Cades Cove

Cades Cove is an isolated valley in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee , USA . The valley was originally densely populated and was abandoned after the creation of the national park. Today Cades Cove is the most popular tourist destination within the park, about two million a year. Attracts visitors. The main attractions are the well-preserved settlements, the romantic mountains and the diverse fauna. The Cades Cove Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places .

geology

Geologically speaking, Cades Cove is a geological window over a layer of limestone that was created by the erosion of an older, Precambrian sandstone. More erosion-resistant rocks, such as the Cades sandstones at Rich Mountain to the north and the Elkmont and Thunderhead sandstones at Smokies Crest to the south, enclose the cove, making it relatively isolated in the Great Smoky Mountains . As with the neighboring windows of Tuckaleechee Cove to the north and Wear Cove to the east, the weathering of the limestone created a deep, fertile soil that made Cades Cove attractive to farmers.

The main part of the rocks in Cades Cove are non-metamorphic sediments , which in the period between 340 mio. and 570 mio. Years during the ordovician . The Precambrian rocks that make up the surrounding mountain ridges are among the sandstones of the Ocoee Supergroup , which were built about 1 miard ago. Years ago. The mountains themselves were about 200 mio. up to 400 million During the years Alleghanian orogeny formed when Laurussia and Gondwana collided and thrusts of the older rock formations created over the younger ones.

Gregory's Cave

The cracking and weathering of sandstone and limestone has resulted in the formation of several caves in the area around Cades Cove. The two largest of these are Gregory's Cave and Bull Cave . Bull Cave is the deepest cave in Tennessee at 924 feet (281 m). Trilobite and brachiopod fossils have been found in Gregory's Cave.

The entrance to Gregory's Cave is approximately 3 m wide and 1.2 m high (10 × 4 ft ). The cave consists mainly of one large passage averaging 6–17 m wide and 4.6 m high (20–55: 15 ft). This passage is 133 m long and has a side cave that branches off to the right (S) approx. 91 m from the entrance and is accessible for approx. 30 m. In the vicinity of the sinus there are “talley marks” (measuring marks) on the wall, which were made by saltpeter miners and you can see that the soil on this side of the cave was excavated. Impacts of the pickaxes are still visible today. Saltpetre mining was practiced from the late 18th century until after the Civil War . So these digs were carried out sometime between 1818 and 1865 when the first settlers arrived at Cades Cove.

Gregory's Cave is the only cave in the national park that has been expanded as a show cave . The cave was opened to the public in July 1925. After the Gregory family's estate was bought for the national park in 1935, the family received a lifetime dowry and the owner's wife, JJ Gregory, Elvira, received lifelong residence until her death on March 26, 1943 One of her sons was allowed to stay in the country until he had harvested its fruit in the autumn.

Donald K. MacKay, a National Park Service geologist, reports that the Gregory family gave tours of the cave until 1935. The price of admission at the time was 50 cents for adults; Children were given free access.

During this use, there were laid out paths, some with wooden planks, and electric lights. Wesley Herman Gregory , the son of JJ Gregory, talks about a "Delco system"

During the Cold War was Gregory's Cave as atomic bomb shelter (fallout shelter) decorated with allocated capacity of 1,000 people. The cave was provided with food, water and other emergency supplies.

Gregory's Cave is now closed and only accessible with the permission of the National Park Service, primarily to researchers.

history

Early history

Until the 18th century, the Cherokee used two main routes to cross the Smokies from North Carolina to Tennessee on their way to the Overhill settlements . One of these trails was the Indian Gap Trail , which connected the Rutherford Indian Trace in the Great Balsam Mountains with the Great Indian Warpath in what is now Sevier County . The other was a deeper path that had its apex at Ekaneetlee Gap , a ridge just east of Gregory Bald . This trail passed through Cades Cove and Tuckaleechee Cove before continuing along the trails of Great Tellico and other overhill towns along the Little Tennessee River . European traders used these paths as early as 1740.

Around 1797, and probably earlier, Cherokee had established a settlement in Cades Cove, " Tsiya'hi " ( Eng .: Otter Place). This village, a better hunting camp, was somewhere on the plains of Cove Creek. Henry Timberlake , an early explorer in eastern Tennessee, reports that otters were abundant in the rivers in this area , although the otters were already extinct by the time the first European settlers arrived.

Cades Cove got its name from the chief of Tsiya'hi "Chief Kade". Little is known about him; only its existence was attested by a European trader by the name of Peter Snider (1776-1867) who lived in the nearby Tuckaleechee Cove. Abrams Creek , a creek that runs through the cove, was named after another chief, Abraham of Chilhowee .

In 1819, the Treaty of Calhoun ended all Cherokee claims to territory in the Smokies, and Tsiya'hi was abandoned soon after. However, the Cherokee continued to occasionally reside in the surrounding forests and attacked the settlers from time to time until 1838. They were then relocated to the Oklahoma Territories ( Path of Tears ).

European settlement

John Oliver (1793–1863), a veteran of the British-American War of 1812, and his wife Lurena Frazier (1795–1888) were the first European settlers to live permanently in Cades Cove. The Olivers originally came from Carter County , Tennessee. They arrived in 1818 in the company of Joshua Jobe , who had convinced them to settle in the Cove. However, Jobe returned to Carter County. The Olivers stayed, fought their way through the winter, and survived by feeding on dried pumpkin given to them by friendly Cherokee. Jobe returned with a herd of cows in the spring of 1819 and gave the Olivers two dairy cows to ease their complaints.

1821 bought William Tipton (Fighting Billy, 1761-1849), a veteran of the American Revolution and John Tipton , an opponent of the State of Franklin , large areas of Cades Cove, which he then sold to his sons and relatives, whereupon the Settlement experienced a real boom. In the 1820s, Peter Cable , a farmer of German origin, arrived in Cades Cove and built an elaborate system of dams and sluices through which the marshland in the western part of the cove could be drained. In 1827 Daniel Davis Foute opened a forge (Bloomery Forge) to manufacture metal tools. Robert Shields arrived in 1835 and built a tub mill on Forge Creek . His son, Frederick, built the first flour mill. Other early settlers built houses on the surrounding mountains; among others Russell Gregory (1795–1864), after whom Gregory Bald is named, and James Spence , after whom Spence Field is named.

Between 1820 and 1850, the population of Cades Cove grew to 671 and the size of the farms ranged from 150 to 300 acres (0.6 and 1.2 km²). However, the settlers were partially dependent on the settlement in nearby Tuckaleechee Cove for supplies and other goods.

A post office was set up in 1833, and Post Master Philip Seaton of Sevierville set up a weekly mail route in 1839. Telephones existed as early as the 1890s when Dan Lawson and several neighbors built a telephone line to Maryville . In the 1850s, several roads connected Cades Cove to Tuckaleechee and Montvale Springs , some of which are still maintained as forest and hiking trails.

religion

Religion has been an important part of life in Cades Cove from the very beginning, ever since the settlement of John and Lucretia (Lurena) Oliver. The Oliver managed to found an offshoot of Miller's Cove Baptist Church in Cades Cove in 1825 . After briefly joining the Wear's Cove Baptist Church , the Cades Cove Baptist Church was recognized as an independent congregation in 1829.

In the 1830s there was a church split in eastern Tennessee known as the "anti-mission split". The split arose over disagreements on the biblical basis of mission and other "innovations of the day". This debate reached Cades Cove Baptist Church in 1839 and was so emotional that the Tennessee Association of United Baptists had to intervene. Eventually thirteen members left the ward and formed Cades Cove Missionary Baptist Church that year, and the remaining ward changed its name to Primitive Baptist Church in 1841 . These Primitive Baptists believe in a strict, literal interpretation of Scripture . William Howell Oliver (1857–1940), pastor of the Primitive Baptist Church from 1882 to 1940, stated:

“We believe that Jesus Christ himself instituted the Church, that it was perfect in the beginning, suitable in its organization for every age of the world, for every place on earth, for every kind and state of the world, for every kind and state of the Humanity without any changes or changes that had to adapt to the times, customs, situations or places. "

The Primitive Baptists remained the predominant religious and political force in the Cove. The meetings were only interrupted by the Civil War . The Missionary Baptists, with a much smaller congregation, came together intermittently until the 19th century.

The Cades Cove Methodist Church was established in the 1820s, likely through the work of circuit riders like George Eakin . The Methodist community remained small.

Civil war time

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, Blount County , Tennessee, was a playground for abolitionist activity. The Manumission Society of Tennessee was active in the county as early as 1815 and the Quakers - whose group in Blount was quite large at the time - were so vehemently against slavery that, despite their pacifist attitude, they sided with the Union army fight. The founder of the Maryville College , Isaac L. Anderson , was a keen supporter of the abolitionist and often preached in Cades Cove. The doctor Calvin Post (1803-1873) from Blount probably had a base of the Underground Railroad (escape network) in the area of the Cove in the years before the war. With this in mind, it is not surprising that Cades Cove was clearly on the side of the Union, regardless of the destruction it suffered in the course of the war. There were few exceptions like the wealthy entrepreneur Daniel Davis Foute .

In 1863 began a time when Confederate Bushwhackers from Hazel Creek and other parts of North Carolina were systematically raiding Cades Cove, robbing pets and killing every Union supporter they could find. Elijah Oliver (1829-1905), a son of John Oliver and a sympathizer of the Union, had to hide at Rich Mountain for most of the war. Calvin Post was also in hiding and after the death of John Oliver in 1863 the Cove had lost its original guides.

Although the Federal Forces (Union Forces) captured Knoxville in 1863, Confederate raids continued. A crucial role in this period was played by Russell Gregory , who had originally sworn to remain neutral after his son had switched to the Confederate side. Gregory organized a small militia composed mostly of the older men from the Cove, and in 1864 they lured a band of Confederate marauders at the confluence of Forge Creek and Abrams Creek. The Confederates were overwhelmed and chased back to North Carolina by the Smokies. Though this largely ended the raids, a band of Confederates managed to return just two weeks later and kill Gregory.

Cades Cove suffered from the aftermath of the Civil War throughout the 19th century. It was not until 1900 that the population returned to the level it was before the war. The farms were no longer productive and the residents were wary of changes. The economy only slowly recovered during the Progressive Era (1890–1920).

Moonshining and Prohibition

The Chestnut Flats Area of Cades Cove, at the foot of Gregory Bald, was known for high quality corn brandy. Among the better-known black burners (moonshining) belonged Josiah Gregory ( "Joe Banty" 1870-1933), the son of Matilda Shields ( "Aunt Tildy") from his first marriage. The Primitive Baptists, first and foremost William Oliver and his son, John W. Oliver (1878-1966), were ardent opponents of both alcohol consumption and distilling, and the illicit distillery remained limited to the area of Chestnut Flats. John W. Oliver, who was the mail carrier at the time, often discovered illegal distilleries and reported them to the authorities. Oliver later described the image of the moonshiner as part of the hillbilly stereotype (mountaineer):

"All these public outlaws, and who were never recognized as real, loyal Mountaineers or real American citizens, by the upright people in the mountains."

In 1921, Josiah Gregory's Distille was dug up by the Blount County Sheriff. Even though it was later revealed that the tip came from a surveyor, the Gregorys blamed the Olivers. The night after the raid, William and John W. Oliver's barns were burned, causing much of the food and tools to be lost. Shortly thereafter, Gregory's son was attacked by Asa and John Sparks after a failed prank. In return, Gregory and his brother, Dana, hunted and shot the Sparks brothers on Christmas Eve 1921. Both brothers of the Gregorys were convicted of arson and later of criminal assault. However, they were pardoned after just six months and personally escorted home by Governor Austin Peay .

Gregory's Cave mentioned above likely played a role in moonshining as well.

National Park

Of all the communities in Smoky Mountain, residents of Cades Cove made the greatest opposition to the formation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The residents of the cove were initially assured that their land would not be included in the park area, whereupon they welcomed the establishment. But by 1927, times had changed, and when the Tennessee General Assembly passed a law granting funds to purchase land for the national park, the Park Commission also obtained permission to expropriate land within the park's boundaries . The old-established residents of Cades Cove were angry. Park Commission chief Colonel David Chapman received several threats, including an anonymous phone call warning him that if he ever returned to Cades Cove, he would "spend the next night in hell." Shortly afterwards, Chapman found a sign near the entrance to the cove that read:

COL. CHAPMAN: YOU AND HOAST ARE NOTFY, LET THE COVE PEOPL ALONE. GET OUT. GET GONE. 40 M. LIMIT.

The "40 mile" (64 km) limit referred to the distance between Cades Cove and Chapman's hometown of Knoxville . Despite these threats, Chapman brought a civil suit (condemnation suit) against John W. Oliver in July 1929. The court, however, ruled in Oliver's favor on the grounds that the federal government had never named Cades Cove as an essential part of the national park. Shortly after the verdict, the Secretary of the Interior officially announced that the Cove was a necessary part and another lawsuit was initiated. This time, Oliver lost the case after the case went to the Tennessee Supreme Court. Oliver went to court several times for the value of his 375-acre (1.5 km²) farm, which he valued at $ 30,000 while the court only granted him $ 17,000 with interest. After he was able to get a number of one-year leases, he finally left his property on Christmas Day 1937. The Primitive Baptist Church Congregation met in Cades Cove until the 1960s, despite the Park Service, which wanted to cultivate the land which the church stood.

For about a hundred years prior to the creation of the national park, the valley was extensively used for agriculture and forestry, which resulted in extensive deforestation. Initially the plan was to return the cove to its natural state, but ultimately the National Park Service met the requirement of the Great Smoky Mountain Conservation Association to keep Cades Cove as grazing land. At the direction of cultural management experts like Hans Huth, the agency had the newer buildings demolished and only received the primitive huts and barns that were believed to be representative of the life of the pioneers in the Appalachians.

Historic buildings in Cades Cove

| Cades Cove | ||

|---|---|---|

| National Register of Historic Places | ||

| Historic District | ||

|

Becky Cable House |

||

|

|

||

| location | Townsend , Tennessee | |

| Coordinates | 35 ° 35 '39 " N , 83 ° 50' 31" W | |

| Built | 1818 | |

| NRHP number | 77000111 | |

| The NRHP added | July 13, 1977 | |

Cades Cove was listed as a Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places on July 13, 1977 . The Historic District is delimited by the 2000 ft (610 m) contour line and includes all areas below this altitude, as well as the historical buildings and prehistoric archaeological sites.

The National Park Service currently maintains several buildings in Cades Cove that are believed to be representative of 19th century Appalachian pioneering life. The following list shows the order in which the buildings are to be found along the Cades Cove Loop Road :

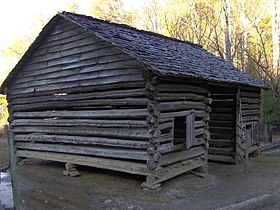

1. The John Oliver Cabin (1822–1823): Dunn reports that the Olivers survived the first winter of 1818–1819 in an abandoned Cherokee cabin and built a simple cabin the following year. Today's hut was a new building of the first hut.

2. The Primitive Baptist Church (1887). The Olivers and Russell Gregory are buried in the adjacent cemetery.

3. The Cades Cove Methodist Church (1902). The oldest Methodist church was established in the 1820s, and the first meeting house around 1840.

4. The Cades Cove Missionary Baptist Church (present building from 1915–1916)

5. The Myers Barn (1920). A more modern hay barn on the way to Elijah Oliver Place .

6. The Elijah Oliver Place (1866). Elijah Oliver (1829–1905) was the son of John and Lucretia Oliver. His first farm was destroyed by the Confederate during the Civil War. The farm has a dog-trot cabin , a chicken coop, a corn store, a well house and a simple stable.

7. The John Cable Grist Mill (1868). John P. Cable (1819-1891), a nephew of Peter Cable, had to build a series of intricate waterways along Mill Creek and Forge Creek to generate enough hydropower for the characteristic overshot waterwheel.

8. The Becky Cable House (1879). The building by the Cable Mill was originally used by Leason Gregg as a store. In 1887 he sold it to John Cables daughter, the single Rebecca Cable (1844-1940). A family tradition has it that Rebecca never forgave her father and refused to marry after her father destroyed her love for children. Several buildings were moved there from other places in the cove. Among other things, a barn, a carriage house, a chicken coop, a molasses kitchen, a sorghum press and a facsimile of a forge.

9. The Henry Whitehead Cabin (1895-1896). This cabin on Forge Creek Road at Chestnut Flats was built by Matilda "Aunt Tildy" Shields and her second husband, Henry Whitehead (1851-1914). Shield's sons from his first marriage were major figures in the moonshine trade.

10. The Dan Lawson Place (circa 1840) was built by Peter Cable in the 1840s and acquired by Dan Lawson (1827-1905) after he married Cable's daughter, Mary Jane . Lawson was the wealthiest resident of the Cove. The farm has the "Peter Cable Cabin" residential building, a smokehouse, a chicken coop and a hay barn.

11. The Tipton Place (1880s) was built by the descendants of William "Fighting Billy" Tipton. The wood paneling was a later addition. In addition to the hut, the farm has a carriage house, a smokehouse, a woodshed and a double-canopy barn (double-cantilever barn).

12. The Carter Shields Cabin (1880s), simple log cabin.

Touring

Although geographically isolated, the cove is now a popular tourist attraction in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. A one-way street leads 11 miles (18 km) once around the cove and is used by thousands of visitors every day. In the main season it can take four hours to complete the route.

The cove is particularly well known for its numerous black bears and numerous deer. Popular hiking trails lead to Abrams Falls (8 km) and Gregory Bald . There is also the opportunity to go horse riding and cycling.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kris Christen: Trapped in the Cove. ( Memento of the original from July 14, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Sightline , Vol. 3 No. 1, Winter / Spring 2002, University of Tennessee Energy, Environment and Resources Center (EERC).

- Jump up ↑ Harry Moore: A Roadside Guide to the Geology of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press 1988: 29.

- ↑ a b Moore 29.

- ^ Moore, 17.

- ^ Moore, 12-13.

- ^ Moore 23-27.

- ↑ Bob Gulden: USA Deepest Caves. June 20, 2013.

- ^ Moore 35.

- ^ Larry Matthews: Caves of Knoxville and the Great Smoky Mountains. Knoxville, Tennessee : National Speleological Society 2008: 157-180.

- ^ Donald K. MacKay, Geology of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (September 14, 1935). Report on file at the Sugarlands Visitor Center Library.

- ↑ From a transcript of a conversation with Wesley Herman Gregory, son of JJ Gregory, made April 22, 1971.

- ↑ Michael Strutin, History Hikes of the Smokies. Gatlinburg: Great Smoky Mountains Association, 2003: 322-323.

- ^ Durwood Dunn: Cades Cove: The Life and Death of An Appalachian Community . University of Tennessee Press , Knoxville 1988, p. 6.

- ↑ Vicki Rozema: Footsteps of the Cherokees: A Guide to the Eastern Homelands of the Cherokee Nation. Winston-Salem, North Carolina : John F. Blair, 1995.

- ↑ James Mooney: Myths of the Cherokee and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee. Nashville: Charles Elder, 1972: 538.

- ↑ a b c Rozema: 183.

- ↑ Dunn: 260.

- ↑ Broken Treaties .

- ↑ Dunn: 13.

- ^ Dunn: 1-9.

- ↑ Dunn: 16-17.

- ↑ Dunn: 20.

- ^ Dunn: 43-44.

- ↑ Dunn: 68.

- ↑ Dunn, 67.

- ↑ Dunn: 82-86.

- ↑ Dunn: 100.

- ^ Dunn: 102-103.

- ↑ Dunn: 112.

- ^ Dunn: 112-113.

- ↑ We believe that Jesus Christ Himself instituted the Church, that it was perfect at the start, suitably adopted in its organization to every age of the world, to every locality of earth, to every state and condition of the world, to every state and condition of mankind, without any changes or alterations to suit the times, customs, situations, or localities. Dunn: 104.

- ↑ Dunn: 119-120.

- ↑ a b Dunn: 125.

- ↑ Dunn: 134.

- ^ Dunn: 135-136.

- ↑ Dunn: 143-144.

- ↑ Michael Frome: Strangers In High Places: The Story of the Great Smoky Mountains. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press 1994: 334.

- ↑ Frome: 334.

- ↑ All these men are public outlaws, and were never recognized as true, loyal mountaineers or as true American citizens, by the rank and file of the mountain people. Daniel Pierce: The Great Smokies: From Natural Habitat to National Park. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press 2000: 21.

- ^ Dunn: 235-236.

- ↑ Dunn, 238-239.

- ^ Dunn: 242-246.

- ^ "Spend the next night in hell." Carlos Campbell: Birth of a National Park In the Great Smoky Mountains. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press 1969: 97-101.

- ↑ Campbell, 98: “Colonel Chapman: You and HOAST note: Leave the people of the Cove alone. Go Go away. 40 miles around. "

- ^ Pierce: 162.

- ↑ Pierce: 166.

- ↑ Campbell: 147.

- ↑ Dunn: xiii – xiv.

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09) ( Memento of the original from June 26, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ^ National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form .

- ↑ Dunn: 81-82.

Web links

- geonames.usgs.gov Cades Cove on the Geonames server.

- Cades Cove , Great Smoky Mountains National Park website

- The Great Smoky Mountains Association - Non-profit partner of the National Park, creator of popular park maps, guides, and books, and operates all official park information and visitor centers

- National Park Service (2010-07-09) . "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- Cades Cove Preservation Association

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park: Plan Your Visit: Cades Cove

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park: Maps