Dalmatian

| Dalmatian | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| FCI Standard No. 153 | ||

|

||

| Origin : | ||

| Alternative names: |

Dalmatinac |

|

| Withers height: |

Males 56-62 cm. |

|

| Weight: |

Male 27–32 kg, |

|

| List of domestic dogs | ||

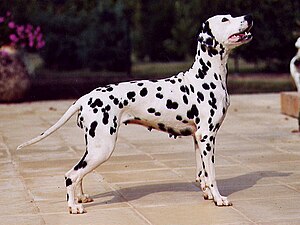

The Dalmatian ( Croatian Dalmatinac ) is a breed of dogs from Croatia recognized by the FCI ( FCI Group 6, Section 3, Standard No. 153 ).

description

The Dalmatian is a medium-sized to large, well-proportioned, spotted, strong, lively, very showy dog . His balanced, slim body has a strong back with an even, straight back line. The Dalmatian has muscular shoulders, a long but not too wide chest, and an elegant neck. Its lop ears are moderately large, set high and lie close to the head. Its eyes are round and should usually be dark brown on specimens with black spots. Liver-brown dogs should have amber eyes. The tail of the Dalmatian is sickle-shaped. It is long, gradually narrowing, and extends to the hocks. The fur is unique among the dog breeds: white with black or brown clearly outlined spots. It owes this coloration to a so-called piebald gene.

The coat, which has the basic color white and black or liver-brown spots, is short, hard and dense and looks smooth and shiny. The spots should not run into each other and should be round and clearly delimited. This dog, which is symmetrical in its outlines, has no coarseness, has a height at the withers of 56–61 cm and a weight of 24–32 kg.

The puppies are usually born white and the spots only show up after 10 to 14 days. Only in adulthood, around one year old, does the spotting no longer change. Animals that have black spots (plates) from birth are excluded from breeding. Plates are usually larger than the other spots and often appear on the head, there often on the eye (periocular plate) or on the ears.

In the meantime, many advocate including such dogs in breeding, since the incidence of deafness in animals (in dogs in general, not only in Dalmatians) increases proportionally with the proportion of white in the coat, with the proportion of white in the head area being particularly important.

Blue eyes, bilateral or one-sided (bicolor) are also faults that exclude breeding, as such dogs pass on more deafness. Other breeding faults include lemon-colored dogs or those with brown and black spots (tricolor). It is recommended to exclude deaf and, ideally, one-sided deaf dogs from breeding.

Essence

Dalmatians show a very friendly nature. They are sometimes seen as a lively family dog, but they are very adaptable. They are extremely sensitive, usually very cuddly and should be brought up with love and praise and not with severity. It can happen that the active dog shows behavior problems if he is permanently under-challenged.

attitude

The Dalmatian was bred for endurance; his job was to run alongside carriages to protect against robbers, strange dogs or wild animals. Accordingly, he feels comfortable on long runs and is not suitable for a sofa dog. The Dalmatian needs at least two, better three to four hours of exercise a day, which cannot be replaced by a garden.

For this intelligent dog, not only physical but also psychological mobility and support are of great importance. He learns small tricks with enthusiasm. Search games of all kinds offer training for the mind. It is well suited for dog sports such as agility or obedience .

history

The first images of Dalmatian-like dogs can already be found in Egyptian pharaohs tombs. Some speculations assume that the Dalmatian was introduced from India via Egypt and Greece to the western Mediterranean area and from there to France and England. In England he was very popular as a coach companion dog during the Victorian era. He later became the mascot of the New York Fire Department by running ahead of the horse-drawn fire engine as a living siren in the 19th century.

There are several theories as to where the name Dalmatian comes from; one theory is derived from the Croatian coastal region of Dalmatia .

health

deafness

The first scientific study of deafness in Dalmatians appeared in 1896, but as early as 1769, Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon had linked deafness in dogs with white fur in the fifth volume of his Histoire naturelle générale et particulière . In a study carried out in Germany and published in 2000, 19.7% of the 1,899 Dalmatians examined were found to be deaf. An American study from 1992 found 29.7% deafness among 1,031 Dalmatians; this proportion was confirmed in 2011 using data from studies published between 2004 and 2011.

The main form is the congenital sensorineural deafness, the specific destruction by neuro- epithelial structures is characterized (= sense cell structures in the upper layers of the skin) of the inner ear. The damage develops unilaterally or bilaterally as a result of a disruption of pigment formation after birth while the puppy's ears and eyes are still closed, and is usually visible in the first six to eight weeks of life. The disease is more common in blue-eyed dogs and less common in dogs with plate drawings. In 2000, a major autosomal recessive gene was found to be responsible for the disease. Nevertheless (as of 2011) neither the exact number of genes involved is known, nor is a gene causing deafness precisely identified. However, in the last few years it has been possible to narrow it down to certain regions of the genome, which are now being examined more closely.

Due to the complex inheritance of deafness with several genes involved, in contrast to numerous other hereditary diseases in dogs , no genetic test for the predisposition to deafness has yet been developed. To make matters worse, deaf dogs can have two physically healthy parents. On the other hand, two deaf parents can produce hearing offspring. Deafness is named as an exclusive fault in the FCI breed standard, but without a clear definition of whether one-sided deafness is also an exclusion criterion. The exclusion of affected animals from breeding is not enough to significantly reduce the occurrence of deafness in the Dalmatian. In contrast to the AKC breed standard, blue eyes are also an exclusive fault in the FCI.

Dalmatian syndrome

Due to a genetically predisposed metabolic defect, urinary stones (bladder / kidney stones) form more often in Dalmatians than in other dog breeds. The terms Dalmatian syndrome or Dalmatian error are common for this. The term hyperuricosuria is used more generally . The condition is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. The triggering change in the genetic makeup of several dog breeds is known, but until a few years ago, all dogs of the Dalmatians were genetically pure for the mutation.

Uric acid level

The enzyme uricase , which is found in liver cells, converts in all mammals except humans and human-like , uric acid (a breakdown product of purines ) in allantoin to. This breakdown process is disturbed in Dalmatians, they have a defective uric acid transport system in the liver, which means that most of the uric acid does not come into contact with the enzyme. In addition, uric acid reabsorption in the renal tubules of the Dalmatian is restricted. Compared to other dogs, he excretes more than ten times the amount of uric acid with the urine every day (200–800 mg instead of 15–50 mg).

Clinical symptoms

A consequence of the increased uric acid level can be a form of dermatitis typical for Dalmatians , the formation of urinary stones usually in the bladder, but also in the kidneys or urinary tract is another. Uric acid is sparingly soluble in water and tends to crystallize , especially as the salt urate . Most of the time, ammonium urate crystals appear ( ammonium as a breakdown product of amino acids). Although until a few years ago all pure-bred Dalmatians had the genetically determined high uric acid level in the urine, not all dogs developed urinary stones. Therefore, it is certain that there are other causes of the formation of urinary stones. Males get sick many times more often than bitches; One reason for this is believed to be that the more favorable structure of the urinary organs in the bitch enables the drainage of small bladder stones, which in the male continue to grow and cause clinical symptoms. On the basis of studies published so far, no information can be given about the risk of an individual Dalmatian getting sick with urinary stones.

nutrition

In the diet of the Dalmatian, attention should be paid to low-purine food. A low-purine diet, by reducing crude protein in the diet, either by feeding special diet foods or by avoiding beef and offal, lowers the uric acid level, which nevertheless remains higher than in other dog breeds. Feeding a commercial dry feed , but with a low crude protein content of 15%, has proven to be just as effective as feeding special diet feeds. Canned food is judged unfavorably because of the higher meat content. The development of urinary stones can also be influenced by the housing conditions, so Dalmatians develop urinary stones less often if they only receive daily feeding in the afternoon or if they have frequent opportunities to mark and urinate.

Genetic cause

It was not until 2005 that a molecular genetic investigation was able to prove that the mechanism that causes an increased uric acid level in the urine in Dalmatians is different from a mutation that occurs in humans . The hyperuricosuria of the Dalmatian is caused by mutations in the SLC2A9 gene. The defect is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, all Dalmatians - with the exception of the breeding line that has emerged from a cross with a Pointer since 1973 - are pure-breeding carriers of the mutation. Therefore, all Dalmatians also have hyperuricosuria, that is, the increased concentration of uric acid in the urine. The genetic defect occurs not only in Dalmatians, but also in Russian terriers , bulldogs and some other dog breeds. However, not all dogs are affected in these breeds, so that the mating of gene carriers can be avoided.

Intersection of a healthy gene

History and start of the project

In 1973 the American geneticist Robert H. Schaible crossed a Dalmatian dog with a pointer male. Already in the early 20th century there had been repeated crossings of Dalmatians with other dog breeds , also over several generations, in order to research the occurrence of hyperuricosuria in crossbreeding products. It was already known that the disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. Schaible could assume that the crossbreeding of a single genetically healthy dog with the dominant healthy gene would produce a number of healthy dogs, from the first crossing of a Dalmatian (genetic uu) with a genetically completely healthy dog of any other breed (UU) were only physically healthy carriers of the genetic defect (possibly) to be expected. The further mating of these dogs with pure-bred Dalmatians as carriers of the genetic defect would statistically result in 25% pure-blooded healthy dogs (UU), 50% physically healthy carriers of the genetic defect (possibly), and 25 pure-blooded carriers of the genetic defect (see below). The offspring of the cross, if they did not belong to the expected 25% pure-blooded carriers of the genetic defect, still have the hoped-for low uric acid levels in the urine.

Resistances

In the 1980s and up to 2011, Schaible encountered resistance from organized dog breeders and the stud book associations with his concern to combat the genetic defect of the Dalmatian by crossing into another breed . In 1981 two of the dogs bred by the American Kennel Club (AKC) were included in the studbook as pure-bred Dalmatians, but in the same year, after an intervention by the Dalmatian Club of America, the AKC decided not to register their offspring.

In the first half of the 20th century it was still quite common among breeders to crossbreed dogs of other breeds in an existing breed in order to “refresh blood” or to change certain mostly physical characteristics of the pedigree dogs. Since then, the situation had changed to such an extent that it seemed fundamentally unthinkable for dog breeders to cross a pedigree dog with a representative of another breed. A dog breed was and is not only defined by the mostly physical characteristics specified in the breed standards , but also by "closed" stud books that only allow dogs whose parents and ancestors have been registered in the stud book for several generations.

Success of crossbreeding

Regardless of this, Schaible continued to breed together with other dog breeders, but after the one-time crossing of a Dalmatian with a pointer, he limited himself to crossing the offspring of this mating with purebred Dalmatians and, at a later point in time, with each other. By 2010, "LUA-Dalmatians" (for Low Urinary Acid ) had been bred for more than 12 generations , with thousands of purebred Dalmatians recognized by the American Kennel Club and a pointer in their lineage. The dogs met due to the small amount of genetic material of the pointer and externally to the image of a Dalmatian.

The genetic comparison of 27 LUA-Dalmatians with Dalmatians from the USA and Great Britain as well as other dog breeds showed that the Dalmatians from both countries of origin show genetic differences and form groups that can be distinguished from one another, that the LUA-Dalmatians and the dogs from the USA together form one group and that the LUA Dalmatians do not form a group with pointers or with any other breed of dog. The breeding records of the LUA Dalmatians were kept completely and a urine test, later also a genetic test , was carried out before mating in order to be able to certify the dogs' genetic health. However, these dogs were refused entry into the AKC's studbooks, but they could be registered with the United Kennel Club , another American breeders' association.

Registration of LUA Dalmatians

After an almost complete breakdown of the breed around 2005, there were around 30 LUA Dalmatians in the USA in 2007. Through repeated efforts over many years, which included surveys of members with initially negative results both in the studbook-keeping Dalmatian Club of the USA and in the American Kennel Club as the umbrella organization, the studbooks were opened in 2011 - also retrospectively - for those LUA Dalmatians who were able to prove their descent without gaps and corresponded to the breed standard of the Dalmatian. Since then, breeders of the Dalmatian have been free to include LUA-Dalmatians in their breeding.

Since the American Kennel Club has agreed with the British Kennel Club and the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI) the mutual recognition of the stud book entries, this regulation applies worldwide to the dogs registered by the AKC and their also registered offspring. In 2009 two imported bitches and one male had already received a restricted registration in Great Britain. In 2012 there were five litters of recognized LUA Dalmatians in Europe, in France, Great Britain and Germany. A German puppy came to Finland and an LUA stud dog is used in Italy.

The voluntary crossbreeding of LUA-Dalmatians has the indirect effect of preventing a threatening bottle neck effect in the Dalmatian gene pool. If too many matings are carried out with at least one LUA Dalmatian within a short period of time, this would greatly reduce genetic diversity and raise the risk of other genetic defects occurring. It can currently be assumed that the removal of the defective gene from the Dalmatian population will not take place promptly, but rather that the breed will recover over a long period of time.

Dalmatian leukodystrophy

The Dalmatian leukodystrophy is a rare, hereditary disorder of the central nervous system with visual and movement disorders occurring in young animals and quickly leads to loss of vision and to incoordination in the movement.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Sheila Schmutz: Dog Coat Color Genetics. 2014 http://homepage.usask.ca/~schmutz/dogspots.html

- ↑ a b Fédération Cynologiqie Internationale (ed.): Breed standard No. 153 of the FCI: Dalmatians (PDF) , accessed on September 1, 2013.

- ↑ dalmatineronline.de

- ↑ Bernhard Rawitz: Hearing organ and brain of a white dog with blue eyes. In: Gustav Schwalbe (Ed.): Morphological work. Volume 6, Gustav Fischer, Jena 1896, pp. 545–553. ( online or online PDF 51.9 MB, accessed on August 31, 2013)

- ↑ a b c George M. Strain: Deafness in Dogs and Cats. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, Oxfordshire 2011, ISBN 978-1-84593-937-3 .

- ↑ Simone G. Rak, O. Distl, I. Nolte, J. Bullerdiek: Molecular genetic investigation of the congenital deafness in the Dalmatian. In: Society for the Promotion of Cynological Research (ed.): Circular 13 (2001) pp. 41–46.

- ↑ a b Ottmar Distl: Molecular genetic elucidation of the congenital sensorineural deafness in the Dalmatian. November 14, 2007, ( online on the website of the Club for Dalmatian Friends, accessed on August 31, 2013.)

- ↑ American Kennel Club (ed.): Dalmatian. Breed standard. ( online or online PDF 18 kB, accessed on September 1, 2013)

- ↑ Ekkehard Wiesner, Regine Ribbeck (ed.): Lexicon of Veterinary Medicine . 4th, completely revised edition. Enke, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-7773-1459-5 , p. 310 .

- ↑ a b Hasan Albasan et al: Evaluation of the association between sex and risk of forming urate uroliths in Dalmatians. In: Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. vol. 227, no. 4, August 15, 2005, ISSN 0003-1488 , pp. 565-569.

- ↑ Otto Folin, Hilding Berglund, Clifford Derick: The uric acid problem. An experimental study on animals and man, including gouty subjects. In: The Journal of Biological Chemistry. vol. 60, no. 2, 1924, pp. 361-471. ( online PDF 6,095 kB, accessed on September 1, 2013)

- ^ A b Gabriella Foschi: Nucleotide metabolism and Urate excretion in the Dalmatian dog breed. Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala 2008. ( online PDF ( Memento of the original dated August 25, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and Archive link according to instructions and then remove this note. 222 kB, accessed on September 1, 2013)

- ^ A b Robert H. Schaible: A Dalmatian Study. The Genetic Correction of Health Problems. In: The AKC Gazette. April 1981. ( (online) ( Memento of the original from March 11, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note. , Accessed on 1 April 1981 . September 2013)

- ↑ Wendy Y. Brown, BA Vanselow, SW Walkden – Brown: One dog's meat is another dog's poison - nutrition in the Dalmatian dog. In: Recent Advances in Animal Nutrition in Australia. vol. 14, 2003. ( online PDF 1,140 kB, accessed on September 1, 2013)

- ↑ Danika Bannasch et al: Mutations in the SLC2A9 Gene Cause Hyperuricosuria and Hyperuricemia in the Dog. In: PLoS Genetics. vol. 4, no. 11, 2008, article e1000246, doi: 10.1371 / journal.pgen.1000246 . ( online PDF 522 kB, accessed on September 1, 2013)

- ↑ Noa Safra et al: Exclusion of Urate Oxidase as a Candidate Gene for Hyperuricosuria in the Dalmatian Dog Using an Interbreed Backcross. In: Journal of Heredity. 96, 2005, pp. 750-754, doi: 10.1093 / jhered / esi078 . ( online PDF 90 kB, accessed on September 1, 2013)

- ↑ a b c American Kennel Club, AKC Canine Health, Welfare Advisory Committee: Executive Summary & Recommendation - LUA Dalmatians. unpublished statement, approx. 2010. ( online PDF 22 kB, accessed on September 1, 2013)

- ↑ Nili Karmi et al .: Estimated frequency of the canine hyperuricosuria mutation in different dog breeds. In: Journal of veterinary internal medicine / American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine. Volume 24, number 6, 2010 Nov-Dec, pp. 1337-1342, ISSN 0891-6640 , doi: 10.1111 / j.1939-1676.2010.0631.x . PMID 21054540 . ( online PDF 111 kB, accessed September 1, 2013)

- ↑ Cathryn Mellersh: DNA testing and domestic dogs. In: Mammalian Genome. 23, 2012, pp. 109-123, doi: 10.1007 / s00335-011-9365-z . ( online PDF 205 kB , accessed September 1, 2013)

- ^ CE Keeler: The Inheritance of Predisposition to Renal Calculi in the Dalmatian. In: Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. vol. 96, 1940, ISSN 0003-1488 , pp. 507-510.

- ^ Herbert Onslow: The Relation between Uric Acid and Allantoin Excretion in Hybrids of the Dalmatian Hound. In: Biochemical Journal. vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 334-340, PMC 1259350 (free full text).

- ↑ Herbert Onslow: Uric Acid and allantoin excretion among Offspring of Dalmatian hybrid. In: Biochemical Journal. vol. 17, no. 4-5, pp. 564-568, PMC 1263924 (free full text).

- ^ A b Mary – Lynn Jensen: Dalmatian Backcross Project. Past, Present and Future. In: Spotter. Fall 2006, pp. 44–46 (magazine of the Dalmatian Club of America) online PDF 296 kB, accessed on September 1, 2013.

- ^ Ed Petit: Defending an ancient breed. In: Spotter. Summer 2007, p. 112 (an opposite position to the crossing) online PDF 259 kB, accessed on September 1, 2013.

- ^ A b c Denise Powell: The Dalmatian Pointer Backcross Project. Overcoming 20th Century Attitude About Crossbreeding. In: E Dalmatians. vol. 5, no. 1, Feb / Mar 2012, p. 22 online PDF 92 kB, accessed on September 1, 2013.

- ↑ Elaine A. Ostrander : Genetics and the Shape of Dogs. In: American Scientist. vol. 95, no. 5, September-October 2007, ISSN 0003-0996 , pp. 406-413.

- ^ American Kennel Club Health, Welfare Advisory Panel: Molecular Genetic Analysis of Backcross Dalmatians Compared to AKC Dalmatians, UK Dalmatians, Pointers, and Other Breeds. unpublished statement, April 30, 2010 ( online PDF 607 kB, accessed September 1, 2013)

- ↑ Robert H. Schaible: Back Cross Project: Long-standing issues. In: Spotter. Winter 2006, p. 34 (magazine of the Dalmatian Club of America) ( online PDF 34 kB, accessed on September 1, 2013)

- ↑ Dominique Vincent: Dalmatia's LUA. Victoire sur une maladie génétique. In: Cynophilie française. 2 ème trimestre, 2012, ISSN 1251-3482 , pp. 30-31.

Web links

- Breed standard No. 153 of the FCI: Dalmatians (PDF)

- Link catalog on the topic of Dalmatians at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )