Old Town (Stadtschwarzach)

The medieval old town of Lower Franconian Stadtschwarzach is a historical settlement core of the former city. However, the municipality of Stadtschwarzach gave up its town charter in 1819 and had most of the external signs of urban appearance such as town walls removed in the period that followed. The former old town is placed under protection as a ground monument .

Geographical location

Stadtschwarzach lies in the center of the Schwarzacher valley widening , which presents itself as a wide alluvial cone of three smaller brooks. The old town itself is east of the Main , the only elevation in the urban area is still occupied today by the parish church Heiligkreuz. Today the area is densely populated, especially the proximity to the Benedictine abbey Münsterschwarzach with its mighty monastery church is characteristic of the former city. The contrast between the extensive monastery complex and the small-scale town shaped this section of the Main for centuries. Today new development areas of the 20th century surround the old city.

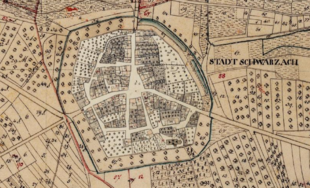

The old town of Stadtschwarzach was designed as a so-called " Rundling " with the market square in its geometric center, which suggests a planned construction. The town hall , built as an administrative center, can also be found on the market, along with the most important inns and stately buildings. The parish church moved to the southern edge of the city, where the cemetery was also to be found. The ground monument Altstadt Stadtschwarzach is now bordered by the abandoned trenches of the fortifications along the ring roads Wiesenleite, Am See, Am Stadtgraben and Kolpingstraße.

history

Establishment as a planned city

For a long time it was assumed that Stadtschwarzach was already the location of a women's monastery from the Carolingian era , which was later moved to the site of today's Münsterschwarzach. The more recent literature contradicts this assumption and describes Stadtschwarzach as a planned town of the Staufer period . The even, round floor plan of the settlement is just as indicative of this as the straight course of the street within the old town. The city was created "on the green field".

Other geographic features indicate the establishment of a planned city. The place was not named after the Castellbach or Silberbach, where Stadtschwarzach is located. Instead, the place was named after the Münsterschwarzach monastery built some distance away. Besides Stadtschwarzach had in the Middle Ages and early modern period with its district no access to economic important Main. Possibly the area of the young city was cut out of the existing districts. About 15 ha came from Hörblach , the majority, approx. 150 ha, was formerly part of Düllstadt .

The neighboring monastery, however, played a major role for the planned town of Stadtschwarzach. It is possible that the monk's settlement even initiated the foundation. The new town, which was first mentioned in 1228/1230, took in the monastery servants who originally settled in the settlement on Mannlehen west of the abbey, which is often threatened by floods . For a long time, the abbey determined social life through the right to appoint the most important offices.

The abbey 's support for the city of Schwarzach was also reflected in the granting of many rights. The young settlement was given market rights , the right to strike its own coins , and its own jurisdiction. The Zent Stadtschwarzach included many places on the northern Maindreieck. In addition, the citizens were allowed to surround their city with a wall. As in other cases, the abbey created its own economic and trading center in the immediate vicinity of the monastery. Stadtschwarzach soon became a pastoral center through its parish.

Destruction and reconstruction

At the transition to the late Middle Ages, the city got into conflicts between the Counts of Castell , the Münsterschwarzach monastery and its overlords, the Würzburg prince-bishops . After several armed conflicts, a compromise was finally reached: the three gentlemen shared control of the city. A parish church was mentioned for the first time in 1326 and rose in the middle of the 14th century to become an independent power factor up to the Steigerwald ( Großbirkach ), independent of the older monastery parish .

In the years 1401 and 1409 Stadtschwarzach was attacked and partly burned down by the troops of Heinrich Toppler von Rothenburg and the Lords von Aufseß. It is not known what effects these events had on the settlement in changing the cityscape. Despite these hostilities were able to build a new church, which by on January 3, 1424 the city of Black Achern, Auxiliary Bishop Eberhard benediziert was. However, construction on the choir of the Kreuzkirche had only begun in 1475. The church had meanwhile become a destination for pilgrims.

In 1525 the German Peasants' War broke out and the Stadtschwarzacher joined the peasant crowd. They set fire to the Münsterschwarzach monastery, burned down Stephansberg Castle and took part in the siege of Marienberg Fortress. After the uprising was put down, three ringleaders were executed on the market square of the city of Schwarzach . After these events, the monks wanted to get rid of the remaining rights to the settlement as quickly as possible and sold them to the Würzburg bishop in 1531.

In 1714 the town hall of the city was built in its current form, perhaps its predecessor was destroyed in the Thirty Years War . Stadtschwarzach also suffered from many wars in the 18th century. In 1758 you had to make contributions to a Prussian corps. In 1792 Austrian troops were in quarters. The Main crossing between Schwarzenau and Stadtschwarzach, which in the meantime was served by a ferry , made the Schwarzach Basin a center of the coalition wars in Franconia.

Loss of town charter

With the (second) transition to Bavaria in 1814, Stadtschwarzach finally became part of the kingdom. The Napoleonic Wars and secularization had already led to the abbey of Münsterschwarzach being dissolved at the beginning of the 19th century. This destroyed the centuries-old connections that had formed the economic basis for the city. In 1816, the town's farmers were also hit by a bad harvest. Those responsible, in particular the city's magistrate , finally decided in 1818 to forego the privileges of a city and henceforth to operate as a market town.

Above all, administrative costs were saved. The outward signs of a city, symbolized by the fortifications, had already disappeared around 1791 when most of the walls were torn down and the moat was leveled. In the 19th century the Würzburger / Kitzinger Tor disappeared in the direction of the Main. In the period that followed, the cityscape changed significantly without taking into account the historical structures that had evolved. Today, Stadtschwarzach has hardly any urban features, but has again become more central to the places in its surrounding area due to the municipal reform .

Streets and squares

The Stadtschwarzach old town was formed by the three main streets that come from the respective city gates to the market square in the center and each lead away from this square at an angle of 120 °. The side streets, on the other hand , are arranged concentrically around the market, forming a three-quarter ring (there is no ring road in the northeast). In addition, they are now supplemented by the streets running along the former moat, which also lead in a ring around the old town. Originally the city had 96 house numbers, street names did not exist. The current streets of the former old town have the following names:

|

|

In the 19th century, the city was still divided into four quarters , which differed just as much in their appearance as in their population composition. The northeast quarter was far less populated. The farms were located here, as there was more space available for house gardens and smaller fields within the city walls. Merchants and artisans spread over the other three quarters . The current names Schmiedsgasse and Häfnergasse still give evidence of this.

The center of the settlement was the elongated street market , today's marketplace. Among other things, the town hall was located here as the city's representative building. The so-called Engelwirtshaus was also an important social center. The connection to the long-term landlord, the neighboring monastery, was established through a stately tithe barn . The church, on the other hand, stood a little further south on the highest point of the settlement.

Historical appearance

In contrast to many other cities along the Main Triangle , the structures of the old town have not been preserved in Stadtschwarzach. That is why you have to rely on historical representations that convey a picture of the city. The drawings in the bishop's chronicle of Lorenz Fries , however, do not show Stadtschwarzach, but represent an idealized, late medieval city. In contrast, a rough hand drawing on a district map around 1667 gives a more realistic picture.

The city was surrounded by a stone wall, remains of which have been preserved along the outer ring roads. The last wall probably came from the 15th century and was constructed from rubble masonry . Small half towers were added to the wall in several places, and some real towers may also have been owned. Perhaps you can see the prison tower in the picture on the far right. The center of economic life were the three gatehouses , which were also the only entrances to the city. The Bamberg and the Würzburger / Kitzinger Tor were massive stone buildings, while the Schweinfurt Tor was partly made with half-timbering . It ended with a half-hip roof .

The current appearance of Stadtschwarzachs manages almost without urban buildings. After the Schweinfurt and Bamberger Tor had already disappeared in the last decades of the 18th century, before the city charter was lost, it took until the 1830s for the Kitzinger Tor to be demolished as well. Today two columns remind of the former location of this gate. Immediately south of the Schweinfurter Tor, the tithe barn of the Münsterschwarzach Abbey (Schmiedsgasse 2), which is another representative building in the city center, was located. It was built with a two-storey, pointed roof in 1516, but it was heavily redesigned in 1953.

However, two buildings still remind of the city's past. The town hall on today's market square dates from 1714. It presents itself as a two-storey, eaves-mounted hipped roof building. In the direction of the market square, a small roof turret was attached to the building. Several coats of arms of Würzburg prince-bishops refer to the historical links between the city and their domain. The remains of a are at the Marketplace side neck pillory in the building as spoils admitted. Maybe it was taken over from the previous building.

The Holy Cross Church in the very south of the old town was first mentioned in 1326 and was initially closely linked to the Münsterschwarzach Abbey, as the abbots also exercised the right of patronage . The current church was built in the 15th century, with the retracted choir being the last element to be completed in 1475. In 1866 the late medieval nave was torn down in order to have more space for the believers. The characteristic Echterturm with the pointed helmet disappeared after a lightning strike in 1940 and was replaced by today's pyramid helmet. → see also: Heiligkreuzkirche (Stadtschwarzach)

literature

- Franziskus Büll: The Monastery Suuarzaha. A contribution to the history of the Münsterschwarzach women's monastery from 788 (?) To 877 (?) . Münsterschwarzach 1992.

- Franziskus Büll, Josef Gerlach: Schwarzach am Main in old views . Zaltbommel NL 1991.

- Hans-Eckhard Lindemann: Historic town centers in Main Franconia. History - structure - development . Munich 1989.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Hans-Eckhard Lindemann: Historic town centers in Mainfranken. History - structure - development. Munich 1989. pp. 51-53.

- ^ Franziskus Büll, Josef Gerlach: Schwarzach am Main in old views . Zaltbommel NL 1991. Picture 28.

- ^ Franziskus Büll, Josef Gerlach: Schwarzach am Main in old views . Zaltbommel NL 1991. Picture 31.

- ↑ Franziskus Büll: The Monastery Suuarzaha. A contribution to the history of the Münsterschwarzach women's monastery from 788 (?) To 877 (?) . Münsterschwarzach 1992. S. 53 u. 58.

- ^ Franziskus Büll, Josef Gerlach: Schwarzach am Main in old views . Zaltbommel NL 1991. Photo 57.

- ^ Franziskus Büll, Josef Gerlach: Schwarzach am Main in old views . Zaltbommel NL 1991. Photo 35.

- ^ Franziskus Büll, Josef Gerlach: Schwarzach am Main in old views . Zaltbommel NL 1991. Picture 18.

- ^ Franziskus Büll, Josef Gerlach: Schwarzach am Main in old views . Zaltbommel NL 1991. Picture 33.

Coordinates: 49 ° 47 '58.8 " N , 10 ° 13' 49.6" E