Siren (mythology)

In Greek mythology, the Sirens (Greek singular: Σειρήν Seirēn; Greek plural: Σειρῆνες Seirēnes) were three dangerous bird-women, portrayed as seductresses, who lived on an island called Sirenum scopuli. In some later, rationalized traditions the literal geography of the "flowery" island of Anthemoessa, or Anthemusa,[1] is fixed: sometimes on Cape Pelorum and at others in the Sirenusian islands near Paestum or in Capreae.[2] All locations were surrounded by cliffs and rocks. Seamen who sailed near were decoyed by the Sirens' enchanting music and voices to shipwreck on the rocky coast. Although they lured mariners, the sirens were not sea deities.

When the Sirens were given a parentage they were considered the daughters of the river god Achelous, fathered upon Terpsichore, Melpomene, Sterope, or Chthon, the Earth, in Euripides' Helen 167, where Helen in her anguish calls upon "Winged maidens, virgins, daughters of the Earth". Roman writers linked the Sirens more closely to the sea, as daughters of Phorcys.[3] Homer says nothing of their origin or names, but gives the number of the Sirens as two [Odyssey, 12:52]. Later writers mention both their names and number; some state that there were three, Peisinoe, Aglaope, and Thelxiepeia (Tzetzes, ad Lycophron 7l2) or Parthenope, Ligeia, and Leucosia (Eustathius, loc. cit.; Strabo v. §246, 252 ; Servius' commentary on Virgil's Georgics iv. 562). Eustathius (Commentaries §1709) states that they were two, Aglaopheme and Thelxiepeia. Their number is variously reported[citation needed] as between two and five, and their individual names as Thelxiepeia/Thelxiope/Thelxinoe, Molpe, Aglaophonos/Aglaope/Aglaopheme, Pisinoe/Peisinoë/Peisithoe, Parthenope, Ligeia, Leucosia, Raidne, and Teles.

Sirens and death

According to Ovid (Metamorphoses V, 551), the Sirens were the companions of young Persephone and were given wings by Demeter[4] to search for Persephone when she was abducted. Their song is continually calling on Persephone. The term "siren song" refers to an appeal that is hard to resist but that, if heeded, will lead to a bad result. Later writers have inferred that the Sirens were anthropophagous (cannibals), based on Circe's description of them "lolling there in their meadow, round them heaps of corpses rotting away, rags of skin shriveling on their bones."[5]

As Jane Ellen Harrison notes, "It is strange and beautiful that Homer should make the Sirens appeal to the spirit, not to the flesh."[6] "For the matter of the siren song is a promise to Odysseus of mantic truths, with a false promise of living to tell them, they sing,

"Once he hears to his heart's content, sails on, a wiser man.

We know all the pains that the Greeks and Trojans once endured

on the spreading plain of Troy when the gods willed it so—

all that comes to pass on the fertile earth, we know it all!"[7]

"They are mantic creatures like the Sphinx with whom they have much in common, knowing both the past and the future," Harrison observed. "Their song takes effect at midday, in a windless calm. The end of that song is death."[8] That the sailors' flesh is rotting away, though, would suggest it has not been eaten. It has been suggested that, with their feathers stolen, their divine nature kept them alive, but unable to provide for their visitors, who starved to death by refusing to leave.[9]

Appearance

Sirens, like harpies, partake of women and of birds, in various ways. In early Greek art sirens were represented as birds with large women's heads, bird feathers and scaly feet and sometimes[citation needed] manes of lions. Later, they were represented as female figures with the legs of birds, with or without wings playing a variety of musical instruments, especially harps. The tenth century Byzantine encyclopedia Suda[10] says that from their chests up Sirens had the form of sparrows, below they were women, or, alternatively, that they were little birds with women's faces. Birds were chosen because of their characteristic, beautiful voices. Later Sirens were sometimes also depicted as beautiful women, whose bodies, not only their voices, are seductive. The fact that in Spanish, French, Italian, Polish, Romanian or Portuguese, the word for mermaid are respectively Sirena, Sirène, Sirena, Syrena, Sirenă and Sereia creates visual confusion, so that sirens are even represented as mermaids. "The sirens, though they sing to mariners, are not sea-maidens," Harrison cautions; "they dwell on an island in a flowery meadow."[11]

The first century Roman historian Pliny the Elder discounted sirens as pure fable, "although Dinon, the father of Clearchus, a celebrated writer, asserts that they exist in India, and that they charm men by their song, and, having first lulled them to sleep, tear them to pieces."[12]

In his Notebooks Leonardo da Vinci wrote of the siren, "The siren sings so sweetly that she lulls the mariners to sleep; then she climbs upon the ships and kills the sleeping mariners."

In 1917, Franz Kafka wrote in The Silence of the Sirens:

Now the Sirens have a still more fatal weapon than their song, namely their silence. And though admittedly such a thing never happened, it is still conceivable that someone might possibly have escaped from their singing; but from their silence certainly never.

The so-called "Siren" of Canosa, a site in Apulia that was part of Magna Graecia, accompanied the deceased among grave goods in a burial and seems to have some psychopomp characteristics, guiding the dead on the after-life journey. The cast terracotta figure bears traces of its original white pigment. The woman bears the feet and the wings and tail of a bird. It is conserved in the National Archaeological Museum of Spain, in Madrid.

Encounters with the Sirens

In Argonautica (4.891-919) Jason had been warned by Chiron that Orpheus would be necessary in his journey. When Orpheus heard their voices, he drew out his lyre and played his music more beautifully than they, drowning out their voices. One of the crew, however, the sharp-eared hero Butes, heard the song and leapt into the sea, but he was caught up and carried safely away by the goddess Aphrodite.

Odysseus was curious as to what the Sirens sounded like, so, on Circe's advice, he had all his sailors plug their ears with beeswax and tie him to the mast. He ordered his men to leave him tied to the mast, no matter how much he would beg. When he heard their beautiful song, he ordered the sailors to untie him but they stuck to their orders (or they couldn't hear him). When they had passed out of earshot, Odysseus demonstrated with his frowns to be released (Odyssey XII, 39).

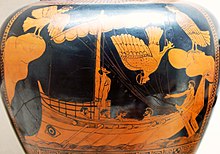

Some post-Homeric authors state that the Sirens were fated to die if someone heard their singing and escaped them, and that after Odysseus passed by they therefore flung themselves into the water and perished.[13] A varying tradition[citation needed] associates this event with their encounter with Jason, though the incident does not appear in Apollonius Rhodius's Argonautica. Many scholars[who?] believe the above vase depicts a drowning attempt on the part of one of the Sirens.

It is also said that Hera, queen of the gods, persuaded the Sirens to enter a singing contest with the Muses. The Muses won the competition and then plucked out all of the Sirens' feathers and made crowns out of them.

In Christian thought

By the fourth century, when pagan beliefs gave way to Christianity, belief in literal sirens was discouraged. Although Jerome, who produced the Latin Vulgate version of the Scriptures, used the word "sirens" to translate Hebrew tenim (jackals) in Isaiah 13:22, and also to translate a word for "owls" in Jeremiah 50:39, this was explained by writers of Church doctrine such as Ambrose to be a mere symbol or allegory for worldly temptations, and not an endorsement of the Greek myth[14].

Sirens continued to be used as a symbol for temptation regularly throughout Christian art of the medieval era; however, in the 17th century, some Jesuit writers began to assert their actual existence, including Cornelius a Lapide, Antonio de Lorea, and Athanasius Kircher, who argued that compartments must have been built for them aboard Noah's Ark[15].

In popular culture

As with many mythological creatures, sirens are directly featured in many artistic works and get passing mentions in many more.

Selected examples

In modern literature, mythological sirens have influenced everything from plant names (for example, a carnivorous plant by the same name in Terry Brooks' Shannara series) to comic book characters (Marvel Comics' superhero Siryn). In television, sirens have appeared in shows ranging from sci-fi (the BBC comedy Red Dwarf episode Psirens) and fantasy (an episode of Charmed titled "Siren Song") to action (the Batman TV series episode 97, featuring The Siren played by Joan Collins) genres. The popularity of siren characters extends to films as well with sirens being the main focus of John Duigan's Sirens (1994) and appearing in the 2000 film O Brother, Where Art Thou? (the latter drawing particularly on the myth of Odysseus and the sirens).

The idea of the lure of the siren also features in the lyrics and composition of many musical pieces such as Erasure's "Siren Song", Roxy Music's album Siren, numerous variations of Song to the Siren, Savatage's song and album Sirens, Nightwish's song and single, 'The Siren' and New Order's album Waiting for the Sirens Call. Due to the bewitching powers suggested by the traditional mythology, sirens also tend to be used as characters in computer and video games such as the Final Fantasy series, the video game series Star Control's species "Syreens" and many others.

Sirens also appeared in the animated film Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas as water, shaped into the bodies of beautiful women. The story retained the sirens' ability to lure sailors to their deaths by song; women were unaffected.

As a classical image the sirens and their story have been reproduced in countless sculptures, engravings and other works of art throughout history, including the paintings by John William Waterhouse which accompany this article. The image remains popular and iconic in a woodcut rendition (reproduced as a logo) representing the global coffee company Starbucks.

See also

- Cecaelia

- Melusine

- Banshee

- Pincoya

- Naiad

- Nix

- Nymph

- Lorelei, an area of the Rhine River where fishermen were drawn to their doom by enchanting songs and music

- Water sprite

- Slavic fairies

- bird-people

- Huldra

- El Trauco

- Syrenka, the Coat of Arms of Warsaw

- Rusalka

- Forbidden Siren (PS2 game)

References

- ^ "We must steer clear of the Sirens, their enchanting song, their meadow starred with flowers" is Robert Fagles' rendering of lines in Odyssey XI.

- ^ Strabo i. p. 22 ; Eustathius of Thessalonica's Homeric commentaries §1709 ; Servius I.e.

- ^ Virgil. V. 846; Ovid XIV, 88.

- ^ Ovid has asked rhetorically "Whence came these feathers and these feet of birds?" "Ovid's aetiology is of course beside the mark," Jane Ellen Harrison observed; the Keres, the Sphinx and even archaic representations of Athena are winged; so is Eos and some Titans in the Gigantomachy reliefs on the Great Altar of Pergamon; Eros is often winged, and the Erotes.

- ^ Odyssey 12.45–6, Fagles' translation.

- ^ Harrison, "The Ker as siren, "'Prolegomenma to the Study of Greek Religion'." (3rd ed. 1922:197-207) p 197.

- ^ Odyssey 12.188–91, Fagles' translation.

- ^ Harrison 199.

- ^ liner notes to Fresh Aire VI by Jim Shey, Classics Department, University of Wisconsin

- ^ Suda on-line

- ^ Harrison 198f.

- ^ Pliny's Natural History 10:70.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 141; Lycophron, Alexandra 712 ff.

- ^ Ambrose, Exposition of the Christian Faith, Bk 3, Chap. 1, 4

- ^ Kircher's account of sirens in Arca Noë, translated in Literature and Lore of the Sea, 1986, Patricia Ann Carlson, p. 270

External links

- Theoi Project, Seirenes the Sirens in classical literature and art

- The Suda (Byzantine Encyclopedia) on the Sirens