Borobudur

| Borobudur | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

|

|

| General view of the temple complex |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | Culture |

| Criteria : | i, ii, vi |

| Reference No .: | 592 |

| UNESCO region : | Asia and Pacific |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1991 (session 15) |

Borobudur (also Borobodur ) is the largest Buddhist temple complex in the world.

The colossal pyramid is located around 25 kilometers northwest of Yogyakarta on the island of Java in Indonesia . Borobudur was recognized as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1991 . It is considered the most important building of Mahayana Buddhism on Java.

The stupa was probably built between 750 and 850 during the rule of the Sailendra dynasty. When the center of power in Java shifted to the east in the 10th and 11th centuries (perhaps also in connection with the eruption of the Merapi 1006), the complex fell into oblivion and was buried by volcanic ash and overgrown vegetation. In 1814 it was rediscovered; Europeans brought them back to light in 1835. A restoration program from 1973 to 1983 brought large parts of the complex back to its former glory.

A total of nine floors tower on the square base of 123 m length. On the walls of the four stepped tapered galleries there are bas-reliefs with a total length of over five kilometers, which describe the life and work of Buddha . Above are three concentrically tapering terraces with a total of 76 stupas, which frame the main stupa of almost 11 m in diameter.

The building was restored from 2011 to 2017 with financial and material aid from the Federal Republic of Germany .

Location and surroundings

The Borobudur was built on a small hill in the Kedu Basin, a fertile valley surrounded by mountains. To the south and southwest by the Menoreh Mountains, to the north and northeast by the Merapi and Merbabu volcanoes, and to the northwest by the Sumbing and Sindoro volcanoes. The temple is near the point where the Elo joins the Progo .

About the name Borobudur

The name is a combination of the words Bara and Budur; its meaning is unclear. Bara comes from the word Vihara , which denotes a complex of temples, monasteries or dormitories. Budur comes from the Balinese Beduhur , which means something like "above". Consequently, Borobudur means a complex of temples, monasteries or dormitories that are located on a hill.

In fact, remains of buildings that may have been a monastery have been found in the northwest part of the courtyard.

JG De Casparis made a discovery based on the inscriptions of Cri Kahuluan (842 AD). The name Borobudur is apparently derived from the name mentioned in the inscription . Unfortunately, the name mentioned there is not completely preserved. The full name must have been Bhumisambharabudhara , which means something like "the monks of the accumulation of virtues on the ten degrees of the Bodhisattva ". There is also a village near Borobudur called Bumisegara , which supports this thesis.

The date of construction

The exact time of the construction of the Borobudur is still unknown; there are no documents or certificates. Experts estimate the completion date from an inscription on the covered base of the Borobudur temple. These Sanskrit inscriptions are written in the Kawi spelling . After these characters were compared with other inscriptions from Indonesia, experts estimate the creation date to be around the year 800.

Central Java was ruled by kings of the Sailendra dynasty who were followers of Mahayana Buddhism . Since the Borobudur is a monument of Mahayana Buddhism , it is believed that it was built during the reign of these kings.

The Borobudur in oblivion

For a century and a half, Borobudur was the spiritual center of Buddhism in Java. With the fall of the Hindu Kingdom of Mataram in 919 and the relocation of political and cultural activities from Central Java to East Java, religious buildings in Central Java such as Borobudur were neglected and gradually fell into disrepair. There may have been a volcanic eruption around 930 that drove the region's population away. Tropical vegetation overgrown the stones. In particular, the higher parts collapsed while other parts were damaged. The Borobudur was forgotten for almost 1000 years.

Rediscovery and restoration

When it was first mentioned in modern times, in 1709, it was just referred to as Borobudur Hill. The entire monument was covered with earth and vegetation and appeared to be just a hill.

The actual rediscovery took place in 1814 by Thomas Stamford Raffles , the then English governor of Java, who had received a report on his trip to Semarang that there was a large monument in the area of Bumisegoro, which was called Borobudur. Raffles instructed the Dutch engineer HC Cornellius to make a study of the situation. The report is the first detailed record of the existence and condition of Borobudur. Cornellius' drawing is an important document about the state before the excavation and restoration work began. Otherwise nothing else apparently happened at that time. In 1835 a citizen of Kedu named Hortman took the initiative and cleaned up the temple area so that part of the shrine was finally visible.

Since its discovery by Raffles, the Borobudur has been restored several times due to damage. For example, a major earthquake struck the island of Java in 1548 , possibly causing severe damage to the monument, possibly including the ultimate collapse of the upper stupas.

In 1885, public interest was revived when JW Ijzerman, a Dutch army engineer, found the hidden reliefs of Mahakarmawibangga at the base of the temple. Some of them were only preserved in outline - in other opinion they were never completed because the construction plan was changed and the foot was closed with another retaining wall. Experts made initial suggestions to restore the shrine. One of the suggestions was to secure the reliefs in a special museum. Interest waned and the borobudur was in danger of being forgotten.

In 1896 the Dutch colonial authorities presented the monument to King Chulalongkorn of Thailand . As was quite common at the time, he received five Buddha statues, two lions, a Makara (gargoyle), some ornaments of the entrance, parts of the staircases and an unusual, large Gopala statue from Dagi Hill in the Near the Borobudur originated.

In 1900 Dutch authorities set up a committee to restore Borobudur. A member of the committee suggested that a large zinc roof be built on 400 iron pillars over the temple to protect it from the weather. This proposal was rejected.

In 1905 a plan for the most important measurements to restore and protect Borobudur was adopted. Under the direction of the archaeologist Dr. Theodor van Erp began the restoration work. In 1911 the Borobudur was in better condition, numerous stupas had been restored, the walls and floor slabs straightened. It cannot be ruled out that the large-scale uncovering of the monument without simultaneous security measures did more harm than good in the long term.

In 1955, the Indonesian government presented a new plan to UNESCO to save Borobudur and other temple sites. The government of Indonesia raised part of the money it needed. In 1971 UNESCO held its first meeting in Yogyakarta to discuss the plans. In 1973 the Indonesian President officially started the restoration work. Finally, in 1983, exactly ten years later, the work was finished and Borobudur was open to the public again.

In November 2010, a major campaign was launched to clean the temple complexes from acid ashes after an eruption of the Merapi volcano .

The structure of the Borobudur

Form

The Borobudur was built as a hill with an inner stone filling and has the shape of a step pyramid. If people wanted to carry out their religious tasks, they did so in the open air on the foot of the monument. Alignments of steps and stairways lead to the top of the step pyramid on four sides.

Seen from the outside, the Borobudur is reminiscent of a walled hill. Its structure consists of six square levels, three circular terraces and a central stupa forming the apex . The Borobudur is full of Buddhist symbols and represents the replica of the universe.

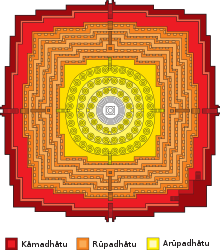

According to Buddhist cosmogony , the universe is divided into three worlds: Ārūpyadhātu ( Sanskrit ; Pāli : Arūpaloka; Tib . : gzugs.med.pa'i khams), Rūpadhātu (Pāli: Rūpaloka; Tib: gzugs.kyi khams) and Kāmadhātu (Pāmadhātu (Pāmadhātu) : Kāmaloka; Tib: 'dod.pa'i khams). Kamadhatu, the "lowest" world, is the human world, the "world of the senses". Rupadhatu is the transitional world in which people are released from their physical form and worldly affairs, the "Fine Body World". Finally, Arupadhatu, the world of the gods, is the world of perfection and enlightenment , the "incorporeal world".

The architecture of Borobudur was designed in accordance with this cosmology. Each part of the monument is dedicated to a different world. The Kamadhatu is a large rectangular wall on the outside of the foot of the monument. The rupadhatu rises above this base and consists of four rectangular terraces with processional paths decorated with numerous statues and 1,300 scenic and 1,200 figurative reliefs . Above it rises the Arupadhatu, consisting of three circular terraces with a large bell-shaped dome in the center. No matter from which perspective one looks at the building - it is always difficult to recognize this three-part basic structure.

The rectangular foundation is hidden, on which the step pyramid appears with an edge length of about 110 meters. The temple is reminiscent of a massive, round dome (hall?) With the rising stupa on top. The monument appears like a disordered collection of endless terraces, statues and niches. The architecture of the temple still impresses with its incredible precision and testifies to immense human work. 55,000 cubic meters of andesite stones or more than two million stone blocks were moved from the Progo River to the construction site. The rocks were first roughly hewn by the river before being pulled to the monument by elephants and horses.

Kamadhatu

The reliefs on the base level, the Kamadhatu, were covered with an extra wall before they were completely finished. There are two theories for this additional wall:

1. The whole structure started to slide and needed support.

2. It is possible that the scenes depicted were later perceived as too revealing.

There are two arguments in favor of theory 1: the impressive thickness of the widened base (a five meter thick layer of stones would not have been necessary to merely cover the reliefs) and the fact that the stability of the entire complex was also endangered as a late consequence of the 1911 restoration.

During the Japanese occupation, parts of the wall that contained reliefs from the Karmavibhanga , an ancient Sanskrit treatise on good and bad deeds and their consequences, were removed. These parts of the relief are on the southeast side. During the major restoration of 1973–1983, all reliefs were temporarily exposed and documented. Photos of the reliefs are exhibited in the complex's Archaeological Museum.

Rupadhatu

The rupadhatu begins with the first terrace. If we turn down the corridor to the left, we see the life of the Buddha depicted on the 120 main reliefs , as it is passed down in the Lalitavistara , a Sanskrit script . Another cycle begins on the same gallery, which is continued in the second and third gallery and illustrates the stories of the 500 earlier existences of the Buddha in 720 reliefs. The reliefs in the second to fourth galleries show Sudhana's search for wisdom and enlightenment ( Gandhavyuha ).

Arupadhatu

If we go up the monument, read the stories and climb the terraces, we will pass six gates. Before the final, top level, the arupadhatu, we have to go through double gates between the third and fourth terrace levels. These are called the double gates of Nirwikala. After we have passed these gates, our body leaves the material form, that of the rupadhatu, and goes into the disembodied mind, the arupadhatu. The Nirwikala is the final gateway that leads to the ultimate ultimate level of Buddhism. The best preserved gate was found on the side of the structure. As soon as we enter the Arupadhatu, we have a liberated and open feeling, unlike in the delimited, rectangular corridors of the terraces below. There are now three circular terraces in front of us.

On the terraces, 72 stupas built with lattice stones are geometrically arranged (small stupa-shaped structures), each of which contains statues of Buddha Vajrasatwa. The philosophy behind these imprisoned Buddhas is complex and not fully explored. Perhaps the grid-like structures represent a sieve-like border that separates the world of objectivity from the world of non-objectivity. It should be noted that the holes on the first two terraces are diamond-shaped, while those on the top terrace are square.

Buddha statues

In the Rupadhatu the Buddha statues are in the niches of the balustrades on the four terraces. On the first terrace there are 104 niches, on the second also 104, on the third terrace 88, on the fourth 72 and on the fifth 64, so that originally there were a total of 432 statues.

On the three upper, circular terraces, the arupadhatu, there are Dhyani -Buddhas or meditating Buddhas in a total of 72 seemingly perforated stupas built with lattice stones, which are arranged in three concentric circles on a round terrace each. On the first circular terrace there are 32 stupas, on the second 24 and on the third 16 statues.

So originally there were a total of 504 Buddha statues on the entire complex, of which around 300 are now mutilated - mostly their heads are missing - and 43 are completely missing.

At first glance, all Buddha statues seem to look the same, but on closer inspection, the statues differ from each other mainly in the position of their hands ( mudra ) . The statues in the niches on the first four balustrades show different mudras, on each side of the monument there are statues with the same hand position. However, all the statues on the fifth balustrade all have the same hand position, as do the 72 statues on the circular terraces.

So there are Buddha statues at Borobudur with a total of five different mudras, corresponding to the Mahayana concept of the five Dhyani Buddhas. The five cardinal points of the compass (east, north, west, south and zenith ) also find their correspondence here, with each cardinal direction being protected by a Buddha: Vairocana in the zenith, Akshobhya in the east, Amoghasiddhi in the north, Amitabha in the west and Ratnasambhava in the south . A mudra is assigned to each Buddha:

- "Bhūmisparśa Mudrā" of the Buddha Akshobhya (Aksobhya) in the eastern quadrant: his left hand lies with the palm facing up in his lap, with his right palm facing down he invokes the spirit of the earth to win his victory over evil spirits as well as his to witness inner strength.

- "Abhaya Mudrā" of the Buddha Amoghasiddhi in the northern quadrant: his right raised hand shows with the palm outward the gesture of fearlessness.

- "Dhyāna Mudrā" of the Buddha Amitabha in the western quadrant: both hands lie on top of one another, palms up in the lap, thus showing the gesture of meditation.

- “Varada Mudrā” of the Buddha Ratnasambhava in the southern quadrant: his right hand rests on his right knee, the open palm upwards, and thus shows the gesture of granting a wish.

- "Vitarka Mudrā" of the Buddha Vairocana on the fifth terrace: the gesture of the circularly curved fingers of the right hand shows that he gives teachings with an honest and pure heart (gesture of instruction).

Pilgrimage

On the former pilgrimage route to Borobudur there are two other small Buddhist temples: The temple of Mendut (approx. 4 km before Borobudur) and the temple of Pawon (approx. 2 km before Borobudur).

- Candi Mendut , about four kilometers east of Borobodur, has a square floor plan and a high base. To the northwest, the entrance side, the square is extended by a porch. Here a fourteen-step staircase leads to a wide path of transformation ( Pradakshinapatha ), which the pilgrim walks around in a clockwise direction . In this way, the Buddha pays homage to the Buddha before he enters the interior, where he finds three large trachyte statues in the main room : In the middle, Buddha Vairocana sits as the teacher of humanity, but not in the lotus position , but in the European way with feet standing side by side. It is the most important Buddha figure in Java in terms of art history. He is surrounded by two bodhisattvas, Avalokiteshvara on his left and Manjushri on his right . The outside of the staircase is richly decorated with relief jatakas , as well as a band around the entire base with 31 fields. As is so often the case in Southeast Asia, the banister is depicted in the Kala Makara motif. The pyramid- shaped roof of the temple rises in three steps, but the crown (probably a stupa) is missing. Candi Mendut has been changed several times and it is no longer possible to restore it to its original state.

- Also Candi Pawon , between Borobudur and Candi Mendut, located on the east-west line of the pilgrimage and was this in the time of the Sailendra dynasty (8-9. Century) built as. In the architectural structure and in the decorations it is similar to the Mendut, but is smaller and more complete, that is, its roof is crowned by four small and one larger stupa. The reliefs on the outer wall show a tree of life (Kalpavriksha) on each side , flanked by Kinnara-Kinnaris , above Apsaras "in the clouds" . As with Mendut, the interior has a cantilever vault ; the cult images have disappeared.

Hariti relief on the north wall of the temple

meaning

Borobudur is not only a unique religious monument, but also an important source of information on Javanese history. The depicted people, their clothes, houses, wagons, ships, equipment, instruments, dances etc. show courtly and rural life in Java in the 9th century in a way that is nowhere else to be documented.

The Archaeological Museum located on the site of the complex preserves numerous original stones and Buddhas that were replaced during the restoration 1973–1983. There is also a detailed report on the restoration work.

literature

- Peter Cirtek: Borobudur. Creation of a universe . 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Monsun, Hamburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-940429-08-7 .

- Jacques Dumarçay: The Temples of Java . Oxford University Press, Singapore 1989, pp. 27-29, ISBN 0-19-582595-0 .

- Jan Fontein: Entering the Dharmadhātu: a study of the Gandavyūha reliefs of Borobudur . Brill, Leiden 2012, ISBN 978-90-04-21122-3 .

- Jean-Louis Nou: Borobodur . Munich, Hirmer 1995. ISBN 3-7774-6460-0 .

- Heimo Rau: Indonesia . Kohlhammer Verlag , Stuttgart 1982, pp. 140-145, ISBN 3-17-007088-6 .

Web links

- Official website of Borobudur Park (English and Indonesian)

- Soekmono: Chandi Borobudur - A Monument of Mankind . The Unesco Press, Paris 1976. (Link checked on July 19, 2007)

- Pictures and film

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

Footnotes

- ↑ auswaertiges-amt.de: page no longer available , searching web archives: Restored with help from Germany: The Borobudur temple in Indonesia

- ↑ For details, see Fontein, Jan.

Coordinates: 7 ° 36 ′ 27 ″ S , 110 ° 12 ′ 15 ″ E