Effects of climate change

The predicted effects for the environment and for human life are numerous and varied. The main effect is an increasing global average temperature. From this flow a variety of resulting effects, namely, rising sea levels, altered patterns of agriculture, increased extreme weather events, and the expansion of the range of tropical diseases. In some cases, the effects may already be occurring, although it is generally difficult to attribute specific natural phenomena to long-term global warming.

A summary of possible effects and our current understanding can be found in the report of the IPCC Working Group II [1]; a discussion of projected climate changes is found in WG I [2]. The more recent IPCC Fourth Assessment Report outlines the latest agreed international thinking, but omits more controversial ongoing work, particularly in respect of positive feedback mechanisms that might ultimately have the potential to lead to a runaway greenhouse effect.

Proposed responses to the effects of global warming fall into two categories: mitigation and adaptation.

Overview

Projected climate changes due to global warming have the potential to lead to future large-scale and possibly irreversible changes in our climate resulting in impacts at continental and global scales.

Examples of projected climate changes include:

- significant slowing of the ocean circulation that transports warm water to the North Atlantic,

- large reductions in the Greenland and West Antarctic Ice Sheets,

- accelerated global warming due to carbon cycle feedbacks in the terrestrial biosphere, and

- releases of terrestrial carbon from permafrost regions and methane from hydrates in coastal sediments.

The likelihood, magnitude, and timing of many of these changes is uncertain. However, the probability of one or more of these changes occurring is likely to increase with the rate, magnitude, and duration of climate change. Additionally, the US National Academy of Sciences has warned that "greenhouse warming and other human alterations of the earth system may increase the possibility of large, abrupt, and unwelcome regional or global climatic events. ... Future abrupt changes cannot be predicted with confidence, and climate surprises are to be expected." [1]

It is not possible to be certain whether there will be any positive benefits of Global Warming. What is known is that some significant negative impacts are projected and these drive most of the concern about global warming and motivates attempts to mitigate or adapt to the effects of global warming. Almost all scientists agree, however, that the negitive effects would out-weigh the positive effects.

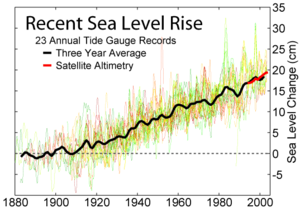

Most of the consequences of global warming would result from one of three physical changes: sea level rise, higher local temperatures, and changes in rainfall patterns (Figure 1). Sea level is generally expected to rise 50-200 cm in the next century (Dean et al. 1987). Such a rise would inundate 7,000 square miles of dry land in the United States (an area the size of Massachusetts) and a similar amount of coastal wetlands; erode recreational beaches 100-200 meters; exacerbate coastal flooding; and increase the salinity of aquifers and estuaries (Titus 1989).

Effects on weather

Increasing temperature is likely to lead to increasing precipitation [3] [4] but the effects on storms are less clear. Extratropical storms partly depend on the temperature gradient, which is predicted to weaken in the northern hemisphere as the polar region warms more than the rest of the hemisphere [5].

More extreme weather

Storm strength leading to extreme weather is increasing, such as the Emanuel (2005) "power dissipation index" of hurricane intensity[6]. Kerry Emmanuel in Nature writes that hurricane power dissipation is highly correlated with temperature, reflecting global warming. Hurricane modeling has produced similar results, finding that hurricanes, simulated under warmer, high-CO2 conditions, are more intense than under present-day conditions. Worldwide, the proportion of hurricanes reaching categories 4 or 5 – with wind speeds above 56 metres per second – has risen from 20% in the 1970s to 35% in the 1990s.[7] Precipitation hitting the US from hurricanes increased by 7% over the twentieth century [8]. See also Time Magazine's "Global Warming: The Culprit?" and [2]. (The extent to which this is due to global warming as opposed to the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation is unclear.)

Increasing extreme weather catastrophes are due to increasing severe weather and an increase in population densities. The World Meteorological Organization[3] and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [4] have linked increasing extreme weather events to global warming, as have Hoyos et al. (2006), writing that the increasing number of category 4 and 5 hurricanes is directly linked to increasing temperatures.[5] NOAA claims that warming induced by greenhouse gas may lead to increasing occurrence of highly destructive category-5 storms.[6]

A substantially higher risk of extreme weather does not necessarily mean a noticeably greater risk of slightly-above-average weather [9]. However, the evidence is clear that severe weather and moderate rainfall are also increasing.

Stephen Mwakifwamba, national co-ordinator of the Centre for Energy, Environment, Science and Technology - which prepared the Tanzanian government's climate change report to the UN - says that change is happening in Tanzania right now. "In the past, we had a drought about every 10 years", he says. "Now we just don't know when they will come. They are more frequent, but then so are floods. The climate is far less predictable. We might have floods in May or droughts every three years. Upland areas, which were never affected by mosquitoes, now are. Water levels are decreasing every day. The rains come at the wrong time for farmers and it is leading to many problems" [10].

Greg Holland, director of the Mesoscale and Microscale Meteorology Division at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, said on April 24, 2006, "The hurricanes we are seeing are indeed a direct result of climate change," and that the wind and warmer water conditions that fuel storms when they form in the Caribbean are, "increasingly due to greenhouse gases. There seems to be no other conclusion you can logically draw." Holland said, "The large bulk of the scientific community say what we are seeing now is linked directly to greenhouse gases." [11] (See also "Global warming?" in tropical cyclone)

Increased evaporation

Over the course of the 20th century, evaporation rates have reduced worldwide [12]; this is thought by many to be explained by global dimming. As the climate grows warmer and the causes of global dimming are reduced, evaporation will increase due to warmer oceans. Because the world is a closed system this will cause heavier rainfall and more erosion, and in more vulnerable tropical areas (especially in Africa), desertification due to deforestation. Many scientists think that it could result in more extreme weather as global warming progresses. The IPCC Third Annual Report says: "...global average water vapour concentration and precipitation are projected to increase during the 21st century. By the second half of the 21st century, it is likely that precipitation will have increased over northern mid- to high latitudes and Antarctica in winter. At low latitudes there are both regional increases and decreases over land areas. Larger year to year variations in precipitation are very likely over most areas where an increase in mean precipitation is projected" [13] [14].

Cost of more extreme weather

Choi and Fisher, writing in Climate Change, vol. 58 (2003) pp. 149, predict that each 1% increase in annual precipitation would enlarge the cost of catastrophic storms by 2.8%.

The Association of British Insurers has stated that limiting carbon emissions would avoid 80% of the projected additional annual cost of tropical cyclones by the 2080s. The cost is also increasing partly because of building in exposed areas such as coasts and floodplains. The ABI claims that reduction of the vulnerability to some inevitable impacts of climate change, for example through more resilient buildings and improved flood defences, could also result in considerable cost-savings in the longterm.[15]

Destabilization of local climates

In the northern hemisphere, the southern part of the Arctic region (home to 4,000,000 people) has experienced a temperature rise 1° to 3 °C over the last 50 years. Canada, Alaska and Russia are experiencing initial melting of permafrost. This may disrupt ecosystems and by increasing bacterial activity in the soil lead to these areas becoming carbon sources instead of carbon sinks [16]. A study (published in Science) of changes to eastern Siberia's permafrost suggests that it is gradually disappearing in the southern regions, leading to the loss of nearly 11% of Siberia's nearly 11,000 lakes since 1971 [17]. At the same time, western Siberia is at the initial stage where melting permafrost is creating new lakes, which will eventually start disappearing as in the east. Western Siberia is the world's largest peat bog, and the melting of its permafrost is likely to lead to the release, over decades, of large quantities of methane—creating an additional source of greenhouse gas emissions [18].

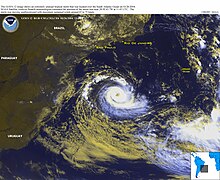

Hurricanes were thought to be an entirely north Atlantic phenomenon. In April 2004, the first Atlantic hurricane to form south of the Equator hit Brazil with 40 m/s (144 km/h) winds; monitoring systems may have to be extended 1,600 km (1000 miles) further south [19].

Oceans

Sea level rise

With increasing average global temperature, the water in the oceans expands in volume, and additional water enters them which had previously been locked up on land in glaciers, for example, the Greenland and the Antarctic ice sheets. An increase of 1.5 to 4.5 °C is estimated to lead to an increase of 15 to 95 cm (IPCC 2001).

The sea level has risen more than 120 metres since the peak of the last ice age about 18,000 years ago. The bulk of that occurred before 6000 years ago. From 3000 years ago to the start of the 19th century, sea level was almost constant, rising at 0.1 to 0.2 mm/yr; since 1900, the level has risen at 1–2 mm/yr [20]; since 1992, satellite altimetry from TOPEX/Poseidon indicates a rate of about 3 mm/yr [21].

The Independent reported in December 2006 that the first island claimed by rising sea levels caused by global warming was Lohachara Island in the Sundarbans in Bay of Bengal. Lohachara was home to 10,000. [22] Earlier reports suggested that it was permanently flooded in the 1980s due to a variety of causes[23], that other islands were also affected and that the population in the Sundarbans had more than tripled to over 4 million.[24]

Temperature rise

The temperature of the Antarctic Southern Ocean rose by 0.17 °C (0.31 °F) between the 1950s and the 1980s, nearly twice the rate for the world's oceans as a whole [25]. As well as effects on ecosystems (e.g. by melting sea ice, affecting algae that grow on its underside), warming could reduce the ocean's ability to absorb CO2.

More important for the United States may be the temperature rise in the Gulf of Mexico. As hurricanes cross the warm Loop Current coming up from South America, they can gain great strength in under a day (as did Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita in 2005), with water above 85 °F seemingly promoting Category 5 storms. Hurricane season ends in November as the waters cool.

Acidification

The world’s oceans soak up much of the carbon dioxide produced by living organisms, either as dissolved gas, or in the skeletons of tiny marine creatures that fall to the bottom to become chalk or limestone. Oceans currently absorb about one metric tonne of CO2 per person per year. It is estimated that the oceans have absorbed around half of all CO2 generated by human activities since 1800 (120,000,000,000 tonnes or 120 petagrams of carbon) [26].

But in water, carbon dioxide becomes a weak carbonic acid, and the increase in the greenhouse gas since the industrial revolution has already lowered the average pH (the laboratory measure of acidity) of seawater by 0.1 units on the 14-point scale, to 8.2. Predicted emissions could lower it by a further 0.5 by 2100, to a level not seen for millions of years.[27]

There are concerns that increasing acidification could have a particularly detrimental effect on corals [28] (16% of the world's coral reefs have died from bleaching since 1998 [29]) and other marine organisms with calcium carbonate shells [30]. Increased acidity may also directly affect the growth and reproduction of fish as well as the plankton on which they rely for food [31].

Shutdown of thermohaline circulation

There is some speculation that global warming could, via a shutdown or slowdown of the thermohaline circulation, trigger localized cooling in the North Atlantic and lead to cooling, or lesser warming, in that region. This would affect in particular areas like Scandinavia and Britain that are warmed by the North Atlantic drift. More significantly, it could lead to an oceanic anoxic event.

The chances of this near-term collapse of the circulation are unclear; there is some evidence for the short-term stability of the Gulf Stream and possible weakening of the North Atlantic drift. There is, however, no evidence for cooling in northern Europe or nearby seas. At this point, temprerature increases are the observations that have been directly made.

Ecosystems

Rising temperatures are beginning to have a noticeable impact on birds. Secondary evidence of global warming — lessened snow cover, rising sea levels, weather changes — provides examples of consequences of global warming that may influence not only human activities but also the ecosystems. Increasing global temperature means that ecosystems will change; some species are being forced out of their habitats (possibly to extinction) because of changing conditions, while others are flourishing.

Few of the terrestrial ecoregions on Earth could expect to be unaffected. Many of the species at risk are arctic fauna such as polar bears, emperor penguins, many salt wetland flora and fauna species, and any species that inhabit the low land areas near the sea. Species that rely on cold weather conditions such as gyrfalcons, and snowy owls that prey on lemmings that use the cold winter to their advantage will be hit hard.

Butterflies have shifted their ranges northward by 200 km in Europe and North America. Plants lag behind, and larger animals' migration is slowed down by cities and highways. In Britain, spring butterflies are appearing an average of 6 days earlier than two decades ago [32]. In the Arctic, the waters of Hudson Bay are ice-free for three weeks longer than they were thirty years ago, affecting polar bears, which do not hunt on land [33].

Two 2002 studies in Nature (vol 421) [34] surveyed the scientific literature to find recent changes in range or seasonal behaviour by plant and animal species. Of species showing recent change, 4 out of 5 shifted their ranges towards the poles or higher altitudes, creating "refugee species". Frogs were breeding, flowers blossoming and birds migrating an average 2.3 days earlier each decade; butterflies, birds and plants moving towards the poles by 6.1 km per decade [35]. A 2005 study concludes human activity is the cause of the temperature rise and resultant changing species behaviour, and links these effects with the predictions of climate models to provide validation for them [36]. Grass has become established in Antarctica for the first time. [37]

Forests in some regions potentially face an increased risk of forest fires. The 10-year average of boreal forest burned in North America, after several decades of around 10,000 km² (2.5 million acres), has increased steadily since 1970 to more than 28,000 km² (7 million acres) annually. [38]. This change may be due in part to changes in forest management practices.

Also note forest fires since 1997 in Indonesia. The fires are started to clear forest for agriculture. These occur from time to time and can set fire to the large peat bogs in that region. The CO2 released by these peat bog fires has been estimated, in an average year, to release 15% of the quantity of CO2 produced by fossil fuel combustion. See BBC article for more details. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/4208564.stm

Ecological productivity

Increasing average temperature and carbon dioxide may have the effect of improving ecosystems' productivity. Atmospheric carbon dioxide is rare in comparison to oxygen (less than 1% of air compared to 21% of air). This carbon dioxide starvation becomes apparent in photorespiration, where there is so little carbon dioxide, that oxygen can enter a plant's chloroplasts and takes the place where carbon dioxide normally would be in the Calvin Cycle. This causes the sugars being made to be destroyed, badly suppressing growth. Satellite data shows that the productivity of the northern hemisphere has increased since 1982 (although attribution of this increase to a specific cause is difficult).

IPCC models predict that higher CO2 concentrations would only spur growth of flora up to a point, because in many regions the limiting factors are water or nutrients, not temperature or CO2; after that, greenhouse effects and warming would continue but there would be no compensatory increase in growth.

Research done by the Swiss Canopy Crane Project suggests that slow-growing trees only are stimulated in growth for a short period under higher CO2 levels, while faster growing plants like liana benefit in the long term. In general, but especially in rain forests, this means that liana become the prevalent species; and because they decompose much faster than trees their carbon content is more quickly returned to the atmosphere. Slow growing trees incorporate atmospheric carbon for decades.

Glacier Retreat

In historic times, glaciers grew during the Little Ice Age, a cool period from about 1550 to 1850. Subsequently, until about 1940, glaciers around the world retreated as climate warmed. Glacier retreat declined and reversed, in many cases, from 1950 to 1980 as a slight global cooling occurred. Since 1980, glacier retreat has become increasingly rapid and ubiquitous, so much so that it has threatened the existence of many of the glaciers of the world. This process has increased markedly since 1995. [39]

Excepting the ice caps and ice sheets of the Arctic and Antarctic, the total surface area of glaciers worldwide has decreased by 50% since the end of the 19th century [40]. Currently glacier retreat rates and mass balance losses have been increasing in the Andes, Alps, Himalaya's, Rocky Mountains and North Cascades. As of March 2005, the snow cap that has covered the top of Mount Kilimanjaro for the past 11,000 years since the last ice age has almost disappeared [41].

The loss of glaciers not only directly causes landslides, flash floods and glacial lake overflow[42], but also increases annual variation in water flows in rivers. Glacier runoff declines in the summer as glaciers decrease in size, this decline is already observable in several regions [43]. Glaciers retain water on mountains in high precipitation years, since the snow cover accumulating on glaciers protects the ice from melting. In warmer and drier years, glaciers offset the lower precipitation amounts with a higher meltwater input [44].

Of particular importance are the Hindu Kush and Himalayan glacial melts that comprise the principal dry-season water source of many of the major rivers of the South, East and Southeast Asian mainland. Increased melting would cause greater flow for several decades, after which "some areas of the most populated regions on Earth are likely to 'run out of water'" as source glaciers are depleted. [45]

The recession of mountain glaciers, notably in Western North America, Franz-Josef Land, Asia, the Alps, Indonesia and Africa, and tropical and sub-tropical regions of South America, has been used to provide qualitative support to the rise in global temperatures since the late 19th century. Many glaciers are being lost to melting further raising concerns about future local water resources in these glacierized areas. The Lewis Glacier, North Cascades pictured at right after melting away in 1990 is one of the 47 North Cascade glaciers observed and all are retreating [46].

Despite their proximity and importance to human populations, the mountain and valley glaciers of temperate latitudes amount to a small fraction of glacial ice on the earth. About 99% is in the great ice sheets of polar and subpolar Antarctica and Greenland. These continuous continental-scale ice sheets, 3 km (1.8 miles) or more in thickness, cap the polar and subpolar land masses. Like rivers flowing from an enormous lake, numerous outlet glaciers transport ice from the margins of the ice sheet to the ocean.

Glacier retreat has been observed in these outlet glaciers, resulting in an increase of the ice flow rate. In Greenland the period since the year 2000 has brought retreat to several very large glaciers that had long been stable. Three glaciers that have been researched, Helheim, Jakobshavns and Kangerdlugssuaq Glaciers, jointly drain more than 16% of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Satellite images and aerial photographs from the 1950s and 1970s show that the front of the glacier had remained in the same place for decades. But in 2001 it began retreating rapidly, retreating 7.2 km (4.5 miles) between 2001 and 2005. It has also accelerated from 20 m (65 ft)/day to 32 m (104 ft)/day.[47] Jakobshavn Isbræ in west Greenland is generally considered the fastest moving glacier in the world. It had been moving continuously at speeds of over 24 m (78 ft)/day with a stable terminus since at least 1950. In 2002, the 12 km (7.5 mile) long floating terminus entered a phase of rapid retreat. The ice front started to break up and the floating terminus disintegrated accelerating to a retreat rate of over 30 m (98 ft)/day. The acceleration rate of retreat of Kangerdlugssuaq Glacier is even larger. Portions of the main trunk that were flowing at 15 m (49 ft)/day in 1988-2001 were flowing at 40 m (131 ft)/day in summer 2005. The front of the glacier has also retreated and has rapidly thinned by more than 100 m (328 ft).[48]

Glacier retreat and acceleration is also apparent on two important outlet glaciers of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Pine Island Glacier, which flows into the Amundsen Sea thinned 3.5 ± 0.9 m (11.5 ± 3 ft) per year and retreated five kilometers (3.1 miles) in 3.8 years. The terminus of the glacier is a floating ice shelf and the point at which it is afloat is retreating 1.2 km/year. This glacier drains a substantial portion of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and has been referred to as the weak underbelly of this ice sheet.[49] This same pattern of thinning is evident on the neighboring Thwaites Glacier.

Further global warming (positive feedback)

Some effects of global warming themselves contribute directly to further global warming.

Methane release from melting permafrost peat bogs

Climate scientists reported in August 2005 that a one million square kilometer region of permafrost peat bogs in western Siberia is starting to melt for the first time since it was formed 11,000 years ago at the end of the last ice age. This will release methane, an extremely effective greenhouse gas, possibly as much as 70,000 million tonnes, over the next few decades. An earlier report in May 2005 reported similar melting in eastern Siberia [50].

This positive feedback was not known about in 2001 when the IPCC issued its last major report on climate change. The discovery of permafrost peat bogs melting in 2005 implies that warming is likely to happen faster than was predicted in 2001.

Methane release from hydrates

Methane clathrate, also called methane hydrate, is a form of water ice that contains a large amount of methane within its crystal structure. Extremely large deposits of methane clathrate have been found under sediments on the ocean floors of Earth. The sudden release of large amounts of natural gas from methane clathrate deposits, in a runaway greenhouse effect, has been hypothesized as a cause of past and possibly future climate changes. The release of this trapped methane is a potential major outcome of a rise in temperature; it is thought that this might increase the global temperature by an additional 5° in itself, as methane is much more powerful as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. The theory also predicts this will greatly affect available oxygen content of the atmophere. This theory has been proposed to explain the most severe mass extinction event on earth known as the Permian-Triassic extinction event.

Carbon cycle feedbacks

There have been predictions, and some evidence, that global warming might cause loss of carbon from terrestrial ecosystems, leading to an increase of atmospheric CO2 levels. Several climate models indicate that global warming through the 21st century could be accelerated by the response of the terrestrial carbon cycle to such warming [51]. All 11 models in the C4MIP study found that a larger fraction of anthropogenic CO2 will stay airborne if climate change is accounted for. By the end of the twenty-first century, this additional CO2 varied between 20 and 200 ppm for the two extreme models, the majority of the models lying between 50 and 100 ppm. The higher CO2 levels led to an additional climate warming ranging between 0.1° and 1.5 °C. However, there was still a large uncertainty on the magnitude of these sensitivities. Eight models attributed most of the changes to the land, while three attributed it to the ocean [52]. The strongest feedbacks in these cases are due to increased respiration of carbon from soils throughout the high latitude boreal forests of the Northern Hemisphere. One model in particular (HadCM3) indicates a secondary carbon cycle feedback due to the loss of much of the Amazon rainforest in response to significantly reduced precipitation over tropical South America [53]. While models disagree on the strength of any terrestrial carbon cycle feedback, they each suggest any such feedback would accelerate global warming.

Observations show that soils in England have been losing carbon at the rate of four million tonnes a year for the past 25 years [54] according to a paper in Nature by Bellamy et al. in September 2005, who note that these results are unlikely to be explained by land use changes. Results such as this rely on a dense sampling network and thus are not available on a global scale. Extrapolating to all of the United Kingdom, they estimate annual losses of 13 million tons per year. This is as much as the annual reductions in carbon dioxide emissions achieved by the UK under the Kyoto Treaty (12.7 million tons of carbon per year).[55]

Forest fires

Rising global temperature might cause forest fires to occur on larger scale, and more regularly. This releases more stored carbon into the atmosphere than the carbon cycle can naturally re-absorb, as well as reducing the overall forest area on the planet, creating a positive feedback loop. Part of that feedback loop is more rapid growth of replacement forests and a northward migration of forests as northern latitudes become more suitable climates for sustaining forests. There is a question of whether the burning of renewable fuels such as forests should be counted as contributing to global warming.

- (Climate Change and Fire)

- (Climate Roulette: Loss of Carbon Sinks & Positive Feedbacks)

- (EPA: Global Warming: Impacts: Forests)

- (Feedback Cycles linking forests, climate and landuse activities)

Retreat of Sea Ice

The sea absorbs heat from the sun, while the ice largely reflects the sun rays back to space. Thus, retreating sea ice will allow the sun to warm the now exposed sea water, contributing to further warming. The mechanism is the same as when a black car heats up faster in sunlight than a white car. This albedo change is also the main reason why IPCC predict polar temperatures to rise up to twice as much as those of the rest of the world.

Negative feedback effects

Following Le Chatelier's principle, the chemical equilibrium of the Earth's carbon cycle will shift in response to anthropogenic CO2 emissions. The primary driver of this is the ocean, which absorbs anthropogenic CO2 via the so-called solubility pump. At present this accounts for only about one third of the current emissions, but ultimately most (~75%) of the CO2 emitted by human activities will dissolve in the ocean over a period of centuries (Archer, 2005; "A better approximation of the lifetime of fossil fuel CO2 for public discussion might be 300 years, plus 25% that lasts forever"). However, the rate at which the ocean will take it up in the future is less certain, and will be affected by stratification induced by warming and, potentially, changes in the ocean's thermohaline circulation.

Also, the thermal radiation of the Earth rises as the temperature to the fourth power.

The impact of these negative feedback effects in relation to the positive feedback effects are part of IPCC's global climate models.

Consequences

See also: Mitigation of global warming

Economic

In commenting overall economic effect of global warming in Copenhagen Consensus, Professor Robert O. Mendelsohn of Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, stated that

- "A series of studies on the impacts of climate change have systematically shown that the older literature overestimated climate damages by failing to allow for adaptation and for climate benefits (see Fankhauser et al 1997; Mendelsohn and Newmann 1999; Tol 1999; Mendelsohn et al 2000; Mendelsohn 2001;Maddison 2001; Tol 2002; Sohngen et al 2002; Pearce 2003; Mendelsohn and Williams 2004). These new studies imply that impacts depend heavily upon initial temperatures (latitude). Countries in the polar region are likely to receive large benefits from warming, countries in the mid-latitudes will at first benefit and only begin to be harmed if temperatures rise above 2.5C (Mendelsohn et al 2000). Only countries in the tropical and subtropical regions are likely to be harmed immediately by warming and be subject to the magnitudes of impacts first thought likely (Mendelsohn et al 2000). Summing these regional impacts across the globe implies that warming benefits and damages will likely offset each other until warming passes 2.5C and even then it will be far smaller on net than originally thought (Mendelsohn and Williams 2004)."[56]

In an October 29 2006, Stern Review by the former Chief Economist and Senior Vice-President of the World Bank Nicholas Stern, he states that climate change could affect growth which could be cut by one-fifth unless drastic action is taken. [57]

Decline of agriculture

For some time it was hoped that a positive effect of global warming would be increased agricultural yields, because of the role of carbon dioxide in photosynthesis, especially in preventing photorespiration, which is responsible for significant destruction of several crops. In Iceland, rising temperatures have made possible the widespread sowing of barley, which was untenable twenty years ago. Some of the warming is due to a local (possibly temporary) effect via ocean currents from the Caribbean, which has also affected fish stocks .[58]

While local benefits may be felt in some regions (such as Siberia), recent evidence is that global yields will be negatively affected. "Rising atmospheric temperatures, longer droughts and side-effects of both, such as higher levels of ground-level ozone gas, are likely to bring about a substantial reduction in crop yields in the coming decades, large-scale experiments have shown" (The Independent, April 27, 2005, "Climate change poses threat to food supply, scientists say" - report on this event).

Moreover, the region likely to be worst affected is Africa, both because its geography makes it particularly vulnerable, and because seventy per cent of the population rely on rain-fed agriculture for their livelihoods. Tanzania's official report on climate change suggests that the areas that usually get two rainfalls in the year will probably get more, and those that get only one rainy season will get far less. The net result is expected to be that 33% less maize—the country's staple crop—will be grown .[59]

Insurance

An industry very directly affected by the risks is the insurance industry; the number of major natural disasters has trebled since the 1960s, and insured losses increased fifteen-fold in real terms (adjusted for inflation).[60] According to one study, 35–40% of the worst catastrophes have been climate change related (ERM, 2002). Over the past three decades, the proportion of the global population affected by weather-related disasters has doubled in linear trend, rising from roughly 2% in 1975 to 4% in 2001 (ERM, 2002).

A June 2004 report by the Association of British Insurers declared "Climate change is not a remote issue for future generations to deal with. It is, in various forms, here already, impacting on insurers' businesses now". It noted that weather risks for households and property were already increasing by 2-4 % per year due to changing weather, and that claims for storm and flood damages in the UK had doubled to over £6 billion over the period 1998–2003, compared to the previous five years. The results are rising insurance premiums, and the risk that in some areas flood insurance will become unaffordable for some.

In the United States, insurance losses have also greatly increased, and according to one study those increases are mostly attributed to increased population and property values in vulnerable coastal areas, though there was also an increase in frequency of weather-related events like heavy rainfalls since the 1950s (Science, 284, 1943-1947).

Transport

Roads, airport runways, railway lines and pipelines, (including oil pipelines, sewers, water mains etc) may require increased maintenance and renewal as they become subject to greater temperature variation, and, in areas with factories and cars. permafrost, subject to subsidence.[61]

Flood defense

For historical reasons to do with trade, many of the world's largest and most prosperous cities are on the coast, and the cost of building better coastal defenses (due to the rising sea level) is likely to be considerable. Some countries will be more affected than others — low-lying countries such as Bangladesh and the Netherlands would be worst hit by any sea level rise, in terms of floods or the cost of preventing them.

In developing countries, the poorest often live on flood plains, because it is the only available space, or fertile agricultural land. These settlements often lack infrastructure such as dykes and early warning systems. Poorer communities also tend to lack the insurance, savings or access to credit needed to recover from disasters.[62]

Migration

Some Pacific Ocean island nations, such as Tuvalu, are concerned about the possibility of an eventual evacuation, as flood defense may become economically inviable for them. Tuvalu already has an ad hoc agreement with New Zealand to allow phased relocation.[63]

In the 1990s a variety of estimates placed the number of environmental refugees at around 25 million. (Environmental refugees are not included in the official definition of refugees, which only includes migrants fleeing persecution.) The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which advises the world’s governments under the auspices of the UN, estimated that 150 million environmental refugees will exist in the year 2050, due mainly to the effects of coastal flooding, shoreline erosion and agricultural disruption (150 million means 1.5% of 2050’s predicted 10 billion world population).[64][65]

Northwest Passage

Melting Arctic ice may open the Northwest Passage in summer, which would cut 5,000 nautical miles (9,000 km) from shipping routes between Europe and Asia. This would be of particular relevance for supertankers which are too big to fit through the Panama Canal and currently have to go around the tip of South America. According to the Canadian Ice Service, the amount of ice in Canada's eastern Arctic Archipelago decreased by 15% between 1969 and 2004.[66]

While the reduction of summer ice in the Arctic may be a boon to shipping, this same phenomenon threatens the Arctic ecosystem, most notably polar bears which depend on ice floes. Subsistence hunters such as the Inuit peoples will find their livelihoods and cultures increasingly threatened as the ecosystem changes due to global warming.

Development

The combined effects of global warming may impact particularly harshly on people and countries without the resources to mitigate those effects. This may slow economic development and poverty reduction, and make it harder to achieve the Millennium Development Goals.[67][68]

In October 2004 the Working Group on Climate Change and Development, a coalition of development and environment NGOs, issued a report Up in Smoke on the effects of climate change on development. This report, and the July 2005 report Africa - Up in Smoke? predicted increased hunger and disease due to decreased rainfall and severe weather events, particularly in Africa. These are likely to have severe impacts on development for those affected.

Environmental

Secondary evidence of global warming — reduced snow cover, rising sea levels, weather changes — provides examples of consequences of global warming that may influence not only human activities but also ecosystems. Increasing global temperature means that ecosystems may change; some species may be forced out of their habitats (possibly to extinction) because of changing conditions, while others may flourish. Few of the terrestrial ecoregions on Earth could expect to be unaffected.

Increasing carbon dioxide may (up to a point) increase ecosystems' productivity; but the interaction with other aspects of climate change, means the environmental impact of this is unclear. An increase in the total amount of biomass produced is not necessarily all good, since biodiversity can still decrease even though a smaller number of species are flourishing.

Water scarcity

Eustatic sea level rises threaten to contaminate groundwater, affecting drinking water and agriculture in coastal zones. Increased evaporation will reduce the effectiveness of reservoirs. Increased extreme weather means more water falls on hardened ground unable to absorb it - leading to flash floods instead of a replenishment of soil moisture or groundwater levels. In some areas, shrinking glaciers threaten the water supply.[69]

Higher temperatures will also increase the demand for water for cooling purposes.

In the Sahel, there has been on average a 25% decrease in annual rainfall over the past 30 years.

Mountains

Mountains cover approximately 25 percent of earth's surface and provide a home to more than one-tenth of global human population. Changes in global climate poses a number of potential risks to mountain habitats. Researchers expect that over time, climate change will affect mountain and lowland ecosystems, the frequency and intensity of forest fires, the diversity of wildlife, and the distribution of water.

Studies suggest that a warmer climate in the United States would cause lower-elevation habitats to expand into the higher alpine zone.[70] Such a shift would encroach on the rare alpine meadows and other high-altitude habitats. High-elevation plants and animals have limited space available for new habitat as they move higher on the mountains in order to adapt to long-term changes in regional climate.

Changes in climate will also affect the depth of the mountains snowpacks and glaciers. Any changes in their seasonal melting can have powerful impacts on areas that rely on freshwater runoff from mountains. Rising temperature may cause snow to melt earlier and faster in the spring and shift the timing and distribution of runoff. These changes could affect the availability of freshwater for natural systems and human uses.[71]

Health

Direct effects of temperature rise

The most direct effect of climate change would be the impacts of hotter temperatures themselves. Extreme high temperatures increase the number of people who die on a given day for many reasons: people with heart problems are vulnerable because one's cardiovascular system must work harder to keep the body cool during hot weather, heat exhaustion, and some respiratory problems increase. Higher air temperature also increase the concentration of ozone at ground level. In the lower atmosphere, ozone is a harmful polluntant. It damages lung tissues and causes problems for people with asthmas other lung diseases. [72]

Rising temperatures have two opposing direct effects on mortality: higher temperatures in winter reduce deaths from cold; higher temperatures in summer increase heat-related deaths.

The distribution of these changes obviously differs. Palutikof et al calculate that in England and Wales for a 1 °C temperature rise the reduced deaths from cold outweigh the increased deaths from heat, resulting in a reduction in annual average mortality of 7000.

The European heat wave of 2003 killed 22,000–35,000 people, based on normal mortality rates (Schär and Jendritzky, 2004). It can be said with 90% confidence that past human influence on climate was responsible for at least half the risk of the 2003 European summer heat-wave (Stott et al 2004).

However, in the United States, only 1000 people die from the cold each year, while twice that number die from the heat.[73] The 2006 United States heat wave has killed 139 people in California as of 29 July 2006. [Deaths of livestock have not been well-documented.] Fresno, in the central California valley, had six consecutive days of 110 degree-plus Fahrenheit temperatures. [74]

Spread of disease

Global warming is expected to extend the favourable zones for vectors conveying infectious disease such as malaria and west nile virus.[75] In poorer countries, this may simply lead to higher incidence of such diseases. In richer countries, where such diseases have been eliminated or kept in check by vaccination, draining swamps and using pesticides, the consequences may be felt more in economic than health terms, if greater spending on preventative measures is required.[76]

Impacts of glacier retreat

The continued retreat of glaciers will have a number of different impacts. In areas that are heavily dependent on water runoff from glaciers that melt during the warmer summer months, a continuation of the current retreat will eventually deplete the glacial ice and substantially reduce or eliminate runoff. A reduction in runoff will affect the ability to irrigate crops and will reduce summer stream flows necessary to keep dams and reservoirs replenished. This situation is particularly acute for irrigation in South America, where numerous artificial lakes are filled almost exclusively by glacial melt.Template:Ref harv Central Asian countries have also been historically dependent on the seasonal glacier melt water for irrigation and drinking supplies. In Norway, the Alps, and the Pacific Northwest of North America, glacier runoff is important for hydropower.

Many species of freshwater and saltwater plants and animals are dependent on glacier-fed waters to ensure a cold water habitat that they have adapted to. Some species of freshwater fish need cold water to survive and to reproduce, and this is especially true with Salmon and Cutthroat trout. Reduced glacier runoff can lead to insufficient stream flow to allow these species to thrive. Ocean krill, a cornerstone species, prefer cold water and are the primary food source for aquatic mammals such as the Blue whale.Template:Ref harv Alterations to the ocean currents, due to increased freshwater inputs from glacier melt, and the potential alterations to thermohaline circulation of the worlds oceans, may impact existing fisheries upon which humans depend as well.

The potential for major sea level rise is mostly dependent on a significant melting of the polar ice caps of Greenland and Antarctica, as this is where the vast majority of glacial ice is located. The British Antarctic Survey has determined from climate modeling that for at least the next 50 years, snowfall on the continent of Antarctica should continue to exceed glacial losses from global warming. The amount of glacial loss on the continent of Antarctica is not increasing significantly, and it is not known if the continent will experience a warming or a cooling trend, although the Antarctic Peninsula has warmed in recent years, causing glacier retreat in that region.Template:Ref harv If all the ice on the polar ice caps were to melt away, the oceans of the world would rise an estimated 70 m (229 ft). However, with little major melt expected in Antarctica, sea level rise of not more than 0.5 m (1.6 ft) is expected through the 21st century, with an average annual rise of 0.0004 m (0.0013 ft) per year. Thermal expansion of the world's oceans will contribute, independent of glacial melt, enough to double those figures.Template:Ref harv

Effects of Global Warming by Country

Effects of global warming on Australia

References

- ^ http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg2/index.htm

- ^ http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/364.htm

- ^ http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/008.htm

- ^ http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/365.htm

- ^ http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/366.htm

- ^ http://www.realclimate.org/index.php?p=181

- ^ http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=dn8002

- ^ http://www.newscientist.com/channel/earth/climate-change/mg18625054.800

- ^ http://www.climateprediction.net/science/pubs/ccs_allen.pdf

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/climatechange/story/0,12374,1517935,00.html

- ^ http://www.cnn.com/2006/TECH/science/04/25/global.warming.hurricanes.reut/index.html

- ^ http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v377/n6551/abs/377687b0.html

- ^ http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/008.htm

- ^ http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/364.htm

- ^ http://www.abi.org.uk/Display/File/Child/552/Financial_Risks_of_Climate_Change.pdf

- ^ http://www.arctic.noaa.gov/essay_romanovsky.html

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/international/story/0,,1503170,00.html

- ^ http://www.newscientist.com/article.ns?id=mg18725124.500

- ^ http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0FQP/is_4688_133/ai_n6157847

- ^ http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/425.htm

- ^ http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/426.htm

- ^ http://news.independent.co.uk/environment/article2099971.ece

- ^ Kolkata Newsline – 22 yrs after deluge, they fear more October 31, 2006

- ^ BBC - Fears rise for sinking Sundarbans 15 September 2003

- ^ http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/295/5558/1275?ijkey=nFvdOLNYlMNZU&keytype=ref&siteid=sci

- ^ http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/305/5682/367/DC1

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/4633681.stm

- ^ http://www.opendemocracy.net/globalization-climate_change_debate/2558.jsp

- ^ http://sun1.rrzn.uni-hannover.de/nhedinst/NATURE_416_389-395_2002.pdf

- ^ http://dsc.discovery.com/news/2006/07/05/acidocean_pla.html

- ^ http://www.opendemocracy.net/debates/article-6-129-2480.jsp

- ^ http://sun1.rrzn.uni-hannover.de/nhedinst/NATURE_416_389-395_2002.pdf

- ^ http://www.lrb.co.uk/v27/n01/byer01_.html

- ^ http://iis-db.stanford.edu/pubs/20115/naturefingerprints.pdf

- ^ http://www.animana.org/tab2/22refugespeciesfeelingtheheat.shtml

- ^ http://iis-db.stanford.edu/pubs/20887/PNAS_5_16_05.pdf

- ^ http://www.heatisonline.org/contentserver/objecthandlers/index.cfm?id=5014&method=full

- ^ http://www.usgcrp.gov/usgcrp/nacc/education/alaska/ak-edu-5.htm

- ^ http://www.nichols.edu/departments/glacier/

- ^ http://www.munichre.com/pages/03/georisks/geo_climate/glaciers/glaciers_en.aspx

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/international/story/0,3604,1437549,00.html

- ^ http://www.rrcap.unep.org/issues/glof/

- ^ http://www.nichols.edu/departments/glacier/glacier.htm

- ^ http://www.munichre.com/pages/03/georisks/geo_climate/glaciers/glaciers_en.aspx

- ^ http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v438/n7066/full/nature04141.html

- ^ http://www.nichols.edu/departments/glacier/

- ^ http://currents.ucsc.edu/05-06/11-14/glacier.asp

- ^ http://www.agu.org/meetings/fm05/fm05-sessions/fm05_C41A.html

- ^ http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/281/5376/549

- ^ http://www.zmag.org/content/showarticle.cfm?SectionID=56&ItemID=8482

- ^ http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v408/n6809/full/408184a0_fs.html

- ^ http://ams.allenpress.com/amsonline/?request=get-document&doi=10.1175%2FJCLI3800.1

- ^ http://education.guardian.co.uk/higher/research/story/0,,965721,00.html

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/life/science/story/0,12996,1565050,00.html

- ^ http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v437/n7056/full/437205a.html

- ^ http://www.copenhagenconsensus.com/Default.aspx?ID=165

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/6096594.stm (Report's stark warning on climate)

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/climatechange/story/0,12374,1517939,00.html

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/climatechange/story/0,12374,1517935,00.html

- ^ http://www.aaisonline.com/communications/Climate%20Change.pdf

- ^ http://www.airportbusiness.com/article/article.jsp?id=2258&siteSection=4

- ^ http://lnweb18.worldbank.org/ESSD/envext.nsf/46ParentDoc/ClimateChange?Opendocument

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/climatechange/story/0,12374,1063181,00.html

- ^ http://www.risingtide.nl/greenpepper/envracism/refugees.html

- ^ http://web.archive.org/web/20050223042051/http://www.risingtide.nl/greenpepper/envracism/refugees.html

- ^ http://www.washingtontimes.com/specialreport/20050612-123835-3711r.htm

- ^ http://www.odi.org.uk/iedg/publications/climate_change_web.pdf

- ^ http://news.independent.co.uk/world/africa/story.jsp?story=648282

- ^ http://www.opendemocracy.net/globalization-climate_change_debate/kazakhstan_2551.jsp

- ^ http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/effects/downloads/potential_effects.pdf

- ^ http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2002/UNEP114.doc.html

- ^ McMichael, A.J., Campbell-Lendrum, D.H., Corvalán, C.F., Ebi, K.L., Githeko, A., Scheraga, J.D. and Woodward, A. 322pp.

- ^ http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/effects/health.html

- ^ http://www.suntimes.com/output/news/cst-nws-heat29.html

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/climatechange/story/0,12374,1517940,00.html

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol6no1/reiter.htm

- Archer, D. (2005). Fate of fossil fuel CO2 in geologic time. J. Geophys. Res., 110, doi:10.1029/2004JC002625.

- Choi, O. and A. Fisher (2003.) "The Impacts of Socioeconomic Development and Climate Change on Severe Weather Catastrophe Losses: Mid-Atlantic Region (MAR) and the U.S." Climate Change 58, 149.

- Emanuel, K.A. (2005) "Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years." Nature 436, pp. 686-688. ftp://texmex.mit.edu/pub/emanuel/PAPERS/NATURE03906.pdf

- ERM (2002). Predicted impact of global climate change on poverty and the sustainable achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. Report prepared for DFID by Environmental Resources Management. Reference 8409. London.

- McMichael et al. (2003). Climate Change and Human Health – Risk and Responses. WHO, UNEP, WMO, Geneva. ISBN 92-4-159081-5.

- Müller, B. (2002) Equity in Climate Change. The Great Divide. Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. Oxford, UK (Executive Summary)

- Knutson, Thomas R. and Robert E. Tuleya (2004). "Impact of CO2-Induced Warming on Simulated Hurricane Intensity and Precipitation:Sensitivity to the Choice of Climate Model and Convective Parameterization". Journal of Climate. 17 (18): 3477–3494.

- J.P. Palutikof, S. Subak and M.D. Agnew. "Impacts of the exceptionally hot weather in the UK", Climate Monitor 25(3)

- Schär and Jendritzky (2004). Hot news from summer 2003. Nature 432: 559-560.

- Stott, et al. (2004). Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature 432, 2 December 2004

- Thomas, C. D., A. Cameron, R. E. Green, M. Bakkenes, L. J. Beaumont, Y. C. Collingham, B. F. N. Erasmus, M. Ferreira de Siqueira, A. Grainger, L. Hannah, L. Hughes, B. Huntley, A. S. Van Jaarsveld, G. E. Midgely, L. Miles, M. A. Ortega-Huerta, A. T. Peterson, O. L. Phillips, and S. E. Williams. 2004. Extinction risk from climate change. Nature 427: 145-148 (and a reply from the authors to some comments).

- Kasting, J. F., Toon, O. B., and Pollack, J.R. (1988). How Climate Evolved on the Terrestrial Planets, Scientific American, 256, p. 90-97.

- An Inconvenient Truth — 2006 film, narrated by Albert Gore, Jr..

See also

External links

- Human Global Warming

- The Impacts of Global Warming and Climate Change from The Nature Conservancy

- Global Warming Information from the Ocean & Climate Change Institute, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

- "Anthropogenic Effects on Tropical Cyclone Activity" (Kerry Emanuel)

- "The Climate of Man", The New Yorker (2005): Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

- Pezza, Alexandre Bernardes and Ian Simmonds (Aug 2005). "The first South Atlantic hurricane: Unprecedented blocking, low shear and climate change". Geophysical Research Letters 32 (L15712).

- Workshop on the Phenomenon Catarina (Brazilian Society of Meteorology)

- American Meteorological Society's Environmental Science Seminar Series (Oct 2005): "Hurricanes: Are They Changing and Are We Adequately Prepared for the Future?"

- Munich Re: World Map of Natural Hazards

- Oliver James, The Guardian, June 30, 2005 Face the facts: For many people climate change is too depressing to think about, and some prefer to simply pretend it doesn't exist

- Mark Lynas, The Guardian, March 31, 2004, "Vanishing worlds"

- The ecological crisis on the verge of a catastrophe by Takis Fotopoulos, (Inclusive Democracy Journal, vol 2, no 4, 11/2006)[7]

- See the impacts of climate change happening now on three Australian ecosystems: 'Tipping Point', Catalyst, ABC-TV

- Peter Schwartz and Doug Randall, Global Business Network, "An Abrupt Climate Change Scenario and Its Implications for United States National Security", A report commissioned by the U.S. Defense Department, October 2003 (executive summary)

- Effects of global warming on skiing

- Stabilisation 2005 conference: survey of scientific papers

- Elevated levels of atmospheric CO2 decrease the nutritional value of plants

- Royal Society, 30 June 2005, "Ocean acidification due to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide"

- Time Magazine's "Global Warming: The Culprit?" (Time Magazine, October 3, 2005, pages 42-46)

- The Evidence Linking Hurricanes and Climate Change: Interview with Judith Curry

- Hurricanes and Global Warming Review of most recent Nature and Science data.

- Recent ice sheet growth in the interior of Greenland

- Increased temperature and salinity in the Nordic Seas

- Effect of global warmng on the Gulf Stream (in French)

- Newest reports on US EPA website

- Glaciers Not On Simple, Upward Trend Of Melting sciencedaily.com, Feb. 21, 2007 "Two of Greenland's largest glaciers (Kangerdlugssuaq and Helheim) shrank dramatically ... between 2004 and 2005. And then, less than two years later, they returned to near their previous rates of discharge."