Francis Younghusband

Sir Francis Edward Younghusband (born May 31, 1863 in Murree , India , † July 31, 1942 in Lytchett Minster, Dorset , United Kingdom ) was a British explorer , officer, religious philosopher and non-fiction author.

At the age of just 24, Younghusband was accepted into the Royal Geographical Society and awarded its gold medal. He is the youngest person ever to be elected to this prestigious society and received this award for his crossing of the Gobi desert and his crossing of the Karakoram Mountains. Younghusband was also an excellent athlete : for a time he held the world record over the 300-yard distance. At the beginning of the 20th century he was one of Britain's most famous explorers, portrayed in the British press as a daring soldier and a great gentleman. Younghusband is also responsible for the massacre at Guru in the context of the British Tibet campaign of 1904. However, his experiences in Tibet also led to a turn to religious questions. In 1936 he founded the World Congress of Faiths . He also supported India's aspirations for independence from British colonial rule.

As president of the Royal Geographical Society , Younghusband was instrumental in helping three British expeditions to the Mount Everest area in the 1920s. While the first aim was still to map the area, the express aim of the second and third expeditions was to secure the first ascent of the highest peak in the world for Great Britain. The last of these expeditions ended in 1924 with the death of George Mallory , one of the best climbers of his generation, and his companion Andrew Irvine .

Life

His grandfather was Major General Charles Younghusband (1778–1843) and so it is hardly surprising that Francis' father, Major General John William Younghusband (1823–1907), also embarked on a military career, as did his sons. His father was Major General John William Younghusband (1823-1907), who had participated under Charles James Napier in the campaign to conquer Sindh in 1843 and later he fought under John Nicholson , who prevented the uprising in Peshawar from spreading. Because of an injury he was at home in England and on February 21, 1856 married Clare Jane Shaw, the sister of the well-known Central Asian researcher Robert Shaw . His parents bought land in the Kangra Valley in 1856 to build a tea plantation, so Francis was born in Murree . Frank, as he was called in the family, had an older brother, George John, who was born in 1859 and also served in the army and with whom he helped to relieve Chitral. Together they wrote the book about the Chitral campaign . Major General Leslie Napier Younghusband was his younger brother and Emmie was his unmarried sister who lived with her parents.

He was sent to Clifton College in Bristol for schooling by his parents and then attended the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst .

First explorations in the Himalaya region

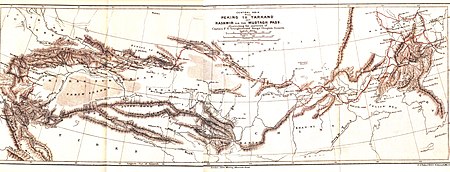

In 1882, when he was 19 years old, Younghusband joined a regiment stationed in India. In 1886, after several exploratory expeditions into the Himalayas and explorations along the Indus and the Afghan border, he became a member of an expedition that led to Manchuria . After seven months in the field, Younghusband found himself alone in Beijing and had to return to India from there. He decided to return the route on foot. He was the first European to cross the Gobi Desert and the Karakoram via the Muztagh Pass . A year later, the Younghusband, who had meanwhile been promoted to captain, returned to the Karakoram Mountains. The expedition was supposed to investigate attacks on trade caravans, but the actual aim was to explore the passes and rivers that ran through the mountains and to find out how far the region had been infiltrated by Russian agents. One of the officers who was also involved in this expedition was Charles Granville Bruce , who, together with Younghusband, provided essential support for the British Mount Everest expeditions in the 1920s. This area represented one of the most problematic border regions to the British Empire and British politicians and military feared an advance of Imperial Russia in this region . The Russian advance almost triggered a war between India and Imperial Russia .

Between 1889 and 1895 he was involved in several expeditions to the north-west Indian mountains. During one of these explorations in the summer of 1891, Younghusband was captured by a Cossack patrol and forced to return to India. The incident sparked a serious diplomatic crisis between Britain and Russia. At Younghusband, the incident led him to take the Russian threat on this frontier of the British Empire very seriously. He shared this conviction with Lord Curzon , whom he met in 1893 when Curzon was still a young member of the British Parliament and also carried out exploratory expeditions in India.

Tibet 1903 and 1904

Background: British and Russian competition for supremacy in Central Asia

In April 1903, Younghusband was sent to Tibet by Lord Curzon to establish trade relations with the country. These negotiations took place at the time of the so-called Great Games , the race between Russia and Great Britain for supremacy in Central Asia. He was directed against the diplomatic influence of the Russian Empire on Tibet and took advantage of the fact that Russia was militarily bound due to the tensions with the Empire of Japan and later by the Russo-Japanese War . Both Lord Curzon and Francis Younghusband felt pressured to act because they were falsely convinced that the Mongolian lama Agvan Dorzhiev was negotiating with the Tibetans for the Russian Empire. The reason for these fears, which have been prevalent on the British side since 1900, were, among other things, several Russian newspaper reports from 1900 and 1901 that the Lama had delivered a letter from the Tsar to the Dalai Lama in 1900 and Dorzhiev followed him with a delegation of Tibetan monks just under a year later Russia returned. They had also been informed by the Japanese monk Ekai Kawaguchi that Russia was delivering weapons to Tibet and that another 200 Mongolian monks lived in Tibet, which would have made it easy for Russia to spy on the country. This information also ultimately turned out to be incorrect.

The failed attempt to establish diplomatic relations with Tibet

Britain's diplomatic efforts to establish trade relations in 1903 failed, not least, as Wade Davis points out, because of a fundamental cultural misunderstanding on the British side.

Younghusband was accompanied by Captain Frederick O'Connor, the only person in the British Army who spoke Tibetan, and 500 sepoys . In Gangtok, Claude White, actually the political officer in Sikkim, joined the expedition group. The Chinese-speaking Claude White was supposed to serve as interpreter for the expedition. Younghusband first sent his troops ahead while he waited at the Tibetan border from July 4, 1903 until the British camp below the fortress was set up in Kampa Dzong , a small town just across the Tibetan border. On July 18th he rode in there with all diplomatic honors. Younghusband waited in vain for frustrating months in Kampa Dzong for Tibetan officials to arrive to negotiate with him. " I have never met such obstinate and obstructive people, " said Younghusband.

The Tibetans, on the other hand, had no interest in dialogue, especially none that took place on their own territory. They insisted that there would be no negotiations until British forces withdrew behind the border. Eline negotiations were also not possible because the 13th Dalai Lama Thubten Gyatsho had withdrawn to a three-year meditation and without him no essential decisions could be made. The British expedition passed the waiting time with hunting, horse racing and collecting plants. After several months of in vain waiting, the British representatives were ordered back to India. For the Tibetans, however, their success turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory . The British took the first opportunity to assert their interests by force of arms.

The Tibet campaign and the massacre at Guru

occasion

Towards the end of 1903 a small group of Tibetan soldiers crossed the border, stole a herd of Nepalese yaks and drove them into Tibet. Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India and thus ruler of 300 million men and women, this incident provided the welcome occasion to inform the British government on November 3, 1903 of a hostile act on the part of the Tibetan military and Younghusband with a military expedition, the so-called British Tibet Campaign to entrust to Tibet. The task was to penetrate as deeply as possible into Tibetan territory, but in no case further than the fortress of Gyangzê , halfway to Lhasa . This show of British strength was intended to force the Tibetans to the negotiating table. The Russian government protested against this practice.

The British gathered a total of 5,000 men in Darjiling and Gangtok in early December . Most of them were Gurkhas and Sikhs , but also pioneers, engineers, artillery and machine gun units of the regular army, as well as military police, medical staff, experts in telegraph services and diplomats. They were accompanied by a handful of journalists who were supposed to report on the project for British newspapers. 10,000 porters and 20,000 yaks, who were supposed to ensure the supply of the troops, also took part in this military expedition. On December 13th, Younghusband crossed the Jelep La Pass near Kalimpong , which led into the Tibetan highlands. His troops followed the Chumbi valley towards Gyantse for three weeks and then reached the Tibetan plateau. Younghusband decided to set up his winter camp here. His military commander, General James MacDonald of the Royal Engineers, found the position Younghusband had chosen too exposed in the face of the winter weather. He withdrew again into the Chumbi Valley while the diplomatic part of the expedition, accompanied only by a small military unit, stayed on the high plateau and negotiated with the Tibetans. The Tibetans insisted that the Mongolian Lama Dorzhiev was staying with the Dalai Lama for religious reasons only, that there was no diplomatic relationship between Tibet and the Tsarist Empire, and that there was no alliance between the two countries. Wade Davis points out that by then the British were too committed to accept this as the true truth. In March, Younghusband ended the negotiations and decided that the expedition should advance further towards Lhasa, although one could be sure that the Tibetans would give up their non-fighting behavior if they made further advance.

The Guru massacre

At the end of March, the British troops crossed a flat plain and came across several thousand Tibetan soldiers at Guru's. Some sat on ponies, armed with old-fashioned muzzle - loaders , slingshots, axes, swords and spears. The British marched towards this collection of Tibetan soldiers in the formation typical of the British Army: First the infantry, behind them the artillery and the Maxim machine guns on the sides. The British expectation that the Tibetan troops would withdraw in the face of British arms superiority was not fulfilled. Eventually the two troops faced each other and General James MacDonald gave the order to disarm the Tibetans. When one of the British soldiers grabbed the reins of a Tibetan general, the latter drew his pistol and shot the soldier in the face, whereupon the Maxim machine guns opened fire. Davis calls the British victory just another of those effortless victories by a colonial power against hopelessly inferior locals, comparing it to the Battle of Omdurman . The Tibetans did not surrender in this battle, but withdrew slowly while the British did not stop the fire for unexplained reasons. While eight soldiers and one journalist were wounded on the British side, more than six hundred Tibetans died and countless others were injured.

The massacre already caused horror among those present. Younghusband called the incident horrific, one of the British officers wrote to his mother that he hoped he would never again have to shoot men who were simply leaving and Henry Savage Landor , one of the British correspondents present, called it in his report to London a slaughter of thousands of helpless and defenseless locals that must be repugnant to anyone who is a man.

Lhasa

The Tibetan troops withdrew further north and British troops followed them. There were a number of small skirmishes and finally a two-month siege of the Gyangzê fortress, during which the British suffered ten casualties and the Tibetans some five thousand. On August 3, 1904, Younghusband reached Lhasa , which so far had only been reached by a few Europeans.

Lhasa turned out to be a great disappointment: The Dalai Lama Thubten Gyatsho had interrupted his retreat for meditation and fled into exile in Mongolia. He didn't return until five years later. Younghusband found it difficult to find people on site to negotiate with. An attempt to replace the Dalai Lama with the Panchen Lama Thubten Chökyi Nyima failed. After mediation by Ugyen Wangchuk , the future king of Bhutan, who had accompanied the British military expedition, Younghusband ultimately found four members of the Tibetan cabinet, the so-called Kasgar, to whom he could dictate his terms. Signed September 7, 1904, these agreements gave the British control of the Chumbi Valley for the next 75 years, allowed free access to Lhasa for a British commercial agent, and prohibited Tibetans from negotiating with other foreign powers unless the UK had previously consented.

Younghusband found no traces of Russian activity in Tibet: there was no arsenal or railroad. Indeed, the Mongolian lama Agvan Dorzhiev seemed nothing more than a simple monk. Edmund Chandler, who had accompanied the expedition for the Daily Mail , stated for his readers that the idea that British colonial rule could be endangered by an advance of Tsarist Russia into geographically isolated and so inaccessible Tibet was absurd. On September 23, 1904, the British expedition left Tibet because they feared the beginning of winter.

Aftermath of the British Tibet campaign

Younghusband received confirmation from both Edward VII and Lord Curzon and Lord Ampthill , who briefly represented Curzon as Viceroy of India. However, neither the British government nor any part of the British, continental European or Indian press shared this positive assessment of the expedition. The British government tried by telegram to force Younghusband into new negotiations in which, among other things, the condition that a British commercial agent could settle in Lhasa should be waived. Younghusband, however, considered it impossible to resume negotiations because of the advanced season and ignored these instructions. In the press, the advance of British troops was described as an imperialist anachronism and those responsible were accused of pointless pursuit of glory. Winston Churchill , a Liberal politician at the time, spoke out in favor of Tibetans' right to defend their homeland.

Wade Davis points out that Younghusband left Lhasa as a changed person. As a farewell, a high lama presented him with a representation of Buddha as a peace gift. Younghusband carried this icon with him all his life. His daughter had him buried with this in his coffin in 1942 and his tombstone is adorned with a relief from Lhasa. He devoted himself increasingly to the goal of tearing down the barriers between the great world religions and Davis admits that he was very open to other cultures compared to his contemporaries. Lawrence James sees this change in his history of the British colonial empire in India much more cynically. Younghusband's career path was blocked after this expedition and would have had to look for new paths, which ultimately led to a quirky mysticism.

Other work

Younghusband settled in Kashmir in 1906 as the British envoy. In 1910 he retired from military service. He wrote expedition reports and several books on religious and philosophical questions.

Works

- Younghusband, Sir Francis: The Himalayas are calling , translated by Heinrich Erler, Union Deutsche Verlagsgesellschaft Roth &. Co., Berlin 1937, (English original title: Everest, the Challenge )

- Younghusband, Francis: La epopeya del Everest , 1946, Barcelona, Ed. Juventud

- German: Der Heldengesang des Mount Everest , translated by W. Rickmers Rickmers; B. Schuster & Co., Basel 1928 (English original title: The Epic of Mount Everest )

- Younghusband, Sir Francis: The Heart of Nature; or, The Quest for Natural Beauty . Publisher: John Murray, London 1921. A Projekt Gutenberg book.

- German: The heart of nature , FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1923

- KASHMIR described by Sir FRANCIS YOUNGHUSBAND, KCIE PAINTED BY Major E. MOLYNEUX, DSO Publishers Adam and Charles 1911. First published September 1909. A Projekt Gutenberg book.

literature

- Wade Davis: Into the Silence: The Great War, Mallory and the Conquest of Everest. Vintage digital. London 2011, ISBN 978-1-84792-184-0 .

- Patrick French: Younghusband. The Last Great Imperial Adventurer . HarperCollins, London 2004, ISBN 0-00-637601-0 . (English).

- Hopkirk Peter : The Great Game. On Secret Service in High Asia. John Murray (Publishers) Ltd., London 1990. ISBN 0-7195-4727-X . (English).

- Lawrence James: Raj. The Making of British India. Abacus, London 1997, ISBN 0-349-11012-3 .

- Tsepon WD Shakabpa: Tibet. A Political History. 4. Pressure. Potala Publishing, New York NY 1988, ISBN 0-9611474-1-5 .

- Gordon T. Stewart: Journeys to Empire, Enlightenment, Imperialism, and the British Encounter with Tibet, 1774-1904 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-73568-1 .

- Jeffrey Archer: "Paths of Glory" McMillan, London, 2009, ISBN 978-3-596-18650-1

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Wade Davis: Into the Silence . P. 54.

- ^ World Congress of Faiths' History

- ↑ Wade Davis: Into the Silenc . P. 5.

- ↑ Sapoy Uprising 1857-58 University of Augsburg

- ^ Lt.-Col. Sir Francis Edward Younghusband on thepeerage.com , accessed September 15, 2016.

- ^ The relief of Chitral.

- ↑ Clifton College heritage

- ↑ Wade Davis: Into the Silence . P. 53

- ^ Hopkirk Peter: The Great Game. On Secret Service in High Asia. John Murray (Publishers) Ltd., London 1990. Pages 469-470.

- ^ A b Wade Davis: Into the Silence . P. 52.

- ↑ a b c d e Wade Davis: Into the Silence . P. 55.

- ↑ Wade Davis: Into the Silence . P. 55. In the original Younghusband wrote: Never have I met so obdurate and obstructive a people.

- ^ A b c Wade Davis: Into the Silence . P.56.

- ↑ Wade Davis: Into the Silence . P. 57.

- ↑ a b c d e Wade Davis: Into the Silence . P. 58.

- ^ A b Wade Davis: Into the Silence . P. 59.

- ^ A b Wade Davis: Into the Silence . P. 60.

- ^ Hopkirk Peter: The Great Game. On Secret Service in High Asia. John Murray (Publishers) Ltd., London 1990. Pages 509-512, 517-519

- ^ A b Wade Davis: Into the Silence . P. 61.

- ↑ a b Lawrence James: Raj. The Making of British India. , P. 391

- ↑ Wade Davis: Into the Silence . P. 62.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Younghusband, Francis |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Younghusband, Francis Edward |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British officer and explorer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 31, 1863 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Murree , India |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 31, 1942 |

| Place of death | Lytchett Minster |