British Mount Everest Expedition 1922

The British Mount Everest Expedition in 1922 was the first expedition specifically aimed at the first ascent of Mount Everest . After two failed ascent attempts, the expedition ended with a serious accident on the third attempt. This expedition was the first to use oxygen from pressurized cylinders as a climbing aid.

In the previous year, an exploration expedition had already penetrated the area of Mount Everest. Here was George Mallory , discovered one of his opinion viable route to the summit, which both participants exploring expedition and the expedition of 1922 was.

Preparations

Attempts to climb Mount Everest were among other things an expression of the pioneering spirit that reigned in the British Empire . After the British had been the first to reach neither the North nor the South Pole , their efforts were now directed towards conquering the so-called “Third Pole”, ie the first ascent of Mount Everest. First of all, Brigadier Cecil Rawling planned two expeditions in 1915 and 1916 , but these had to be postponed due to the First World War and the death of Rawling. The expeditions undertaken in the 1920s were then organized by the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club , mainly in the jointly formed Mount Everest Committee .

The surveying work in 1921 made it possible to create maps, which were then made available to the 1922 expedition. John Noel took on the task of putting together photographic equipment to document the expedition as best as possible. So were three film cameras , two panoramic cameras , four plate cameras , a stereo camera and five so-called pocket-Kodak ( Vest Pocket Kodak ) for equipment. The latter were photo cameras that were small and light enough that mountaineers could take them to great heights. The mountaineers should be able to document a possible summit success. A darkening tent was also taken to develop the photos. A large number of photos and a film are thanks to Noel.

During the expedition in 1921 it was recognized that the best time for an ascent was very likely the time of the pre-monsoon . The expeditions in 1922 and 1924 were planned according to this knowledge.

Bottled oxygen as a climbing aid

The year 1922 can also be seen as the starting year of the controversy that continues to this day about the use of bottled oxygen for mountain climbing at great heights. During the British Mount Everest Expedition in 1921, oxygen bottles were already with them, but they were not used. Alexander Mitchell Kellas, who was one of the first scientists ever to point out the useful use of bottled oxygen at high altitudes since around 1920, took part in the 1921 expedition, but died on the approach. However, because of the systems that were still very difficult at the time, he himself was skeptical as to whether they could be taken all the way to the top. Kellas' findings also received little attention, perhaps because he did research as a private person. The pressure chamber experiments of Professor Georges Dreyer , who was active as an altitude medical advisor to the Royal Air Force during World War I, received more attention . After his studies, which he carried out with George Ingle Finch , among others , he was of the opinion that survival at such great heights was only possible with oxygen-enriched breathing air. Furthermore, the observations of Paul Bert , who investigated the death of balloonists at high altitudes, were used. The fact that oxygen bottles were given in 1922 was a result of these investigations.

Such a bottle contained about 240 liters of oxygen. Four such bottles were attached to a frame that the mountaineers were supposed to carry on their backs. Together with other attachments, the total weight was around 14.5 kg. So every mountaineer would have had to carry a lot of extra weight at the beginning of the day. Ten of these systems were made available to the expedition. Although a mask has been pulled over the nose and mouth, a tube should also be kept in the mouth. Dreyer had also suggested the flow rate: at an altitude of 7000 m, 2 liters of oxygen should flow per minute, while on the climb to the summit it should flow 2.4 liters per minute. The result was that one bottle would have lasted about 2 hours. The entire oxygen supply would have been used up after 8 hours at the latest. Nowadays 3 or 4 liter bottles are mostly used, which are filled with oxygen at a pressure of 250 bar . At a flow rate of 2 liters per minute, a smaller modern bottle can be used for 6 hours.

George Finch was responsible for the devices on the trip, which was also due to his training as a chemist and his interest in this technology. He ordered daily exercises with the devices. The weaknesses quickly came to light: the equipment was very prone to failure, not very robust in the event of impacts and very heavy with a low content of oxygen. A dispute broke out among the expedition members about these devices; many climbers preferred to climb without them. The oxygen-enriched breathing air was referred to as "English air" by the porters .

Expedition participant

The expedition participants were not only selected for their mountaineering qualities. Class membership as well as membership in the military or certain professions played an important role. The military ranks or the university degrees of the individual expedition participants were particularly pointed out to the public.

| Surname | function | job |

|---|---|---|

| Charles G. Bruce (1866-1939) | Expedition leader | Soldier (officer, rank: Brigadier General ) |

| Edward Lisle Strutt (1874-1948) | Deputy expedition leader and mountaineer | Soldier (officer, rank: Lieutenant-Colonel ) |

| George Mallory (1886-1924) | climber | Teacher |

| George Ingle Finch (1888-1970) | climber | Researchers and teachers at Imperial College |

| Edward "Teddy" F. Norton (1884–1954) | climber | Soldier (officer, rank: major ) |

| Henry Treise Morshead (1882-1931) | climber | Soldier (officer, rank: major) |

| Dr. Theodor Howard Somervell (1890-1975) | climber | doctor |

| Dr. Arthur William Wakefield (1876-1949) | climber | doctor |

| John Noel (1890-1989) | Photographer and film cameraman | Soldier (officer, rank: captain ) |

| Dr. Tom George Longstaff (1875-1964) | Expedition doctor | doctor |

| John Geoffrey Bruce (the cousin of Charles G. Bruce) (1896–1972) | Interpreter and organizational tasks | Soldier (officer, rank: captain) |

| C. John Morris (1895-1980) | Interpreter and organizational tasks | Soldier (officer, rank: captain) |

| Colin Grant Crawford (1890-1959) | Interpreter and organizational tasks | Indian civil administration official |

In addition to the actual mountaineers, there was also a large group of porters, so that the expedition ultimately consisted of around 160 men.

getting there

The way to the base camp largely followed the route that was also taken in 1921. Darjiling , where the expedition participants gathered at the end of March 1922, served as the starting point in India . Some of the participants had already traveled there a month in advance to recruit porters and take care of other organizational matters. For most of the expedition members, the journey to Mount Everest began on March 26th. Crawford and Finch stayed behind to take over the transport of the oxygen bottles. These only reached Calcutta around the time when the expedition left Darjiling. The rest of the organization worked and the bottles were soon transported on.

The Dalai Lama Thubten Gyatsho had obtained permits for the trip through Tibet . From Darjiling, the route led via Kalimpong to Phari Dzong and on to Kampa Dzong , which was reached on April 11th. The group rested there for three days so Finch and Crawford could catch up with the oxygen bottles. Then it went on to Shekar Dzong , in order to first reach the Rongpu monastery from the north and then the place provided for the base camp. In order to better acclimatize and to keep warm in the prevailing cold, the participants of the expedition often alternated between horse riding and hiking. On May 1, 1922, the group reached the base camp on the edge of the Rongpu Glacier .

Planned ascent route

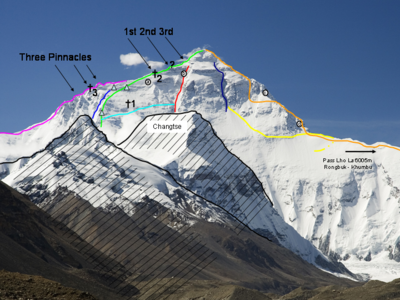

Before the Second World War, British expeditions could only access it from the north. Mallory discovered a passable route from Lhakpa La to the north side of the mountain and on to the summit in 1921 . This route begins at the Rongpu Glacier and then runs over the Eastern Rongpu Glacier, which flows into it, first to the North Col. From there, the exposed summit ridges (north ridge and northeast ridge) enable further ascent. A serious, exhausting and technically difficult obstacle is the middle of three rock steps in the northeast ridge, the second step at about 8,610 m, which was unknown before this expedition. It has a climbing height of about forty meters, the last five meters are almost vertical. From there, the ridge route leads to the summit with a relatively low incline, but the path is still quite long and before the summit snowfield, a third, around ten meter high step has to be climbed. Chinese mountaineers first managed to master this route in 1960. As an alternative to this, the British considered at that time to cross above the north saddle into the north flank of the mountain and climb the summit via a steep gorge, which was later called Norton-Couloir . Reinhold Messner first reached the summit via this route in 1980.

Attempts to climb

Starting from the base camp, the route over the Eastern Rongpu Glacier was still largely unknown. Therefore, starting May 5th, Strutt, Longstaff, Morshead and Norton undertook a first thorough investigation of the route. The advanced base camp (camp III) was built on the upper edge of the glacier, under the steep slopes of the north saddle, at an altitude of about 6350 m. Two further camps were set up between the base camp and the advanced base camp: Camp I at an altitude of about 5400 m and Camp II at 6000 m. The establishment and supply of these camps was supported by local farmers, who could only help for a short time because they had to till their fields. Longstaff spent himself building these camps, fell ill, and failed as a mountaineer for the rest of the expedition.

On May 10, Mallory and Somervell left base camp with the aim of setting up Camp IV on the North Col. They reached Camp III on May 15 and two days later dared to climb the North Col. The warehouse located there at an altitude of about 7000 meters was subsequently also supplied with supplies. The next plan was that Mallory and Somervell should first attempt an ascent without oxygen cylinders, followed by an attempt with oxygen cylinders from Finch and Norton. However, since most of the climbers fell ill, these plans were abandoned. The more or less healthy climbers Mallory, Somervell, Norton and Morshead should therefore try to climb the mountain together.

First attempt to climb

This first attempt at ascent was made by Mallory, Somervell, Norton and Morshead, supported by nine porters, without the use of supplemental oxygen from Camp III from May 19. They started the ascent to the North Col at around 8:45 a.m. The day was beautiful and sunny, according to Mallory. At around 1 p.m., they set up the tents. The following day, the climbers only wanted to take the bare essentials: two of the smallest tents, two double sleeping bags, food for a day and a half, a gas cooker and two thermos flasks. The porters were housed in tents in groups of three and were still completely fit at the time.

The following day, May 20, Mallory woke the group around 5 a.m. The porters survived the night poorly, as the tents hardly let any oxygen inside. Only five of them wanted to keep climbing. However, their condition quickly improved after they left the tents. Since the preparation of food also caused problems, the ascent was not continued until around 7 a.m. However, the weather that day was not as good as the day before. It was a lot colder. Above the north saddle they entered unknown terrain: never before had a climber climbed the top of the mountain. The porters accompanying them had no warm clothes and were getting more and more cold. As it was also very strenuous to cut steps in the hard snow , the plan to build a camp at an altitude of 8,200 m was abandoned. Instead, they set up a small camp at an altitude of 7600 m. Camp V. Somervell and Morshead were able to pitch their tent relatively straight, while Mallory and Norton had to pitch their tent on a sloping surface. The porters were now sent back down the mountain. That evening the mountaineers began to show signs of frostbite.

On May 21st, the four climbers left their sleeping bags around 6:30 a.m. and were ready to start at 8 a.m. During this preparatory phase, a rucksack with provisions fell down the mountain. Morshead, who suffered badly from the cold because he hadn't put on his warm clothes the day before, was able to get the backpack back. However, he was so exhausted afterwards that he could not continue the ascent attempt. The ascent from Mallory, Somervell and Norton was along the north ridge towards the northeast ridge. The conditions were again not ideal as a light blanket of snow covered the route. According to Mallory, it was not difficult to walk. Shortly after 2 p.m. the climbers decided to turn back. At this point they were about 150 m below the northeast ridge. The height of 8225 m they reached meant a new world record for mountaineers. They reached Morshead at the last camp at around 4 p.m. and then continued to climb down together. It was almost a serious accident when all the climbers except Mallory slipped. Mallory was able to secure it, however. The return to Camp IV was made difficult by the darkness of the night. On the morning of May 22nd, at around 6 a.m., they began the descent from the North Col.

Second attempt to climb

The second attempt to climb was carried out by George Ingle Finch, Geoffrey Bruce and Gurkha Tejbir with oxygen assistance. After Finch recovered, he found that there were no real mountaineers available besides himself. So he looked for others who, in his opinion, might be fit enough to climb. Bruce and Tejbir seemed the most likely to qualify. In the time before, the oxygen bottles had been transported to camp III so that enough bottles were available on the mountain. The three climbers reached this camp on May 20th, were able to test the oxygen bottles during the following days and found them to be good.

On May 24th, they climbed the North Col with Noel. From there, Finch, Bruce and Tejbir began the following day in moderate weather (it was very windy) around 8 o'clock with the ascent over the north ridge to the northeast ridge. Twelve porters carried the oxygen bottles and other material. It was again shown that the use of bottled oxygen had advantages: The three climbers were able to climb much faster than the porters despite their greater load. As the wind got stronger and stronger, they had to set up the camp at an altitude of 7460 m. The following day, May 26th, the weather continued to deteriorate and the group was unable to ascend any further.

The ascent could therefore only be continued on May 27th. At this point, however, the food supplies were almost exhausted, as a long stay had not been planned. Nevertheless, they set off around 6:30 a.m. The sun was shining, but the mountaineering was made more difficult by an increasing wind. Tejbir, who had no windproof clothing, soon slowed down and then collapsed to 7,925 m. Finch and Bruce sent him back to camp and continued their ascent to the northeast ridge, no longer roped up from now on. At an altitude of about 7,950 m, Finch changed the planned route because of the wind and dodged the north flank of the mountain in the direction of the steep gorge , later known as Norton-Couloir . They made good progress in the horizontal direction, but hardly gained any height. At about 8326 m above sea level, Bruce suddenly had a problem with the oxygen device. Finch noticed now that Bruce was very exhausted and they turned around. The altitude record was broken again during this attempt to climb. Around 4 p.m. the climbers reached camp on the north saddle and only an hour and a half later, camp III.

Third attempt to climb

According to the wishes of the expedition doctor Longstaff, there would not have been a third attempt at ascent: All the mountaineers were frostbitten or otherwise ill and also completely exhausted. But since the other doctors, Somervell and Wakefield, saw no great risk, the third attempt was made anyway.

On June 3, 1922, Mallory, Somervell, Finch, Wakefield and Crawford started with 14 porters at base camp. Finch had to give up at Camp I. The others arrived at Camp III on June 5 and spent a day there. Mallory was impressed by Finch's achievements - he had come higher than he himself and was also closer to the summit horizontally - and now wanted to take oxygen bottles with him as well.

On June 7 the porters were led above Camp III from Mallory, Somervell and Crawford through the flank of the North Col. The 17 men had formed 4 rope teams, with the European mountaineers all going in the first rope team and stepping on the trail. Halfway through, a slab suddenly came off. Mallory, Somervell and Crawford were only lightly buried and were able to escape quickly. The group behind them, however, was carried away about 30 m, while the other nine carriers of the remaining two rope teams fell into a crevice . Two of the porters were recovered alive and six others were recovered dead. One of the dead was not found. This accident meant the end of the expedition. All expedition participants were back in Darjiling on August 2nd.

After the expedition

After returning to England, Mallory and Finch went on a lecture tour and reported on the expedition. This trip had two goals: First, the interested public should be informed about the events and results, and secondly, another expedition was to be financed with the proceeds. Mallory also went on a three-month lecture tour in North America in 1923 . During this trip, Mallory was asked why he wanted to climb Mount Everest. Mallory's now famous answer was: "Because it is there" . The expedition to Mount Everest planned for 1923 had to be postponed for one year for financial and organizational reasons; among other things, the preparation time for a new expedition was too short.

The film Noel made during the expedition was also released. Climbing Mount Everest ran for ten weeks in the Philharmonic Hall in London and was a great success after a failed premiere and the subsequent addition of music.

The members of the expedition received the Prix olympique d'alpinisme at the 1924 Winter Olympics for their achievements . All 13 participants were personally awarded a gold-plated silver medal by Pierre de Coubertin .

In 2001 the former camp III was discovered at an altitude of about 6350 m . Three oxygen bottles, food cans, dry fuel stoves and batteries were found there. Furthermore, an oxygen bottle from the second attempt at ascent was recovered from the north ridge at an altitude of around 7570 m .

See also

- British Mount Everest Expedition 1924

- German-American Himalaya Expedition 1932

- German Nanga Parbat Expedition 1934

- German Nanga Parbat expedition in 1937 and the subsequent salvage expedition in 1937

- German Nanga Parbat Expedition 1938

- German Nanga Parbat Expedition 1939

swell

- ↑ a b Holzel, Salkeld: In the death zone

- ↑ a b c d e f g Breashers, Salkeld: Mallory's secret

- ↑ a b Report on the investigations by Dreyer and Finch

- ^ Information on the use of oxygen by H. Bielefeldt

- ↑ a b c d e The Geographical Journal, No. 6, 1922

- ^ The Geographical Journal, No. 2, 1922

- ↑ Die Naturwissenschaften, No. 5, 1923

- ^ Hazards of the Alps New York Times, March 18, 1923

- ^ Hemmleb, Jochen: Mount Everest crime scene: The Mallory case. Munich 2009

literature

- David Breashears, Audrey Salkeld: Mallory's Secret. What happened on Mount Everest? Steiger 2000, ISBN 3-89652-220-5 .

- Tom Holzel, Audrey Salkeld: In the death zone. The secret of George Mallory and the first ascent of Mount Everest. Goldmann 1999, ISBN 3-442-15076-0 .