Ado boundary stone

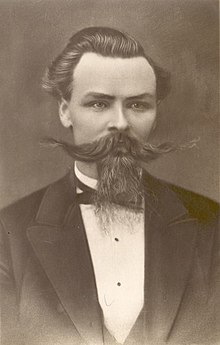

Ado landmark (born January 24 . Jul / 5. February 1849 greg. In the village koksi, then parish Tarvastu / Estonia ; † 20th April 1916 in Menton / France ) was an Estonian poet, political journalist and educator. He also wrote under the pseudonym A. Piirikivi (Estonian translation of the German name Grenzstein).

Life

Ado Grenzstein grew up in very simple circumstances. His father was a farmer and had nine children, including the future painter Tõnis Grenzstein . Grenzstein studied from 1871 to 1874 in the teachers' college of Valga named after Jānis Cimze . From 1874 to 1876 he was employed as a sexton and school teacher in Audru until he found a teaching position in Tartu in 1876 . From 1878 to 1880 he continued his pedagogical training in Vienna . Then he was briefly tutor in Saint Petersburg .

In the age of the national awakening Grenzstein was initially active in the sense of the Estonian national consciousness. He found employment with the Postimees newspaper and criticized the privileges of the Baltic German landowners. Grenzstein founded Olevik ( Present ) newspaper in 1881 , which became one of the most important newspapers in Estonia of the time. The first number of the newspaper appeared in December 1881, from 1882 it came out once a week, from 1905 on twice a week. In the last two years of its publication, 1914 and 1915, even three issues were produced weekly.

In 1888 Grenzstein unexpectedly renounced the Estonian national idea and defended the Russification of the tsarist state power. His magazine Olevik represented increased Russian patriotism, especially in the 1890s. Contrary to the trend among the Estonian population at the time, Grenzstein considered the possibilities of an Estonian national education to be too weak. He saw in Russia the coming strong people of Europe. But he also strongly criticized the German traditions and the German-influenced educated middle class in Estonia.

Grenzstein left Estonia after Grenzstein had fallen out of favor with the Tsarist governor for Estonia because of his own and foreign intrigues, and especially the Estonian publicist and politician Jaan Tõnisson had opposed Grenzstein. From 1901 he lived in Dresden and later moved to Paris . He remained active as a journalist until his death.

Appreciation

Ado Grenzstein is a negative figure in Estonia today because of his advocacy of Russification. The formation of an Estonian nation-state in 1918 has proven his passionate creed for the Estonians to rise into the Russian people to be wrong. The later anti-Semitic and speculative natural philosophy writings completely discredited Grenzstein in the eyes of posterity. Nevertheless he was a man of tremendous creativity and an important part of the Estonian educated elite in the second half of the 19th century. Before 1888 he contributed a lot to the cultural self-confidence of the Estonians and to the renewal and modernization of the Estonian language.

As a poet, he succeeded Koidula with national poetry and was also known for his children's poems. Some of his poems appeared in translation in German-language newspapers of the Tsarist Empire at the end of the 19th century , and later two poems also appeared in German in an anthology of Estonian poetry.

Works (selection)

- 1877: Esimesed luuletused (poems)

- 1877–1880: Saksa keele õpetaja I – III (German textbook)

- 1878: Kooli Laulmise raamat (hymn book)

- 1879: Koolmeistri käsiraamat (teacher's manual)

- 1883: Author of the first Estonian chess book

- 1884: Author of an innovative Estonian dictionary with 1,600 new words

- 1887–1888: Eesti Lugemise-raamat I – II (Estonian reader )

- 1888: Laulud ja salmid (songs and chorales)

- 1894: Eesti küsimus (The Estonian Question)

- 1899: Kauni keele kaitsemiseks (In defense of beautiful language)

- 1899: Mõttesalmid (poems)

- 1899: Herrenkirche or Volkskirche (in German)

- 1910: Ajaloo album (history album)

- 1910: Kodumaa korraldus (The Constitution of the Homeland)

- 1910: Pankrott tulemas (bankruptcy is coming)

- 1911: Tõusikute vastu (Against the insurgents)

- 1912: Juudi küsimus (The Jewish Question)

- 1913: The organization of nature. Natural philosophical considerations with new insights and outlooks (in German)

Literature on the author

- Friedebert Tuglas : Ado Grenzsteini lahkumine. Tartu: Noor-Eesti 1926. 229 pp.

- Jaanus Arukaevu: Ado Grenzsteini tagasitulek. Essee, in: Akadeemia 12/1997, pp. 2467-2514.

- Uus katse hinnata Ado Grenzsteini rolli Eesti ajaloos, in Tuna 2/1999, pp. 111–125.

- Mart Laar : Tuglas , ajalugu ja "Ado Grenzsteini lahkumine", in: Looming 12/1986, pp. 1676–1683.

- Jaan Undusk : "Esimene eesti juudiõgija". Ado Grenzsteini endatapp antisemitism I, II, in: Vikerkaar 2/1991, pp. 66–74; 3/1991, pp. 57-68.

- Anu Pallas: Ado Grenzstein päevalehte püüdmas. Lehekülg XIX sajandi lopu eesti ajakirjandusest, in: Keel ja Kirjandus 5/2018, pp. 382–396.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Eesti kirjanike leksikon. Koostanud Oskar Kruus yes Heino Puhvel. Tallinn: Eesti Raamat 2000, pp. 92-93.

- ↑ Cornelius Hasselblatt : History of Estonian Literature. From the beginning to the present. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter 2006, p. 275.

- ↑ (Estonian) first edition

- ↑ Jaan Undusk: "Esimene eesti juudiõgija". Ado Grenzsteini endatapp antisemitism I, II, in: Vikerkaar 2/1991, pp. 66–74; 3/1991, pp. 57-68.

- ↑ Cornelius Hasselblatt: History of Estonian Literature. From the beginning to the present. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter 2006, p. 302.

- ↑ Cornelius Hasselblatt: Estonian literature in German translation. A reception story from the 19th to the 21st century. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 2011, pp. 89-90; Individual references to: Cornelius Hasselblatt: Estonian literature in German 1784-2003. Bibliography of primary and secondary literature. Bremen: Hempen Verlag 2004, p. 39.

- Jump up ↑ In the Foreign , Sayings , in: Estonian Poems. Translated by W. Nerling. Dorpat: Laakmann 1925, pp. 38-40.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Landmark, Ado |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Piirikivi, A. |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Estonian writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 5, 1849 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kõksi village, then Tarvastu parish , Estonia |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 20, 1916 |

| Place of death | Menton , France |