Cyriac battle

| date | August 8, 1266 |

|---|---|

| place | Mühlberg between Sulzfeld am Main and Kitzingen |

| Casus Belli | Conflict over the election of a bishop of Würzburg |

| output | Victory of the Würzburg Cathedral Chapter and the Hohenlohe |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

|

Cathedral dean Berthold von Sternberg |

Count Hermann I von Henneberg |

| Troop strength | |

| approx. 600 citizens of Würzburg, 50 mounted | 300 to 600 riders |

The Cyriakus Battle (also the Battle of Cyriakus Day and the Battle of Kitzingen ) was a warlike conflict between the Würzburg Cathedral Chapter and the Lords of Henneberg on August 8, 1266. The two parties were at odds over the candidates for the Würzburg bishopric. While the battle was originally regarded as one of the largest of the Middle Ages in Franconia , the prevailing opinion today is that it was just a small battle of arms.

prehistory

The prehistory to the Battle of Cyriakus reflects the conflicts that were also virulent in the Holy Roman Empire . With the deposition of the last Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick II by Pope Innocent IV , the interregnum began in 1245 , in which the princes of the empire strived for more power independent of central authority. The Würzburg bishop Hermann I von Lobdeburg succeeded in expanding his territory. With the acquisition of Botenlauben Castle near Kissingen in 1234, the bishop entered the sphere of influence of the Counts of Henneberg.

The counts had provided the powerful Würzburg burgrave for centuries and were eventually ousted by the bishops. Nevertheless, the Henneberger were the most powerful noble family in northern Franconia and were able to expand their possessions again and again at the expense of the prince-bishopric. Under Bishop Iring von Reinstein-Homburg , two parties emerged in Würzburg that either supported the growing influence of the Hennebergs or opposed them.

At the same time, the Hennebergers pushed the conflict with the Lords of Hohenlohe forward. Count Hermann I. von Henneberg and his brothers refused to pay their sister Kunigunde's dowry to Albrecht von Hohenlohe after she died. A short time later, Uffenheim Castle was awarded to Hermann von Henneberg as a fief. He thereby curtailed the Hohenlohe's sphere of influence and penetrated to their headquarters.

The simmering conflicts emerged during the election of bishops after Iring's death in 1265. The Würzburg cathedral chapter was divided. A minority of the electorate preferred the candidate Berthold von Henneberg . Most of the members of the cathedral chapter, led by cathedral dean Berthold von Sternberg, supported the election of the cathedral provost Poppo von Trimberg . After the election did not bring any result, the conflict was fought like a war.

The citizens of Würzburg could be won against the Henneberg by the dean of the cathedral. They called their relatives, the Counts of Castell , to help and used their area in the Steigerwald foreland as a deployment area for their troops. On August 6, 1266, the cathedral chapter agreed an aid contract with the Lords of Weinsberg , who also went to the field against the Hennebergers. Other noble families were probably drawn to the chapter's side with such contracts.

Course of the battle

On August 7, 1266, the troops of the cathedral chapter left the city of Würzburg from the Rennwegtor and marched in the direction of Castell . The town's craftsmen had been armed with light weapons. In addition, several mounted sons of the wealthier citizens strengthened the Würzburg army. Overall, it can be assumed that around 600 foot soldiers and 50 horsemen fought on the side of the cathedral chapter. In addition, the soldiers of the smaller noble families moved out.

The Hennebergers went into battle with 300 to 600 horses and an army consisting mainly of knights . In the highly penal historiography , wrong information was often given, so one spoke of over 1400 knights, of which only 150 were able to escape. The higher numbers served to underpin the victory of the cathedral chapter and to increase the threat posed by the Hennebergers.

The Counts of Henneberg and their Casteller relatives left the Steigerwaldort Castell on the morning of August 8th and probably planned to reach the height between Repperndorf and Biebelried and to field the chapter troops there in an open field battle. To do this, they had to cross the Main near Kitzingen . The town of Kitzingen with its stone bridge, however, was in the hands of the Hohenlohe and so one passed the Main further south near Sulzfeld .

There the soldiers of the cathedral chapter were already waiting for the approaching enemies and probably involved them in a battle while they were crossing the Main. Then the actual battle began on the so-called Mühlberg. The name first appeared in 1448 when a mill was built there. Even then, it was associated with the battle. The landscape between Sulzfeld and Kitzingen is rugged and offered the light troops of the chapter better opportunities to strike.

Overall, the battle at the vineyard- occupied Mühlberg lasted five to six hours. In the older literature it was assumed that the fighting had extended to Kitzingen. It is more likely, however, that the battle was confined to the slope. A legend reported by the Bavarian nobleman Tannhäuser, who is said to have changed sides during the battle, also lacks reality.

The Hennebergers probably broke off the battle after their losses became too high. Exact numbers of favors are not available because here, too, the highly penal historiography with exaggerated information was decisive for a long time. In the 20th century it was assumed that three Counts Castell were dead, 500 soldiers killed and 200 captured. It is more likely, however, that not a single member of the sexes involved died because no names appeared in the necrologies .

consequences

Although the battle ended in defeat for the Counts of Henneberg, the dispute over the election of the bishop was by no means decided afterwards. This is one of the reasons why it can be assumed that it was just a minor battle and that it was not, as the older literature claims, one of the greatest battles of the Franconian Middle Ages . The battle of arms was soon named the Cyriac Battle because it took place on the day of the saint .

Meanwhile, the conflict in the cathedral chapter persisted and the two candidates insisted on their claim. The election, which was carried out in July 1267, brought an unclear result, so that both Poppo von Trimberg and Berthold von Henneberg saw themselves as legitimate bishops. The two warring camps started a war that would last over seven years. After the death of Poppo von Trimberg, Berthold von Henneberg was sealed as bishop.

However, the cathedral dean Berthold von Sternberg, the military leader of the troops of the cathedral chapter in the battle, initiated a process against the bishop in Rome, who in his eyes was illegitimate. Finally Pope Gregor X. Berthold von Henneberg relieved of his office and installed Berthold von Sternberg . Henneberg never accepted the impeachment and held the title of bishop until his death in 1312.

In the long term, however, the winners of the Battle of Cyriac achieved their goals. The Hennebergers were pushed back to their home areas on the northern edge of the bishopric and later no longer played a role in the occupation of the bishopric, but almost completely lost their influence on Franconia. The Counts of Castell withdrew to their estates on the edge of the Steigerwald and fell away as territorial lords along the Main .

reception

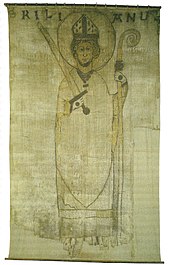

The battle on Cyriakus Day was often referred to in the history of the Würzburg monastery. So was the banner with St. Kilian , which was probably made shortly before the confrontation, during the battle above the Mühlberges blew on a flag cars and is the oldest, got field label in Germany, every year on August 8, in a solemn procession to the city wall was borne by Würzburg and was named "Cyriakuspanier". These parades took place in the 18th century. Today the banner is in the Museum für Franken .

The citizens of Würzburg, who had also fought in the battle, bought a bell for the Marienkapelle in Würzburg. This "Cyriacus bell" also rang on the day of the battle. It was destroyed in 1945. In the 16th century, the episcopal chronicle of Lorenz Fries was devoted to the battle, he made a drawing about the conflict. The battlefield itself, today in the district of Sulzfeld am Main, houses the Sulzfelder Cyriakusberg vineyard . In addition, several hiking trails were named after the battle.

Many literary embellishments and stories that appeared later are also typical of the reception of the battle. Friedrich Wilhelm Pistorius added a proverb that was coined after the battle to his collection of proverbs in 1715 and 1741. It refers to the defeat of the Counts of Castell from the point of view of the Würzburg citizens. It reads: "Today we have a public holiday, but at Castell they muck the stalls (...)".

literature

- Klaus Arnold : The Kitzingen Cyriac Battle of 1266 . In: Mainfränkisches Jahrbuch für Geschichte und Kunst 69 (2017), pp. 161–191.

- Marianne Erben: The Cyriakus banner saw the Hennebergers fighting . In: Franconia. Journal for Franconian regional studies and culture, 48th cent. Würzburg 1996. pp. 159-161 ( online ).

- Wilhelm Füßlein: Two decades of Würzburg monastery, town and state history 1254–1275 (= New Contributions to the History of German Antiquity, Issue No. 20) . Meiningen 1926 ( online ).

- Ernst Kemmeter: The Cyriakus Battle 1266 . In: In the spell of the Schwanberg 1967. Heimat-Jahrbuch for the district of Kitzingen . Kitzingen 1967. pp. 117-123.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kemmeter, Ernst: The Cyriakus Battle 1266 . P. 119.

- ↑ Kemmeter, Ernst: The Cyriakus Battle 1266 . P. 120.

- ↑ Füßlein, Wilhelm: Two decades würzburgischer collegiate, town and country's history 1254-1275 . P. 133.

- ↑ Füßlein, Wilhelm: Two decades würzburgischer collegiate, town and country's history from 1254 to 1275 . P. 134.

- ↑ Kemmeter, Ernst: The Cyriakus Battle 1266 . P. 118.

- ↑ Füßlein, Wilhelm: Two decades würzburgischer collegiate, town and country's history from 1254 to 1275 . P. 140 f.

- ↑ Kemmeter, Ernst: The Cyriakus Battle 1266 . P. 123.

- ^ Arnold, Klaus: The Kitzinger Cyriakus Battle of 1266 . P. 171 f.

- ↑ Erben, Marianne: Das Cyriakusbanner . P. 160 f.

- ^ Arnold, Klaus: The Kitzinger Cyriakus Battle of 1266 . P. 167.