philosophical Polemic Communication Quarterly, Vol. 46, 1998.

- ^ Midhat J. Gazalé , Gnomon, Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-691-00514-1

- ^ Keith J. Devlin The Math Instinct: Why You're A Mathematical Genius (Along With Lobsters, Birds, Cats, And Dogs) New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 2005, ISBN 1-56025-672-9

- ^ Boussora, Kenza and Mazouz, Said, The Use of the Golden Section in the Great Mosque of Kairouan, Nexus Network Journal, vol. 6 no. 1 (Spring 2004), Available online

- ^ Le Corbusier, The Modulor p. 25, as cited in Padovan, Richard, Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture (1999), p. 316, Taylor and Francis, ISBN 0-419-22780-6

- ^ Le Corbusier, The Modulor, p. 35, as cited in Padovan, Richard, Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture (1999), p. 320. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-419-22780-6: "Both the paintings and the architectural designs make use of the golden section".

- ^ Urwin, Simon. Analysing Architecture (2003) pp. 154-5, ISBN 0-415-30685-X

- ^ Hunt, Carla Herndon and Gilkey, Susan Nicodemus. Teaching Mathematics in the Block pp. 44, 47, ISBN 1-883001-51-X

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Liviowas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Bouleau, Charles, The Painter's Secret Geometry: A Study of Composition in Art (1963) pp.247-8, Harcourt, Brace & World, ISBN 0-87817-259-9

- ^ Olariu, Agata, Golden Section and the Art of Painting Available online

- ^ Ibid. Tschichold, pp.43 Fig 4. "Framework of ideal proportions in a medieval manuscript without multiple columns. Determined by Jan Tschichold 1953. Page proportion 2:3. margin proportions 1:1:2:3, Text area proportioned in the Golden Section. The lower outer corner of the text area is fixed by a diagonal as well."

- ^ Jan Tschichold, The Form of the Book, Hartley & Marks (1991), ISBN 0-88179-116-4.

- ^ The golden ratio and aesthetics, by Mario Livio

- ^ Lendvai, Ernő (1971). Béla Bartók: An Analysis of His Music. London: Kahn and Averill.

- ^ a b Smith, Peter F. The Dynamics of Delight: Architecture and Aesthetics (New York: Routledge, 2003) pp 83, ISBN 0-415-30010-X

- ^ Ibid. Padovan, R. Proportion: Science, Philosophy, Architecture , pp. 305-06

- ^ Zeising, Adolf, Neue Lehre van den Proportionen des meschlischen Körpers, Leipzig, 1854, preface.

- ^ Midhat Gazale, Gnomon: From Pharaohs to Fractals, Princeton Univ. Press, 1999

- ^ a b c Eli Maor, Trigonometric Delights, Princeton Univ. Press, 2000

- ^ Lancelot Hogben, Mathematics for the Million, London: Allen & Unwin, 1942, p. 63., as cited by Dick Teresi, Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science—from the Babylonians to the Maya, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003, p.56

- ^ Rice, Michael, Egypt's Legacy: The Archetypes of Western Civilisation, 3000 to 30 B.C pp. 24 Routledge, 2003, ISBN 0-415-26876-1

- ^ S. Giedon, 1957, The Beginnings of Architecture, The A.W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, 457, as cited in Rice, Michael, Egypt's Legacy: The Archetypes of Western Civilisation, 3000 to 30 B.C pp.24 Routledge, 2003

- ^ Taylor, The Great Pyramid: Why Was It Built and Who Built It?, 1859

- ^ Matila Ghyka The Geometry of Art and Life, New York: Dover, 1977

- ^ Eric Temple Bell, The Development of Mathematics, New York: Dover, 1940, p.40

- ^ Man, John, Gutenberg: How One Man Remade the World with Word (2002) pp. 166-67, Wiley, ISBN 0-471-21823-5. "The half-folio page (30.7 x 44.5 cm) was made up of two rectangles—the whole page and its text area—based on the so called 'golden section', which specifies a crucial relationship between short and long sides, and produces an irrational number, as pi is, but is a ratio of about 5:8 (footnote: The ratio is 0.618.... ad inf commonly rounded to 0.625)"

- ^ a b Ivan Moscovich, Ivan Moscovich Mastermind Collection: The Hinged Square & Other Puzzles, New York: Sterling, 2004

- ^ a b Stephen Pheasant, Bodyspace, London: Taylor & Francis, 1998

- ^ a b Walter van Laack, A Better History Of Our World: Volume 1 The Universe, Aachen: van Laach GmbH, 2001.

- ^ Derek Thomas, Architecture and the Urban Environment: A Vision for the New Age, Oxford: Elsevier, 2002

Further reading

- Doczi, Gyorgy (1994) [1981]. The Power of Limits: Proportional Harmonies in Nature, Art, and Architecture. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-87773-193-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|origmonth=,|accessmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help) - Euclid (David E. Joyce, ed. 1997) [c. 300 BC]. Elements. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) Citations in the text are to this online edition. - Ghyka, Matila. The Geometry of Art and Life (2nd Edition ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23542-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|origmonth=,|accessmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help) - Joseph, George G. Crest of the Peacock. London: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00659-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|origmonth=,|accessmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help) - Plato (360 BCE). "Timaeus" (HTML). The Internet Classics Archive. Retrieved 2006-05-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|coauthors=, and|month=(help)

- Schneider, Michael S. . A Beginner's Guide to Constructing the Universe: The Mathematical Archetypes of Nature, Art, and Science. ISBN 0-06-092671-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|origmonth=,|accessmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help)

- Huntley, H. E. The Divine Proportion: A Study in Mathematical Proportion. Dover. ISBN 0-486-22254-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|origmonth=,|accessmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help)

- Herz-Fischler, Roger. A Mathematical History of the Golden Number. Dover. ISBN 0-486-40007-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|origmonth=,|accessmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help)

- Walser, Hans. The Golden Section. The Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 0-88385-534-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|origmonth=,|accessmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help)

External links

Mathematics

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Golden Ratio". MathWorld.

- Phiculator, Golden Ratio calculator

- The Golden Section: Phi (homepage created by Dr Ron Knott)

- Phi to 20,000 places

- PHI: The Divine Ratio

- Stephen Marquardt's Beauty Mask based on Golden Ratio

- The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences

- The Pentagram & The Golden Ratio - with many problems to consider

- Template:PDFlink

- Fascinating Flat Facts about Phi (Some excellent phi pages by Dr. R Knott)

- Golden Ratio in Geometry

- Dawson Merrill's Fibonacci / Phi internet resource page

- Khan Amore's Commentary on The Divine Proportion (illustrated)

Aesthetics

- Vast bibliography regarding the Golden Section, esp. in the Arts

- The Russian emigrée cubist painter Marie Vorobieff (Marevna) used the golden ratio to lay out paintings.

- George Markowsky, Template:PDFlink

- Marcus Frings, The Golden Section in Architectural Theory critical analysis

- Laputan Logic The Cult of the Golden Ratio "The Golden Ratio, once a pristine jewel of geometrical truth and simplicity, has become a deity for a cult of hyperlinking headnodders whose chief devotional practice seems to be to handwave their way from one disconnected and unexamined falsehood to another."

- Bruce Rawles has a section on the golden ratio and related topics on his Sacred Geometry tutorial page (http://www.intent.com/sg) and numerous links to both mathematical and mystical sites on his links page (http://www.intent.com/bruce/links.html).

- A profusely-illustrated educational article on the Divine Proportion is to be found at hypatia.org. Of special interest is the included pictorial chart of the many Divine Proportions to be found in the mathematically-optimal human body.

![{\displaystyle \varphi =[1;1,1,1,\dots ]=1+{\frac {1}{1+{\frac {1}{1+{\frac {1}{1+\cdots }}}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8453930e38cb4713d9ee29ff652e3e83562d462b)

![{\displaystyle \varphi ^{-1}=[0;1,1,1,\dots ]=0+{\frac {1}{1+{\frac {1}{1+{\frac {1}{1+\cdots }}}}}}\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fcf361da21af040f2dc8a767b2ce0be61e172f3c)

![{\displaystyle 3\varphi ^{3}-5\varphi ^{2}+4=3(\varphi ^{2}+\varphi )-5\varphi ^{2}+4=3[(\varphi +1)+\varphi ]-5(\varphi +1)+4=\varphi +2\approx 3.618\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d37b374db6ae16db7c12202b8c6319b9306fff73)