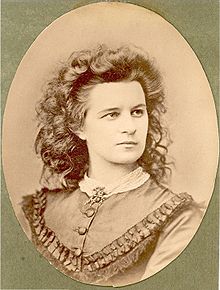

Lydia Koidula

Lydia Koidula (born December 12 . Jul / 24. December 1843 greg. In Vändra , † July 30 jul. / 11. August 1886 greg. In Kronstadt ) was an Estonian poet and playwright.

Life

Her birth name was Lidia Emilie Florentine Jannsen and she was the first child in the marriage of Johann Voldemar Jannsen and Annette Julia Emilie Koch . She first went to school with her father in Vändra and from 1850 in Pärnu . In 1854 she entered the Pärnu girls' high school , where Lilli Suburg was one of her schoolmates.

In 1861 she finished school and then passed the examination for private tutors at the University of Tartu . Instead of working as one, however, she joined her father's editorial team. In 1863 the family moved to Tartu , where her father continued the newspaper Perno Postimees founded in 1857 as Eesti Postimees , and Koidula became the most important designer of this important newspaper for the Estonian national movement alongside her father.

In 1871 she went on a trip to Helsinki with her father and brother Harry , where she met the Finnish writer and journalist Antti Almberg (from 1906 Jalava). They had already been in correspondence and then continued the correspondence intensively. One can assume that Koidula would have liked to marry Almberg, but Almberg did not ask for her hand.

In 1873 she married the Germanized Latvian Eduard Michelson and moved with him to Kronstadt , where her husband had received a position as a military doctor. Their contact with Estonia was not severed as a result, but their participation in Estonian cultural life was inevitably greatly reduced.

In 1876 her husband received a scholarship for a study trip and Koidula took the opportunity to accompany him on this one and a half year trip with her first son, while the four-month-old daughter stayed at home with her grandparents. In this way she toured Wroclaw , Strasbourg , Freiburg and Vienna . Their second daughter was born in the Austrian capital (cf. the novella Viini plika by the Estonian writer Asta Põldmäe ).

In 1880, Koidula briefly took over the management of the newspaper in Tartu again after her father suffered a stroke. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1882 and the last year she could endure only on opium. Lydia Koidula died in 1886 and was buried in Kronstadt. Her ashes only reached Tallinn on the 60th anniversary of her death.

Early work

Her first Estonian works were translations from German, which she had been doing for the newspaper since 1861. Most of them appeared anonymously. In 1864 the first book by Koidula came out, Ojamölder ja temma minnia (The ditch miller and his daughter-in-law). As was customary at the time, it was a translation from German, namely Louis Würdig's Auf der Grabenmühle or Geld und Herz (published in 1858 in the magazine Die Maje ). Since this was not specified, which was also common at the time, the work was received as the original. It was not until 1932 that the Estonian poet and literary scholar Gustav Suits revealed the source and aptly summed up the problem: “So we are witnesses to the following paradoxical phenomenon: The completely marginal role model Auf der Grabenmühle has long been forgotten in its country of origin and is hardly ever read of the developed educated; an imitation for 10 kopecks is unforgotten by any backwoodsmen and is still a school reading today! ”.

Her second book, published in Tartu in 1866, was also an adaptation from German: Perùama wiimne Inka ('The Last Inka of Peru') based on the story Huaskar by WO von Horn . It describes the struggle of the native Peruvians against the Spanish conquerors in the 16th century, and Koidula saw parallels with the Estonians' efforts to emancipate.

Even after that, Koidula published some prose adaptations, but she achieved her greatest impact with her poems and dramas.

Poetry

The approaching author wrote her first poems in German in 1857. That was normal in what was then Estonia, where all secondary education was in German. Koidula's first Estonian poem did not appear until 1865 under the pseudonym "L." in Postimees . To this day, it is one of the most famous poems by Koidula and every Estonian schoolchild. It has also been translated into German several times, including by Carl Hunnius in 1924 :

At the edge of the village

how lovely it was there on the edge of the village,

We children knew him,

Where everything was full of dew grass

Up to our knees;

Where in the glow of the evening fire

In blooming lawns

I played until grandfather's hand brought

his child to rest. -

How gladly to look over a fence

If I were ready for him, -

But he said: "Child, wait, trust -

the time will also come!"

She came, oh - a lot became clear to me,

I saw 'many' sea and land,

All that was not half so dear to me,

When the edge of the village was there.

Afterwards Koidula published poems regularly and in 1866 her first collection of poems, Waino-Lilled (' Field Flowers ') appeared - anonymously - in Kuressaare . Here, too, of the total of 34 poems, only five were original poems, all the others were transcriptions or more free adaptations of German poems, which she had mainly taken from her German reading books at school.

A year later, the second collection of Koidula came out in Tartu, the title Emmajöe öpik (in today's orthography Emajõe ööbik ) for its current nickname: As "Nightingale from Emajõgi ", d. i. the river flowing through Tartu is what the poetess is often called today. There were still German models that Koidula used as a guide for her fatherland poetry. If it for example in August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben was just in Germany, / Because my sweetheart has to live (from the poem only in Germany! ), Koidula wrote an Estonian bride and Estonian groom / only I will praise the poem ( Kaugelt koju tulles (Coming home from afar))

Overall, this collection, which contained 45 poems, was much more independent than the debut collection. Here the love for their homeland, the language of the country and loyalty to it was the theme. The following poem has become very popular:

Are surmani küll tahan

Ma kalliks pidada,

Mo õitsev Eesti rada,

Mo lehkav isamaa!

Mo Eesti vainud, jõed

Ja minu emakeel,

Teid kõrgeks kiita tahan

Ma surmatunnil veel!

(German interlinear translation: I / you will cherish until death / my blossoming Estonian path, / my fragrant fatherland! / My Estonian fields, rivers / and my mother tongue / I want to praise you / in the hour of my death!)

Due to her personal circumstances, Koidula did not publish any further volumes of poetry during her lifetime, but she by no means fell silent. She continued to write, so that her oeuvre grew to over 300 poems. Only a quarter had been published in the two collections of poetry, a further quarter had been scattered in newspapers. Half of it was published after her death.

Stage literature

Koidula's activity for the Estonian theater was groundbreaking, even though she only had four plays in this area, two of which were not even printed and the first was based on a German model. Nevertheless, she became the founder of an independent Estonian theater literature.

In 1865, Koidula's father founded the Vanemuine Society in Tartu as a men's choir. When they wanted to celebrate their fifth anniversary in 1870, Koidula had the idea of doing this with a play. To do this, she translated Theodor Körner's Der Vetter from Bremen , transferred it to an Estonian environment and called the text Saaremaa Onupoeg ('The Vetter from Saaremaa.'). The piece was performed three times and received positively, so that Koidula felt encouraged to continue.

In autumn 1870 her second piece Maret ja Miina ehk Kosjakased ('Maret und Miina or Die Freiersbirken') was finished, which was also performed three times successfully. It was based on a German prose presentation by Horn.

With her third piece, Särane mulk, ehk Sada wakka tangusoola , Koidula succeeded in completely breaking away from foreign models . 'Mulk' is a joking and pejorative term for a resident of southwest Estonia, the title of the piece translates as 'So a mulk or a hundred bushels of salt'. The comedy is about the usual contrast between love and (supposed) marriage of convenience. In the end, however, the father, who wanted to marry his daughter against her will, has to realize that his preferred candidate was a cheat, and everything turns out for the better. The father could have noticed this earlier if he had read the newspaper more carefully. A key message of the play is that education (here in the form of reading the newspaper) is the highest good - also in matters of love.

Koidula wrote the last play in 1880 during her time in Kronstadt. Kosjaviinad ehk kuidas Tapiku pere laulupidule sai ('The free schnapps or How the Tapiku family got to the song festival') was not performed and was only printed and performed after the Second World War. Originally it was a commission for the third song festival (1880).

Reception and aftermath

In Estonia

Despite the relatively few book publications during his lifetime, Koidula's poems quickly became known and popular because they were repeatedly reprinted in school books. The popular school books by Carl Robert Jakobson play a decisive role here . It was also he who suggested the poet name Koidula , based on the Estonian word koit , which means 'dawn'.

In addition to Jakobson, Koidula also had intensive contact with Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald , the author of the Estonian national epic Kalevipoeg . In their correspondence, some of which are still in German, they discussed the possibilities of Estonian poetry.

Koidula's portrait was depicted on the Estonian 100 kroner banknote from 1992 to 2010 , which was valid until the introduction of the Euro in 2011. It shows part of a poem in her handwriting.

The Estonian writer Mati Unt wrote the play Vaimude tund Jannseni tänaval (' Witching Hour in Jannsenstrasse') in 1984 , in which he had Lydia Koidula and her Finnish biographies Aino Kallas , who never met each other, appear together.

Many of Koidula's poems are set to music and are now part of the well-known song repertoir of Estonians. During the Soviet era, when the Estonian national anthem was banned, a poem by Gustav Ernesaks by Koidula, Mu isamaa on minu arm ('My fatherland is my love'), became the “secret” national anthem.

In Germany

In Germany, the orientalist and Finnougrist Wilhelm Schott was one of the first to make Koidula known. He mentioned her for the first time in 1868 in an article on the Estonian newspaper industry, where he wrote about Johann Voldemar Jannsen: “The sole editor of the three magazines is Johann Jannsen, a former school teacher, whom his talented daughter Lydia, who is also known as a poet, brave the editorial team Provide assistance. ”Soon thereafter, a short review of Koidula's first volume of poetry followed, although Schott did not know who the author was. He then reviewed her debut and her play Der Vetter aus Saaremaa . He also discussed the drama Such a Mulk .

Later poems by Koidula appeared repeatedly in German, but never a separate collection of poems.

The following anthologies or magazines contain small (more) selections of Koidula's poetry:

- Magazine for Foreign Literature 1869, pp. 345–346.

- Songbook of a Baltic . Edited by Konrad Walther (d. I. Harry Jannsen). Part 1. Dorpat 1880, pp. 5–10, 50-51, 59-63.

- Estonian sounds . Selection of Estonian poems by Axel Kallas. Dorpat: Kommissions Verlag Carl Glück 1911, pp. 49–51.

- Estonian poems . Translated by W. Nerling. Dorpat: Laakmann 1925, pp. 25–31.

- We return home. Estonian poetry and prose. Adaptations by Martha v. Dehn-Grubbe. Karlsruhe: Der Karlsruher Bote 1962, pp. 44–45.

- Estonian poetry. Transferred by Tatjana Ellinor Heine. Brackenheim: Verlag Georg Kohl GmbH + Co 1981, pp. 18-23.

- Estonia 1/2000, pp. 29-39.

Works and editions of works

- Ojamölder yes temma minnia. ('The Grabenmüller and his daughter-in-law'). Tartu: H. Laakmann 1864 (but actually 1863). 68 pp.

- Waino-Lilled ('Field Trees'). Kuresaare: Ch. Assafrey 1866. 48 pp.

- Perùama wiimne Inka ('The last Inca of Peru'). H. Laakmann, Tartu 1866. 139 pp.

- Emmajöe Öpik . ('The Nightingale of Emajõgi'). H. Laakmann, Tartu 1866 (but actually 1867). 64 pp.

- Martiniiko yes Corsica. ('Martinique and Corsica'). H. Laakmann, Tartu 1869 (not published until 1874 due to censorship problems). 107 pp.

- Saaremaa Onupoeg. ('The cousin from Saaremaa.'). sn, Tartu 1870. 31 pp.

- Juudit ehk Jamaica saare viimsed Maroonlased. ('Judith or the last chestnuts of Jamaica'). H. Laakmann, Tartu 1871 (but actually 1870). 176 pp.

- Särane Mul'k, ehk Sada vakka tangusoola. ('Such a mulk or a hundred bushels of salt'). sn, Tartu 1872. 55 pp.

- Minu armsa taadile FJWiedemann 16-maks Septembriks 1880 ('My dear Papa FJ Wiedemann' ). H. Laakmann, Tartu 1880. 1 sheet.

- Teosed I (Luuletused) + II (Jutud ja Näidendid) ('Works I [poems] + II [stories and plays]'). Eesti Riiklik Kirjastus, Tallinn 1957. 433 + 448 pp.

- Luuletused. Tekstikriitiline väljaanne. ('Poems. Text Critical Edition'). Koostanud E. Aaver. Eesti Raamat, Tallinn 1969. 686 pp.

literature

Monographs

- Kreutzwaldi yes Koidula kirjawahetus I + II. Eesti Kirjanduse Seltsi Kirjastus, Tartu 1910/1911. 511 + 315 p. (Eesti Kirjanduse Seltsi Toimetused 5.1 + 5.2)

- Koidula ja Almbergi kirjavahetus. Trükki toimetanud Aug. Anni. Eesti Kirjanduse Seltsi väljanne, Tartu 1925. 120 pp.

- Aino Kallas : Tähdenlento. Virolaisen runoilijattaren Koidulan elämä. Toinen, laajennettu painos. Otava, Helsinki 1935. 296 pp.

- Lydia Koidula. Valimik L. Koidula 100. sünnipäeva ja 60. surmapäeva puhul avaldatud materjale. RK Poliitiline Kirjandus, Tallinn 1947. 156 pp.

- Karl Mihkla: Lydia Koidula elu ja looming. Eesti Raamat, Tallinn 1965. 358 pp.

- Herbert Laidvee: Lydia Koidula bibliograafia 1861 1966. Eesti Raamt, Tallinn 1971 (Personaalbibliograafiad II) 286 pp.

- Aino Undla-Põldmäe: Koidulauliku valgel. Uurimusi yes arti dress. Eesti Raamat, Tallinn 1981. 357 pp.

- Lydia Koidula 1843 1886. Koostanud Eva Aaver, Heli Laanekask, Sirje Olesk. Ilmamaa, Tartu 1994. 363 pp.

- Madli Puhvel: Symbol of Dawn. The life and times of the 19th century Estonian poet Lydia Koidula. Tartu University Press, Tartu 1995. 297 pp.

- Malle Salupere: Koidula. Ajastu taustal, kaasteeliste keskel. Tallinn: Tänapäev 2017. 568 pp.

items

- Gustav Suits: Koidula “Ojamöldri ja temma minnia” algupära . In: Eesti Kirjandus , 1932, pp. 97-107.

- Urmas Bereczki: Lydia Koidula's letters to Pál Hunfalvy . In: Estonia , 2/1985, pp. 6-15.

- Aino Undla-Põldmäe: Kirjanduslikke mõjustusi ja tõlkeid "Emajõe ööbikus" . In: Keel ja Kirjandus , 9/1986, pp. 528-538.

- Koidula . In: Harenberg's Lexicon of World Literature . Harenberg, Dortmund 1989. Volume 3, p. 1641.

- Malle Salupere: Uusi andmeid Koidula esivanemate kohta . In: Keel ja Kirjandus , 12/1993, pp. 708–716.

- Heli Laanekask: Koidula soome keel ehk hüva kui rent sisästa selkeäksi tulep . In: Lähivertailuja , 7. Suomalais-virolainen kontrastiivinen seminaari Tammivalkamassa 5. – 7. May 1993. Toim. Karl Pajusalu yes Valma Yli-Vakkuri. Turku 1994, 65-74 (Turun yliopiston suomalaisen ja yleisen kielitieteen laitoksen julkaisuja 44).

- Irja Dittmann-Grönholm : Koidula, Lydia (aka Lydia Emilie Florentine Jannsen) . In: Ute Hechtfischer, Renate Hof, Inge Stephan, Flora Veit-Wild (Hrsg.): Metzler Authors Lexicon . Stuttgart / Weimar 1998, pp. 259-260

- Cornelius Hasselblatt : Lydia Koidula in Baden . In: estonia , 1/2000, pp. 4-11.

- Gisbert Jänicke: About my dealings with Lydia Koidula . In: estonia , 1/2000, pp. 28-39.

- Heli Laanekask: Communicatioonistrateegiatest Lydia Koidula eesti-soome vahekeeles . In: Viro ja suomi: kohdekielet kontrastissa. Toimittaneet Pirkko Muikku-Werner, Hannu Remes . Lähivertailuja 13. Joensuu 2003, pp. 265-275.

- Epp Annus: Puhas vaim ning tema luud ja veri: Lydia Koidula ja Mati Unt . In: Looming , 5/2004, pp. 720-727.

- Piret Peiker: Postcolonial Change. Power, Peru and Estonian Literature . In: Kelertas, Violeta (ed.): Baltic postcolonialism . Rodopi, Amsterdam 2006, pp. 105-137.

- Cornelius Haasselblatt: Lydia Koidula: Emmajöe öpik + Särane mulk, ehk sada wakka tangusoola . In: Heinz Ludwig Arnold (Hrsg.): Kindlers Literatur Lexikon . 18 volumes. 3rd, completely revised edition. Verlag JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2009, Volume 9, pp. 232-233.

Web links

- Literature by and about Lydia Koidula in the catalog of the German National Library

- Lydia Koidulas biography and texts (Estonian)

- Article Lydia Koidula in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (BSE) , 3rd edition 1969–1978 (Russian)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Koidula yes Almbergi kirjavahetus. Trükki toimetanud Aug. Anni. Tartu: Eesti Kirjanduse Seltsi väljanne 1925.

- ↑ Ano Kallas. Tähdenlento. Virolaisen runoilijattaren Koidulan elämä. Tinen, laajennettu painos. Helsinki: Otava 1935, p. 176.

- ↑ Cornelius Hasselblatt: Lydia Koidula in Baden. In Estonia 1/2000, pp. 4-11 and 27.

- ^ Excerpt in German: Das Wienermädel. Translated by Irja Grönholm . In Estonia 1/2000, pp. 40-57.

- ↑ Madli Puhvel: Symbol of Dawn. Tartu: Tartu University Press 1995, p. 230.

- ↑ maaleht.delfi.ee

- ↑ a b Wilhelm Schott: Ein Ehstnischer Roman, in: Magazin für die Literatur des Auslands 1869, p. 471.

- ^ Gustav Suits: Koidula “Ojamöldri ja temma minnia” algupära, in: Eesti Kirjandus 1932, p. 103.

- ↑ See Piret Peiker: Postcolonial Change. Power, Peru and Estonian Literature, in: Kelertas, Violeta (ed.) 2006: Baltic postcolonialism. Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 105-137.

- ↑ dea.nlib.ee

- ↑ Estonian-German Calendar 1924, p. 161.

- ↑ Aino Undla-Põldmäe: L. Koidula “Vainulillede” algupärast, in: Keel ja Kirjandus 1968, p. 162; Friedrich Scholz: The literatures of the Baltic States. Their creation and development. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag 1990, pp. 201-202 (treatises of the Rhenish-Westphalian Academy of Sciences 80).

- ↑ a b Cornelius Hasselblatt: History of Estonian Literature. From the beginning to the present. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter 2006, p. 254.

- ↑ Cornelius Hasselblatt: Lydia Koidula: Emmajöe öpik + Särane mulk, ehk sada wakka tangusoola, in: Kindlers Literatur Lexikon . 3rd, completely revised edition. Edited by Heinz Ludwig Arnold . 18 volumes. Stuttgart, Weimar: Verlag JB Metzler 2009, Vol. 9, pp. 232-233.

- ↑ Cornelius Hasselblatt: History of Estonian Literature. From the beginning to the present. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter 2006, p. 261.

- ^ Wilhelm Schott: Magazines in Estonian Language, in: Magazine for the literature of foreign countries 1868, p. 223.

- ^ Wilhelm Schott: Die Nachtigall vom Embach, in: Magazine for the literature of foreign countries 1869, pp. 345–346.

- ↑ Wilhelm Schott: To Esthonian national literature, in: Magazine for literature of foreign countries in 1871, S. 442, respectively.

- ↑ Wilhelm Schott: An Estonian original drama, in: Magazine for the literature of foreign countries 1873, pp. 152-153.

- ↑ Cornelius Hasselblatt: Estonian Literature in German 1784-2003. Bibliography of primary and secondary literature. Bremen: Hempen Verlag 2004, pp. 60–62.

- ↑ Eestikeelne raamat 1851-1900. I: AQ. Toimetanud E. Annus. Eesti Teaduste Akadeemia Raamatukogu, Tallinn 1995, p. 318.

- ^ Jokingly pejorative term for a resident of Southwest Estonia.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Koidula, Lydia |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Jannsen, Lidia Emilie Florentine |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Estonian writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 24, 1843 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Vändra |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 11, 1886 |

| Place of death | Kronstadt |