Uruk

Uruk on the map of Iraq |

Uruk ( Sumerian Unug ; Biblical Erech ; Greco-Roman Orchoe, Orchoi ), today's Warka , is located about 20 km east of the Euphrates near the ancient city of Ur . In ancient times , the Mesopotamian city lay directly on the river. Uruk was formerly nicknamed the sheepfold . The city is one of the most important sites in Mesopotamia and is named for the Uruk period (approx. 3500–2800 BC).

Uruk is where the first writing was found. It was already at the end of the 4th millennium BC. BC one of the leading political centers of the Sumerian early period. Uruk experienced a second great flowering phase in the Hellenistic period in the last centuries BC. The main gods are the goddess of love and war Inanna / Ishtar and the sky god An , whose temples shaped the cityscape.

The archaeological sites of Uruk, along with those of Ur and Eridu and marshland areas in southern Iraq, are UNESCO World Heritage sites .

Excavations

The English geologist William Kennett Loftus carried out the first investigations in Uruk-Warka in the years 1849-1850 and 1854. In 1912/13 the excavations of the German Orient Society began under Julius Jordan and Conrad Preusser. The work was resumed after the First World War in 1928 and continued until 1939. In 1954 and in the following years several systematic excavations were carried out under the direction of Heinrich Lenzen . These excavations brought various ancient Sumerian documents and a large number of legal and educational tables from the Seleucid period to light. They were published by Adam Falkenstein and other German epigraphers , some of them in the Uruk-Warka Collection in Heidelberg .

The last German excavation campaign before the Iraq war was carried out in the summer of 2002 under the direction of Margarete van Ess from the DAI . The evaluation of satellite images in 2005 refuted reports of robbery excavations in Uruk.

The city and its history

The ruin of Uruk (Warka) is the largest city ruin in southern Babylonia with an area of 550 hectares. The ancient city of Uruk was inhabited for a period of about 5000 years, from the early Obed period (5th millennium BC) to the 3rd century AD. The center of the city is from the two cult centers of the both of the city's main gods. The Kullaba district with the Anu Temple and its temple tower ( ziggurat ) is the main place of worship of the sky god An, while the Eanna district is the main shrine of the goddess Inanna / Ishtar .

Uruk time

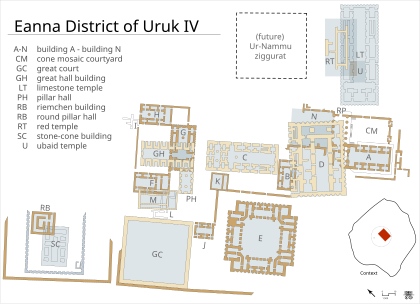

Already from approx. 3500 BC. Uruk was a large urban center. Around 3400 BC The settlement hill was already 19 m high. It can arguably be called one or even the center of the emergence of Sumerian culture. This period is called the "Late Uruk Period " in archeology and extends to around 3000 BC. The center of the city was the sanctuary of Inanna, called Eanna . This reached monumental proportions as early as the fourth millennium BC. The most important part was the so-called 'limestone temple' (in the illustration of the floor plan on the top right, "Limestone Temple", abbreviated LT), which was an approx. 70 × 30 m building made of limestone blocks . However, it is not certain whether these limestones only formed the foundations of an adobe building or whether the entire height of the building was built in limestone. The facade of the temple was designed with a niche structure. Inside is a T-shaped courtyard or hall. In addition to this main temple, there were other facilities, including the so-called stone pen temple, a building whose walls are decorated with geometric mosaics. Wooden beams twelve meters long, remains of large sculptures and reliefs, animal figures, intricately designed stone vessels and cylinder seals were also found. The temple complex was rebuilt and expanded several times and received a ziggurat in the time of the third dynasty of Ur , which was built by Urnammu .

The ziggurat of the god An was also built here (called the 'White Temple'); it is the other major temple complex in Uruk.

Around 3000 BC The entire settlement mound was leveled and new buildings were erected. At the height of its development, the city reached an area of 5.5 km², the size of similarly dimensioned city facilities that were archaeologically developed in regions of the Indus culture , for example Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro . These centers were probably the largest cities in the Old World at that time . Uruk only became known around 600 BC. Exceeded in size by Babylon .

Before the conquests of the Sargon of Akkad , Uruk was the hegemonic power in Sumer.

In rain-poor Mesopotamia, water for agriculture was channeled to the fields through canals and dams. There was always the danger that the facilities would be destroyed by enemies.

Historians believe that around 3000 BC in Uruk A catastrophe occurred due to a dam breach. The scriptures suddenly end at this time. The dam was probably destroyed on purpose or as a result of fighting between Sumerians and Semites . It has been suggested that this event was reflected in the Mesopotamian flood reports.

Sumerian Period: Early Dynastic Period

Even in the early Dynastic period , Uruk was one of the most important cities in a system of competing city-states. In the Early Dynastic Period I (FD I) the city was surrounded by a large city wall that was about nine kilometers long. The city wall has so far only been examined selectively. The Gilgamesh epic reports that the wall was built by Gilgamesh, the legendary king of Uruk, himself.

Neo-Babylonian, Seleucid and Parthian times

Uruk's extensive and preserved temple archives from the Neo-Babylonian period document its social importance as a distribution center. In times of hunger, families could dedicate their children to the temple as lay brothers / sisters.

Uruk was also an important city in the Hellenistic period. The most important temples in the city have been maintained and renovated. There were also new temples , such as the Anu and Antum temples, part of the Bit Resch cult site and a temple building called Irigal . The former are extremely large and monumental systems. The ziggurat in the Eanna temple district was also renovated during this time.

From Parthian period produced some temple new buildings, such as the so-called. Gareus - Temple , whereas the investments Sumerian deities fell slowly or were not rebuilt after fires. Parts of Parthian residential areas have been excavated, some of which have unearthed houses with rich furnishings ( stucco decorations). Numerous burials were found under the residential buildings, often dug in their courtyards, some in glazed clay coffins. The city still existed in Sassanid times.

Nearby is also the Nufedschi facility , the importance of which is still puzzling research.

Kings of Uruk

According to the Sumerian king lists, Uruk was founded by Enmerkar , who brought the official title of king from the city of Eanna . His father Mesch-ki-ag-gascher "disappeared at sea". Other historical kings of Uruk are Lugalzagesi (who conquered Uruk) and Utuḫengal . The semi-mythical Gilgamesh was according to the Sumerian king lists from about 2652 BC. BC to 2602 BC Here king. He completed Uruk's independence and walled the city. Gilgamesh was also said to have commissioned the Eanna Temple. Uruk later played an important role in the battles of Babylon against the kingdom of Elam around 1200 BC. BC, which suffered serious losses.

See also

Exhibitions

- 2013 Uruk. 5000 years of the megacity , Pergamon Museum , Berlin, then 2013/2014 in Herne, LWL Museum for Archeology , catalog.

literature

- RM Boehmer, Uruk-Warka: In: Eric M. Meyers (Ed.): The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archeology in the Near East. Volume 5, Oxford University Press (et al.), Oxford 1997, ISBN 0-19-506512-3 , pp. 294-298

- Burchard Brentjes : Peoples on the Euphrates and Tigris. Koehler and Amelang, Leipzig / Vienna 1981. ISBN 3-7031-0526-7 .

- Nicola Crüsemann et al .: Uruk. 5000 years of the megacity . Reiss-Engelhorn-Museum, Mannheim with Imhof-Verlag, Petersberg 2013, ISBN 978-3-86568-844-6 .

- Margarete van Ess : 1912/13: Uruk (Warka). The city of Gilgamesh and Ishtar. In: G. Wilhelm (Ed.): Between the Tigris and the Nile. 100 years of excavations by the German Orient Society in the Middle East and Egypt. Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 32-41.

- Margarete van Ess: The excavations in Uruk-Warka. In: German Archaeological Institute, Orient Department - Baghdad Branch, 50 Years of Research in Iraq 1955-2005 , Berlin 2005, pp. 31–39.

- Margarete van Ess and Elisabeth Weber-Nöldeke (eds.): Letters from Uruk-Warka: 1931–1939 / Arnold Nöldeke , Reichert, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-89500-485-8

- Julius Jordan: Uruk-Warka. After the excavations of the German Orient Society. WVDO 51. Biblio, Bissendorf Kr. Osnabrück 2006. ISBN 3-7648-2645-2

- Gunvor Lindström: Uruk. Seal impressions on Hellenistic clay bulls and clay tablets. von Zabern, Mainz 2003. ISBN 3-8053-1902-9

- Adolf Leo Oppenheim : Ancient Mesopotamia - portrait of a dead civilization. Rev. ed by Erica Reiner . University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1977. ISBN 0-226-63186-9

- Michael Roaf : World Atlas of Ancient Cultures. Mesopotamia. Munich 1990, pp. 59-61.

- G. Rouvé: Overview of Damage Cases on Dams. In: Communications from the Institute for Hydraulic Engineering and Water Management. Aachen 9th 1977.18. ISSN 0343-1045

Web links

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- Uruk - 5000 years of megacity. Exhibition in the Pergamon Museum Berlin from April 25 to September 8, 2013.

Individual evidence

- ↑ For the type of landscape, see the settlement area of the Marsh Arabs around the Shatt al-Arab .

- ↑ Iraq World Heritage List (Eng.)

- ↑ Margarete van Ess, H. Becker, J. Fassbinder, R. Kiefl, I. Lingenfelder, G. Schreier, A. Zevenbergen: Detection of Looting Activities at Archaeological Sites in Iraq using Ikonos Imagery , In: J. Strobl, Th. Blaschke, G. Griesebner: Applied Geo-Informatik 2006. Contributions to the 18th AGIT Symposium Salzburg 2006 (2006) pp. 669–678, here quoted from the short report Kulturerhalt des Irak by the DAI, http://www.dainst.org/ de / project / kulturerhalt-des-irak? ft = all ( Memento from June 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Adolf Leo Oppenheim: “ In Uruk, in South Mesopotamia, the Sumerian civilization reached its creative climax. This can be seen from the references to this city in religious and especially in literary texts, also with a mythological background; the historical tradition as it was handed down in the Sumerian king lists confirms this. From Uruk the political focus evidently shifted to Ur. "( Lit .: Oppenheim)

- ^ Uruk (Warka): Structure of an ancient oriental city. Urban research in the metropolis of the legendary King Gilgamesh (5th millennium BC – 4th century AD) , http://www.dainst.org/de/project/uruk?ft=all ( Memento from August 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

Coordinates: 31 ° 19 ′ 20 ″ N , 45 ° 38 ′ 10 ″ E