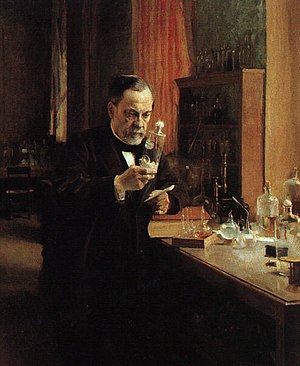

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895), a French chemist and microbiologist, is best known for remarkable breakthroughs in the causes and prevention of disease. His experiments supported the germ theory, also reducing mortality from (child bed fever), and he created the first vaccine for rabies. He was best known to the general public for inventing a method to stop milk and wine from causing sickness; this process came to be called pasteurization. Pasteur is regarded as one of the three main founders of microbiology, together with Ferdinand Cohn and Robert Koch, and he is considered the founder of scientific oenology.[1] He is also credited with dispelling the theory of spontaneous generation with his experiment employing chicken broth and a goose neck flask. He also made many discoveries in the field of chemistry, most notably the asymmetry of crystals.[2] He is buried beneath the Institute Pasteur, an incredibly rare honor in France, where being buried in a cemetery is mandatory save for the fewer than 300 "Great Men" who are entombed in the Pantheon.

early life and biography#REDIRECT louis pasteur

Louis Jean Pasteur was born in Dole in the Jura region of France and grew up in the town of Arbois.[2] There he later had his house and laboratory, which is a Pasteur museum today. His father, Jean Pasteur (1791-1864), was a poorly educated tanner[2] and a decorated Sergeant-Major of the Grande Armee. Louis's aptitude was recognized by his college headmaster, who recommended that the young man apply for the École Normale Supérieure, which accepted him. After serving briefly as professor of physics at Dijon Lycée in 1848, he became professor of chemistry at Strasbourg University,[3] where he met and courted Marie Laurent, daughter of the university's rector in 1849. They were married on 29 May 1849, and together they had five children, only two of whom survived to adulthood. Throughout his life, Louis Pasteur remained an ardent Catholic. A well-known quotation illustrating this is attributed to him: "The more I know, the more nearly is my faith that of the Breton peasant. Could I but know all I would have the faith of a Breton peasant's wife."

Work on chirality and the polarization of light

In Pasteur's early works as a chemist, he resolved a problem concerning the nature of tartaric acid (1849). A solution of this compound derived from living things (specifically, wine lees) rotated the plane of polarization of light passing through it. The mystery was that tartaric acid derived by chemical synthesis had no such effect, even though its chemical reactions were identical and its elemental composition was the same.[2]Upon examination of the minuscule crystals of Sodium ammonium tartrate, Pasteur noticed that the crystals came in two asymmetric forms that were mirror images of one another. Tediously sorting the crystals by hand gave two forms of the compound: solutions of one form rotated polarized light clockwise, while the other form rotated light counterclockwise. An equal mix of the two had no polarizing effect on the light. Pasteur correctly deduced the molecule in question was asymmetric and could exist in two different forms that resemble one another as would left- and right-hand gloves, and that the biological source of the compound provided purely the one type.[4] This was the first time anyone had demonstrated chiral molecules.Pasteur's doctoral thesis on crystallography attracted the attention of M. Puillet and he helped Pasteur garner a position of professor of chemistry at the Faculté (College) of Strasbourg.[3]In 1854 he was named Dean of the new Faculty of Sciences in Lille, and in 1856 he was made administrator and director of scientific studies of the École Normale Supérieure.[3]

Germ theory

Louis demonstrated that the fermentation process is caused by the growth of microorganisms, and that the growth of microorganisms in nutrient broths is not due to spontaneous generation[5] but rather to biogenesis (Omne vivum ex ovo).

He exposed boiled broths to air in vessels that contained a filter to prevent all particles from passing through to the growth medium, and even in vessels with no filter at all, with air being admitted via a long tortuous tube that would not allow dust particles to pass. Nothing grew in the broths; therefore, the living organisms that grew in such broths came from outside, as spores on dust, rather than spontaneously generated within the broth. This was one of the last and most important experiments disproving the theory of spontaneous generation. The experiment also supported germ theory.[5] While Pasteur was not the first to propose germ theory (Girolamo Fracastoro, Agostino Bassi, Friedrich Henle and others had suggested it earlier), he developed it and conducted experiments that clearly indicated its correctness and managed to convince most of Europe it was true.[6] Today he is often regarded as the father of germ theory and bacteriology, together with Robert Koch.[6][7] In a triumphal lecture at the Sorbonne in 1864, Pasteur said, "Never will the doctrine of spontaneous generation recover from the mortal blow struck by this simple experiment," referring to his swan-neck flask experiment wherein he proved that fermenting microorganisms would not form in a flask containing fermentable juice until an entry path was created for them.[4][8][9] Pasteur's research also showed that some microorganisms contaminated fermenting beverages. With this established, he invented a process in which liquids such as milk were heated to kill most bacteria and molds already present within them.[10] He and Claude Bernard completed the first test on April 20 1862. This process was soon afterwards known as pasteurisation (or "pasteurization" in America).[10] Beverage contamination led Pasteur to conclude that microorganisms infected animals and humans as well. He proposed preventing the entry of microorganisms into the human body, leading Joseph Lister to develop antiseptic methods in surgery.[6] In 1865, two parasitic diseases called pébrine and flacherie were killing great numbers of silkworms at Alais (now Alès). Pasteur worked several years proving it was a microbe attacking silkworm eggs which caused the disease, and that eliminating this microbe within silkworm nurseries would eradicate the disease.[11][10] Pasteur also discovered anaerobiosis, whereby some microorganisms can develop and live without air or oxygen, called the Pasteur effect.[12]

Immunology and vaccination

Pasteur's later work on diseases included work on chicken cholera. During this work, a culture of the responsible bacteria had spoiled and failed to induce the disease in some chickens he was infecting with the disease. Upon reusing these healthy chickens, Pasteur discovered that he could not infect them, even with fresh bacteria; the weakened bacteria had caused the chickens to become immune to the disease, even though they had only caused mild symptoms.[13][14] His assistant, Charles Chamberland, had been instructed to inoculate the chickens after Pasteur went on holiday. Chamberland failed to do this, but instead went on holiday himself. On his return, the month old cultures made the chickens unwell, but instead of the infection being fatal, as it usually was, the chickens recovered completely. Chamberland assumed an error had been made, and wanted to discard the apparently faulty culture when Pasteur stopped him. Pasteur guessed the recovered animals now might be immune to the disease, as were the animals at Eure-et-Loir that had recovered from anthrax.[15]In the 1870s he applied this immunisation method to anthrax, which affected cattle, and aroused interest in combating other diseases.

Pasteur publicly claimed he had made the anthrax vaccine by exposing the bacillus to oxygen. His laboratory notebooks, now in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, in fact show Pasteur used the method of rival Jean-Joseph-Henri Toussaint, a Toulouse veterinary surgeon, to create the anthrax vaccine.[16][4] This method used the oxidizing agent potassium dichromate. Pasteur's oxygen method did eventually produce a vaccine but only after he had been awarded a patent on the production of an anthrax vaccine. The notion of a weak form of a disease causing immunity to the virulent version was not new; this had been known for a long time for smallpox. Inoculation with smallpox was known to result in far less scarring, and greatly reduced mortality, in comparison to the naturally acquired disease. Edward Jenner had also discovered vaccination, using cowpox to give cross-immunity to smallpox (in 1796), and by Pasteur's time this had generally replaced the use of actual smallpox material in inoculation. The difference between smallpox vaccination and cholera and anthrax vaccination was that the weakened form of the latter two disease organisms had been generated artificially, and so a naturally weak form of the disease organism did not need to be found.This discovery revolutionized work in infectious diseases, and Pasteur gave these artificially weakened diseases the generic name of vaccines, to honour Jenner's discovery. Pasteur produced the first vaccine for rabies by growing the virus in rabbits, and then weakening it by drying the affected nerve tissue. The rabies vaccine was initially created by Emile Roux, a French doctor and a colleague of Pasteur who had been working with a killed vaccine produced by desiccating the spinal cords of infected rabbits. The vaccine had only been tested on eleven dogs before its first human trial.[4][17]This vaccine was first used on 9-year old Joseph Meister on 6 July 1885, after the boy was badly mauled by a rabid dog.[4] This was done at some personal risk for Pasteur, since he was not a licensed physician and could have faced prosecution for treating the boy, though the boy faced almost certain death from rabies without treatment. After consulting with colleagues, Pasteur decided to go ahead with the treatment, which proved to be a spectacular success, with Meister avoiding the disease. Pasteur was hailed as a hero and the legal matter was not pursued. The treatment's success laid the foundations for the manufacture of many other vaccines. The first of the Pasteur Institutes was also built on the basis of this achievement.[4]Legal risk was not the only kind Pasteur undertook. In The Story of San Michele, Axel Munthe writes of the rabies vaccine research:

Pasteur himself was absolutely fearless. Anxious to secure a sample of saliva straight from the jaws of a rabid dog, I once saw him with the glass tube held between his lips draw a few drops of the deadly saliva from the mouth of a rabid bull-dog, held on the table by two assistants, their hands protected by leather gloves.

Allegations of deception

In 1995, the centennial of the death of Louis Pasteur, the The New York Times ran an article titled "Pasteur's Deceptions". After having thoroughly read Pasteur's lab notes the science historian Gerald L. Geison declared that Pasteur had given a misleading account of the experiment on anthrax vaccine at Pouilly-le-Fort[18].

Honors and final days

Pasteur won the Leeuwenhoek medal, microbiology's highest honor, in 1895.[19] He was a Grand Croix of the Legion of Honor, one of only 75 in all of France. He died in 1895, near Paris, from complications of a series of strokes that had started in 1868.[4] He died while listening to the story of St Vincent de Paul, whom he admired and sought to emulate.[20][21] He was buried in the Cathedral of Notre Dame, but his remains were reinterred in a crypt in the Institut Pasteur, Paris, where he is remembered for his life-saving work.[4]Both the Institut Pasteur and Université Louis Pasteur were named after him.Pasteur was ranked #12 in the 1978 edition of Michael H. Hart's controversial book, The 100: A Ranking Of The Most Influential Persons in History. However, Pasteur was promoted to no. 11, replacing Karl Marx in the 1992 revised edition of the book.[6]

References

- Biographies

- Debré, P. (1998). Louis Pasteur. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5808-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Geison, Gerald L. (1995). The private science of Louis Pasteur. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03442-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Tiner, John Hudson (1990). Louis Pasteur: Founder of Modern Medicine. Fenton, MI: Mott Media. ISBN 0-88062-159-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Influence on medicine and society

- Latour, Bruno (1988). The Pasteurization of France. Boston: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-65761-6.

- Ullmann, Agnes (2007). "Pasteur–Koch: Distinctive Ways of Thinking about Infectious Diseases" (PDF). Microbe. 2 (8). American Society for Microbiology: 383–387. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- Miller, George (1901). A Text-book of Bacteriology. Wood. pp. pp.278-279. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)

- Footnotes

- ^ wine pros.com.Au. Oxford Companion to Wine. "Bordeaux University".

- ^ a b c d Catholic Ency. paragraph 1 Cite error: The named reference "catholic intro" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Catholic Ency. par. 2

- ^ a b c d e f g h David V. Cohn (18 December 2006). "Pasteur". University of Louisville. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

"Fortunately, Pasteur's colleagues Chamberlain [sic] and Roux followed up the results of a research physician Jean-Joseph-Henri Toussaint who reported a year earlier that carbolic-acid/heated anthrax serum would immunize against anthrax. These results were difficult to reproduce and discarded although, as it turned out, Toussaint was on the right track. This led Pasteur and his assistants to substitute an anthrax vaccine prepared not dissimilar to that of Toussaint and different that Pasteur had announced".

- ^ a b Catholic Ency. par. 3

- ^ a b c d Hart, Michael H. (1992). The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History. Citadel Press. pp. pp.60-61. ISBN 0806513500.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Ullmann 383

- ^ Fox, Sidney W. (1972). Molecular Evolution and the Origin of Life. W.H Freeman and Company, San Francisco. pp. pp. 4.171. ISBN 0824766199.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Oparin, Aleksandr I. (1953). Origin of Life. Dover Publications, New York. pp. p.196. ISBN 0486602133.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c Ullmann 384

- ^ Catholic Ency. par. 4

- ^ "The Pasteur Effect". Cornell University. June 10, 2004. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ Catholic Ency. par. 5

- ^ Ullmann 385

- ^ Miller 278-279

- ^ Adrien Loir (1938). Le mouvement sanitaire. pp. 18, 160.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|chapter_title=ignored (|chapter=suggested) (help) - ^ Catholic Ency. par. 6

- ^ See Gerald Geison, The Private Science of Louis Pasteur, Princeton University Press, 1995. ISBN 069101552X.

- ^ Microbe Magazine: Awards: Leeuwenhoek Medal

- ^ Catholic Ency. par. 9

- ^

"Louis Pasteur" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia..

"Louis Pasteur" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia..

External links

- The Institut Pasteur - Foundation Dedicated to the prevention and treatment of diseases through biological research, education and public health activities

- The Pasteur Foundation - A US nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting the mission of the Institut Pasteur in Paris. Full archive of newsletters available online containing examples of US Tributes to Louis Pasteur.

- Pasteur's Papers on the Germ Theory

- The Pasteur Galaxy

- Germ Theory and Its Applications to Medicine and Surgery, 1878

- LIFE magazine's top 100 events of the millennium: Germ theory of disease and Pasteur

- Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) The complete work of Pasteur can be freely downloaded on site of BNF (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Gallica) (click on « Télécharger » (right, at the top)), with specific links:

- Template:Fr icon Template:PDF

- Template:Fr icon Template:PDF

- Template:Fr icon Template:PDF

- Template:Fr icon Template:PDF

- Template:Fr icon Template:PDF

- Template:Fr icon Template:PDF

- Template:Fr icon Template:PDF

Different articles published by Pasteur can be free downloaded on site of BNF (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Gallica) in the differents books of « Comptes rendus de l’Académie des sciences » Comptes rendus de l’Académie des sciences (free downloaded).

- Louis Pasteur

- French biologists

- French microbiologists

- French chemists

- Vaccinologists

- History of medicine

- Alumni of the École Normale Supérieure

- Members of the Académie française

- Humanitarians

- Légion d'honneur recipients

- People from Franche-Comté

- Lille

- French Roman Catholics

- Deaths from stroke

- 1822 births

- 1895 deaths