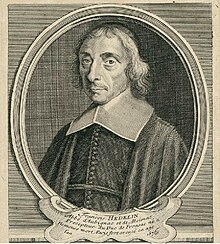

François Hédelin

François Hédelin, abbé d'Aubignac et de Meymac (born August 4, 1604 in Paris , † July 25, 1676 in Nemours , today in the Seine-et-Marne department ) was a French writer , dramaturge , poet and theoretician of the French theater des 17th century.

François Hédelin wrote a theory of the Aristotelian three units , which was important for the French theater of the 17th century, and described this in 1657 in his main work La Pratique du Théâtre .

Life

François Hédelin was the son of Claude Hédelin, a lawyer at the Paris Court of Justice, and Catherine Paré, daughter of the famous Paris surgeon Ambroise Paré . François Hédelin initially followed in his father's footsteps and worked as a lawyer in Nemours for several years. In 1631 he was appointed tutor of the Duke of Fronsac, Jean Armand de Maillé-Brézé , a nephew of Cardinal Richelieu , who made him abbot of Aubignac and Mainac. The death of the Duke of Fronsac in Orbetello in 1646 put an end to his hopes for further promotions and returned to Nemours as Abbot d'Aubignac. From then on he dealt with literature.

Despite all his efforts, he did not manage to get into the Académie Française . This failure and undoubtedly the death of Richelieu, who had greatly appreciated and promoted the work of d'Aubignac, probably delayed the publication of his main work, the Pratique du Théâtre , until 1657. Prior to that, d'Aubignac tried in the period between 1642 and 1650 to write four tragedies: a "tragédie mythologique", a "tragédie nationale", a "tragédie chrétienne" and a "zénobie" (1645), all of which had moderate success .

D'Aubignac drew his circles among others in the "Académie allégorique" and the "Académie des Belles Lettres", in the course of which he directed his criticism, for example, against fashion novels and especially against Pierre Corneille .

In his dissertation ( Conjectures académiques, 1670), which was only published 40 years after his death, he also dealt with the " Homeric question ". In it he denounced the incoherence and the barbaric archaism of Homeric poetry and finally doubted the entire existence of Homer .

La Pratique du Théâtre

D'Aubignac's Pratique du Théâtre is closely related to other theories of drama of the 17th century. What they have in common is the demand for the observance of the three units , the orientation of the dramatic plot to the laws of vraisemblance and bienséance , the subordination of comedy to tragedy and the appeal to the authority of Aristotle , who, together with Horace , for the Propagation of an educational theater is available.

History of origin

D'Aubignac began working on Pratique du Théâtre as early as 1640 after receiving the suggestion from Richelieu , whose protégé he was and for whom he had already written the Projet pour le rétablissement du théâtre français . It contains suggestions on how the prestige of the theater should be improved at the price of its regulation. Richelieu's death in 1642 brought d'Aubignac's work at the Pratique du Théâtre to a temporary standstill, so that he did not decide to publish it until 1657 at the request of his friends. D'Aubignac begins his remarks with a list of theorists of the 16th and 17th centuries with whom he agrees on the essential points. In addition to Aristotle and Horace, the names of Castelvetro , Vida , Heisius , Vossius , Scaliger and La Mesnardière can be found . The author who is mentioned most often is Pierre Corneille . Mostly this is mentioned by d'Aubignac as a model, but not infrequently also criticized. In the course of time, a tension between the two authors has developed. Corneille seemed to have felt challenged by the Pratique and three years later (1660) published his own contribution to classical drama theory, the Trois Discours sur le Poème dramatique . Although Corneille made constant references to d'Aubignac, he was never directly mentioned by name.

content

Although the content of the Abbé's work does not develop a new initiative , but rather seeks to confirm and consolidate the previous tendency of drama theory , it has its own distinct profile in two respects. First of all, there is a strong emphasis on the theater, as d'Aubignac already indicates by the title of his treatise. Right from the start he emphasized that it was very important to him to differentiate himself from his predecessors in this area. Although he quotes Aristotle more than 60 times and even though his practice is ultimately referred back to theory again and again , it is still true that of all the theorists of the 17th century he tried hardest to convey theory and practice . For example, his advice to let the tragedy begin as close to the catastrophe as possible , because this required a high degree of concentration, proved to be particularly promising. Further, in some cases detailed information on theater practice deal with questions about the division of nudes or the management of scenes. It should also be emphasized that d'Aubignac is already considering the effect of theater on the audience in his considerations, which is already evident in the title of the sixth chapter of the first book ( Des spectateurs et comment le poète les doit considérer ).

D'Aubignac's Pratique du Théâtre consists of four books. The first book deals with the external conditions of representation and the action dramatique , to which Aubignac makes suggestions and lays down general principles. He was responding to the attacks from which contemporary theater suffered, highlighting the need to understand drama within the framework of the republic and under the prestige that the Théâtre des Anciens had in the past . He tries to connect theory with practice, for example by explaining the application of the rules of theater with the decoration of the scenes. The second book focuses on the subject matter of the pieces. Aubignac underlines the importance of the vraisemblance , the unités (units), examines the process of action (plot) and explains the tragi -comédie . In the third book, d'Aubignac describes the quantitative elements of the Poème Dramatique , such as the episodes , the chorus , the acts and scenes , monologues , subtexts and stanzas . Finally, the fourth book is devoted to expressions such as discours , narration and figures .

Vraisemblance

The concept of vraisemblance , which can be translated today with credibility and probability, has been a key point of drama theory since Aristotle's poetics . He creates a connection between illusion , reality and the idealization of the courtly world in the theory of classical theater. Although vraisemblance was a central term in drama theory even before d'Aubignac, it has hardly played such a dominant role in such an extensive context. D'Aubignac assumes that poetry is basically fiction , i.e. a lie, and therefore does not produce things, but only an imitation of them. For this reason, it is important for the author to design the imitation in such a way that it no longer acts as such, but creates the illusion of authenticity. Dramatic poetry is all the more effective the more it has the appearance of truth, that is, the more it is vrai-semblable in the truest sense of the word .

The theater near d'Aubignac is supposed to be an «image parfaite» of time, place, people, dignity, images, means and reason to act. Therefore, the representation of the circumstances must be complete and the vraisemblance must be internalized in all these areas. With regard to this finding, d'Aubignac judges what is to be allowed on the stage and what is to be condemned. Things must be true , or at least be able to be true. After this assumption, d'Aubignac approves all actions and texts that could be made plausible or said by those involved. He also relates this to all events that follow the first appearances, since one should also assume from these that they could and should probably take place in such a way. On the contrary, d'Aubignac condemns all representations of things concerning the people, the places, the time or the first appearances of the drama that should not normally be said or done. "Tant il est vrai que la Tragédie se considère principalement en soi, comme une Action véritable."

It is important that the poet should describe things in such a way that the viewer perceives them as admirable, because “il ne travaille que pour leur plaire.” According to d'Aubignac, the author should only describe the noblest incidents in history, all of his Leading characters into the most comfortable states, using the most vivid characters of rhetoric and the greatest passions of morality. In doing so, he shouldn't hide what the audience should know and enjoy, but he should refrain from those things that shock them. The vraisemblance thus becomes the most important characteristic of the Poème Dramatique for d'Aubignac , as it expresses itself in every area and tries there to represent nature in its truth and probability by imitation:

"Mais quand il considère en sa Tragédie l'Histoire véritable ou qu'il suppose être véritable, il n'a soin que de garder la vraisemblance des choses, et d'en composer toutes les Actions, les Discours, et les Incidents, comme s'ils étaient véritablement arrivés. The accorde les pensées avec les personnes, les temps avec les lieux, les suites avec les principes. Enfin il s'attache tellement à la Nature des choses, qu'il n'en veut contredire ni l'état, ni l'ordre, ni les effets, ni les convenances; et en un mot il n'a point d'autre guide que la vraisemblance, et rejette tout ce qui n'en porte point les caractères. »

In order for this to succeed, the role of the actor and his acting style are also decisive, because he must on the one hand pretend that there are no spectators present and on the other hand as if he is, for example, actually the king, and not an actor in l ' Hôtel de Bourgogne was in Paris. D'Aubignac thus describes the respect for the fourth wall , as it is still called today in the theater of the classic box theater.

Bienséance

The bienséance has its origins in Horace , but has left its mark on a wide variety of theater-theoretical texts since 1630. Above all, it is characterized by a moralizing and rationalizing aspect of art. The bienséance in turn concerns the “internal harmony” of a work, as well as the harmony between the work and the audience. Neither the taste nor the prejudices of the audience should be shocked. The bienséance includes technical principles and moral proposals, such as the decency of the ethical order, the constancy of the characters in the work or the prohibition of any suggestion of the sensual life of the characters. An example of this is the fact that no murder or death is portrayed on stage.

It follows that the bienséance, also with d'Aubignac, must be seen in harmony with the vraisemblance . Although an attempt should be made to establish the truth in a fictitious manner, this does not justify an embellishment of undesirable facts. It is true that Nero had his mother strangled and then opened her body, but such barbarities are not suitable for the theater because they are hideous and intolerable for the audience. The vraisemblance must therefore at d'Aubignac from the perspective of bienséance be considered, for not only the illusion of truth characterizes the probable; it is also above all propriety that must not contradict prevailing taste and norms. As the bienséance thus reduces the “imitable” to the “decent”, the vraisemblance is tied to the aesthetic, moral and, consequently, also to the political norms of the existing social system of the 17th century. The bienséance can also be found in German-speaking countries with Johann Christoph Gottsched , who, for example, opposed any representation of blood on stage. D'Aubignac finally recommended hiding the terrible and superfluous aspects in the theater, using the récit , the messenger report .

The three units

The three Aristotelian units , which, as their name suggests, go back to the explanations of the poetics of Aristotle, are important in many writings in the theater discourse of the 17th century and can also be found in d'Aubignac.

- The unity of the action

The unity of the plot ( L'Unité de L'Action ) specifies that only one main plot should be in the foreground in each piece, in which d'Aubignac's view largely coincides with that of Aristotle. The subplots must be subordinate to the main plot and at the same time be related to it, so that every thread and every scene of the play is justified and useful to the plot of the play. To illustrate this point, d'Aubignac compares a play and a painting:

«Il est certain que le Théâtre n'est rien qu'une Image, et partant comme il est impossible de faire une seule image accomplie de deux originaux différents, il est impossible que deux Actions (J'entends principales) soient représentées raisonnablement par une seule Pièce de Théâtre. »

"It is certain that the theater is nothing but a picture, and just as it is impossible to create a single picture from two different originals, so it is also impossible to represent two main plots in a single play."

- The unity of time

The unity of time described by Aristotle ( L'Unité de Temps ) should, according to him, take place in a “révolution de soleil”, or should only go beyond this framework in order to be representable in the theater in terms of time. D'Aubignac points out the two different ways in which this sun orbit can be interpreted: On the one hand, it could be understood as a day in the sense of 24 hours, on the other hand, it could also describe the duration between sunrise and sunset. D'Aubignac suggests setting the time to 12, 6 or even 3 hours. In the Pratique, however, he also distinguishes two types of duration that seem to be of importance to him with regard to the Poème Dramatique . The first duration is the duration of the action being performed, i.e. the duration of the performance from the first actor entering the stage to leaving the stage at the end of the play. The second duration is the already mentioned, real duration of the content presentation. If this is too long, the viewer may be bored or mentally tired. If, on the other hand, it is too short, you run the risk of not being able to entertain the audience sufficiently.

- The unity of the place

The unity of the place ( L'Unité de Lieu ) describes the striving to keep the place of action the same from the beginning to the end of the play and to avoid changing locations. This unit, ignored by Aristotle and first appeared at Castelvetro in 1570, is strongly supported by d'Aubignac. On the one hand, he argues in terms of vraisemblance and thinks it is ridiculous when people move to various places. At the same time, he argues that the location cannot change because the scene in the theater cannot be changed during the performance.

If d'Aubignac clearly emerges as a representative of the three units in his work Pratique de Théâtre , literary scholars such as BJ Bourque have already pointed out that d'Aubignac as theoretician differs greatly from d'Aubignac as a dramaturge. As a result of the analysis of his tragedies La Cyminde , La Pucelle d'Orléans and Zénobie , it could be established that d'Aubignac did not succeed in putting into practice the rules laid down in his theoretical writings. Only the Unité de Temps seems to be adhered to by him in his pieces, whereby the time frame here consequently violates the rules of vraisemblance . With regard to the Unité de Lieu and the Unité de L'Action , the analyzes always found at least one work that disregarded the rules of the units.

Reception in German-speaking countries

Published in Paris in 1657, the Pratique du Théâtre was not translated into German until 1737 by Wolf Balthasar Adolf von Steinwehr , a student of Gottsched and a member of the German Society in Leipzig. The work has been well respected since then and has had a significant impact in Germany. D'Aubignac's aim was to return with his work to the respect and prestige that the theater of antiquity had in its day. This view largely coincides with the efforts of one of the most famous theater and literary theorists in the German-speaking area, Johann Christoph Gottsched , who was also concerned about maintaining the prestige of the doctrines and tried to extol the moral power of art. Steinwehr's translation was therefore very much valued, because it enabled his compatriots to pass on the concept of a theater that conforms to the laws of reason . In the work Contributions to the critical history of the German language, poetry and eloquence , which was published by members of the Deutsche Gesellschaft in Leipzig, there is the following reaction to d'Aubignac's work:

“No country and no language can identify a work that would be so vividly, so neatly and so thoroughly written by this type of poetry. The Abbot of Aubignac does not propose the best rules which the worldly wise men have given and which the ancients have so carefully observed, not only in their order; but also proves its necessity, from the nature of the stage and from reason. "

The Pratique du Théâtre was therefore also very useful for the audience, as they now had access to the newly understandable set of rules, which they had previously been rather ignorant of. The pratique was ultimately seen as a way of closing the gaps in theater theory in Germany.

Works

tragedies

- La Cyminde (1642)

- La Pucelle d'Orléans (1642)

- Zenobie (1647)

- Le Martyre de Sainte Catherine (1650)

Theoretical writings

- Des Satyres brutes, monstres et demons , 1627

- Le Royaume de coquetterie , 1654

- La Pratique du théâtre , 1657

- Macarize , 1664

- Dissertation on the condamnation des Théâtres , 1666

- Conjectures académiques sur l'Iliade , 1715.

literature

- Aubignac, François Hédelin . In: Encyclopædia Britannica . 11th edition. tape 2 : Andros - Austria . London 1910, p. 889 (English, full text [ Wikisource ]).

Web links

- Publications by and about François Hédelin in VD 17 .

- Literature by and about François Hédelin in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bernard Croquette: Aubignac François Hédelin Abbe d '(1604-1676) . In: Encyclopædia Universalis , January 7, 2015.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Neuschäfer: La pratique du théâtre and other writings on the Doctrine classique , Fink, Munich 1971, pp. VII ff. [Nachdr. d. three. Amsterdam 1715].

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Neuschäfer:: La pratique du théâtre and other writings on the Doctrine classique , Fink, Munich 1971, pp. X ff. [Nachdr. d. three. Amsterdam 1715].

- ↑ a b Catherine Julliard: “Gottsched et l'esthétique théâtrale française. La réception allemande des théories françaises ”, Peter Lang, Bern 1998, p. 110.

- ^ Peter Brockmeier: French literature in individual representations . 1. From Rabelais to Diderot . Metzler, Stuttgart 1981, p. 125 ff.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Neuschäfer: La pratique du théâtre and other writings on the Doctrine classique , Fink, Munich 1971, p. VIV. [Repr. d. three. Amsterdam 1715].

- ^ François Hédelin abbé d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre . Hélène Baby (ed.). Édition Champion, Paris 2001, p. 126.

- ^ François Hédelin abbé d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre . Hélène Baby (ed.). Édition Champion, Paris 2001, p. 79.

- ^ François Hédelin abbé d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre , Hélène Baby (ed.), Édition Champion, Paris 2001, p. 81.

- ^ François Hédelin abbé d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre . Hélène Baby (ed.). Édition Champion, Paris 2001, p. 81.

- ^ François Hédelin abbé d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre . Hélène Baby (ed.). Édition Champion, Paris 2001, p. 81.

- ^ François Hédelin abbé d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre , Hélène Baby (ed.), Édition Champion, Paris 2001, p. 82.

- ↑ a b Catherine Julliard: Gottsched et l'esthétique théâtrale francaise. La réception allemande des théories francaises . Peter Lang, Bern 1998, p. 98.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Neuschäfer: D'Aubignac's “Pratique du Théâtre” and the connection between “imitatio”, “vraisemblance” and “bienséance” . In: François Hédelin d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre and other writings on the Doctrine classique . Fink, Munich 1071, p. XV.

- ↑ Hans-Jörg Neuschäfer: D'Aubignac's “Pratique du Théâtre” and the connection between “imitatio”, “vraisemblance” and “bienséance” . In: François Hédelin d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre and other writings on the Doctrine classique . Fink, Munich 1071, p. VII.

- ^ François Hédelin abbé d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre . Hélène Baby (ed.). Édition Champion, Paris 2001, p. 152.

- ^ François Hédelin abbé d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre . Hélène Baby (ed.). Édition Champion, Paris 2001, p. 133.

- ^ François Hédelin abbé d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre . Hélène Baby (ed.). Édition Champion, Paris 2001, p. 181.

- ^ François Hédelin abbé d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre . Hélène Baby (ed.). Édition Champion, Paris 2001, p. 172.

- ↑ Catherine Julliard: “Gottsched et l'esthétique théâtrale francaise. La réception allemande des théories francaises ”, Peter Lang, Bern 1998, p. 103.

- ^ François Hédelin abbé d'Aubignac: La Pratique du Théâtre . Hélène Baby (ed.). Édition Champion, Paris 2001, p. 53.

- ^ BJ Bourque: Abbé d'Aubignac et ses trois unités: théorie et pratique . In: Papers on French Seventeenth Century Literature , 2008, Vol. 35 (69), (pp. 589-601), p. 593.

- ↑ a b Catherine Julliard: Gottsched et l'esthétique théâtrale francaise. La réception allemande des théories francaises. Peter Lang, Bern 1998, p. 110.

- ^ Catherine Julliard: Gottsched et l'esthétique théâtrale francaise. La réception allemande des théories francaises. Peter Lang, Bern 1998, p. 58.

- ^ BB Christoph Breitkopf (ed.): Contributions to the critical history of the German language, poetry and eloquence. Published by some members of the German Society in Leipzig. Bavarian State Library, Leipzig, Volume 5, 1737.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hédelin, François |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Aubignac; François Hédelin, Abbé d ' |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French writer theoretician of theater |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 4th August 1604 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Paris |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 25, 1676 |

| Place of death | Nemours |