Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| C91.1 | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia ICD-O 9823/3 (CLL) ICD-O 9670/3 (B-SLL) |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The chronic lymphocytic leukemia ( English chronic lymphocytic leukemia , CLL ) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia called, is a low malignant , leukemic extending B cell - Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL). It is the most common form of leukemia in the western world and occurs mainly in older people. The median age at diagnosis is around 70 years, which is why the disease is sometimes colloquially referred to as senile leukemia. In addition to CLL, the WHO classification of hematological diseases also distinguishes a sub-form, small-cell B-cell lymphoma ( English small lymphocytic lymphoma , B-SLL ). Small-cell B-cell lymphoma essentially corresponds to CLL, in which the affected B-lymphocytes are not primarily found in the bone marrow and blood, but in the lymph nodes . It can therefore be described as a non-leukemic CLL.

Epidemiology

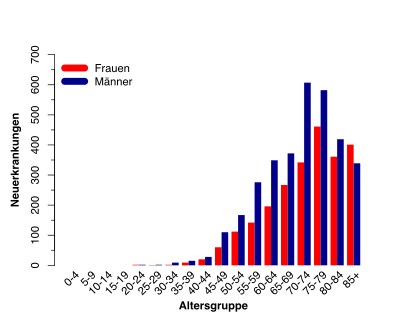

In Germany around 5,500 people develop CLL every year. With a share of 40% of newly diagnosed leukemia, CLL is the most common form of leukemia in Germany. The statistics show a slight increase in new cases in recent years. This fact is probably due on the one hand to the fact that people's life expectancy is increasing and on the other hand to the improved diagnostics and the associated consequence that more patients are diagnosed at an early stage in routine examinations.

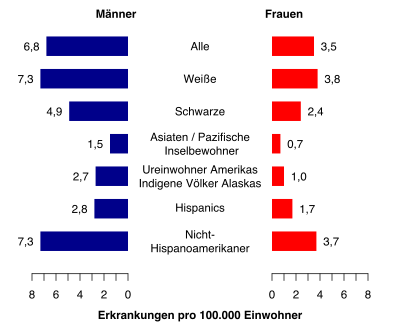

The incidence rate corresponds to approx. 6 new cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year. Men develop CLL approximately 1.4: 1 more often than women. The median age at the initial diagnosis is 70 to 75 years.

The CLL shows a clear reference to an existing genetic predisposition. There are few new cases in the Asia-Pacific region. From this perspective, the incidence rates are steadily increasing in the direction of western countries. A look at new cases in the USA shows that living conditions have less of an impact; these reflect the picture of the increasing incidence rates from the eastern to the western countries based on the multicultural population.

In addition, up to 10% of the sick have a family history of CLL. The risk of developing CLL is higher by a factor of 8.5 for direct descendants of someone with CLL compared to the rest of the population. This connection between the genetic predisposition to the diseases is not yet fully understood.

Pathogenesis

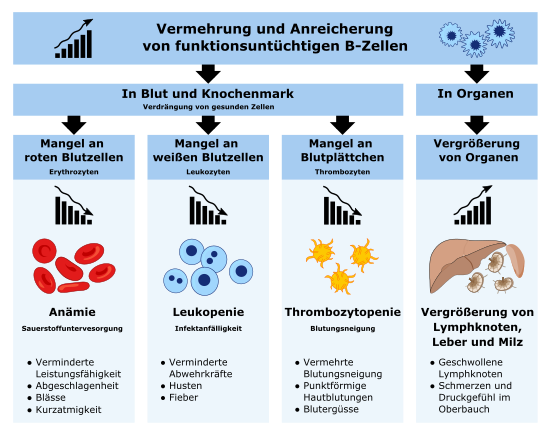

The disease leads to a clonal multiplication of mature, small-cell, but functionless B lymphocytes . The exact cause for this is still largely unknown. However, it is now assumed that genetic changes acquired in the course of life are the decisive triggers for the disease. Indications of an infectious cause, e.g. B. by viruses , does not exist yet.

Molecular genetic analysis using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) shows genetic changes in chromosomes in over 80%. The most common change is a deletion on chromosome 13 (del (13q)). Other changes include deletions of chromosome 11 (del (11q)) and 17 (del (17p)) and a trisomy 12 . These chromosome changes are of prognostic significance. Patients with del (17p) typically have a poorer prognosis. Patients with a del (13q) have a relatively favorable prognosis.

In general, CLL is a very heterogeneous clinical picture. There are patients in whom the disease takes a very benign course and does not require treatment for several years or decades. In about 1 to 2% of cases, the unusual phenomenon of partial or complete spontaneous remission also occurs in the course of the disease . But there are also patients in whom the disease shows a significantly more aggressive course. These differences in the course of the disease are the result of various interdependencies between genetic changes and the tumor microenvironment in individual patients.

diagnosis

Today, evidence of CLL is mostly discovered by chance at an early and symptom-free stage during a routine blood count. In such a case, the examination result shows a significantly increased number of leukocytes. The following blood tests are usually carried out to provide reliable evidence of the diagnosis:

- Differential blood count : The white blood cells are counted and classified according to the subgroups. A prerequisite for the clinical diagnosis of CLL is the detection of at least 5000 B-lymphocytes / µl in the peripheral blood over a period of 3 months.

- Blood smear: A drop of blood is spread thinly on a small glass plate, colored and examined under the microscope. Here, typical for CLL, there are large numbers of small and mature cell lymphocytes, and often Gumprecht's umbra in the blood smear. The Gumprecht umbra are created by the mechanical crushing of the particularly sensitive CLL lymphocytes during the preparation of the blood smear. Although they are often seen in blood smears, they are not indicative of CLL and are also found in other non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

- Immunophenotyping: Here, certain antigens on the cell surface of the lymphocytes from the peripheral blood are colored with different fluorescent antibodies and evaluated according to type, amount and combination using a flow cytometer. The different types of lymphoma have a correspondingly characteristic composition of surface antigens, which are referred to as immune phenotypes. By determining the immune phenotype, CLL can usually be reliably determined and differentiated from other leukemic non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Characteristic of CLL lymphocytes is the simultaneous presence of the T-cell antigen CD5 and the B-cell surface antigens CD19 , CD20 and CD23 , as well as the low level of the surface immunoglobulins sIgM and / or sIgD and the surface antigens CD20 and CD79b . During the immunophenotyping, the monoclonality of the B cells is confirmed by the detection of the so-called κ or λ light chain restriction.

Further examinations serve to detect the spread of CLL (chest x-ray, ultrasound examination of the abdomen).

Differential diagnosis

As a rule, CLL can be diagnosed quickly and clearly by examining the blood, since in most cases there is a typical morphology and a characteristic immune phenotype. However, if cytopenia is present or if only a small number of monoclonal B-lymphocytes are detectable in the peripheral blood, but lymphadenopathy / splenomegaly is present at the same time , or monoclonal B-lymphocytes with CD5 + expression without a phenotype typical for CLL are present, additional ones must be present Investigations are performed to safely rule out the following diagnoses:

- Mantle cell lymphoma

- B prolymphocytic leukemia

- Macroglobulinaemia Waldenström

- Cold Agglutinin Disease

- B-cell monoclonal lymphocytosis

- Richter transformation

Symptoms

The discovery of the disease is often a chance finding during a blood test as part of the diagnosis of other diseases. The following symptoms and findings occur in the course of the disease:

- Lymph node swelling

- Spleen / liver enlargement

- Skin symptoms (30 percent of cases)

- itching

- Eczema

- Mycoses

- Herpes zoster

- Skin bleeding

- nodular infiltrates

- pale skin and mucous membrane

- Parotid / parotid gland swelling ( Mikulicz syndrome )

- Leukocytosis with lymphocytosis > 10,000 / µl

- high proportion of mature lymphocytes in the bone marrow

- Antibody deficiency syndrome due to displacement of the B cells

- Detection of incomplete heat autoantibodies

- Autoimmune thrombocytopenia associated with Evans syndrome

- decreased antibodies

- increased IgM

- increased levels of thymidine kinase and β2-microglobulin

Staging and prognoses

In practice, the Binet and Rai staging are currently used. The former is mainly used in Europe, the latter in the USA. Both stages have prevailed due to their simple and inexpensive applicability. Enlargements of the lymph nodes, liver and spleen are assessed exclusively by palpation, and the hemoglobin and platelet values from the blood count are also used.

At Binet, the number of affected lymph node regions and the presence of anemia or thrombopenia are divided into three stages with different prognoses. The median survival time given is based on historical data as they were available in the 1970s and 1980s; It can be assumed that the prognoses are far more positive today due to new treatment methods.

| stage | Number of affected lymph node regions * |

Hemoglobin [g / dl] |

Platelets [G / l] |

Median survival [years] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. | <3 | ≥ 10.0 | ≥ 100.0 | > 10 |

| B. | ≥ 3 | ≥ 10.0 | ≥ 100.0 | 5-7 |

| C. | irrelevant | <10.0 | <100 | 2.5-3 |

In contrast to Binet, the Rai classification system used in the USA differentiates between five stages and a hemoglobin value of <11.0 g / dl instead of <10.0 g / dl is used as the limit value for the presence of anemia. In the course of the application, however, the Rai system was also grouped into three groups that correspond to the Binet system. Stage 0 was classified as low risk , stages I and II as medium risk and stages III and IV as high risk .

| stage |

Lymphadenopathy |

Hepato- or splenomegaly |

Hemoglobin [g / dl] |

Platelets [G / l] |

Median survival [years] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | |||||

| 0 | no | no | ≥ 11.0 | ≥ 100.0 | > 10 |

| Medium risk | |||||

| I. | ≥ 1 | no | ≥ 11.0 | ≥ 100.0 | 5-7 |

| II | irrelevant | ≥ 1 | ≥ 11.0 | ≥ 100.0 | |

| High risk | |||||

| III | irrelevant | irrelevant | <11.0 | ≥ 100.0 | 2.5 - 3 |

| IV | irrelevant | irrelevant | irrelevant | <100.0 | |

The course of the disease, however, varies greatly between the patients of a stage. A forecast index was also developed so that a better individual forecast can be created. The index takes into account the various independent influencing factors known today for a favorable or unfavorable course with an appropriate weighting. These influencing factors include the two genetic factors TP53 status and the IGHV mutation status, as well as the serum β 2 -microglobulin level as a biochemical factor and the two clinical factors disease stage and age of the patient.

| Independent forecast factor | Expression | Point value |

|---|---|---|

| TP53 status | Deleted or mutated | 4th |

| IGHV mutation status | unmutated | 2 |

| Serum β 2 -microglobulin | > 3.5 mg / L | 2 |

| Disease stage | Binet BC or Rai I-IV | 1 |

| Age | > 65 | 1 |

The scores assigned to the factors are added up to form a total score, which can be used to differentiate between four risk groups. Each of these risk groups differs in the statistically determined overall survival after five and ten years.

| Risk group | Total point value | Overall survival after 5 years [%] |

Overall survival after 10 years [%] |

Median overall survival time [months] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | 0-1 | 93.2 | 79.0 | - |

| Medium risk | 2-3 | 79.3 | 39.2 | 105 |

| High risk | 4-6 | 63.3 | 21.9 | 75 |

| Very high risk | 7-10 | 23.3 | 3.5 | 29 |

therapy

According to the current state of knowledge, CLL cannot be cured by conventional chemotherapy or antibody therapy. In principle, healing is possible through bone marrow transplantation . The therapy depends on the stage of the disease. With the rapid development of new molecular biological diagnostic methods, new drugs and treatment regimens, the recommended therapy is changing rapidly. The DKG recommends offering all patients participation in a clinical study.

The clinical classification according to Binet distinguishes between three stages. In the early stages (Binet stages A and B), treatment is usually not given unless the disease causes symptoms or progresses very quickly. These complaints can be:

- Enlargement of the spleen with symptoms

- Discomfort from growing lymph nodes

- severe general symptoms that impair quality of life (night sweats, repeated infections, fever, weight loss)

In addition, treatment is usually indicated from stage Binet C (severe anemia or thrombocytopenia).

Therapy depends on the patient's condition and the genetic mutations of the affected B lymphocytes. A combination of the chemotherapeutic agents fludarabine and cyclophosphamide with the antibody rituximab is recommended as first-line therapy for patients in good condition ("fit") . An alternative to this is the combination of bendamustine with rituximab (bendamustine has been approved for the treatment of CLL since 2010). A combination of chlorambucil or bendamustine with the antibody rituximab is recommended for patients in less good condition ("unfit") . This can be replaced by the newer antibodies ofatumumab or obinutuzumab , which recognize the same target molecule as rituximab ( CD20 ). Obinutuzumab showed a higher response rate compared to rituximab in one study. Supportive therapy is recommended for frail patients .

Also the second line therapy, i. H. Therapy for patients who relapse after initial therapy depends on the patient's condition and the genetic mutations of the tumor cells. If more than 2–3 years have passed between the primary illness and the relapse, the primary therapy can be repeated, as described in the last paragraph. Otherwise, in most patients either is Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitor Ibrutinib or a combination of PI3 kinase inhibitor Idelalisib with rituximab or anti- CD52 - antibody alemtuzumab recommended. A Rote-Hand-Brief on idelalisib was published in March 2016 (among other things not as first-line therapy !). Frail patients should receive supportive therapy. Other cytostatics can also be used in second-line therapy . Ideally, treatment should be done as part of a clinical trial.

A bone marrow or stem cell transplant can also be considered. However, the allogeneic transplant strategies in CLL are associated with high therapy-related mortality rates and are only used in selected patients. Stem cell transplants with reduced conditioning are now also being used in older patients. For the treatment of larger lymphoma one can radiation are used.

A stem cell transplant can also lead to a graft-versus-host reaction . It was evaluated whether mesenchymal stromal cells can be used for prophylaxis and therapy.

The often stressful treatment of CLL can be supplemented with physical activity to improve well-being.

literature

- Michael Hallek , Barbara Eichhorst, Daniel Catovsky (eds.): Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (= Martin Dreyling [ed.]: Hematologic Malignancies ). 1st edition. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham 2019, ISBN 978-3-03011391-9 (English).

- Michael Hallek , Barbara Eichhorst (ed.): Chronic lymphatic leukemia (= UNI-MED SCIENCE ). 5th edition. UNI-MED, Bremen 2014, ISBN 978-3-8374-2263-4 .

- Hermann Delbrück: Chronic Leukemia . Advice and help for those affected and their relatives (= advice & help ). 3. Edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-17-020470-6 .

- Guy B. Faguet (Ed.): Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia . Molecular Genetics, Biology, Diagnosis, and Management (= Gary J. Schiller [Ed.]: Contemporary Hematology ). Humana Press Inc., Totowa, New Jersey 2004, ISBN 1-58829-099-9 (English).

- Ludwig Heilmeyer , Herbert Begemann: blood and blood diseases. In: Ludwig Heilmeyer (ed.): Textbook of internal medicine. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Göttingen / Heidelberg 1955; 2nd edition ibid. 1961, pp. 376–449, here: pp. 426–428: The chronic lymphatic leukemia (chronic leukemic lymphadenosis).

Web links

- German CLL study group

- Competence network malignant lymphomas

- German Leukemia & Lymphoma Aid Foundation

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Database query - Center for cancer data. Robert Koch Institute, accessed October 26, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Cancer Stat Facts: Leukemia - Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL). National Cancer Institute, accessed November 11, 2019 .

- ^ Center for Cancer Registry Data and Society of Epidemiological Cancer Registries in Germany eV: Cancer in Germany for 2013/2014. (PDF) Robert Koch Institute, 2017, p. 128 ff. , Accessed on November 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Hermann Delbrück: Chronic Leukemia . Advice and help for those affected and their relatives (= advice & help ). 3. Edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-17-020470-6 , pp. 34 .

- ↑ a b c d Michael Hallek, Barbara Eichhorst (ed.): Chronic lymphatic leukemia (= UNI-MED SCIENCE ). 5th edition. UNI-MED, Bremen 2014, ISBN 978-3-8374-2263-4 , diagnostics.

- ↑ What is chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Frequency and age of onset. German CLL Study Group (DCLLSG), accessed on November 15, 2019 .

- ^ Kurt Possinger, Anne Regierer (ed.): Specialist in hematology and oncology. Elsevier, Munich, ISBN 978-3-437-23770-6 .

- ^ A b Michael Hallek , Barbara Eichhorst, Daniel Catovsky (eds.): Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (= Martin Dreyling [ed.]: Hematologic Malignancies ). 1st edition. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham 2019, ISBN 978-3-03011391-9 , Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Who, How, and Where? (English).

- ↑ Marwan Kwok, Ceri Oldreive, Andy C. Rawstron, Anshita Goel, Grigorios Papatzikas, Rhiannon E. Jones, Samantha Drennan, Angelo Agathanggelou, Archana Sharma-Oates, Paul Evans, Edward Smith, Surita Dalal, Jingwen Mao, Robert Hollows, Naheema Gordon, Mayumi Hamada, Nicholas J. Davies, Helen Parry, Andrew D. Beggs, Thalha Munir, Paul Moreton, Shankara Paneesha, Guy Pratt, A. Malcolm R. Taylor, Francesco Forconi, Duncan M. Baird, Jean-Baptiste Cazier, Paul Moss, Peter Hillmen, Tatjana Stankovic: Integrative analysis of spontaneous CLL regression highlights genetic and microenvironmental interdependency in CLL. In: Blood - Volume 135, Issue 6. American Society of Hematology, February 6, 2020, pp. 411-428 , accessed February 8, 2020 .

- ↑ a b c Michael Hallek, Bruce D. Cheson, Daniel Catovsky, Federico Caligaris-Cappio, Guillermo Dighiero, Hartmut Döhner, Peter Hillmen, Michael Keating, Emili Montserrat, Nicholas Chiorazzi, Stephan Stilgenbauer, Kanti R. Rai, John C. Byrd , Barbara Eichhorst, Susan O'Brien, Tadeusz Robak, John F. Seymour, Thomas J. Kipps: iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. In: Blood - Volume 131, Issue 25. American Society of Hematology, June 21, 2018, accessed October 20, 2019 .

- ↑ Michael Hallek , Barbara Eichhorst, Daniel Catovsky (eds.): Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (= Martin Dreyling [ed.]: Hematologic Malignancies ). 1st edition. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham 2019, ISBN 978-3-03011391-9 , Laboratory Diagnosis of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (English).

- ↑ JL Binet: A new prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukemia derived from a multivariate survival analysis. (pdf) In: Cancer - Volume 48 Issue 1. Wiley-Blackwell, July 1, 1981, accessed on October 12, 2019 (eng).

- ↑ a b c d S3-guideline on diagnosis, therapy and follow-up care for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). (PDF) Oncology Guideline Program of the Working Group of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany, German Cancer Society (DKG) and German Cancer Aid (DKH), March 2018, pp. 33-35 , accessed on October 18, 2019 .

- ↑ a b The International CLL-IPI working group: An international prognostic index for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL-IPI): a meta-analysis of individual patient data. In: The Lancet Oncology . tape 17 , no. 6 . Elsevier, June 2016, ISSN 1474-5488 , p. 779-790 , doi : 10.1016 / S1470-2045 (16) 30029-8 , PMID 27185642 (English).

- ^ A b Michael Hallek , Barbara Eichhorst, Daniel Catovsky (eds.): Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (= Martin Dreyling [ed.]: Hematologic Malignancies ). 1st edition. Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham 2019, ISBN 978-3-03011391-9 , Prognostic Markers (English).

- ↑ a b Leading specialist society: German Society for Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO): S3 guideline on diagnostics, therapy and aftercare for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) long version 1.0 - March 2018 AWMF register number: 018-032OL. Oncology guideline program of the Working Group of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF), German Cancer Society (DKG) and German Cancer Aid (DKH)., 2018, accessed on June 11, 2019 .

- ↑ Valentin Goede, Kirsten Fischer, Raymonde Busch, Anja Engelke, Barbara Eichhorst, Clemens M. Wendtner, Tatiana Chagorova, Javier de la Serna, Marie-Sarah Dilhuydy, Thomas Illmer, Stephen Opat, Carolyn J. Owen, Olga Samoylova, Karl- Anton Kreuzer, Stephan Stilgenbauer, Hartmut Döhner, Anton W. Langerak, Matthias Ritgen, Michael Kneba, Elina Asikanius, Kathryn Humphrey, Michael Wenger, Michael Hallek: Obinutuzumab plus Chlorambucil in Patients with CLL and Coexisting Conditions. In: New England Journal of Medicine . 2014, 370: 1101-1110, doi: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1313984 .

- ↑ Ibrutinib: New kinase inhibitor in blood cancer. Pharmaceutical newspaper, September 24, 2014, accessed September 5, 2015 .

- ↑ Leukemia and Lymphoma: New drug approved. Pharmaceutical newspaper, October 21, 2014, accessed September 5, 2015 .

- ↑ Restrictions on the use of idelalisib for the treatment of CLL , RHB Gilead, March 23, 2016, accessed March 24, 2016.

- ↑ IDW-Online September 20, 2011 .

- ↑ Sheila A Fisher, Antony Cutler, Carolyn Doree, Susan J Brunskill, Simon J Stanworth: Mesenchymal stromal cells as treatment or prophylaxis for acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease in haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients with a haematological condition . In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . January 30, 2019, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD009768.pub2 ( wiley.com [accessed August 25, 2020]).

- ↑ Linus Knips, Nils Bergenthal, Fiona Streckmann, Ina Monsef, Thomas Elter: Aerobic physical exercise for adult patients with haematological malignancies . In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . January 31, 2019, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD009075.pub3 ( wiley.com [accessed August 25, 2020]).