Battle of Mukden

| date | February 20 to March 10, 1905 |

|---|---|

| place | South of Mukden , Manchuria |

| output | Decisive Japanese victory |

| consequences | Japan occupies southern Manchuria, Russia withdraws into northern Manchuria |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| Troop strength | |

| 343,000 soldiers and 800 cannons |

281,000 soldiers 500 cannons |

| losses | |

|

88,352 total losses

|

75,504 total losses

|

Port Arthur (Sea Battle) - Chemulpo - Yalu - Nanshan - Te-li-ssu - Hitachi-Maru Incident - Motien Pass - Tashihchiao - Hsimucheng - Port Arthur (Siege) - Yellow Sea - Ulsan - Korsakov - Liaoyang - Shaho - Sandepu - Mukden - Tsushima - Sakhalin

The battle of Mukden ( Japanese 奉天 会 戦 , Hōten kaisen ) was from February 7th jul. / February 20th greg. until February 25th jul. / March 10, 1905 greg. between the Imperial Japanese Army and the Imperial Russian Army near the Manchurian city of Mukden . It was one of the greatest land battles that occurred before World War I and was the decisive land battle in the Russo-Japanese War . The city of Mukden is now called Shenyang and is the capital of Liaoning Province in China.

The Russian armed forces, 340,000 men under the command of General Alexei Nikolajewitsch Kuropatkin , defended their positions against the 280,000 men of the Imperial Japanese Army under the command of Field Marshal ( Gensui ) Ōyama Iwao . With over 600,000 participating soldiers, it was the largest battle since the Battle of Leipzig in 1813 until the beginning of the First World War .

prehistory

After the Battle of Liaoyang (August 24 to September 4, 1904), the Russian forces withdrew across the Shaho River south of Mukden to regroup. They then counterattacked and attacked the Japanese from October 5 to October 17 at the Battle of Shaho. The counterattack failed, but delayed the advance of the Japanese troops.

A second Russian counterattack at the Battle of Sandepu (January 25-29 , 1905) was just as unsuccessful.

The capture of Port Arthur by General Nogi released the Japanese 3rd Army , which headed north to reinforce the Japanese front in front of Mukden for an attack.

By February 1905, the Japanese reserves had suffered badly. With the arrival of the 3rd Army, the entire Japanese combat force was now concentrated in front of Mukden for an attack. Heavy losses, severe winter cold and the approaching arrival of the Russian 2nd Pacific Squadron put Field Marshal Oyama under pressure. This sought the complete annihilation of the Russian troops and did not just want to achieve a victory after which the Russians could withdraw deeper into Manchuria.

List of forces

Russian lineup

The Russian front in front of Mukden stretched over a length of 140 km, with shallow depth and a central reserve. On the right flank was the 2nd Manchurian Army under General Baron von Kaulbars , who replaced the unfortunate General Oskar Grippenberg . In the middle, holding the railway line and highway, stood the 3rd Manchurian Army under General Bilderling . The hilly terrain on the eastern flank was held by the 1st Manchurian Army under General Nikolai Linewitsch . This flank contained two thirds of the Russian cavalry under General Paul von Rennenkampf . General Kuropatkin had set up his entire armed forces defensively in positions that made it difficult or even impossible to take offensive action when the opportunity arises without tearing large gaps in his own front.

Japanese lineup

The Japanese concentrated the 1st Army under General Kuroki and the 4th Army under General Nozu moved east towards the railway line. The 2nd Army (General Oku ) was deployed in the west. General Nogi's 3rd Army was approaching hidden behind the 2nd Army. A newly formed 5th Army under General Kawamura was used as a diversion on the eastern Russian flank.

Considerations of the commanders

General Kuropatkin was convinced that the main Japanese attack would come from the mountainous terrain in the east - the Japanese had shown themselves to be very effective in previous battles in the mountainous terrain. The presence in this sector of Japanese 5th Army troops, who were veterans, confirmed his view.

Field Marshal Oyama's plan was to set up his armies in a kind of crescent moon to enclose Mukden and prevent the Russian troops from fleeing. He gave precise instructions not to get involved in street fighting in Mukden under any circumstances. Above all, this was intended to avoid losses in the civilian population, as the Japanese did not want to turn the Chinese population against them - a great contrast to the First Sino-Japanese War and the Second Sino-Japanese War .

The battle

The battle began with the attack of the Japanese 5th Army , which attacked the Russian left flank on February 20th. On February 27, 1905, the Japanese 4th Army attacked the Russian right flank. Shortly afterwards, the entire front was attacked. On the same day the Japanese 3rd Army began their encircling march, in which they circled Mukden in a wide arc.

By March 1, 1905, activities on both sides on the eastern and central fronts had stalled. The Japanese had made minor gains in terrain, but won them with great losses. General Kuropatkin had his troops retreat on the eastern flank from March 7th in order to counter the encircling march of the Japanese 3rd Army around the western flank. He was so concerned about this containment movement that he personally commanded the counterattack. The movement of troops from east to west was poorly coordinated by the Russians and disordered their 1st and 3rd Manchurian armies . As a result, Kuropatkin decided to move his entire armed forces north towards Mukden. He wanted to fight the Japanese on the southern city limits and on the banks of the Hun River .

Field Marshal Oyama recognized the chance he had been waiting for and had his previous order “attack” changed to “pursue and destroy”. Luck was with the Japanese because the hun was still frozen. Although guarded by the left flank of the Russians under Major General Mikhail Aleksejew , the river was not an obstacle to the advancing Japanese troops. While crossing the river, the Japanese nevertheless encountered heavy Russian artillery fire and bitter resistance from the Russians, who were meanwhile commanded by General Paul von Rennenkampff . Despite heavy losses, the Japanese were able to maintain the northern side of the river after a tough battle. The Russian defense collapsed on this section and split off the Russian left flank from the main army. At the same time, the Japanese formed a promontory 15 km west of Mukden, which allowed them to enclose the Russians on their right flank.

On the point of being trapped, with no hope of victory, General Kuropatkin gave the order for a general retreat at 6:45 p.m. on March 9th. The Russian retreat was severely hampered by General Nozu's break-in over the Hun, and the orderly retreat quickly turned into a desperate escape. The panicked Russians left their wounded, weapons and supplies behind on their flight towards Tieling .

At 10:00 a.m. on March 10th, Japanese troops entered Mukden. After that they set out again to chase the fleeing Russian troops. General Oyama, however, had to break off the fast pursuit because of overstretched supply lines if he was able to maintain the pursuit of the enemy to some extent. The pursuit was stopped 20 kilometers behind Mukden. However, the Russians had already fled further north towards the Sino-Russian border at high speed.

Field railways

Two military field railways were used near Mukden: One was initially moved from the end of the Fuschung coal railway to Kaolinszy. It reached a length of 62 km. The work was made very difficult by frost and the numerous watercourses that had to be crossed. Since the Rennkampff department , for which the field railway was intended, was not very strong, its capabilities were not fully utilized. Wounded people were promoted more often, once two rifle companies were brought into combat positions. When the Rennkampff department withdrew, the field railway was partially dismantled in enemy fire. The favorable experience with this field railway prompted the construction of a second line, starting from the Fuschung coal line, for the 1st Army, which was 21 km in length and from which 7.5 km of branch lines led to warehouses and hospitals.

On the right wing of the position in front of Mukden, field railways were partly laid over the ice of the rivers. They had a length of 86 km. It took 25 days to build. Most of them were equipped with telephones. Later a 16 km long stretch to Mukden was built in 4 days. Only by using the light railroad was it possible to save the heavy artillery when retreating. The demolition was only partially successful. Due to the defeat at Mukden, about 300 km of flying track were lost. Replacement material for horse and machine trains was not on the way until the peace agreement.

losses

The Russian losses amounted to nearly 90,000 men. They had lost most of their supplies, as well as their artillery and machine guns. Fearing the Japanese would advance further, General Kuropatkin had the city of Tieling set on fire as part of the scorched earth tactic . At the same time, the Russian troops were positioned 10 days' march north in order to create a new defensive position. In danger of being trapped in this new position, the Russians withdrew completely from the region shortly afterwards.

With losses of 75,000 men, the Japanese had significantly more dead and wounded than the Russians in relation to troop strength. However, they had won the day with an outnumbered army. The Japanese captured 58 Russian artillery pieces.

After the Battle of Mukden there was no further fighting as both sides were exhausted from the fighting.

consequences

With the defeat of the Russian Manchurian Army in Mukden, the Russian forces were thrown out of southern Manchuria. The Japanese, for their part, fought with excessive supply lines and could not completely destroy the Russians. Although Kuropatkin's forces were demoralized, short of supplies, and near disintegration, they continued to pose a military threat to the Japanese. But the Battle of Mukden had been decisive enough to shake Russian morale. Furthermore, the Trans-Siberian Railway was in Japanese hands and thus the connection to Vladivostok was interrupted. The war was finally decided by the Japanese victory in the sea battle at Tsushima .

The Japanese victory shocked the great powers of Europe. The Japanese had shown their tactical strength on the battlefield, despite Russian numerical superiority. The battle proved that the Europeans were not unbeatable, but could even be decisively defeated. The two Russian generals Alexander Samsonow and Paul von Rennenkampf, future commanders of armies in the even more disastrous Battle of Tannenberg in World War I, met each other with dislike. Von Rennenkampf, the left flank commander during the battle, was accused by Samsonov of not providing him with adequate support during the fighting.

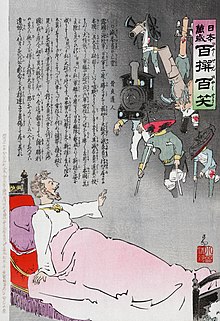

When the news of the defeat reached St. Petersburg, Tsar Nicholas II was shocked. He realized that a relatively small Asian country like Japan could defeat a major European power like Russia. The tsarist government was irritated by the incompetence of its military leaders and again turned its attention to the Balkans.

Cinematic implementation

The battle was themed in 2011 in episode 12 of the Japanese television series Saka no Ue no Kumo .

literature

- Richard Connaughton: Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear . Cassell, 2003, ISBN 0-304-36657-9 .

- Rotem Kowner : Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War . Scarecrow, 2006, ISBN 0-8108-4927-5 .

- Christopher Martin: The Russo-Japanese War . Abelard Schuman, ISBN 0-200-71498-8 .

- Bruce W. Menning: Bayonets before Battle: The Imperial Russian Army, 1861-1914. Indiana University, ISBN 0-253-21380-0 .

- Ian Nish: The Origins of the Russo-Japanese War . Longman, 1985, ISBN 0-582-49114-2 .

- FR Sedwick: The Russo-Japanese War . Macmillan, 1909.

Web links

- Animated map of the Battle of Mukden - English

Individual evidence

- ^ Victor Freiherr von Röll: Encyclopedia of the Railway System. Second edition, Volume 5, Urban & Schwarzenberg, Berlin, 1914, p. 57.

- ^ E. Hartmann: War-technical journal for officers of all weapons. Ninth year, Berlin 1906. Issue 2, p. 89.

- ↑ Njesnamoff: "war experience", "Invalid". 195 ff.