Anatolia hypothesis

The Anatolia Hypothesis postulates the transfer of cultures , especially for languages , agriculture and livestock farming, to Europe through migration from Anatolia . In a narrower sense, it is seen as the spread of an Indo-European original language from Anatolia to Europe in connection with the Neolithic Revolution . It was formulated in the late 1980s by the British archaeologist Lord Colin Renfrew . The Anatolia Hypothesis locates the origins of the Indo-European languages in the Middle East.

In a broader sense, it postulates the spread of population groups to Central Europe, as a result of which agriculture and cattle breeding established themselves, although membership of a special language family remains open.

Archaeological background

→ Main articles Neolithic , Neolithic , Kurgan hypothesis

There are different hypotheses about the spread of the Indo-European languages . The Anatolia hypothesis was preceded in the 1950s by the Kurgan hypothesis by Marija Gimbutas , which Renfrew criticized.

In contrast to Gimbutas, Renfrew emphasizes that successful newcomers ( immigrants ) in the course of the colonization of Europe must have brought with them a technology that was superior to the previous one. There was only one event in prehistory and early history that brought about a radical improvement in living conditions: the development of agriculture, more precisely arable farming and cattle breeding in the course of the Neolithic era. Cultivation of einkorn , emmer and barley as well as the domestication of sheep and goats can be documented with the beginning of the pre-ceramic Neolithic first in the Middle East , especially in southeastern Anatolia and Upper Mesopotamia.

In his presentation from 2003, Renfrew assumes a gradual immigration of the Indo-European languages, also known as the “Indo- Hittite model” . The modified hypothesis primarily integrates the latest findings on the genetics of European populations (spread of haplogroups );

- since 6,500 BC The Neolithic expansion from Anatolia via the Balkan Peninsula ( Starčevo culture , Körös-Cris culture ) to the Central European ribbon ceramics took place;

- against 5,000 BC With the spread of the Copper Age cultures, the Indo-European languages were divided into three parts in the Balkans, split into a north-western European branch (Danube region), a Balkan branch and an eastern steppe branch (ancestors of the Tocharians ).

- only after 3000 BC The split of the language families from the Urindo-European ( Greek , Armenian , Albanian , Indo-Iranian , Baltic Slavic ) took place.

Arguments for the Anatolia Hypothesis

The following arguments support the Renfrew hypothesis:

- The bearers of the Neolithic Revolution who emigrated from Anatolia probably brought their own language with them. In the Anatolia Hypothesis, the Indo-European original language is taken into account.

- The genetic studies of Robert R. Sokal provide support for the hypothesis about the emigration of population groups from Anatolia to the western Mediterranean region . This has been repeatedly confirmed in the meantime, but has nothing to do with the hypothetical claim of the simultaneous spread of the developed Urindo-European. Genetic research in particular does not provide this, because the “Indo-Europeans” have not yet, and perhaps never, can be genetically determined.

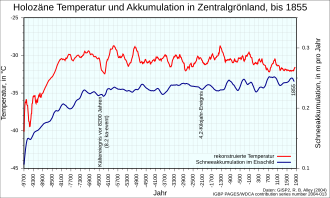

- During the Atlantic , which was blurred from approx. 8000 BC. Until approx. 4000 BC BC in Northern Europe and the Middle East showed, there was a heat optimum and the development of the warmest and wettest period of the Blytt-Sernander sequence , also known as the " Holocene Optimum". This temperature optimum was interrupted by the Misox fluctuation , a sharply delimited, relatively short-term climate change around 6200 years BC. About 100 years in duration. In Anatolia and the Middle East ( Mesopotamia ), the climate had cooled down during the Misox fluctuation with simultaneous aridification . This may have been the reason for climate-related emigration .

Arguments against the Anatolia Hypothesis

The following arguments oppose Renfrew's hypothesis:

- For early history, immigration to certain areas with an impact on the population composition could be shown, in which the language of the immigrants ( immigrants ) prevailed, but the culture of the autochthonous natives continued to dominate and at most was further developed. Examples are in particular the German-speaking area of the Roman Empire as well as in the area of today's Hungary and in North Africa (the Romans took over the Punic agriculture and the Arabs the Byzantine ). In contrast, large areas could also be conquered with relatively small armies, as the examples of the Visigoths in Spain, the Vandals in Africa or the Lombards in Italy show.

- According to archaeological findings, it was established in the Middle East from around 7000 BC. And delayed agriculture in Central Europe. In early Neolithic regions in Spain (see e.g. Los Millares and El-Argar cultures ), Italy and Greece (here before the immigration of Balkan Indo-Europeans in the early Helladic period), carriers of the Indo-European language encounter non-Indo-European peoples who have lived there for a long time and have developed agriculture. Renfrew's theory also provides no explanation for the non-Indo-European language islands, some of which were first settled in the Neolithic, such as on the Apennine peninsula, in the Aegean Sea , on the islands of Crete and Cyprus, and among the pre-Indo-European population in Greece, the ( Pelasgians in ancient sources).

- In Asia Minor, who were also in the center Hattians , in the east the Hurrians and to the south the Semites before spread of the Hittites established and operated agriculture. It was later taken over there by the Hittites . In India, the Indus culture of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, which preceded the Indo-European advance (earlier for Dravidian , now more Austro-Asian ), was already farming. In the southeast, the Sumerians and Elamites also spoke clearly non-Indo-European languages (apart from the Semites). If around 1500 to 2000 BC If at most small parts of Asia Minor were Indo-European, the agricultural cultural advantage and the advantage of the larger population of the Indo-Europeans cease to exist. Even in the Mitanni empire, the upper class was Indo-European (based on traditional names), but the broader population spoke Hurrian, as in Nuzi. The spread of the Indo-European original language to Persia , India and West Turkestan ( Tocharic ) from Anatolia due to a population explosion as a result of the existing agricultural techniques of the Indo-Europeans is therefore implausible, but not excluded, as religious or political circumstances could also have led to the spread of the language .

Synthesis - Genetic Research

The population geneticist Luigi Cavalli-Sforza published a synthesis of Renfrew's Anatolia hypothesis and Gimbutas' Kurgan hypothesis . In his opinion, farmers had brought an ancient Indo-European from Anatolia and spread it in Europe; in a second wave, the remaining Indo-European languages would have spread from the Kurgan area. Cavalli-Sforza presents three main archaeogenetic interpretations of investigated human genetic material, the "genetic tableau of Europe":

- a first, probably related to the spread of agriculture from the Middle East,

- a second, which shows a variation from north to south (i.e. allows a correlation to the climate) and is possibly connected to the spread of the Uralic language family,

- a third, which describes an expansion starting from the Kurgan region and connects it with the spread of the Indo-European languages, and the first relates to agriculture, see above.

As Luigi Cavalli-Sforza wants to show on the basis of a large number of human genetic studies, his hypothesis is not a singular one . The introduction of arable farming and animal husbandry is associated with significantly higher population densities (factor 10–50) and a temporary population explosion. This can be demonstrated in various places - for example in northern China as a result of millet cultivation and in southern China for rice - and correlates with the data from archaeogenetic studies of human genetic material . The connection of his first main interpretation with the spread of agricultural culture seems to be obvious. And the counter-thesis that arable farming was not necessarily also the carrier of a specific language family is seen by him as implausible. However, this language family does not have to be identified with Indo-European; it could just as well be any otherwise extinct linguistic substrate . In addition, the expansion of agriculture in South Asia could not be associated with the Indo-European language.

literature

- Colin Renfrew: The Indo-Europeans - from an archaeological point of view. In: Spectrum of Science. Dossier: The Evolution of Languages, 1/2000, ISSN 0947-7934 , pp. 40–48.

- Colin Renfrew: Archeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins. Cambridge 1990, ISBN 0-521-38675-6 .

- Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza: Genes, Peoples and Languages. The biological foundations of our civilization. WBG, Darmstadt 1999, DNB 957681542 .

- Jürgen E. Walkowitz: The language of the first European farmers and archeology In: Varia neolithica III, 2004, ISBN 3-937517-03-0

- Harald Wiese: A journey through time to the origins of our language. How Indo-European Studies explains our words. Logos Verlag Berlin, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8325-1601-7 .

- Remco Bouckaert, Philippe Lemey, Michael Dunn, Simon J. Greenhill, Alexander V. Alekseyenko, Alexei J. Drummond, Russell D. Gray, Marc A. Suchard, Quentin D. Atkinson: Mapping the Origins and Expansion of the Indo-European Language Family. Science Vol. 337 Aug 24, 2012, pp. 957-960

- Expansion of Indo-European languages. Map. from Remco Bouckaert, et al .: Mapping the Origins and Expansion of the Indo-European Language Family. Science Vol. 337 Aug 24, 2012, pp. 957-960

Web links

- http://www.geocurrents.info/ ; an excellent and thorough analysis despite small errors.

- Europe's “original language” originated in Anatolia. Science news

- Cult & History. Old Europe I - "Neolithic Revolution"

- When and where was proto-Indo-European?

Individual evidence

- ^ Colin Renfrew: Archeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins. Cambridge 1990, ISBN 0-521-38675-6 .

- ↑ R. Bouckaert, P. Lemey et al. a .: Mapping the Origins and Expansion of the Indo-European Language Family. In: Science 337, 2012, pp. 957-960, doi: 10.1126 / science.1219669 . PMC 4112997 (free full text).

- ^ Marija Gimbutas: The Kurgan Culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe. Selected Articles from 1952 to 1993. Institute for the Study of Man, Washington 1997, ISBN 0-941694-56-9 .

- ^ Colin Renfrew: Time Depth, Convergence Theory, and Innovation in Proto-Indo-European. In: Alfred Bammesberger, Theo Vennemann (Ed.): Languages in Prehistoric Europe. 2003, ISBN 3-8253-1449-9 .

- ↑ Harald Haarmann: The riddle of the Danube civilization. The discovery of the oldest high culture in Europe. CH Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-62210-6 , p. 31 f.

- ^ Russell D. Gray, Quentin D. Atkinson, Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin . In: Nature . tape 426 , no. 6965 , 2003, p. 435-439 , doi : 10.1038 / nature02029 ( PDF ).

- ^ Robert R. Sokal, Neal L. Oden, Chester Wilson: Genetic evidence for the spread of agriculture in Europe by demic diffusion . In: Nature . tape 351 , no. 6322 , May 9, 1991, pp. 143-145 , doi : 10.1038 / 351143a0 .

- ↑ cf. RB Alley: The Younger Dryas cold interval as viewed from central Greenland . In: Quaternary Science Reviews . January 2000, doi : 10.1016 / S0277-3791 (99) 00062-1 .

- ↑ Dieter Anhuf, Achim Bräuning, Burkhard Frenzel, Max Stumböck: The development of vegetation since the height of the last ice age. National Atlas of the Federal Republic of Germany - Climate, Flora and Fauna, pp. 88–91.

- ↑ The climate level corresponds to pollen zones VI and VII.

- ↑ Peter Rasmussen, Mikkel Ulfeldt Hede, Nanna Noe-Nygaard, Annemarie L. Clarke, Rolf D. Vinebrooke: Environmental response to the cold climate event 8200 years ago as recorded at Højby Sø, Denmark. In: Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland Bulletin 15, 2008, pp. 57-60.

- ^ Bernhard Weninger, Eva Alram-Stern, Eva Bauer, Lee Clare, Uwe Danzeglocke, Olaf Jöris, Claudia Kubatzki, Gary Rollefson, Henrieta Todorova: The Neolithization of Southeast Europe as a Result of the Abrupt Climate Change around 8200 cal BP . In: Detlef Gronenborn (ed.): Climate change and cultural change in Neolithic societies in Central Europe, 6700–2200 BC. Chr. Verlag des Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseums, Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-88467-096-4 , p. 75–117 ( online [PDF; 2.2 MB ]).

- ^ Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza: Genes, Peoples and Languages. The biological foundations of our civilization. 1999.