Square notation

In the history of musical notation, square notation is understood to be the last stage of development of the pitch-indicating (diastematic) neumes before the introduction of the modal notation , which is also used to indicate the pitch length and is mainly used for Gregorian chant . The rhythmic differentiation is always indicated in the original square notation. Since the beginning of restitution around the middle of the 19th century, symbols for stretching and tone lengthening have been added to the square notation, which better differentiate the rhythm.

development

Square notes get their name from the predominantly square shape of the notes made by the use of quills . It made squares and diamonds easier to write than circles or other shapes. Alternatively, the horseshoe nail notation with diamonds as noteheads was created using inclined springs . The square notation has its origin in the invention of the horizontal neumen lines and the clefs by Guido of Arezzo in the first half of the 11th century. With this notation system it was possible to describe the pitch of individual tones and thus also to define the tone intervals . The original square notation, however, hardly contains any information on the length of the notes, so that the interpretation of the chants was often mensuralistic or at times even equalistic . However, these forms of interpretation are now considered to be out of date; the rich rhythmic structure in the adiastematic neum systems, as can be found in various manuscripts that were largely unpublished at the time, oppose this.

The Roman chorale neumes that are widespread in church music today were standardized in the 19th century based on the example of the square neumes that have been in use since the end of the 12th century , such as those found in the Jena song manuscript shown . The old notation is deliberately used in modern liturgical choir books. In more recent publications, the square neumes are sometimes also reproduced in the notation of the further developed neography , which allows a better differentiation of the rhythms to be recognized.

In a slightly modernized modification, the square neumes are still used today in the Catholic liturgy in the corresponding choral books of Gregorian chant , such as the Liber Usualis or the Graduale Romanum . Newer chorale books such as Graduel Neumé (1966), Graduale Triplex (1979) or Graduale Novum (2011) show adiastematic neumes in addition to the square notation, which are added directly above or below the square neumes. The singers can then use the square neumes to identify the clear relative pitches and use the adiastematic neumes to determine the exact rhythm.

description

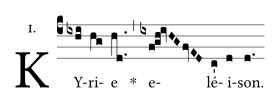

The melody is sung from left to right, with the pes , in which both squares are on top of each other, the lower note is sung first. The text is with the first vowel of the respective syllable under the first neume belonging to this syllable.

The melodies are usually notated in one of the eight church keys and diatonic , which is indicated by a corresponding Roman or Arabic numeral.

The first letter of the lyrics is often used as an initial .

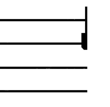

Neum lines

In the square notation, four horizontal neumen lines are usually used for the notation of the melodies, which define four pitches in intervals of thirds. One of the neumen lines is assigned the pitch C or F by a clef . However, this pitch is not absolute, but merely describes a tone that is above one of the two semitones of the tone scale . The clef can be on any of the four lines, depending on the pitch of the piece. It is also possible that the key is on a different line for a new line. In some manuscripts both clefs are set at the same time. Auxiliary lines are used for pitches that are at least a third higher than the top neum line or at least a third lower than the bottom neumen line .

- Clef in square notation

Asteriscus

An asteriscus (asterisk *) in the text indicates at which point the choral schola joins the verse started by one or more cantors .

Single tonumen

The simplest single tonume is the punctum. A neume with a vertical stem to the right of the square neume is called a virga . The quilisma occupies a special position among the individual tonumen , which is represented in a jagged manner and is usually sung as a light passing note or with a light vibrato and usually appears in connection with a pes . In certain triple tonumens (for example in the Climacus), the square punctum is inclined by 45 ° to the side, so that the diamond-shaped punctum inclinatum is created.

- Single tonumen

Multi-tonne

Liquescences are often used for syllable sequences in which the first ends with a consonant and the second begins with a consonant, in which the last tone of the first syllable is represented as small cue notes in the square notation . This presentation is intended to advise the singers to articulate the consonants separately, which is usually not a problem for German native speakers, since such consonant sequences are common in the German language.

Several Einzeltonneumen can different Doppeltonneumen and Dreifachtonneumen or more such Gruppenneumen to Mehrgruppenneumen be assembled. The torculus resupinus flexus (see illustration on the right) is composed, for example, of the triple- barreled torculus and the double- barreled clivis (synonym for flexa ).

Alteration

The tone at the pitch H can be altered down by a semitone using the B minor notation . Such an alteration may apply to the entire melisma on the corresponding vowel. The notation of B durum cancels this alteration.

- Lower and upper alternation in square notation

Custos

At the end of a neum line, a custos (Latin for guardian) is often set, which indicates the pitch of the first tone of the next line. The custos is an auxiliary sign and consists of a halved neume that is not sung, but is intended to help the singer find the connection to the first neume of the next line.

Stretch marks

Stretches or tone extensions can be illustrated by morae behind a single tonum and episemes above or below a neume or group neume . A mora is indicated by a dot behind the neume, an episeme is indicated by a line above or below the neume. The ictus is indicated by a vertical line, but is usually no longer considered as a stress sign today.

- Examples of morae in the square notation for single tonumen

- Examples of episemes in square notation

The additional symbols such as the point, the vertical and horizontal episem, the connecting symbol between notes and the comma on the top line (not shown here) were entered by the monks of Solesmes in their (very widespread) chorale editions. In original manuscripts using square notation, these interpretation signs are not present.

Pause

Breathing caesuras or pauses to structure the text are indicated by the pause . They have been added to chants that are originally in adiastematic notation to give the singers a better orientation. The pause symbols do not have a fixed length and are not anchored in a meter . The pausa finalis usually comes at the end of a verse.

- Rest marks in square notation

In the chorale books (in square notation) from Solesmes , these signs are also indicated as signs of the structure (Latin signa interpunctionis ), or divisio minima, minor, maior et finalis .

Digital typesetting

Square notation is not the primary focus of modern music notation programs . Some still contain functions for setting square notation or are even specially written for them.

- Lilypond also allows the typesetting of square notation and other older notation systems. However, this feature will not be further developed.

- capella contains a character set for square notation including common ligatures.

- Gregorio is a program that was specially made for this purpose. In connection with LaTeX it offers high quality music notation. Numerous abbeys use it for publications.

- Grégoire is a proprietary WYSIWYG program for square notation.

literature

- Luigi Agustoni : Gregorian chant. In: Hans Musch (ed.): Music in worship. A manual for basic training in Catholic church music. Volume 1: Historical basics, liturgy, liturgical chant. 5th unchanged edition. ConBrio Verlags-Gesellschaft, Regensburg 1994, ISBN 3-930079-21-6 , pp. 199–356.

- Luigi Agustoni, Johannes Berchmans Göschl : Introduction to the interpretation of the Gregorian chant (= Bosse-Musik-Paperback 31). 3 volumes (volume 2 in two sub-volumes). Bosses, Regensburg,

- Volume 1: Basics. 1987, ISBN 3-7649-2343-1 .

- Volume 2, Part 1: Aesthetics. 1991, ISBN 3-7649-2430-6 .

- Volume 2, Part 2: Aesthetics. 1991, ISBN 3-7649-2431-4 .

- Eugene Cardine : Gregorian Semiology. La Froidfontaine, Solesmes 2003, ISBN 2-85274-049-4 .

- Bernhard K. Gröbler: Introduction to Gregorian Chant. 2nd revised and expanded edition. IKS Garamond, Jena 2005, ISBN 3-938203-09-9 .

- Stefan Klöckner : Manual Gregorian Chant. Introduction to the history, theory and practice of Gregorian chant. ConBrio, Regensburg 2009, ISBN 3-940768-04-9 .

- Bruno Stäblein: Typeface of the unison music (= music of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Delivery 4 = music history in pictures . Vol. 3). German publishing house for music, Leipzig 1975.