German listeners!

German listeners! is the title of a series of 55 radio speeches by Thomas Mann , which the German program of the BBC aired regularly once a month between October 1940 and May 1945. In addition, there were individual special broadcasts and a final address on the New Year of 1946.

It was five to eight-minute, compelling statements speeches in which the author of the political situation in Germany in the period of National Socialism dealt, the war events commented and pointed words of warning to his countrymen. A first collection with 25 broadcasts was published in 1942, a second included 55 texts.

content

After Thomas Mann had issued a warning against National Socialism in various publications , for example in his appeal to reason of 1930, he continued this form of warning with the speeches.

His speeches are based on the difference between Germans (or their culture) and National Socialism, a basic conviction that determined his political thinking during his exile. They tend to aim to make German listeners aware of this difference and thereby induce them to resist Adolf Hitler .

Thomas Mann's speeches aimed at political education work were intended to counteract the “blocking off Germany from the world and its feelings and thoughts” by trying to make people aware of the falsification and corruption of concepts and ideas such as revolution and socialism , freedom and love of the country carried out by National Socialist propaganda .

While some of the speeches dealt with current events - an order from Hitler for the day, a speech by Roosevelt , the occupation of Greece - others dealt with fundamental moral questions in connection with Nazi crimes on the one hand and the reactions of the Allies on the other. He addressed the destruction of Lidice , the bombing of the city center of Rotterdam , which heralded “moral insanity” , the air strikes on Coventry and the conditions in the Warsaw ghetto, as well as the escalation stages of the Holocaust . He put the attacks of the Royal Air Force on German cities like Hamburg, Cologne and Essen in a context of guilt and pointed out that they were retaliatory measures. The delusion and belief of the German people in “their prerogative to act of violence” would take revenge. The suffering of the German victims does not arise from the cruelty of the Allies, but from the culpable involvement in National Socialism.

In January 1942 he went into details of the persecution of the Jews : "The Nazis consciously make history with all their deeds, and the trial gassing of the four hundred young Jews [...] is an expression of the spirit and sentiments of the National Socialist revolution ..." After he had read an article in the American magazine Life in February 1942 with details about “German atrocities in Poland”, in another address he denounced the “killing of no less than eleven thousand Polish Jews with poison gas” that were put in “airtight vehicles and turned into corpses within a quarter of an hour ”. You have "the description of the whole process, the screams and prayers of the victims and the good-natured laughter of the SS Hottentots who carried out the fun."

background

Thomas Mann moved to the United States in 1938 and later settled in California . The United States was the most important country of emigration for many Germans who had escaped persecution, found no security in other European countries and found themselves here in numerous exile organizations, from which Thomas Mann usually stayed away. Despite this distance, he developed a lively political activity directed against National Socialism. This was reflected above all in the radio speeches, which were based on his belief "in the coming victory of democracy", the title of a lecture that the author had given in fifteen American cities in 1938.

As Thomas Mann explained in the foreword to the first edition, the BBC asked him in the autumn of 1940 to send "short speeches" to his "compatriots" at regular intervals via its broadcaster in order to be able to influence them in line with his frequently expressed convictions. He did not want to miss this opportunity, especially since it was now possible to broadcast from London over long waves, so that his words could be heard using the “only recipient type”, the people's receiver , which according to the regulation is extraordinary Broadcasting operations when listening to enemy broadcasts was prohibited.

While he initially sent the texts to London , where they were read out by a “German-speaking employee of the BBC”, at his suggestion they later used a “more complicated, yet more direct and therefore more sympathetic method”: From March 18, 1941, he spoke in the “ Recording Department of the NBC “in Los Angeles, the texts themselves on a record, which was first sent to New York and from there telephoned to London. So those “who dared to listen over there” could hear his own voice.

Apparently, according to Thomas Mann, there are also people in the occupied territories “whose hunger and thirst for the free speech is so great” that they have defied the associated dangers. Hitler himself gave the "exhilarating and disgusting proof" of this by insulting the author in a beer cellar speech in Munich as someone who was trying to incite the German people against him and his system. The absurdity of Hitler's words consists in the fact that “the Führer” on the one hand expressed his “contempt for the German people” and his conviction of their cowardice, submissiveness and stupidity of “allowing themselves to be deceived”, but forgetting how it was possible to see in him at the same time a “master race destined for world domination”.

Effect and reception

It is uncertain what effect the speeches had and to what extent the German resistance was encouraged by them. Since no other German author in exile is known to have carried out such a large-scale campaign, the attempt at influence should not be underestimated. The fanatization of many Germans by Joseph Goebbels ' propaganda speeches and the apparent identification with National Socialism sometimes seemed to give the lie to Thomas Mann's belief in the resistance of German culture; Traces of resignation can sometimes be found in some of his speeches.

Some commentaries deal with Mann's assessments of the Allied bombing attacks as a reaction to the war sparked by Nazi Germany in general and individual acts of war, military strategies of the Wehrmacht and war crimes in particular. On the occasion of the anniversary of the destruction of Coventry , Mann had once again raised the question of whether Germany had thought “it would never have to pay for the crimes which its lead in barbarism would allow it.” The attacks on German cities were part of this expected reaction . Even when it came to Lübeck , his hometown, where St. Mary's Church could have been damaged, he thought of Coventry - "and ... nothing against the doctrine that everything must be paid for." His sense of justice is based on " a special test ”if“ the so-called Buddenbrook House in Mengstrasse ”was actually destroyed. These ruins would not frighten those "who live not only from sympathy for the past, but from that for the future". Hitler's Germany has neither tradition nor future. In addition to people from Lübeck, there will also be people from Hamburg, Cologne and Düsseldorf who “wish the Royal Air Force good luck” when they hear the roar of the machines above them.

In view of these considerations, Klaus Harpprecht stated that it did not seem to have occurred to Thomas Mann that the people who were frightened by the bombings in the basements, even if they had longed for the downfall of the regime, would have nothing but fear for themselves and their families and Mann's language at that moment was that of the zeitgeist , who believed it recognized the deadly enemy.

By Ernst Junger , who during the presentation of the German speech under the SA , was ists, however, not directly involved in the disturbances, there are no significant and longer statements to Thomas Mann. It was only relatively late that he made some comments on the radio speeches and assessed them negatively. As he said in a Spiegel conversation ("A brotherhood drinking with death") on August 16, 1982, he was always annoyed when he heard during a BBC broadcast that "a German city had gone up in flames" and Thomas Man held "his speeches" to it. On the other hand, he admired him as a great stylist "who showed responsibility for the German language".

Thomas Mann's statements, which in retrospect are irritating in view of the victims of the air war , and his exaggerated belief that those affected in the bombed cities such as Hamburg , Düsseldorf , Cologne and Essen would internally support the attacking pilots, are not an isolated case in Thomas Mann's late work. They can be seen as an echo of an expectation that was widespread among exiles in the 1930s that there might be resistance to the regime, which the Allies expressly stated as one of the reasons for the bombing.

expenditure

- German listeners! A selection from the radio messages to the German people. Ed. And publisher: Freier Deutscher Kulturbund in Great Britain, undated (1944)

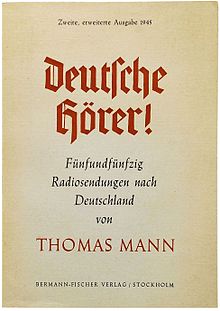

- German listeners! 55 radio broadcasts to Germany. Bermann Fischer , Stockholm 1945

- German listeners! 25 radio broadcasts to Germany. Bermann-Fischer, Stockholm 1942

- German listeners! Radio broadcasts to Germany. With: European listeners! Series: Science and Philosophy, 10th ed. Europ. Cultural society. Verlag Darmstädter Blätter, Darmstadt 1986 ISBN 3-87139-089-5

-

German listeners! Radio broadcasts to Germany from 1940 - 1945. Fischer TB 5003, Frankfurt 1987

- ibid., in: Collected works in 13 volumes. Volume 11: Speeches and essays, 3rd - 2nd, through. Ed. S. Fischer, Frankfurt 1974, 1990 ISBN 3-10-048177-1 , pp. 930-1050

literature

- Sonja Valentin: "Stones in Hitler's Window" Thomas Mann's radio broadcasts German listeners! 1940-1945. Wallstein, Göttingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8353-1696-6 .

- Tobias Temming: "Brother Hitler"? On the importance of the political Thomas Mann. Essays and speeches from exile. WVB Wissenschafts-Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86573-377-1 .

- Stefan Bodo Würffel : Visions of doom, death rhetoric and disaster music in the late Thomas Mann. In: Thomas Sprecher (Ed.): Magic of life and death music. On Thomas Mann's late work. The Davos Literature Days 2002. Thomas Mann Studies. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-465-03294-2 , pp. 183-201.

Individual evidence

- ^ Theo Stammen: Thomas Mann and the political world , in: Thomas-Mann-Handbuch, Fischer, Frankfurt 2005, p. 45.

- ↑ German listeners! 55 radio broadcasts to Germany. In: Kindlers New Literature Lexicon. Kindler, Munich 1990, p. 64.

- ^ Stefan Bodo Würffel : Doom visions, death rhetoric and disaster music in the late Thomas Mann. In: Magic of life and death music. The Davos Literature Days 2002. Thomas Mann Studies. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2004, p. 186

- ↑ Quotation from: Stefan Bodo Würffel: Doom visions, death rhetoric and music for catastrophes in the late Thomas Mann. In: Magic of life and death music. The Davos Literature Days 2002. Thomas Mann Studies. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2004, p. 186

- ↑ Quoted from: Christian Hülshörster: Thomas Mann and Oskar Goldberg's "Reality of the Hebrews" . Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1999, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Quoted from: Christian Hülshörster: Thomas Mann and Oskar Goldberg's "Reality of the Hebrews" . Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 123

- ^ Theo Stammen: Thomas Mann and the political world , in: Thomas-Mann-Handbuch, Fischer, Frankfurt 2005, p. 44.

- ↑ Thomas Mann: German listeners, fifty-five radio broadcasts to Germany. In: Thomas Mann: Collected works in thirteen volumes , Volume 11, speeches and essays, Fischer, Frankfurt 1974, p. 983.

- ↑ Listening to stations from neutral or allied states was also forbidden, but was punished less depending on the news broadcast; see Ordinance on Extraordinary Broadcasting Measures

- ↑ Thomas Mann: German listeners, fifty-five radio broadcasts to Germany. In: Thomas Mann: Collected works in thirteen volumes , Volume 11, speeches and essays, Fischer, Frankfurt 1974, p. 985.

- ↑ Information from: Thomas Mann, Thomas Mann speaks to the German people , Essays, Volume 5, Germany and the Germans, Commentary, Fischer, Frankfurt, 1996 p. 354

- ^ Theo Stammen: Thomas Mann and the political world , in: Thomas-Mann-Handbuch , Fischer, Frankfurt 2005, p. 45.

- ↑ Thomas Mann: Deutsche Hörer , special broadcast, April 1942, in: Fifty-five radio broadcasts to Germany , collected works in thirteen volumes, volume 11, speeches and essays, Fischer, Frankfurt 1974, p. 1034.

- ↑ Thomas Mann: Deutsche Hörer , special broadcast, April 1942, in: Fifty-five radio broadcasts to Germany, collected works in thirteen volumes, volume 11, speeches and essays, Fischer, Frankfurt 1974, p. 1035.

- ↑ Quotation from: Stefan Bodo Würffel: Doom visions, death rhetoric and music for catastrophes in the late Thomas Mann. In: Magic of life and death music. The Davos Literature Days 2002. Thomas Mann Studies. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2004, p. 185

- ↑ Klaus Harpprecht : Thomas Mann, Eine Biographie , Rowohlt, Reinbek 1995, p. 1280

- ^ So Hermann Kurzke : Republican Politics In: Thomas Mann. Life as a work of art. Beck, Munich 2006, p. 365

- ↑ Quoted from: Hermann Kurzke: Republican Politics In: Thomas Mann. Life as a work of art. Beck, Munich 2006, p. 366

- ^ Stefan Bodo Würffel: Doom visions, death rhetoric and disaster music in the late Thomas Mann. In: Magic of life and death music. The Davos Literature Days 2002. Thomas Mann Studies. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2004, p. 186

- ↑ 131 p. There are translations into English, French, Brazilian Portuguese, Argentine, Catalan & Mexican Spanish - also: Insel-Bücherei No. 900, Insel Verlag , Leipzig 1970, 1971 (1975: 2nd edition)

- ^ Also Deutscher Bücherbund, Stuttgart; Ex Libris, Zurich; also as Fischer TB ISBN 3-596-10321-5