Deddington Castle

Deddington Castle is an Outbound castle in the village of Deddington in the English county of Oxfordshire . The castle was built after the Norman conquest of England in 1066 on a rich Anglo-Saxon estate at the behest of Bishop Odo of Bayeux . The motte consisted of a central mound and two castle courtyards, so that the region could be administered from there and it represented a strong military base in the event of an Anglo-Saxon revolt. The bishop's lands were expropriated after an unsuccessful revolt against King William II in 1088 and Deddington Castle came back under royal control. The Anglo-Norman nobleman William de Chesney acquired the castle in the 12th century and had it rebuilt in stone, with a stone curtain wall being drawn around the main castle with the fortified tower , gatehouse and residential buildings.

After De Chesney's death, his descendants fought over control of the castle at court and so King Johann Ohneland took Deddington Castle into his possession several times at the beginning of the 13th century. Eventually he confirmed that the castle was owned by the Dive family and that family held ownership of it for the next 1½ century. In 1281 the castle was stormed by a group of men who broke open the gates, and in 1312 the royal favorite Piers Gaveston may have been held there by his enemies shortly before his execution. From the 13th century onwards, Deddington Castle fell into disrepair and contemporaries soon described it as "ruined" and "weak". In 1364 Dean and Canons of Windsor bought the castle and started selling the building blocks. The remains of the castle served a number of accounts, according to both the royalists and the parliamentarians, in the 17th century English civil war .

In the 19th century, Deddington Castle was rebuilt as a sports facility for the local nobility. Then it was sold to the Deddington local government, which wanted to have tennis courts built in the inner castle in 1947. After the discovery of medieval remains and a subsequent archaeological investigation, these plans were abandoned and the western half of the castle ruins became a public park. In the 21st century, English Heritage managed the inner castle, while the eastern half of the former castle continued to be used for agriculture. The property is a Scheduled Monument .

history

11th century

Deddington Castle had Bishop Odo of Bayeux built in the village of Deddington shortly after the Norman conquest of England. Deddington was then one of the largest settlements in Oxfordshire and the castle grounds were previously occupied by the Anglo-Saxons, who presumably used it to manage their lands. Odo von Bayeux was the half-brother of King William the Conqueror , who gave him extensive lands after the invasion, which were spread over 22 counties. Deddington was one of the richest manors of Odo of Bayeux and was at the center of his lands in Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire . The castle was believed to have been built to serve as the caput or administrative center of his lands in the region and as a military base in the event of an Anglo-Saxon revolt.

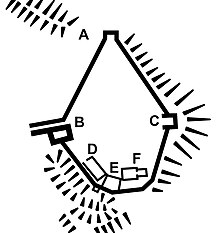

The castle then stood on the east side of the main part of the settlement, on the other side like the church, on a spur above a nearby watercourse. Odo von Bayeux had earthworks erected in order to enclose two castle courtyards, each about 3.4 hectares in size, and to create a mound between the two. The western courtyard was about 170 meters by 240 meters and was enclosed by a 5-meter-high earth wall and a 15-meter-wide moat . The upper edge of the earthworks formed a circular wall about 2.5 meters wide . The western courtyard had an entrance on the western side and one in the northeast corner. The eastern courtyard stretched down the hill to the watercourse and there were probably two fish ponds in it. Another fish pond from the castle further along the watercourse to the southeast called "The Fishers" was probably also connected to the castle. Around this time an L-shaped stone knight's hall was built near the mound in the western courtyard.

The castle complex was unusual for this region and this time; Usually the fortresses of the Normans were smaller ring works. This highlights both the strategic importance of the site and the power of its builder. In size and layout, Deddington Castle was similar to the initial version of Rochester Castle , another large fortress that Odo of Bayeux had built.

Odo von Bayeux rebelled against King Wilhelm II in 1088 without success and then lost all of his lands. His manors in Oxfordshire reverted to the Crown, were split up and fiefs were given to sub-tenants, although it is unclear who initially got Deddington Castle. Possibly it was controlled by the powerful Anglo-Norman Baron Robert de Beaumont , the Earl of Leicester in 1130.

1100-1215

At the beginning of the 12th century, more earthworks were heaped up in order to divide the western courtyard into a bailey about 3 hectares in size and a core castle at the eastern end of about 0.4 hectares. The earthworks were piled up against the knight's hall and partially buried its western wall. It is not known exactly why the new earthworks were built, but it may have served to strengthen the fortifications either against a feared attack by Robert II, Duke of Normandy in 1101 or because of the sinking of the White Ship and the subsequent dynastic crisis of 1120.

Around 1157 the castle belonged to William de Chesney, an Anglo-Norman nobleman who supported King Stephen in the region during the anarchy and then King Henry II after the peace in 1154 . De Chesney had a large part of the castle rebuilt, with a 2-meter-thick curtain wall made of a mortar iron sand quarry around the main castle. The wall ran through the mound, the middle section of which was removed to make room for the curtain wall.

De Chesney also had the interior of the inner castle remodeled, a work program that his descendants continued over the decades that followed. The work included the construction of a chapel, a knight's hall and a solar (dining room for the family), as well as various buildings for the servants. A tower open at the rear with a rectangular floor plan was inserted into the curtain wall at the top of the mound; this tower had to be rebuilt later, probably because of the pressure of the earthworks of the mound. The summit of the mound was re-paved with stone slabs to create paths around the summit. A stone gatehouse was built on the west side of the wall and formed the entrance from the outer bailey.

De Chesney died between 1172 and 1176 and the crown then lent the castle to Ralph Murdoc , De Chesney's nephew and preferred retinue of King Henry II. Murdoc was unpopular with King Henry's successor, Richard I , and Murdoc's relative, Guy de, was so moved Dive and Matilda de Chesney , the opportunity to sue him in the Royal Court of Justice and claim a third of his lands each. The lands around the castle were awarded to Guy de Dive, renamed "Castle Manor" and remained in his family until the mid-14th century. But when Johann Ohneland ascended the English throne, he seems to have confiscated Deddington. The manor was only to have been returned to Guy de Dive in 1204, with Deddington Castle even being exempted from this agreement and coming back under royal control until the following year. After De Dive's death in 1214, Johann Ohneland took the castle back under royal control, where it remained until the king's death the following year.

1215 to the 18th century

Both the village of Deddington and Deddington Castle fell into disrepair in the 13th century. Though the village had grown into a borough with new, planned roads stretching west away from Deddington Castle, the newer, nearby center of Banbury had outstripped it economically. The castles in the Thames Valley , which lacked strong defensive structures, were largely abandoned during this period and Deddington Castle was no exception. Around 1277 contemporaries described the castle as an "old, destroyed castle". In 1281 Robert of Aston and a group of men were able to break open the gates to the castle and enter. The castle was considered "weak" in a report from 1310 and after that no more repairs were carried out on the property.

In 1312 the royal favorite Piers Gaveston may have usurped Deddington Castle. Gaveston was a close friend of King Edward II , but had many enemies among the larger barons; he surrendered to them on the promise that he would be unharmed. He was taken south by Aymer de Valence , the Earl of Pembroke , and imprisoned in Deddington on June 9th when he was riding to visit his wife. It is often heard that Gaveston was imprisoned at Deddington Castle, but he could also have been in the local rectory. Guy de Beauchamp , the Earl of Warwick , disliked Gaveston particularly badly, and the next morning he seized the opportunity to arrest him and bring him back to Warwick Castle , where Gaveston was eventually tried and executed by his enemies.

In the 14th century, the castle was still inhabited, but in a way that archaeologist Richard Ivens compares to a squat : the upper floors of the tower had been abandoned and wood was burned in wild campfires along the inside of the walls. In 1364 Dean and Canons of Windsor bought the castle, the park and the former fish ponds from Thomas de Dive ; the new owner leased the agricultural land, but reserved the right of lower jurisdiction and the profits from it. The tower was demolished during this time, possibly in connection with the sale of bricks from the curtain wall to Canons of Bicester in 1377 . On his visit in the 16th century, the historian John Leland stated only: "There was once a castle in Deddington."

The village of Deddington was heavily involved in the English Civil War from 1641 to 1645 because of its location on the main road from Oxford to Banbury . Historian James Mackenzie noted in the 19th century that the castle was used as a temporary fortress by both royalist and parliamentary troops in this conflict and that in 1644 a royalist garrison was besieged by the parliamentarians there. In the 17th and 18th centuries the castle grounds were used as pasture and for felling wood.

19th to 21st century

In the 19th century, the castle served the local gentry as a relaxation club. B. through cricket and archery . A small lodge was built at the entrance to house a trainer , as was a “pavilion”, a mixture of ballroom and café, on the castle grounds. In 1886 the estate passed from Dean and Canons of Windsor to the Ecclestical Commissioners of the Church of England . The pavilion was demolished at the beginning of the 20th century. Furthermore, building blocks were removed from the remains of the castle and used for local building projects until the 1940s.

The castle grounds were then sold to the Deddington Town Council. The local government wanted to have tennis courts built in the inner castle in 1947, but when work began, the builders dug out medieval clay pots and roof tiles from the castle. Construction ceased and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford funded an archaeological study by Edward Jope and Richard Threlfall that continued until 1953. The plans to build tennis courts were easy to drop because the finds were much more interesting, and the castle grounds were instead turned into a public park. Another phase of archaeological research ran from 1977 to 1979, was funded by Queen's University Belfast and directed by Richard Ivens .

Today, in the 21st century, only the earthworks of the castle remain. The western courtyard is administered by the local government and the inner castle by English Heritage , while the eastern courtyard is still used for agriculture. The entire area is considered a Scheduled Monument .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire. A Summary of Excavations 1977-1979 in South Midlands Archeology . CBA Group 9 newsletter. No. 13 (1983). P. 35.

- ^ A b Norman John Greville Pounds: The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3 . P. 61.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Parishes: Deddington, A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 11: Wootton Hundred (Northern Part) (1983) , pp. 81-120 . Victoria County History. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honor of Bayeux in Oxoniensis . No. 49 (1984). P. 101.

- ^ Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honor of Bayeux in Oxoniensis . No. 49 (1984). P. 108.

- ^ A b c Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honor of Bayeux in Oxoniensis . No. 49 (1984). Pp. 113-114.

- ↑ Oliver Hamilton Creighton: Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England . Equinox, London 2005. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8 . P. 37.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j List Entry Summary: Deddington Castle . English Heritage. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honor of Bayeux in Oxoniensis . No. 49 (1984). Pp. 111, 113.

- ^ A b c d e f g Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honor of Bayeux in Oxoniensis . No. 49 (1984). P. 111.

- ^ Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honor of Bayeux in Oxoniensis . No. 49 (1984). P. 114.

- ^ Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honor of Bayeux in Oxoniensis . No. 49 (1984). Pp. 114-115.

- ^ Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honor of Bayeux in Oxoniensis . No. 49 (1984). Pp. 112-115.

- ^ A b Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honor of Bayeux in Oxoniensis . No. 49 (1984). P. 112.

- ^ A b Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire. A Summary of Excavations 1977-1979 in South Midlands Archeology . CBA Group 9 newsletter. No. 13 (1983). P. 37.

- ^ Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire. A Summary of Excavations 1977-1979 in South Midlands Archeology . CBA Group 9 newsletter. No. 13 (1983). Pp. 37-39.

- ^ A b Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honor of Bayeux in Oxoniensis . No. 49 (1984). P. 115.

- ^ A b c d e Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honor of Bayeux in Oxoniensis . No. 49 (1984). P. 117.

- ^ A b Anthony Emery: Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300-1500 . Volume 3: Southern England . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-58132-5 . P. 15.

- ^ A b Adrian Pettifer: English Castles: A Guide by Counties . Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2002. ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5 . P. 204.

- ^ Michael Prestwich: The Three Edwards: War and State in England, 1272-1377 . 2nd Edition. Routledge, London 2003. ISBN 978-0-415-30309-5 . Pp. 74-75.

- ^ Michael Prestwich: The Three Edwards: War and State in England, 1272-1377 . 2nd Edition. Routledge, London 2003. ISBN 978-0-415-30309-5 . Pp. 75-76.

- ^ A b Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire. A Summary of Excavations 1977-1979 in South Midlands Archeology . CBA Group 9 newsletter. No. 13 (1983). P. 39.

- ^ Richard J. Ivens: Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English Honor of Bayeux in Oxoniensis . No. 49 (1984). P. 118.

- ↑ James D. Mackenzie: The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure . Volume 2. Macmillan, New York 1896. p. 155.

- ^ A b c Edward M. Jope, Richard I. Threlfall: Medieval Finds in the Oxford District in Oxoniensis . Nos. 11-12 (1946-1947). P. 167.

Web links

Coordinates: 51 ° 58 ′ 52.7 " N , 1 ° 18 ′ 53.6" W.