Boutilimit

| Boutilimit بوتلميت |

||

|---|---|---|

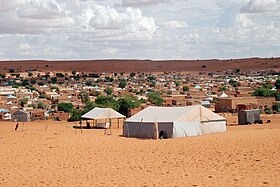

From the sand hill in the west across the city. The blue pavilion roofs made of corrugated iron are the climatically most favorable places to stay |

||

| State : |

|

|

| Region : | Trarza | |

| Department: | Boutilimit | |

| Coordinates : | 17 ° 31 ′ N , 14 ° 46 ′ W | |

| Residents : | 39,052 | |

| Time zone : | GMT ( UTC ± 0 ) | |

|

|

||

Boutilimit ( Arabic بوتلميت, DMG Būtilimīt ) is the capital of one of the six districts in the administrative region of Trarza in southwest Mauritania . The small town is an old handicraft center and famous for one of the largest collections of medieval Arabic manuscripts in West Africa. Founded by an Islamic saint in the 19th century, Boutilimit became a center of religious education.

location

Boutilimit is located 154 kilometers southeast of the state capital Nouakchott before the transition from the Mauritanian Sahara to the southern Sudan zone . Within a few kilometers, around the 17th parallel, desert areas with little vegetation change to grassy plains of dry savannah . The sand dunes ( Erg ) in the vicinity do not allow any arable farming and make it difficult to expand housing. In addition to goats, some cattle are kept around Boutilimit, which otherwise can only be found further south in larger herds. Rain falls in the summer months to September / October mostly in the form of short, violent thunderstorms.

Today's arid environment was created by several periods of drought over the past centuries. The pre-colonial emirate of Trarza, the size of which corresponds roughly to today's administrative region, was involved in the gum arabic trade with the Europeans. Until the beginning of the 20th century, Boutilimit was known for its location in the middle of the Verek acacias , from which this tree sap is extracted. The disappearance of the forests led to a deterioration in soil quality.

Coming from Nouakchott, through traffic reaches the next town of Aleg on the only paved main road from west to east towards Mali, 108 kilometers southeast . In other directions there are only bad slopes.

history

A settlement was founded in the 19th century on the site of an old nomadic camp. This is where the name Boutilimit goes back, which translates as “place where a lot of millet grows”. The religious importance of the place is due to the holy Sheikh Sidiyya (1774-1868), called al-Kabir ("the great"). The marabout founded a religious center ( Zawiya ) here .

In his time, from around 1810, a collection of Islamic manuscripts began to be compiled, which has grown to over 2000 books, letters and contracts. The Koran school founded by Sidiyya and continued by his son Sidi Muhammad (1827–1869) and other family members made Boutilimit a center of Islamic learning. The founder's great-grandson, Ismaʿil Ould Sidi Baba (1900–1988) added other writings to the family library. There are similarly extensive manuscript collections in Mauritania in Chinguetti and Tichit , and smaller ones in Tidjikja and Kaédi .

The orientalist Louis Massignon was the first to publish a description of Sheikh Sidiyya's library in 1909. He divided the then 1195 writings into theological, legal and basic texts, of which he counted 683 printed versus 512 handwritten works. Published in the Parisian magazine Revue du Monde Musulman , this was the first description of an Islamic library in the Sahara.

French military leader Xavier Coppolani came up with a plan for a peaceful penetration of Mauritania. The French colonial territory filed in 1900 by the Senegal River as the northern border. In 1902, Sheikh Sidiyya Baba signed a peace treaty with Coppolani, which awarded the Trarza province and the province of Tagant to the east to the French. The sheikh from the Sidiyya family was probably the most influential marabout in southern Mauritania and a friend of the French at the time. French troops were present in the south of Mauritania until 1904, and the subsequent “pacification” lasted considerably longer. By 1934, traveling in the region had become safe for western foreigners. That year the French travel writer Odette du Puigaudeau got to see the library. In her experience report, she mentions editions of the Koran from various countries in North Africa, including one from the 13th century, as well as other valuable writings, the quality of which she found to be blatantly disproportionate to the inadequate situation in which they were kept. In collaboration between the Nouakchott-based Institut Mauritanienne de Recherche Scientifique (IMRS) under the direction of Ahmadu Ould 'Abd al-Qadir and the University of Tübingen , Rainer Oßwald and Ulrich Rebstock produced microfilms and catalogs of ancient writings across the country between 1980 and 1985 .

The French colonial rulers built schools based on the Western model in the larger settlements, the main aim of which was to train local staff for administrative tasks. The traditional Islamic educational institutions of the Berber-Arab Bidhans , the mahadras , were oppressed. Resistance to this school policy came particularly from the local Bidhan elite, who preferred to send the children of their workers and slaves to French schools rather than their own. The women in particular resisted being forced to attend by French school inspectors. Nowhere in the French colonial areas of Africa was the French school model as unpopular as in the Arab part of Mauritania.

To compensate for this, the French designed a project of partially Arabic lessons by setting up four madrasas , the subjects of which were predominantly geared towards traditional Islamic education. The first of these Islamic Arab universities was founded in Boutilimit in 1914. Their curriculum was based on that of the Mahadras, the core of which consists of Koran studies, Islamic law ( šarīʿa ), Islamic traditions ( hadīth ), grammar and Arabic literature . The additional subjects introduced were French, arithmetic, geography and history. Schoolchildren also traveled from distant parts of the country and were housed in tents in the traditional way. 20 years after it was founded, the madrasa was rated as an exemplary and flourishing institution. The three other madrasas based on this model - founded in 1933 in Timbédra , 1936 in Atar and 1939 in Kiffa - were not successful because their focus was too much on French education.

In 1953 the madrasah was renamed from Boutilimit to Institut Musulman . In 1961, a year after independence, it became the Institut National des Hautes Etudes Islamiques, but it did not start operating until 1968. When it was relocated to Nouakchott in 1979, the Islamic educational institution, now financed by Saudi Arabia, was renamed Institut Supérieur d'Etudes et de Recherches Islamiques (ISERI).

When Mauritania gained independence, the few inhabitants of the place lived mostly in tents. In 2000 the census showed 22,257 inhabitants. For 2005, 27,170 inhabitants were calculated. According to another calculation, the number should have grown to 38,952 inhabitants in 2010. The importance of the place before and after independence was much greater than the population figures suggest.

Cityscape

The city has developed from a street village about two kilometers along the thoroughfare in a broad valley between sand hills. At the southwest end, the road leaves the valley and turns east towards Aleg. Straight ahead, the plain continues as Oued , in which only Calotropis procera thrives. The remains of former French buildings are preserved at the highest point of the hill in the northwest. The road to Nouakchott goes far around the hill before turning west. Acacia trees , from which gum arabic can be extracted, stand on the sand dunes . Agricultural cultivation is limited to tiny experimental gardens in which millet and melons are planted with well irrigation.

Boutilimit's past as a nomadic settlement can be seen more than other cities. The transition from living in a nomad tent (Khaima) to settling in a brick building takes place in stages. Outside the city, former nomads who fled to the city due to drought or other economic difficulties set up their tents further apart. The next step towards sedentariness is a metal frame that is covered with fabric or corrugated iron to create an open pavilion. These mostly blue gable roofs stand out as patches of color between the one-story brown flat roof houses. The thin-walled houses made of hollow cement blocks are climatically unfavorable. They heat up in the sun and hardly let in any cooling wind. Often the tent roofs or pavilions erected next to the houses therefore remain the actual residence of the family. Woven straw huts ( tikkits ) are a rare semi-nomadic design in the south .

A study started in 2008 and financed by the Emirate of Qatar is intended to show the deficits of the infrastructure. In the city, which has grown unplanned, there is a lack of water supply for most of the houses, schools and educational institutions and an adequate health service. A college completed by the Department of Education in 2004 stands empty.

The bustling market in the center of town has the usual assortment of plastic goods and imported fabrics. A number of cookshops provide travelers with grilled meat. Boutilimit also has a long tradition in the manufacture of ironwork and leather housewares, which are available in some small shops. These are made by the caste of blacksmiths (Maʿllemīn) , whose field of activity includes not only iron but also wood processing. In the past, especially wooden and horn bracelets were decorated with encrusted (hammered in while hot) silver threads. The leather goods made by women include the now rare camel saddles ( Rahla ) and the ubiquitous armrest cushions ( Surmije ) . There are also carpets made from camel and goat hair. Most of the diverse housewares of the nomadic culture, which used to be elaborately made of wood and leather, are hardly in demand.

sons and daughters of the town

- Moktar Ould Daddah (1924-2003), first president of Mauritania, belonged to the local marabout tribe Oulad Berri.

- Ahmed Ould Daddah (born 1942), economist, civil servant and politician (RFD)

- Ismail Ould Bedde Ould Cheikh Sidiya (born 1961), engineer and politician

Web links

- Louis Werner: Mauritania's Manuscripts. Saudi Aramco World, November / December 2003, pp. 2–16 (Contains the assumption that a previously unknown grammar of Averroes was found in Boutilimit )

- The “Boutilimit” records. West African Arabic Manuscript Database

Individual evidence

- ^ Advisory Committee on the Sahel: Environmental Change in the West African Sahel. (PDF; 4.98 MB) National Academy Press, Washington 1983, p. 29

- ↑ Thomas Krings : Sahel. Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Niger. Islamic and traditional black African culture between the Atlantic and Lake Chad. duMont, Cologne 1982, p. 226

- ↑ Charles T. Stewart: Colonial Justice and the Spread of Islam in the early Twentieth Century. In: David Robinson, Jean-Louis Triaud (eds.): Le temps des marabouts. Itinéraires et strategies islamiques en afrique occidentale française v. 1880-1960. Karthala, Paris 1997, p. 63

- ↑ Graciano Krätli: The Book and the Sand: Restoring and Preserving the Ancient Desert Libraries of Mauritania - Part 1 (PDF, 275 kB) World Libraries, Vol 14, No. 1, Spring 2004, p. 9.

- ↑ Odette du Puigaudeau : Barefoot through Mauritania. Two daring female adventurers cross the desert. Piper, Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-89405-279-9 (French first edition 1936)

- ↑ Michael Hirth: Traditional education and upbringing in Mauritania. On the development potential of the Moorish mahadra. (Europäische Hochschulschriften, Vol. 175, Series XXXI Political Science) Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. a. 1991, pp. 135f

- ↑ Ursel Clausen: Islam and national religious policy: The case study of Mauritania. (PDF; 148 kB) German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg, January 2005, p. 12

- ↑ Anthony G. Pazzanita: Historical Dictionary of Mauritania. The Scarecrow Press, Lanham (Maryland), Toronto, Plymouth, 3rd ed. 2008, p. 102

- ↑ 2005 population estimates for cities in Mauritania. Mongabay.com

- ^ Mauritania: Les villes les plus grandes avec des statistics de la population. World Gazetteer

- ^ Boutilimit, Mauritania Regeneration and modernization of the city. ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Keios Consulting Company