Great Smoky Mountains

| Great Smoky Mountains | |

|---|---|

|

The mountain range as seen from the top of Mount Le Conte . |

|

| Highest peak | Clingmans Dome ( 2025 m ) |

| location | Tennessee and North Carolina , United States |

| part of | Blue Ridge Mountains , Appalachian Mountains |

| Coordinates | 35 ° 34 ′ N , 83 ° 30 ′ W |

| Age of the rock | Alleghenic orogeny |

| surface | 2,114 km² |

| particularities | Great Smoky Mountains National Park |

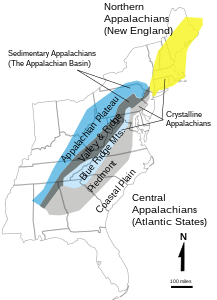

The Great Smoky Mountains (short Smoky Mountains , colloquially the Smokies ) are a mountain range along the border between Tennessee and North Carolina in the southeastern United States . They belong to the Appalachian Mountains and form part of the Blue Ridge Mountains . The mountain range gained particular fame through the Great Smoky Mountains National Park , which has spanned most of the mountain range since it was founded in 1934 and is now the most visited national park in the United States with more than 11 million visitors per year.

The Great Smoky Mountains are part of the Man and the Biosphere Program of UNESCO and are home to around 757 km² of primary forest , making it the largest of its kind east of the Mississippi River . The mixed forests at lower altitudes are among the most biodiverse ecosystems in North America , and the red spruce forest there is the largest of its kind in the world. The Great Smokies also have the greatest density of black bears in the eastern United States and the greatest diversity of salamander species outside of the tropics .

The mountain range is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site . The National Park Service maintains 78 sites within the national park , nine of which are on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). Five areas within the park are registered as Historic Districts in the NRHP .

The Great Smoky Mountains wildfires (forest fires) in 2016 attracted international media interest.

Surname

The designation as smoky ( German "hazy" ) goes back to the natural fog that often covers the mountain range and can also be seen from a distance as a fog flag. The Cherokee Indians gave the landscape the name "Shalonage" = "place of the blue fog". The fog is caused by vegetation, which emits volatile organic compounds that appear as vapor at normal temperatures and atmospheric pressure.

geography

The Great Smoky Mountains stretch from the Little Tennessee River in the southwest to the Pigeon River in the northeast. In the northwest, the mountain range ends in the so-called "Foothills", which include Chilhowee Mountain and English Mountain . In the south, the Smokies are bounded by the Tuckasegee River and in the southeast by Soco Creek and Jonathan Creek . The mountain range lies in the Tennessee counties Blount , Sevier and Cocke as well as in the Counties Swain and Haywood of North Carolina .

Many rivers have their source in the Smoky Mountains, including the Pigeon River, Oconaluftee River, and Little River . They belong to the catchment area of the Tennessee River and are therefore located west of the Eastern North American Divide . The largest river is Abrams Creek , which has its source in Cades Cove and flows into Chilhowee Lake near Chilhowee Dam . The Little Tennessee River feeds five reservoirs ( retention basins , impoundments) along the southwestern borders: Tellico Reservoir , Chilhowee Lake, Calderwood Lake , Cheoah Lake, and Fontana Lake .

Other rivers are Hazel Creek and Eagle Creek in the southwest, Raven Fork at Oconaluftee , Cosby Creek at Cosby and Roaring Fork at Gatlinburg .

Highest elevations

The highest point at 2,025 m is the Clingmans Dome , making it the highest mountain in Tennessee and the third highest in the entire Appalachian Mountains. With a notch height of 1,373 m, it also has the highest in the mountain range.

| mountain | height | Prominence | location | Named after |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clingman's Dome | 2,025 m | 1,373 m | center | Thomas Lanier Clingman (1812-1897), surveyor |

| Mount Guyot | 2,018 m | 482 m | Eastern mountains | Arnold Henri Guyot (1807-1884), surveyor |

| Mount Le Conte | 2,010 m | 415 m | center | Joseph LeConte or John LeConte , scientist |

| Mount Chapman | 1,960 m | 176 m | Eastern mountains | David C. Chapman (1876–1944), proponent of the national park |

| Old Black | 1,939 m | 52 m | Eastern mountains | Fir forest at the summit |

| Air Tea Knob | 1,894 m | 96 m | Eastern mountains | Oconaluftee River |

| Mount Kephart | 1,895 m | 200 m | center | Horace Kephart (1862-1931), writer |

| Mount Collins | 1,888 m | 142 m | center | Robert Collins, mountain guide |

| Marks Knob | 1,878 m | approx. 76 m | Eastern mountains | |

| Tricorner Knob | 1,873 m | 48 m | Eastern mountains | Cross between the Balsam crest and the Great Smokies crest |

| Mount Hardison | 1,873 m | 41 m | Eastern mountains | James Archibald Hardison (1867–1930), member of the North Carolina Park Commission |

| Andrews soon | 1,801 m | 48 m | center | Probably Andrew Thompson, former settler |

| Mount Sterling | 1,781 m | 202 m | Eastern mountains | Probably were lead deposits mistaken for the mountain of silver held |

| Silers soon | 1,706 m | 102 m | Western mountains | Jesse Siler, of the mountain as pasture used |

| Thunderhead Mountain | 1,684 m | 332 m | Western mountains | The mountain is permanently covered with clouds |

| Gregory Soon | 1,508 m | 337 m | Western mountains | Russell Gregory (1805–1863), resident of Cades Cove |

| Mount Cammerer | 1,502 m | 2 m | Eastern mountains | Arno B. Cammerer (1883–1941), former director of the National Park Service |

| Chimney tops | 1,440 m | approx. 61 m | center | Optical similarity to chimneys |

| Blanket Mountain | 1,404 m | approx. 152 m | Western mountains | Ceiling left behind by surveyor Return Meigs at the summit as a reference point |

| Shuckstack | 1,225 m | 91 m | Western mountains |

climate

Due to their sometimes more than 2 km height, the Great Smoky Mountains have comparatively high amounts of precipitation , between 130 and 200 cm per year and can lead to flooding. The snowfall in winter can be correspondingly intense - especially at higher altitudes. In the vicinity of the mountain range, the annual rainfall is between 100 and 130 cm.

The area is also repeatedly crossed by low pressure areas from former hurricanes . For example, the remnants of Hurricane Frances in 2004 caused severe flooding, landslides and high winds caused damage to the ground , which was exacerbated by the subsequent Hurricane Ivan . The former Hurricane Hugo also caused great damage in the Smokies in 1989.

geology

The Great Smoky Mountains consist largely of layers of rock from the late Precambrian in the form of weakly metamorphic sandstone , phyllite and slate . The oldest layers date from the Early Precambrian and are located in the Raven Fork Valley and along the upper Tuckasegee River between Cherokee and Bryson City . They mainly contain metamorphic gneiss , granite and slate. At the foothills of the Smokies and in some valleys such as Cades Cove there are also sedimentary rocks from the Cambrian .

Over a billion years ago, the oldest layers of the Smokies were formed by volcanic rock deposits and by marine sediments in a primordial ocean . In the late Precambrian, that ocean expanded, and eroding land masses piled up on the ocean shelf to form the Ocoee Supergroup , which includes the Great Smoky Mountains.

At the end of the Paleozoic, there was a thick layer of marine sediments on the bottom of the primordial ocean, from which limestone was formed. During the Ordovician collided the North American and African tectonic plates together destroyed whereby the ocean and the Alleghanian orogeny was initiated during the Appalachians were formed. During the Mesozoic , the soft outer layers of the newly formed mountains eroded, exposing the older layers of the Ocoee Supergroup .

About 20,000 years ago, glaciers stretched from the Arctic to North America . Although they did not reach the area of the Great Smoky Mountains, they did lead to climatic changes in the mountain range, with mean temperatures falling and rainfall increasing. In the higher elevations, trees could not survive and were replaced by vegetation that is more typical of tundra . Boreal coniferous forests extended in the valleys and on the slopes below 1,500 m. The permanent alternation of frost and thaw created seas of rocks , as they are often to be found at the foot of large mountains.

Between 16,500 and 12,500 years before our era, the glaciers retreated and enabled the mean average temperatures to rise again. The tundra plants disappeared, while the coniferous forests were only preserved in the highest areas and were replaced by hardwood in the other areas . Around 6,000 years ago, the temperatures that had been rising until then began to cool down again.

flora

Large-scale clearings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries destroyed most of the Smokies' forests. In 2008, the National Park Service assumed that an estimated 757 km² of primary forest still exist in the region , making the Great Smoky Mountains the largest primary forest in the eastern United States today. Of the approximately 1,600 angiosperms TYPES in the Smokies more than 100 bush and tree species are as indigenous to watch. More than 2,000 species of fungi and 450 species of non-vascular plants also thrive in the region .

The forests of the Smokies are usually divided into three zones

- Mixed forests in valleys,

- Mixed forests on slopes and

- boreal coniferous forests at the highest points

divided.

At medium altitudes there are some places with little or no tree population, so-called "Appalachian balds", which cannot be traced back to human logging. The soil in these areas is very dense either with grass or a mixture of rhododendrons and mountain laurel. Mixed oak and pine forests are found especially on the south-facing slopes of the North Carolina area . There are also some stocks of Canadian hemlocks along rivers and on slopes over 1,000 m .

Mixed forests in valleys

The mixed forests (Cove Hardwood Forests) of the southern Appalachians are among the most biodiverse in North America. In the area of the Great Smoky Mountains, it is mainly secondary forest , although around 290 km² still consists of primary forest . Some of the oldest and tallest trees in the mountain range are in the Albright Grove on the Maddron Bald Trail between Gatlinburg and Cosby.

There are more than 130 different types of trees in the Smokies. The most common are yellow birch , American linden , yellow horse chestnut , tulip trees , storax trees ( Halesia carolina ), sugar maples , cucumber magnolias , hickory ( Carya ovata ), Carolina hemlocks and Canadian hemlocks . The previously also common occurring American Chestnut was amended by entrained in the 1920s chestnut blight completely destroyed.

In the undergrowth to find dozens of species of shrubs and climbing plants in particular, Canadian Judas trees ( Cercis canadensis ), Cornus florida , Catawba- rhododendrons ( Rhododendron catawbiense ), Mountain Laurel and forest hydrangeas .

Mixed forests on slopes

The mean annual temperatures in the higher elevations of the Smokies are low enough to allow forests that otherwise occur more in the northern USA, the so-called “Northern Hardwood Forests”. The highest deciduous forest in the eastern United States is found on the slopes of the Great Smoky Mountains. Around 113 km² of this is primary forest.

Trees such as yellow birch and American beech dominate the hillside , but there are also stands of American linden ( tilia heterophylla ), Vermont maple , striped maple and yellow horse chestnut. In the undergrowth, various composite flowers , goldenrod , Canadian tormenti , hydrangeas and various types of grass and ferns thrive .

In the high gorges of the mountain range there are also areas in which beeches are almost exclusively found . These are often twisted and twisted due to the strong winds that prevail there. It is not known why other tree species like the American red spruce did not get as far as this.

Boreal coniferous forest

The spruce -fir forests of the Great Smoky Mountains form a boreal coniferous forest as a relic of the last Ice Age, which was too cold for the development of deciduous and mixed forests . Due to the temperature increases 12,500 and 6,000 years ago, the coniferous forests in the lower and middle altitudes of the mountain range were displaced by deciduous and mixed forests, so that pure coniferous forests now only occur in locations above 1,600 m. About 43 km² of the boreal coniferous forest are primary forest.

The coniferous forests of the Smokies essentially consist of American red spruce and Fraser fir , although larger populations of the Fraser fir have been destroyed by the pine stem louse since the 1960s . On the northwest slopes of the Old Black and on the summit of the Clingmans Dome there are still dead remains of the Fraser firs. The American red spruce is therefore the most abundant tree today in the heights of the Smokies, although a large part of the red spruce was felled during the First World War . The oldest trees standing here are estimated to be 300 years old, and the largest reach a height of more than 30 m.

Rhododendrons, American mountain ash trees ( Sorbus americana ), fire cherries ( Prunus pensylvanica ), blackberries and snowballs ( Viburnum lantanoides ) are widespread in the undergrowth of the coniferous forests . Shady spots are dominated by worm ferns ( Dryopteris campyloptera ) and the forest lady fern . In addition, over 280 species of moss thrive in these regions.

Wildflowers

The multitude of wildflowers that grow in the mountains include Monarda , Weisswurzen , heart flowers , forest lilies and orchids . With the Catawba rhododendron and the Rosebay rhododendron , the Smokies have two indigenous rhododendron species. Due to the diversity of plants, there are always areas in the mountains from spring to autumn that are covered with differently colored flowers.

fauna

The Great Smoky Mountains are home to 66 species of mammals, over 240 species of birds, 43 amphibians, 60 fish and 40 reptile species. The mountains have the largest population density of American black bears east of the Mississippi, which is why this animal is a symbol for all wild animals of the Smokies and is regularly depicted on brochures of the national park. Most of the adult Smokies black bears weigh between 45 kg and 136 kg, some even weigh 225 kg.

White-tailed deer are also common among the mammals , the number of which has increased significantly with the establishment of the national park. The bobcat is the only type of cat represented, although there are occasional sightings of pumas . In the recent past, coyotes have also immigrated to the Smokies and are now considered to be indigenous there. There are also larger populations of red and gray foxes .

European wild boars were introduced to the region in the early 20th century and have become widespread in the southern Appalachian Mountains, but are considered a nuisance due to the typical churning of the soil as they forage. They are also said to make the bears struggle for food, so the park administration pays premiums for shooting wild boars and leaving them in places that are frequented by the bears.

More than two dozen species of rodents live in the Great Smoky Mountains , including the endangered Northern Flying Squirrel . Ten species of bats were also counted, including the endangered Indiana mouse- eared bat . The management of the national park has succeeded in resettling the North American otter and elk in the mountain range. A corresponding attempt with red wolves failed in the 1990s; the animals were captured and relocated to the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in North Carolina.

The different forests of the Smokies provide a habitat for a variety of bird species. Among the most common representatives at lower altitudes are Rotaugenvireos , wood thrushes , Turkeys , titmice Warbler , Ruby-throated hummingbirds and Indians tits . In higher regions are ravens , wrens ( Troglodytes hiemalis ), Schwarzkopf tits , Yellow-bellied Sapsucker , Winter buntings , spruce Warbler , Yellow-crowned warbler and Canada Warbler most frequently encountered. In the drier areas of the mixed forests there are also pottery birds , night swallows ( Antrostomus vociferus ) and downy woodpeckers . Also common are bald eagles , golden eagles , peregrine falcons , Rotschwanzbussarde and Streifenkauze , eastern screech owl and Sägekauze in the Smokies before.

With the forest rattlesnake and the North American copperhead, there are also two poisonous species of snake in the mountains. Other common species of reptiles in the Smokies are Eastern Box turtles , spiny lizards ( Sceloporus undulatus ), Erdnattern and water snakes ( nerodia sipedon ).

The mountains are home to 31 species from five of the nine known salamander - families one of the world's most diverse salamander populations. The red-cheeked forest salamander in particular occurs exclusively in the Smokies, while the imitator salamander ( Desmognathus imitator ) occurs in the Smokies as well as in the nearby Plott Balsams and Great Balsam Mountains . The mud devil lives in the fast flowing rivers of the mountain range . The other amphibian species of the Smokies include real toads ( Bufo americanus ), North American bullfrogs , forest frogs , tree frogs ( Pseudacris feriarum ), real frogs ( Rana clamitans melanota ) and spring peepers .

Trout , lamprey , real perch , carp fish , perch-like and sucker carp are common in the rivers of the Great Smoky Mountains . The brook trout is the only native species of trout in the Smokies, although rainbow trout and trout were introduced as early as the early 20th century. Since the brook trout is inferior to the latter larger fish when it comes to foraging, it is only found today at altitudes above 900 m. The smokies also contain the protected catfish ( Noturus flavipinnis or Noturus baileyi ), whitefish ( Cyprinella monacha ) and jumping bass ( Etheostoma percnurum ).

Threats to the ecosystem

In the higher regions of the mountain range, air pollution increasingly leads to the death of red spruce, in lower areas to the decline of oaks. Invasive species such as the East Asian aphid adelges tsugae attack the hemlock fir, while the fir trunk louse prefers to attack the fraser fir. The ladybird pseudoscymnus tsugae was introduced specifically to control aphids.

Smog regularly drifts into the mountains from both the southeastern states and the Midwest of the USA and leads to a considerable reduction in visibility. The United States Environmental Protection Agency issues daily smog forecasts for the nearby cities of Knoxville, Tennessee and Asheville, North Carolina .

In response to the threats to the environment, relevant organizations have taken on the topic, above all the Friends of the Smokies, founded in 1993 . They support the National Park Service in its tasks by informing the public, collecting donations and providing volunteers for projects.

history

prehistory

It is likely that the Indians used the Great Smoky Mountains as a hunting ground as early as 14,000 years ago. A large number of artefacts from the Archaic period (approx. 8,000 - 1,000 BC) were found in the national park, including parts of hunting weapons from that time. Excavations have also revealed ceramics from the woodland period that are more than 2000 years old .

During the Mississippi period (approx. 900-1600 AD), the Indians increasingly practiced agriculture and therefore moved from the forests to the fertile valleys on the outer edge of the Smokies. Settlements from this era were found on the Little Tennessee River in the 1960s and named in the Cherokee Citico and Toqua language . Fortified settlements of this period have been excavated near Sevierville and Townsend, Tennessee .

Most of these settlements belonged to the Chiefdom Chiaha , which was on an island that is now below the waterline of Douglas Lake . The expeditions of Hernando de Soto (1540) and Juan Pardo (1567) also took the participants to Chiaha, where they spent a long time. Pardo also visited Chilhowee and Citico.

The Cherokee

When the first European settlers reached the southern Appalachians in the 17th century, these were largely settled by the Cherokee , with the Great Smoky Mountains at the center of their territory. Numerous myths and legends of the Indians entwine around the mountains; so involved will have a well-hidden magic lake, and a medicine man of Shawnee called Aganunitsi is thought to be in the foothills of the mountains horned snake Uktena were looking for. The Cherokee called Gregory Bald "Tsitsuyi" (Rabbit Square) and believed that the mountain was the home of the Big Rabbit (Nanaboso). Other Cherokee place names in the Smokies were duniskwalgunyi (forked antlers) for the chimney tops and kuwahi (mulberry place) for Clingman's Dome .

Most of the Cherokee settlements were in the river valleys on the farthest edge of the Smokies. Together with the Unicoi Mountains, these formed a dividing line between the so-called Overhill Cherokee in what is now Tennessee and the Cherokee in what is now North Carolina. The overhill settlements of Chilhowee and Tallassee are now at the bottom of Chilhowee Lake .

Probably the oldest Cherokee village called Kituwa was on the Tuckasegee River near Bryson City. The village of Oconaluftee was located near today's visitor center and was the only year-round inhabited Cherokee settlement within the national park.

European settlement

The first European settlers and explorers reached western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee in the middle of the 18th century. The increased influx of settlers after the end of the Seven Years' War led to conflicts with the Cherokee, who legally owned most of the lands. When the Indians sided with the British with the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1776 , the Americans began an invasion of Cherokee Territory. General Griffith Rutherford set fire to nearly all of North Carolina's Indian settlements, including Kituwa, while John Sevier did the same in Tennessee with the Overhill settlements. In 1805, the remaining Cherokee ceded control of the Great Smoky Mountains to the United States government. Although most of the tribesmen were forced westward on the Path of Tears in 1838 , some - aided by William Holland Thomas - stayed behind and now form the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians .

In the 1780s there were several border posts along the Smokies foothills, including Whitson's Fort (now Cosby, Tennessee ) and Wear's Fort (now Pigeon Forge ). The first settlers moved to the area in the 1790s, and in 1801 the brothers William and John Whaley became the first to settle in the Greenbrier Valley, now part of the national park. In 1802 , William Ogle, originally from Edgefield, South Carolina , reached the White Oak Flats and began working as a lumberjack. After his death, his wife Martha Jane Huskey and other families became the founders of what is now Gatlinburg.

The Cades Cove valley was mostly inhabited by families who had purchased land from speculator William "Fighting Billy" Tipton. John and Lucretia Oliver were the first of these settlers to reach the valley in 1818. In 1836, after a stint in Cades Cove, Moses and Patience Proctor became the first settlers to settle on the North Carolina side of Hazel Creek . The Cataloochee Valley was first settled by the Caldwell family in 1834.

The main economic basis of the southern Appalachians in the early 19th century consisted of subsistence farming . The average farm had around 20 acres of land, some of which were used as pasture and arable land, and others were forest. The typical log houses of the first settlers measured 6 mx 5 m, but were gradually enlarged and later replaced by wooden houses built from boards. Most farms had at least one barn for storing tools and seeds, a “spring house” built over a spring for cooling food, a smokehouse for preserving meat, a chicken coop and a granary . Some farmers also ran flour mills , general stores , and sorghum presses.

Religion played an important role in the everyday life of the settlers, so that social life was concentrated around church buildings. In the Great Smoky Mountains region, the religions Baptism , Methodism and Presbyterianism were predominant.

Civil War

Both North Carolina and Tennessee joined the Confederate States of America in 1861 at the start of the Civil War . In the vicinity of the Great Smoky Mountains, support from the northern states was greater than in other regions of the two states. On the Tennessee side of the mountains, cities supported the Northern States, while on the North Carolina side, support for the Confederation predominated. In Tennessee, 74 percent of Cocke Counties , 80 percent of Blount Counties, and 96 percent of Sevier Counties voted against the split. In the North Carolina counties of Cherokee , Haywood , Jackson and Macon , around 46% of the population voted for secession.

There were no major battles in the Smokies during the war, but there were occasional minor skirmishes. The Cherokee chief William Holland Thomas founded a unit consisting almost exclusively of Cherokee soldiers, crossed the mountains with him in 1862 and occupied the city of Gatlinburg for several months in order to protect the potassium nitrate mines on Mount Le Conte. The northerners of Cades Cove quarreled with the Hazel Creek residents who supported the Confederation, and both parties regularly crossed the Smokies to steal cattle from each other. The residents of Cosby and Cataloochee behaved similarly. Two incidents in particular that occurred during the Civil War in the Great Smoky Mountains became known: First, Russell Gregory, after whom Gregory Bald is named, was murdered by Bushwhackers in 1864 shortly after he had led a group of Confederate soldiers to Cades Cove. Second, George Kirk led a raid on Cataloochee in which he killed or wounded 15 Union soldiers who were recovering in a makeshift hospital.

Logging

The inaccessibility of the forests of the Great Smoky Mountains initially prevented major clearing, so that there were only isolated logs until the 19th century. It was only when wood resources in the northeastern United States and the Mississippi Delta began to decline and demand for wood skyrocketed after the end of the Civil War that ways were sought to reach the pristine forests of the southern Appalachians. In the 1880s, the first companies began clearing the Smokies on a large scale and used Klausen or wooden barriers on rivers (see photo) to transport the tree trunks to the sawmills downstream. The largest ventures included the English Lumber Company on the Little River, Taylor and Crate on Hazel Creek, and the Alexander Arthur impacts on the Pigeon River. However, all three companies had to give up after just a few years after flooding destroyed their dams and barriers.

Towards the end of the 19th century, technical advances in forest railways and band saws made large-scale logging possible in the mountainous regions of the southern Appalachians. The largest enterprise of this kind was the Little River Lumber Company , which was active in the Little River catchment area from 1901 to 1939 and founded what is now Townsend, Elkmont and Tremont for its employees .

The second largest logging company was the Knight Lumber Company on Hazel Creek, which existed from 1907 to 1928 and the ruins of which are still visible today. The companies Three M Lumber and Champion Fiber also gained importance in the catchment area of the Ocanaluftee River. By the time all the logging companies went out of business in the 1930s, they had already cleared two-thirds of the forest in the Great Smoky Mountains.

National park

Wilson B. Townsend, owner of the Little River Lumber Company , began promoting Elkmont as a tourist destination in 1909. A few years later, the Wonderland Hotel and Appalachian Club were available to accommodate visitors from Knoxville . In the early 1920s, some Appalachian Club members , including David C. Chapman , began to seriously consider establishing a national park in the Great Smoky Mountains. Chapman was subsequently responsible as chairman of the Great Smoky Mountains Park Commission , collecting donations for the property purchase and taking over the coordination between regional, state and federal agencies.

The founding of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was much more complex than its predecessors, Yellowstone National Park and Yosemite National Park , which were already owned by the federal government. Not only did lumberjack companies have to be convinced to sell lucrative exploitation rights, but thousands of smaller farms had to be bought up and, in some cases, entire communities had to be relocated. In addition, there were regulations in the laws of North Carolina and Tennessee at the time that explicitly prohibited the use of taxpayers' money for national park purposes. Despite these difficulties, the Park Commission was able to successfully complete most of the land purchases by 1932, so that the national park could be officially opened in 1934. The then US President Franklin D. Roosevelt personally chaired the opening ceremony at Newfound Gap .

Culture and tourism

The local economy is largely based on tourism , with a particular focus on the cities of Pigeon Forge , Gatlinburg and Cherokee . In 2006, the Great Smoky Mountains Heritage Center was founded in Townsend, Tennessee to preserve the local culture.

In summer rafting is particularly popular in the mountains , in winter the higher elevations offer good conditions for downhill runs .

The Country singer Dolly Parton grew up on a small farm in the Smokies and wrote many songs about the area. She also starred in the 1986 film A Smoky Mountain Christmas .

literature

- Margaret Lynn Brown: The Wild East: A Biography of the Great Smoky Mountains. University Press of Florida, Gainesville 2000, ISBN 978-0-8130-1750-1 .

- Hattie Caldwell Davis: Cataloochee Valley: vanished settlements of the Great Smoky Mountains . WorldCom, distributed by Alexander Distributing, Alexander, NC 1997, ISBN 978-1-56664-108-1 .

- C. Kenneth Dodd: The amphibians of Great Smoky Mountains National Park . University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, Tenn. 2004, ISBN 978-1-57233-275-1 .

- Durwood Dunn: Cades Cove: the life and death of a southern Appalachian community, 1818-1937 . University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville 1988, ISBN 978-1-57233-764-0 .

- Rose Houk: Great Smoky Mountains National Park . Houghton Mifflin, Boston 1993, ISBN 978-0-395-59920-4 .

- Donald W. Linzey: Mammals of Great Smoky Mountains National Park . McDonald & Woodward Pub. Co., Blacksburg, Va. 1995, ISBN 978-0-939923-48-9 .

- Harry L. Moore: A Roadside Guide to the Geology of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park . 1st edition. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, Tenn. 1988, ISBN 978-0-87049-558-8 .

- Duane Oliver: Hazel Creek from then till now . Stinnett Printing, Maryville, Tennessee 1989, OCLC 866667599 , p. 2-3 .

- Arthur Stupka: Notes on the birds of Great Smoky Mountains National Park . University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, Tenn. 1963, OCLC 167612 .

- Vic Weals: Last train to Elkmont: a look back at life on Little River in the Great Smoky Mountains . Olden Press, Knoxville, TN 1993, ISBN 978-0-9629156-1-1 .

Web links

- Official website

- Biodiversity in the national park

- Great Smoky Mountains Association website

- Site of the Great Smoky Mountains Institute in Tremont

Individual evidence

- ↑ Park Statistics. National Park Service , January 12, 2017, accessed September 22, 2017 .

- ↑ cf. Houk, p. 198.

- ^ A b c d e Mary Byrd Davis: Old Growth in the East: A Survey. North Carolina. (PDF) January 23, 2008, archived from the original on February 17, 2012 ; accessed on September 26, 2017 (English).

- ↑ cf. Houk, p. 50.

- ↑ cf. Houk, pp. 112-119.

- ↑ Laura Naranjo: Volatile trees. NASA , November 20, 2011, accessed September 26, 2017 .

- ↑ cf. Moore, p. 32.

- ↑ a b cf. Houk, pp. 10-17.

- ↑ a b cf. Moore, pp. 40-44.

- ↑ Nature - Great Smoky Mountains. National Park Service , accessed September 26, 2017 .

- ↑ cf. Houk, p. 41.

- ↑ cf. Houk, pp. 21-23.

- ↑ cf. Dodd, pp. 46-47.

- ↑ Marti Davis: Serene virgin forest gives respite from July heat. KnoxNews, July 9, 2006, archived from the original on March 3, 2007 ; accessed on September 26, 2017 (English).

- ↑ cf. Houk, pp. 24-25.

- ↑ cf. Houk, pp. 25-26.

- ↑ cf. Houk, p. 28.

- ↑ cf. Houk, pp. 28-29.

- ↑ cf. Houk, p. 30.

- ↑ cf. Houk, pp. 50-53.

- ↑ cf. Houk, pp. 50, 54-55.

- ↑ cf. Linzey, p. 1.

- ↑ cf. Linzey, pp. 88-89

- ↑ cf. Linzey, pp. 65-66

- ↑ cf. Linzey, pp. 93-94

- ^ National Public Radio: Wild Hogs In The Smokies. April 7, 1998, accessed September 29, 2017 (English, radio broadcast).

- ↑ a b Mammals - Great Smoky Mountains National Park. National Park Service , November 9, 2015, accessed September 29, 2017 .

- ↑ cf. Linzey, pp. 1, 21 and 40.

- ↑ cf. Stupka, p. 12.

- ↑ cf. Stupka, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ cf. Stupka, pp. 37-40.

- ↑ cf. Stupka, p. 42.

- ↑ cf. Stupka, pp. 1, 67-72.

- ↑ cf. Houk, p. 131.

- ↑ cf. Dodd, pp. 7-13.

- ↑ cf. Dodd, pp. 185-186.

- ↑ cf. Dodd, p. 123.

- ↑ cf. Dodd, p. 26.

- ↑ cf. Dodd, pp. 86-87, 230-231, 243.

- ^ Fish - Great Smoky Mountains National Park. National Park Service , August 19, 2015, accessed September 29, 2017 .

- ↑ Marc S. McClure, Carole AS-J. Cheah: Pseudoscymnus tsugae (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). In: Biological Control: A Guide to Natural Enemies in North America. Cornell University , archived from the original on May 31, 2008 ; accessed on September 30, 2017 (English).

- ^ Friends of the Smokies. 2017, accessed on September 30, 2017 .

- ^ Lisa Byerley Gary: Back to the Future. In: Sightline, vol. 2, no. 1. 2001, archived from the original on January 7, 2015 ; accessed on September 30, 2017 (English).

- ^ Cades Cove Opportunities Plan. National Park Service , accessed September 30, 2017 .

- ↑ Richard R. Polhemus, Arthur E. Bogan, Jefferson Chapman: The Toqua site 40MR6: a late Mississippian, Dallas phase town . Ed .: National Park Service (= Report of investigations . Volume 1 , no. 41 ). University of Tennessee, Department of Anthropology, Knoxville, Tenn. 1987, OCLC 17575211 , pp. 1240-1246 (English).

- ^ Charles M. Hudson, Paul E. Hoffman: The Juan Pardo Expeditions: Explorations of the Carolinas and Tennessee, 1566-1568 . University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa 2005, OCLC 938924784 , p. 36-40, 105 (English).

- ↑ James Mooney: Myths of the Cherokee and Sacred formulas of the Cherokees . Kessinger, Whitefish, Montana 2007, ISBN 978-0-548-13704-8 (English, 576 pages, first edition: Charles and Randy Elder-Booksellers, Nashville, Tenn. 1982).

- ^ Mooney, 407.

- ^ Mooney, 516.

- ↑ Gerald F. Schroedl: Overhill Cherokees. In: The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society, December 25, 2009; accessed October 5, 2017 .

- ↑ cf. Oliver, pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Vicky Rozema: Footsteps of the Cherokees: a guide to the Eastern homelands of the Cherokee Nation . John F. Blair, Winston-Salem, NC 1995, ISBN 978-0-89587-133-6 , pp. 58-60 .

- ↑ Ken L. Jenkins, Carson Brewer: Great Smoky Mountains National Park . Graphic Arts Center Pub., Portland, Oregon 1993, ISBN 978-1-55868-126-2 , pp. 18 .

- ↑ cf. Dunn, pp. 1-9.

- ↑ cf. Oliver, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ cf. Davis, pp. 17-32.

- ↑ Jerry L. Wear: Sugarlands: a lost community of Sevier County . Ed .: Sevierville Heritage Committee. Sevierville, Tenn. 1986, OCLC 25165161 , p. 5-6 (English, 94 pages).

- ↑ Eric Russell Lacy: Vanquished volunteers: East Tennessee sectionalism from statehood to secession . East Tennessee State University Press, Johnson City 1965, OCLC 1631090 , p. 217-233 .

- ^ Civil War Journal: Divided Loyalties. National Park Service , September 6, 2017, accessed October 8, 2017 .

- ↑ cf. Oliver, pp. 44-45.

- ↑ cf. Dunn, pp. 135-136.

- ↑ cf. Davis, p. 72.

- ↑ Wilma Dykeman, Douglas W. Gorsline: The French Broad . Ed .: Fitzgerald Rivers of America Collection, Library of Congress. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York 1974, ISBN 978-0-03-011491-5 .

- ↑ cf. Weals, pp. 1-3.

- ↑ cf. Oliver, pp. 55-56.

- ↑ cf. Weals, pp. 24-28.

- ↑ cf. Olver, pp. 58-64.

- ↑ Michal Strutin, Steve Kemp, Kent Cave: History hikes of the Smokies . Great Smoky Mountains Association, Gatlinburg, TN 2003, ISBN 978-0-937207-40-6 , pp. 125, 325 .

- ↑ cf. Weals, p. 27.

- ^ Daniel S. Pierce: The Great Smokies - from natural habitat to national park . 1st edition. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville 2000, ISBN 978-1-57233-076-4 , pp. 111-120 .