Bressehaus

When Bresse house is a timber-framed building in post and beam construction , which with mud bricks made of plied is. A large hipped roof protects the sensitive walls from rain and snow. Almost all of the house faces north-south, with the roof often lowering on the north side. This orientation offers optimal protection from the cold breeze , which is also guided over the house through the lower roof on the north gable side. The living rooms are on the south side, with the main facade facing the morning sun. Usually every room has one or two doors to the outside so that no space is lost for corridors.

The cantilevered roof is supported by brackets or pillars, with the lower part of the roof being attached to a second, shortened rafter , creating a pitched roof. The canopy allows items to be stored dry around the house and, in particular, to hang up corn on the cob on the rafters for drying.

The landscape of the Bresse is characterized by its agricultural buildings, the villages are often highly sprawled, the farms are often far from the village, close to water, forests, preferably on slight elevations.

features

Truss

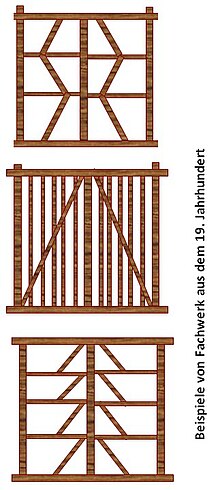

While the half-timbered structure was still large and simple in the 14th and 15th centuries, more and more complicated shapes developed in the 16th to 18th centuries, on the one hand to give the building more stability, but on the other hand also as a visual design. Crossed swords that formed a St. Andrew's cross enjoyed particular popularity . The half-timbered building was preserved until around the middle of the 19th century. Then began a change by increasing in the southern Bresse rammed earth was used frequently with reinforced corners by these were built with bricks or stones and creates the facade surfaces with rammed earth. In northern Bresse, brick has been used in general since the 19th century, at best bricks of poor quality. At the same time, the hip on the gable side was shortened to a crippled hip or even to a simple gable , with the gable-side canopy being almost completely dispensed with.

Courtyard shapes

Two courtyard forms in particular have developed. On the one hand there is the one- roof courtyard , which is divided across and where the threshing floor is usually in the middle (Mittertennhaus), on the other hand the two-sided courtyard , which is possibly supplemented with additional outbuildings. The main buildings usually face north-south. Often there are deviations, with the buildings stretching from northeast to southwest. When building the houses, the sun seemed to be aligned with the fact that the morning sun had to shine on the living spaces. Due to the fact that the construction activity was mainly in winter (outside the busy summer time), this resulted in a deviation in the orientation. A northwest-southeast orientation is very rarely found.

The rural property consists of at least three areas:

- Residential buildings

- Stables and feed storage (barn)

- Bakery with pork and chicken coop

The buildings can be separated or the house, feed storage and stables can be placed one behind the other as a longitudinal building. The residential building is usually located along the western border of the courtyard; in the case of separate buildings, the threshing floor and stables are also longitudinally along the eastern border. The bakery with the small animal stalls is usually located in the northeastern courtyard area. In the south-eastern Bresse there are a few properties that are built in an angular shape.

Residential buildings

Living room

The main room of the residential building was formed by la maison (in the south, le hutau in the north). This part of the house was regularly filled with raw or baked bricks, and the floor was made of tamped clay. It was the largest room and served as the center of life for the whole family, was heated, originally with a Saracen fireplace (cheminée sarrasine), later with an open fireplace (cheminée à hotte). This room was generally quite large, often the chimney alone was 4 x 4 m. There were beds in the corners, next to them simple boxes for personal items. A long, narrow oak table stood in the middle of the room under the ridge purlin from which the spoons and forks hung. On the narrow wall, behind the Saracen fireplace, stood the bench (archebanc), which was solemnly blessed when the house was moved into. The windows were small, at most they had wooden shutters , more rarely they were glazed. A little light also fell through the Saracen chimney, along with rain and snow. One corner of the room was reserved for the chapel , a kind of house altar, with a simple figure of Mary, a holy water stoup, one or two candles, images of saints and patriotic prints. The house altar was regularly whitewashed the evening before the parish fair.

Saracen fireplace (Cheminée sarrasine)

This peculiarity was an open fireplace of considerable size, which was heated in the middle of the fireplace. In addition, the chimneys above the roof were decorated with picturesque decorations. The living room was halved by the ridge purlin, and the fireplace was placed in one half of the room. A huge, inverted funnel that was attached to the ridge and central purlin served as a chimney. It also consisted of a wooden structure that was filled with clay and smeared. The chimney began in the living room, continued in a funnel shape to the roof, where it merged into the picturesque miter (chimney construction). The open fireplace was widespread throughout Europe in the Middle Ages and until the end of the 19th century and so far offers nothing special. The origin of the miter and the name Saracen are not clear, however, it is only common in the Bresse. Whether this construction method was actually used by the swaggering Saracens in the 8th – 12th It is not clear whether it was brought to the Bresse in the 19th century, or whether it is a component that was brought back from the Crusades. The term Saracen does not mean Christian and can be equated with the Latin barbarus .

Furnace chamber

In addition to the living room, there was regularly a second room, la chambre de poêle . The family lived there in winter, as the room was heated by the adjacent fireplace, but closed and had no chimney opening itself so that the cold penetrated it. If the family had servants and maids, the living room was reserved for them as a bedroom, while the foremen slept in the oven chamber. If the family had no employees, they often moved twice a year from the living room to the furnace chamber as a winter residence and to the living room as a summer apartment. Many simple Bresse houses only had these two rooms.

Girls room

If the house had several rooms, the girl's room joined the furnace chamber . Wall to wall with the parents, the care and parental supervision was maintained, especially since the girls' room was often only accessible via the stove room and had no external door of its own.

Servants' room

The servants and maids lived in the living room, but if the house was spacious and the family was wealthy, they were assigned a room next to the living room - opposite the girl's room.

Parents room

The grandparents 'room was in the servants' room, possibly in an annex or squeezed between the other utility rooms. This usage shows how high the esteem was for the old, no longer able to work family members of the simple peasant family.

Outbuildings

Basically, the Bressehaus includes the draw well , which, depending on the circumstances, can reach a depth of up to 25 m. The baking house is also an integral part of the Bressehaus . Depending on the prosperity, the Bressehaus is supplemented with outbuildings or parts of the building. These include sheds, chicken coops, pigeon houses or sheep and goat houses.

Stables

The stables either stand as a separate building parallel to the residential building, about 20 to 30 m away, in order to reduce the risk of fire. They are generally low and can have clay-coated twig infills or raw or baked clay brick infills. Hay and straw are stored under the large roof. In the south-east of the Bresse, the stables are often attached to the house at right angles and thus form an angular structure.

Bakehouse

The bakery is a separate building, often together with the pig and / or chicken coop. This allows the pig feed to be prepared in the bakery. The bakery consists - especially in the northern Bresse - of a double building: On the one hand the quite spacious bakery, directly attached to the oven in a somewhat lower annex. The chimney rises up between the two parts of the building.

Fountain

The well was always of great importance in the Bresse, which has few springs and potable surface water. In contrast, drinking water can be found relatively close below the surface almost everywhere. The well was usually covered, if necessary by the protruding canopy or by its own roof construction. Long balancing poles with counterweights were originally common in northern Bresse, but today the fountains are all equipped with cranks and chains.

Regional differences

Due to the historical division of the Bresse into the Bresse bourgignonne and the Bresse de l'Ain , the architectural styles of the farmhouses have developed differently. The border stretches from Cuisery south of Louhans , via Sagy to the Jura . The construction of the walls remains the same in and of itself, but there are differences in the shape of the roof. In the Bresse bourgignonne, the roofs are usually steep and high and covered with flat tiles , while the roof in the southern Bresse is flatter (<25% slope) and is covered with monk and nun . Older Bressans still remember that in their youth the majority of the fermes were thatched.

A characteristic of a Bresse house in northern Bresse is the roof decoration . Very often a "brick tower" or a gable flower is attached at the intersection of the roof ridge and roof ridge , but the ridge is often decorated in its entire length.

In the border area to the Jura , the house is often built from natural stone, mainly broken limestone , which can easily be obtained from the Jura. At least the corners of the house are partly built of stone to increase stability. In the area towards the Mâconnais and the Chalonnais , the courtyard becomes more closed and one often encounters four-sided courtyards enclosed by a wall. The street is reached through a portal.

In the swampy area of Bellevesvre and Beauvernois there were small, poor huts on stilts until the 1930s. These served the frog catchers as dwellings. Apparently the last of these houses was demolished in 1931.

Regional particularities

An old Bressan tradition allowed everyone in the municipality's own heathland, i.e. outside the settlement areas, to benefit from the property and the surrounding area if they built their house during one night. Migrants who wanted to settle down or the children of poor people who wanted to start their own household had this opportunity to become landowners overnight. During the winter days the wood was felled and prepared for construction, friends and comrades were asked for help and one day everything was neatly prepared. The construction was tackled preferably during a long winter full moon night and at the first crowing of the cocks a mistletoe adorned the ridge of the thatched roof. Often, however, the new owners of these maisons de la lune remained poor and needy, their houses were in forest clearings, in impassable terrain, far away from the municipal boundary. They tried to earn a living doing day labor, poaching or catching frogs , smuggled Marc , made matches, tried quackery or even witchcraft. The last house built in one night was built in 1902 in Mervans by Marie Chalumeau . The material was largely leftover wood from the construction of the station, which was just being built at the time.

Construction process

The arrangement, elements and peculiarities of the Bressehaus did not come about by chance; First of all, it was determined where the main building should be. Either stones were buried where the walls would later stand, or at least the thickest oak beams possible were laid out as a square. On this stone or wooden foundation sleepers and stands were placed and stabilized with bolts and swords. Finally the ceiling was pulled in and the attic was erected. At the same time, construction of the bakery began. Often stones were used for this, at least for the stove, the building was kept rather small. A hole was dug at the location of the future well in order to reach the clay layer as quickly as possible. The clay was extracted, pressed into bricks in molds that were baked in the bakery. After the completion of the wooden structure, it was filled in, in the best case with fired, at best with raw clay bricks. In the worst case, the infill was done with braided branches that were covered with clay. This construction method results in the structural elements that characterize the Bressehaus: the residential house in the frame construction, the well as a result of the clay extraction and future water supply and the bakery to burn the bricks.

swell

- G. Jeanton, A. Duraffour: L'Habitation paysanne en Bresse. 2nd Edition. Société des Amis des Arts et des Sciences de l'Arrondissement de Louhans, 1993.

Single receipts

- ^ Frontenard, 12 rue de la Motte (Base Mérimée des Ministère de la Culture)

- ^ Studies in Romenay and in the cantons of Saint-Germain-du-Bois and Pierre-de-Bresse, according to L'Habitation paysanne en Bresse. P. 39.

- ^ Base Mérimée des Ministère de la Culture

- ^ The buildings in the heathland, according to L'Habitation paysanne en Bresse. P. 38 + 43.

- ↑ Still visible in La Genête and La Chapelle-Thècle, according to L'Habitation paysanne en Bresse. P. 38.

- ↑ Michel Bouillot: L'habitat rural en Bresse bourgignonne. Publishing house Foyers Ruraux de Saône-et-Loire, ISBN 2-907497-06-5 .