British Mount Everest Expedition 1924

The British Mount Everest Expedition in 1924 was the second expedition, after the likewise British expedition in 1922 , with the express aim of the first ascent of the 8,848 meter high Mount Everest . A reconnaissance expedition had taken place in 1921. Because the Kingdom of Nepal was closed to foreigners, the British expeditions in the period before the Second World War were only allowed access from the Tibetan north side.

Three attempts were made during the expedition. The first failed early due to the cooperation of the porters, the second was canceled by Edward Norton due to the late time, but he reached a new record height for mountaineers at 8,573 m . Mountaineers George Mallory and Andrew "Sandy" Irvine disappeared on the third and final attempt at ascent . To this day there is speculation as to whether they had reached the summit. Mallory's body was found and identified in 1999.

Motivation and starting position

Britons participated in the races to reach the North Pole and the South Pole in the early 20th century but were unsuccessful. Since then, the first ascent of the highest mountain on earth has been discussed intensively under the motto "Conquering the Third Pole" and has also been linked to national prestige. The shame of being late at the geographical poles should be erased at the “Third Pole”. In addition, there were nationalist motifs, since Everest, due to the political presence of the British in Tibet , was viewed as a border summit of the British Empire.

The south side of the mountain, via which today's standard south route leads to the summit, was neither explored nor open to exploration: Nepal was considered a "Forbidden Land" for western foreigners. The route via the north side was also fraught with political problems: the Dalai Lama only allowed the British expeditionary activities after special efforts by British government representatives . Tibet was part of the " Great Game " for power, influence and economic priority that was being played across Central Asia by the great powers of that time, Russia and England .

A big handicap of all expeditions to the north side of Mount Everest was the narrow time window after the winter time before the onset of the monsoon rain . In order to get from Darjiling via Sikkim to Tibet from the Indo-English colonial empire , it was necessary to climb high passes east of the Kangchenjunga region that remained snow-covered for a long time . This first stage was followed by a lengthy journey through the Arun Valley to the Rongpu Valley on the north face of Everest. The expeditions transported by horses, donkeys and yaks did not reach the target region until late April; and in June the monsoon sets in.

Preparations

Before this 1924 expedition there were two others. All three expeditions were organized by the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club jointly through the Mount Everest Committee according to predominantly military principles, and also with the participation of the military.

The first expedition in 1921 focused on surveying the region around Mount Everest; the first ascent was not an express goal. During the stay there was also speculation about possible routes of ascent. At first the mountaineering director at the time, Harold Raeburn, believed he had discovered a viable route to the summit. It would have led over the entire northeast ridge. Mallory, who took part in all Mount Everest expeditions of the 1920s, later proposed a modified route that seemed easier to him. This led first over the north saddle and the north ridge and only then on the northeast ridge leading to the summit. After finding the eastern access to the north saddle, the entire route had been explored since 1921 and was essentially clear - it "only" had to be walked.

During the British Mount Everest Expedition in 1922 , several attempts were unsuccessfully made on the route proposed by Mallory. After their return, the preparation time and, above all, the financial means were no longer sufficient to send an expedition in 1923. This was mainly due to the bankruptcy of the Alliance Bank in Simla , in which the committee lost £ 700 . Therefore, the renewed attempt to climb was postponed to 1924.

Above all, the role of the porters was reconsidered in advance of the expedition. In 1922 it was found that they could carry their loads to greater heights than expected and thus could be included in the plan of the ascent much more.

oxygen

The Mount Everest Committee disagreed on whether bottled oxygen should be carried. In 1922 George Ingle Finch and Geoffrey Bruce had set a world record for mountaineering with bottled oxygen, but in retrospect their achievements were less recognized than those of Mallory, Norton and Somervell. These climbers were not that close to the summit, but they climbed without oxygen bottles. Bottled oxygen ascent was rejected by some as dishonorable.

Although the benefits were not really convinced, the expedition was equipped with bottled oxygen. In the two years between the expeditions, the oxygen devices had been technically improved, the decisive difference being in the capacity of the cylinders. Whereas in 1922 only 240 liters of oxygen could fit into a bottle, in 1924 it was 535 liters. The gross weight of the devices of around 15 kilograms could not be reduced, but the amount of oxygen was now more than twice as large.

Noel Odell was supposed to be in charge of the devices on this expedition. However, since Odell was still abroad when he left England, Irvine familiarized himself with the devices. Even before leaving, he had sent the manufacturer suggestions for improvement by letter, but these had not been taken into account. So Irvine set out in the course of the expedition to improve the devices themselves. His modified devices were probably much lighter and less susceptible to interference, but the oxygen cylinders often had defects and leaked. The unreliability of the devices, along with the discussion about the ethics of mountaineering, was the reason why there was no unanimous opinion on their use among the expedition members either.

Attendees

As two years earlier, Brigadier- General Charles G. Bruce was to be responsible for the management . He was responsible for the procurement of material, the recruitment of porters and the choice of the approach route.

In addition, the choice of mountaineers was difficult. During the First World War , a number of young men who would have been able to do this business had died. It was clear that Mallory should be there again, as well as Howard Somervell, Edward "Teddy" Norton and Geoffrey Bruce. George Ingle Finch's participation was controversial because of his class . Unlike other mountaineers, he did not seek proximity to the elite selection committee. His preference for bottled oxygen also met with criticism. The selection team did not think that you could only be successful with additional oxygen.

New to the team were Noel Odell, Bentley Beetham and John de Vere Hazard. Andrew Sandy Irvine, a mechanical engineering student whom Odell knew from an expedition to Spitsbergen , was something like the company's "experiment" and at the same time an attempt to bring "young blood" to Everest. Due to his technical understanding, Irvine was able to greatly improve the oxygen devices that were taken with them during the expedition, as mentioned, and to carry out many repairs.

The expedition participants were not selected based on their mountaineering qualities alone. Class membership as well as membership of the military and certain professions played an important role. The military ranks or university degrees of the individual expedition participants were highlighted for the public in particular.

In addition to a large number of porters, the expedition team consisted of the following people:

| Surname | function | job |

|---|---|---|

| Charles G. Bruce (1866-1939) | Expedition leader | Officer, rank: Brigadier |

| Edward F. Norton (1884-1954) | Deputy expedition leader and mountaineer | Officer, rank: Lieutenant-Colonel |

| George L. Mallory (1886-1924) | climber | Teacher |

| Bentley Beetham (1886–1963) | climber | Teacher |

| J. Geoffrey Bruce (1896–1972) | Mountaineer, responsible for the porters | Officer, rank: Captain |

| John de Vere Hazard (1885-1968) | Mountaineer, surveyor | engineer |

| Richard WG Hingston (1887–1966) | Expedition doctor, naturalist | Doctor and officer, rank: major |

| Andrew C. Irvine (1902-1924) | climber | engineer |

| John BL Noel (1890-1989) | Photographer, film cameraman | Officer, rank: Captain |

| Noel E. Odell (1890-1987) | climber | geologist |

| Edward O. Shebbeare (1884–1964) | Transport officer | Administrative officer in the Indian Ministry of Forestry |

| Dr. T. Howard Somervell (1890-1975) | climber | doctor |

getting there

Charles and Geoffrey Bruce, Norton and Shebbeare arrived in Darjeeling in late February 1924 . There they selected the porters from a number of Tibetans and Sherpas . In addition, like two years earlier, the native Tibetan Karma Paul was employed as interpreter and Gyalzen as sirdar (leader of the porters). The selection of equipment and food also went on steadily, so that at the end of March 1924, when all the expedition members had gathered, the approach to Mount Everest began. The route taken in 1921 and 1922 was largely followed. In order not to overcrowd the accommodations, they marched and spent the night in two groups. Yatung was reached in early April and Phari Dzong on April 5th. There were difficulties with the authorities there, which dragged on for two days. The main part of the expedition then hiked the familiar route towards Kampa Dzong , while Charles Bruce and a few others chose an easier but significantly longer route. On this way Bruce became so seriously ill with malaria that he could not continue to lead the expedition and handed it over to Norton, who was to carry out this task to the complete satisfaction of all. On April 23, the expedition arrived in Shekar Dzong ; on April 28, she reached Rongpu Monastery , just a few kilometers from the planned base camp . The lama of the monastery was sick and could neither greet the British nor bless the porters as he had done two years earlier. The following day they reached the base camp in front of the glacier tongue in the main Rongpu valley. After the weather was acceptable during the approach, it was very cold here and snow was falling.

Planned ascent route

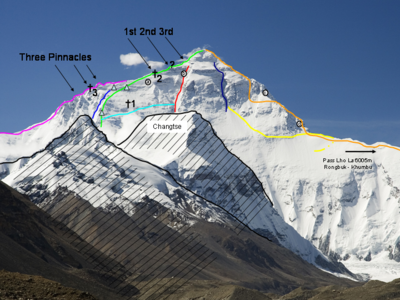

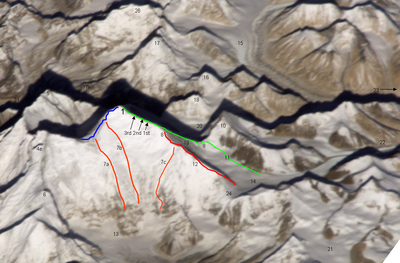

Mallory discovered a passable route from Lhakpa La to the north side of the mountain and on to the summit in 1921 . This route begins at the Rongpu Glacier and then runs over the Eastern Rongpu Glacier, which flows into it, first to the North Col. From there, the exposed summit ridges (north ridge and northeast ridge) enable further ascent. A serious, exhausting and technically difficult obstacle is the second rock step in the northeast ridge, the second step at about 8610 m , the difficulty of which was unknown before the expedition. Rather, the mountain above the north saddle was viewed as a simple rock mountain. The second step has a climbing height of about 40 meters, the last five meters are almost vertical. From there, the route, which mostly runs on the ridge, leads quite far and also over the snowfield at the summit, which is up to 50 degrees steep. Chinese mountaineers first managed to master this route in 1960. In contrast to this later first ascent, the British considered crossing above the north saddle into the north flank of the mountain and climbing the summit via a steep gorge, which was later called Norton-Couloir . Reinhold Messner first reached the summit via this route in 1980.

Building the camp

The positions of the first high camps had been planned before the expedition. Camp I was set up at about 5500 m at the confluence of the Eastern Rongpu Glacier with the main arm. Camp II was set up halfway to the steep slopes of the north saddle at about 5900 m . The advanced base camp (also called camp III) was set up at 6,400 m directly below the icy steep slope . The equipment was mainly transported from the base camp to the high camps by around 150 newly recruited porters. They received about one shilling a day for their work . However, many of the porters disappeared after a short time because they had to work in their fields. At the end of April 1924 work began on camps I to III. Contrary to expectations, the expedition got into an extremely bad weather phase, which forced a dramatic and sometimes chaotic retreat between May 5th and 11th. There were two fatalities and several injured.

On May 15th, the expedition participants, consciously requested by Norton on May 13th, received the blessing of Dzatrul Rinpoche in Rongpu Monastery, who especially motivated the Bhotia and Sherpa high porters. From now on the weather also improved; Norton, Mallory, Somervell, and Odell arrived at Camp III on May 19th. Only one day later they began securing the ascent to the North Col, but returned to Camp III that evening. Camp IV was finally set up on May 21 on the north saddle (about 7000 m ).

During the following days, the weather deteriorated again. Hazard was left in Camp IV with twelve porters and little food. He later managed to descend with eight porters. The remaining four porters became afraid and, after initially following Hazard, returned to Camp IV. There was hardly any food left there, however, and snowfalls were expected. The four porters were subsequently rescued by Norton, Mallory and Somervell, although these three were all sick themselves. The porters had frostbite throughout. Somervell and Mallory wanted to prevent another catastrophe like 1922.

On May 26th, the leader gathered the entire team in Camp I for a long “council of war” during which the team revised the original plans. The prerequisite for this was the availability of 15 other porters who had remained physically fit. This elite group was given the name “the tigers”.

Attempts to climb

Mallory and Bruce made the first attempt at ascent. After that, Somervell and Norton got a chance. Odell and Irvine supported the first two summit teams from Camp IV, Hazard from Camp III. The supporters were the reserve for a third attempt at ascent. Bottled oxygen was waived on the first and second ascent attempts.

The first attempt to climb

On June 1, 1924, Mallory and Bruce, supported by nine porters, began the further ascent from the North Col. Camp IV was relatively sheltered from the wind 50 meters below the north saddle edge; when the two left the shelter, they were exposed to very strong winds. Before Camp V could be erected at about 7700 m , four girders had deposited their loads. While Mallory was setting up the platforms for the tents, Bruce and a porter had to fetch these deposited loads. The following day three other porters refused to continue the climb; the attempt to climb was canceled without having set up camp VI. Halfway to Camp IV, they met Norton and Somervell, who were just beginning their second attempt at ascent.

The second attempt to climb

The second attempt to climb was made on June 2nd by Norton and Somervell with the support of six porters. They were amazed to see Mallory and Bruce dismount so quickly, and worried that their porters would not climb out of Camp V either. This concern should prove unfounded. So in the evening two porters were sent back to Camp IV, while the remaining four porters lay down in one tent and the two British in another. The following day three porters were ready to carry their loads further up the mountain. Camp VI was set up in a small rock niche at about 8,140 m . Now the porters have been sent back to the North Col. On June 4th, the mountaineers could not set off until 6:40 a.m. because a thermos bottle with drinking water had leaked and new snow had to be melted first. The weather seemed ideal. After about 200 meters of altitude traversing the north face, however, both of them became so constricted that they had to take many breaks.

Somervell could not climb any further by noon; Norton went on alone. He did not aim for the northeast ridge, but stayed well below the ridge height and crossed into the north face in the direction of a steep gorge that extends to the eastern foot of the summit pyramid. This steep gorge has been called Norton Couloir ever since. Somervell took one of the most famous photos of the expedition: It shows Norton how he carefully climbed steep slabs covered in fresh snow at an altitude of 8573 m . Until 1952 , no climber could prove to have reached a greater height. The easier slopes of the summit pyramid were only 60 meters above him when he decided to turn back. He justified this with the lack of time and doubts about one's own performance. He reached Somervell about 2 p.m. they continued to descend together. Somervell walked behind Norton. He had already given up on himself when he sat on the floor and was threatened with suffocating from a plug of mucus in his windpipe. In one last desperate attempt, he pressed his upper body together with his arms and finally managed to loosen the plug. Shortly afterwards he was feeling a lot better.

It was dark below Camp V, but they reached Camp IV. Here they were brought oxygen bottles, which they refused. Instead, they asked for drinks. That night, Mallory Norton announced his plan to try oxygen cylinders. Norton struggled with snow blindness for the following days .

The third attempt to climb

Mallory and Bruce had descended into Camp III during the attempt to climb Somervell and Norton and climbed again with oxygen bottles. Mallory chose Irvine to accompany him on the third attempt. Mallory's choice for Irvine was probably less his mountaineering qualities than his knowledge of oxygen equipment. In addition, Mallory and Irvine had made friends during the journey.

The climbers spent June 5th in Camp IV. At 8:40 am the following day, Mallory and Irvine, along with eight porters, set out for Camp V, where they sent four porters down again. On June 7th they reached Camp VI. Meanwhile, Odell went with a porter to Camp V. Shortly after his arrival there, the remaining four porters from Mallory and Irvine arrived at Camp V; Mallory had sent them down. Among other things, they handed Odell a message from Mallory to John Noel .

- Dear Noel,

- we will probably leave very early tomorrow (on the 8th) to have clear weather. It won't be too early to look out for us at 8pm, either as we cross the ledge under the summit pyramid or as we climb the ridge.

- your

- G Mallory

Mallory didn't mean 8 pm (in the evening), but 8 am (in the morning).

Odell set out on the morning of June 8th to reach a good vantage point. The mountain around him was shrouded in clouds, so he couldn't see Mallory and Irvine. He was mainly responsible for geological research and wanted to help the others with their descent when the opportunity arose. He climbed a rock spike at about 7,900 m . There the fog broke up briefly around 12:50 p.m. Odell noted in his diary that he "saw M & I on the ridge walking to the base of the summit pyramid". In a first message to the Times on July 5, he described this in more detail. Accordingly, he saw the entire summit, ridge and summit pyramid of Everest. His “eyes caught a tiny black point, which stood out as a silhouette on a small edge of firn under a rock step in the ridge, and the point moved. A second black point moved up to the other on the ridge. The first then approached the great rock step and in an instant appeared at the top; the second followed ”. Odell said at first that he saw both climbers on the second step.

Odell was concerned at the time of the observation, however, because both were significantly behind schedule. After the observation, Odell went up to Camp VI, where he found great chaos. Clothes, food, oxygen bottles and parts of the associated equipment were scattered around the tent. After a short stay he climbed a little higher and tried to draw attention to himself by shouting and whistling in the onset of the snowstorm and to make the descent easier for the mountaineers. When Odell came back to Camp VI, the snow stopped falling. He searched the mountain for Mallory and Irvine, but couldn't see them.

Since Mallory wanted to dismount quickly and there was only room for two people in Camp VI, he had instructed Odell to return to Camp IV by evening, which he reached around 6:45 p.m. On June 9, Odell made his way up again with two porters, as no sign of Mallory or Irvine had yet been discovered. At around 3:30 p.m., they arrived at Camp V, where they spent the night. The following day Odell went to Camp VI alone and found it unchanged. Then he probably climbed up to 8,300 m , but even from there he could not find any trace of the missing climbers. In camp VI he laid out two sleeping bags in the shape of a "T", which was the agreed-upon sign for no trace to be found; Hope was given up to the expedition members waiting further down the mountain. Then Odell descended to Camp IV. On the morning of June 11th, the descent from the north saddle began and the expedition ended. Five days later, the climbers said goodbye to the Lama of Rongpu Monastery.

After the expedition

The remaining expedition participants erected a memorial pyramid in honor of the people who died on Mount Everest in the 1920s. Mallory and Irvine became national heroes after their death. The University of Oxford , where Irvine studied, dedicated a memorial stone to him. In St Paul's Cathedral of was in the presence of the king and other nobles and long-time companion, a memorial service held. It was not until 1933 that another expedition was sent - above all, the presentation of John Noel's expedition film, The Epic of Everest , in Europe and North America, with specially bought dancing Tibetan lamas in the program, not only angered the Dalai Lama, but also internally put in a difficult position.

Odell's sighting

After the expedition, Odell thought it very likely that Mallory and Irvine had reached the summit of Mount Everest. The basis for this assessment was the location at which he had seen the two black points and his assessment of the climbers. It should be noted that Odell varied the place where he wanted to see her again and again. Immediately after the expedition, he was of the opinion that he had seen the climbers at the foot of the summit pyramid, i.e. between the second and third step. The last stage is not a serious obstacle for climbers because it can be easily avoided. In the expedition report he writes that the climbers were at the last step under the summit pyramid, which indicates the second step (the third step was not yet known in the Mount Everest nomenclature at this point). Later he also thought it possible that he had seen the climbers on the First Step . Furthermore, his information on the weather situation was fluctuating. So Odell describes first that he could see the whole summit, later that only part of the summit ridge was free of fog. When Odell saw a photo of the expedition in 1933, he said again that he could have seen them on Second Step . In 1986, he admitted he hadn't really been sure since then which stage he'd seen Mallory and Irvine at.

Finds

The first significant finds that can provide information about the whereabouts of Mallory and Irvine, Odell made in camps V and VI. In Camp V he found Mallory's compass , which was actually considered to be indispensable. He also discovered several oxygen bottles and accessories, so that at first he wasn't sure whether the two missing climbers had even carried oxygen bottles with them. This suggests that there was a problem with these bottles in the camp that Irvine tried to fix, or that both were using the oxygen to sleep. An electric flashlight also remained in the tent - it was still working nine years later when the 1933 expedition came across the remains of the tent.

Harris and Wager, participants in the British Mount Everest expedition in 1933, found the Irvine ice ax about 230 meters east of the First Step and 20 meters below the ridge while attempting to climb it . The location is still a mystery today. The terrain there is not so difficult that you would have to assume a fall, but no climber on Mount Everest would voluntarily put his ice ax there.

During the first ascent of the mountain via the northern route in 1960, the Chinese mountaineer Xu Jing discovered a dead man in the Yellow Band , a ledge made of yellowish rock. Chhiring Dorje described the discovery of an old dead man in a similar way. According to current knowledge, this corpse could only have been Irvine. During the second ascent of the mountain via the north route in 1975, the Chinese climber Wang Hongbao discovered an English dead person at 8100 m . Although this news was never officially released, this description was the starting point for the first Mallory and Irvine search expedition in 1986, which, however, took place under poor weather conditions in the post-monsoon and brought no results. In 1999 another search expedition was undertaken. It was directed by Eric Simonson, who claims to have seen some very old oxygen bottles not far from the First Step in 1991. One of these bottles was found in 1999 and could be assigned to Mallory and Irvine. Attempts were also made to take Odell's position when he was last watching Mallory and Irvine. Mountaineer Andy Politz later described that all three levels were easy to distinguish. The most significant discovery of that year was the discovery of Mallory's body at an altitude of 8155 m . The condition of the corpse suggests that it did not fall very far. A fall from the ridge is therefore unlikely, rather the yellow ribbon can be assumed as the place of the accident. The corpse itself lies on an only slightly inclined rubble belt to this day. The location of Irvine's ice ax cannot be directly linked to the location of Mallory's corpse, as his injuries are not severe enough. It seems certain that Mallory fell and slipped a little. The injuries suffered in the process were sufficient to make a descent impossible (head injury and one leg was broken), but he was probably still conscious after the fall. There is hardly any other explanation for the leg-friendly posture in which he was found. Mallory was not wearing snow goggles at the time of death. The picture of his wife that he wanted to take down on the summit was no longer in his pocket in 1999. Since the camera was also missing, it cannot be said how high it got. A broken rope was tied around his body.

During the most recent search expedition in 2001, a glove was found, which probably also came from one of the two missing mountaineers. It was located near the ridge at 8,440 m above sea level and could have been placed there as a marker, as a descent to the north saddle is possible here. Furthermore, the last high camp of Mallory and Irvine was found at about 8140 m altitude.

In 1981, the American climber Sue Gillner found a piece of metal with a kind of strap on the Kangshung wall . According to her, this could have been part of an old cradle for the oxygen devices.

Assumptions about the possible summit success

To this day there are speculations that Mallory and Irvine could have made it to the summit of Mount Everest and that they would be the first to climb the mountain. An important question is whether the clothing of the two climbers was suitable for the summit. In 2000, Spanish mountaineers made reproductions of the original clothing up to an altitude of 8,550 m . Six years later, the television producer Graham Hoyland came to the advanced base camp at 6400 m in a reproduction of the original clothing . It is often falsely stated that he reached the top in clothing, which consisted of layers of sheep's wool, cotton and silk under a gabardine jacket. Mallory's clothing, made from the original materials, has already been tested for windproofness and insulation using modern test methods. It corresponds roughly to a layer of modern thermal underwear under two layers of fleece and an overalls made of Gore-Tex - sufficient for the summit in good conditions, but not for an emergency bivouac or heavy snowfall.

Odell's sighting in particular has received a lot of attention to this day. The description of Odell and today's knowledge make the Second Step as a site of sighting seem unlikely. This one cannot be climbed in such a short time as described by Odell. Only the first step and the third step known today can be climbed in such a short time. What speaks against the First Step is that Odell described it in his first description as climbing just below the summit pyramid. The first step is very far from this; confusion is hardly possible. However, the third step also seems unlikely, because reaching it would have required a much earlier start-up time than planned. Nevertheless, in the recent past theories have repeatedly been put forward as to whether and how Mallory and Irvine could have climbed the Second Step . Oscar Cadiach was the first to climb the step in 1985. He rated the final wall with a V + and thus within Mallory's ability. Theo Fritsche confirmed this assessment after his ascent in 2001. Conrad Anker had the ladder, which had been attached to the step since 1975, removed in 2007 in order to climb this step without their help. Leo Houlding climbed in the ascent and rated it VI. Both reached the summit with almost the same equipment (e.g. cotton rope) and clothing that Mallory and Irvine had at their disposal.

The subject of many theories about Mallory's possible summit success is that he could have separated from his young partner. Irvine Mallory could have helped overcome this with a shoulder stand on the second step. Above the step, Mallory could have reached the summit alone. In exchange, until Mallory's body was found, the English corpse spotted by Wang Hongbao, who was supposed to be Irvine, spoke. According to these theories, he should have died while waiting for Mallory. However, many attest Mallory a sufficient level of mountaineering ethics and cannot imagine that a gentleman like Mallory would leave his protégé alone. The broken rope tied around Mallory's body suggests that both climbers were roped up at the time of the accident, meaning that they had not separated beforehand.

Against the assumption that the summit has been reached, the fact that, viewed from below, the path appears much shorter than it actually is, and so you could hardly have been to the summit before dark. It was not until 1990 that Edmund Viesturs was able to reach the summit from a point as distant as Mallory and Irvine intended. But Viesturs knew the way, while Mallory and Irvine walked in completely unknown territory. Moreover, Irvine was not an experienced mountaineer, but a beginner, and it does not seem plausible that Mallory would have put his new friend in such danger and climbed to the summit without thinking about a safe return. How and under what circumstances both climbers died has not yet been clarified.

Today's bidder on essentially the same route set off from the last high camp at 8200 m at midnight because of the very long way there and back and to avoid a second night with a bivouac when descending ; they use the light of electric headlamps until dawn on the ascent - a technology that was not available to the English at the time.

Almost 30 years later, the first climbers Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary found no traces on the summit that could have indicated an earlier ascent.

literature

- David Breashears , Audrey Salkeld: Mallory's Secret. What happened on Mount Everest? . Steiger, Munich 2000 (Original title: Last climb. The Legendary Everest Expeditions of George Mallory ), ISBN 3-89652-220-5 .

- Jochen Hemmleb: Mount Everest crime scene: The Mallory case - New facts and backgrounds . Herbig, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-7243-1022-8 .

- Jochen Hemmleb, Larry A. Johnson, Eric R. Simonson: The Spirits of Mount Everest . Frederking and Thaler, Munich 2001 (original title: Ghosts of Everest - The Search for Mallory & Irvine ), ISBN 3-89405-108-6 .

- Jochen Hemmleb, Eric R. Simonson: Detectives on Everest. The Story of the 2001 Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition . The Mountaineers Books, Seattle 2002, ISBN 0-89886-871-8

- Tom Holzel, Audrey Salkeld: In the death zone. The secret of George Mallory and the first ascent of Mount Everest . Goldmann, Munich 1999 (Original title: The Mystery of Mallory & Irvine ), ISBN 3-442-15076-0 .

- Edward Felix Norton et al. a .: To the top of Mount Everest - the ascent in 1924 . Sport Verlag, Berlin 2000 (Original title: The Fight for Everest ) ISBN 3-328-00872-1 .

Movies

- The Wildest Dream - Conquest of Everest. Docudrama , USA, 2010, 94 min., Director: Anthony Geffen, script: Mark Halliley, actors: Conrad Anker , Hugh Dancy , Ralph Fiennes , ( The Wildest Dream in the Internet Movie Database ).

- The first on Mount Everest? Documentary, docudrama, France, Germany, PR China, 2011, 52 min., Directors: Frédéric Lossignol, Gerald Salmina, production: arte France, MC4, ORF Universum, WDR , pre tv, Taglicht Media , first broadcast: January 22, 2011, Synopsis of arte.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Holzel, Salkeld: In the death zone. Pages 57-58

- ↑ Holzel, Salkeld: In the death zone. Pages 62-63

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, pp. 66-74

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, pp. 115-119

- ↑ a b c d e f g The Geographical Journal, No. 6 1924

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, 116

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, 105

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, 149

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's secret

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, page 120

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, pp. 120-121

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, pp. 124-129

- ↑ Route statistics for Mount Everest, www.8000ers.com

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, pp. 143-150

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, pp. 154-157

- ↑ a b Holzel, Salkeld: In the death zone

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, 173

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, 174

- ^ Norton: To the top of Mount Everest, p. 124

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, 199

- ↑ Holzel, Salkeld: In the death zone, page 363–364

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, 204

- ^ The Geographical Journal, Dec. 1924, p. 462

- ^ The Geographical Journal, December 1924, pp. 467/468

- ^ Norton: To the top of Mount Everest, pages 124/125

- ↑ The Geographical Journal, December 1924, pages 458-460

- ↑ Breashears, Salkeld: Mallory's Secret, pp. 201-204

- ↑ J. Hemmleb, E. Simonson: Detectives on Everest, pages 181-188

- ↑ a b c d J. Hemmleb: Mount Everest crime scene: The Mallory case

- ↑ J. Hemmleb: Tatort Mount Everest: The Mallory case, page 123

- ↑ Holzel, Salkeld: In der Todeszone, pages 430-432