Gandy dancer

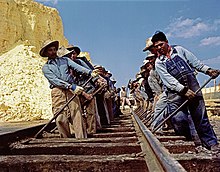

In the United States , " gandy dancer " used to be a slang term for line workers who laid and maintained tracks before machines did this job. These line workers were officially called "section hands". In Great Britain , the equivalent of gandy dancer in the case of railway construction workers is “navvy” (from the English word for seafarer “ navigator ”). These unskilled workers were initially responsible for building canals and inland waterways . The track keepers , whose job was the maintenance and servicing of tracks, were called "platelayer" in Great Britain . In the southwestern United States and Mexico , these Mexican and Mexican-American line workers were colloquially called "traqueros," a name derived from the Spanglish word for track.

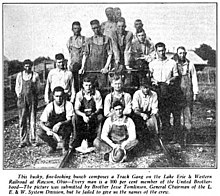

In the United States , route workers were often recently arrived immigrants and ethnic minorities who competed for these secure jobs despite poor pay, poor working conditions and hard physical labor. In the western United States it was the Chinese, Mexican Americans, and Indians , in the Midwest it was the Irish, and in the northeast it was the Italians and Eastern Europeans who worked as gandy dancers. While all gandy dancers sang songs about the railroad while they were working, the work chants related to specific activities were sung only by the African-American gandy dancers from the southern states , probably due to their long tradition of coordinating work through singing .

There have been several theories about the origin of the term, but most of them refer to the "dancing" movement that track workers made while working with a custom-made 1.52 meter crowbar . This crowbar was also called "gandy" and was used as a kind of lever to straighten the rails.

etymology

The origin of the term is unclear. Most of the first line workers in the north were Irish. Hence, it is possible that the term was derived from an Irish or Gaelic expression.

Other theories suggest that the term gandy dancer may have developed as a description of the movement of the line workers themselves. This movement was the permanent "dancing", for example when they were simultaneously swinging their tools to align the tracks and the beat was often given by chants; or if they carried the rails; or perhaps even because of Watschelns as Ganter (English: gander) when the sleepers were running.

Most researchers, however, have come across the Gandy Shovel Company, sometimes called the Gandy Manufacturing Company or Gandy Tool Company, which existed in Chicago and made the tools that gave Gandy dancers their name should have. Some sources even list the goods made by the company, e.g. B. "Rammer plates, cow feet, pickaxes and shovels". Others, however, doubt the existence of such a company. The Chicago Historical Society has been asked for information about this company so many times that it said it was "like a legend," but the club has also been unable to find any records of a company called Gandy.

history

Although rails were held in place by wooden sleepers and the bedding, due to the centripetal force and vibrations acting on the rails, they shifted a tiny bit every time a train went through a curve. The rails therefore had to be regularly repaired by line workers, since heavily displaced rails could lead to derailment in the worst case.

For each push, a worker would raise his crowbar , the so-called gandy, and drive it into the gravel in order to have a lever point. Then he would throw himself against the bar with his full body weight (making the "Huh" sound that was built into the lyrics below), causing the bar to push the track towards the inside of the curve.

This step is explained in the folklore section of the Alabama Encyclopedia as follows:

“Each worker carried a straightening bar, a straight crowbar with a pointed end. The thicker, lower end had a rectangular shaft (to fit the track) and was shaped like a pointed chisel (to poke into the gravel under the track); the lighter, top end was rounded to allow workers to hold the bar better. While straightening the tracks, each of the workers stood in front of one of the rails and pushed the chisel-shaped end down at an angle into the ballast below. Then all workers would take a step on the tracks and lever the respective track, including rails, sleepers , etc., up over and through the ballast with their crowbars. "

The line workers also had to pry open the rails at regular intervals to compensate for the lowered areas. Side by side, they lifted the rails with a square hoe and pushed ballast under the sleepers. Even with teams that consisted of eight, ten or more workers, progress was only noticeable after many repetitions of this process when moving the rails.

To maintain the tracks, Gandy dancers used not only crowbars but also special sledgehammers , also known as spike maws, to hammer in nails, shovels or ballast forks to distribute track ballast , large tongs (so-called rail dogs) to carry the rails, and ballast Rammers or hoes to evenly distribute the crushed stone. The same crews also performed other rail maintenance tasks, such as removing weeds, unloading sleepers and rails, and replacing worn tracks and rotten sleepers. The work was extremely hard and the wages low, but it was one of the few jobs available to southern blacks and new immigrants at the time. Blacks who were employed as route workers were held in high regard by their own kind. The text of a blues song reads: "If you get married, marry a line worker, because then you can look forward to a windfall every Sunday".

Economic circumstances of line workers

In a 1918 article for Harper's Magazine on Industrial Workers of the World (IWW ), Robert W. Bruere explained the economic circumstances that sometimes led gandy dancers and other migrant workers to join this organization:

The divisional manager of a major US railroad recently explained to me his role, which he reluctantly accepted, in creating the socially disintegrated conditions that gave birth to the migrant workers and rebellious propaganda of the IWW. "The men in the East," he said, "the men who have invested their money in our streets measure the efficiency of our administration in terms of return on money, net income and dividends. Many of our shareholders have never seen the land on which our road was built. They get their impression of the country and the people not through the contact with the men, but through the impersonal ticker. They judge us on the basis of the stock exchange listing and balance sheet. The end of the story is that we have the costs so far like a jailer's hair. Examples of this would be the maintenance of tracks, such as the maintenance of tracks and roadbeds. This should actually last most of the year. But to keep costs down, we have everything in four months It is impossible to find the number of men with the skills and knowledge we need for this four month job, so we publish A that look something like this:

Men wanted! High wages!

Permanent employment!

“We know, when we put our money into such advertisements, that they are - well, part of a dangerous system of sabotage. We know that we will not offer anyone a permanent position. But we attract men with false promises and they come. After the four months we release them again, they are strangers in a strange land and many of them are thousands of kilometers from their old home. You are not our problem. They come here with big dreams and many of them think they will build houses, support their families and become permanent US citizens here. After a few weeks all their savings are used up, the single men become more and more restless and move on. A few more weeks later, the married men also say goodbye to their families. You set out to look for jobs. When they find permanent employment, their families bring them up; some of them get on the freight trains and drive to the next town. They are broke when they get there, the job market is overcrowded and the odds are high that they will end up in jail as a tramp. Some of them go into the forest, to the ranches and mines. Many of them never find a secure job again. They become hobos, vagrants , migrant workers, and are outcasts in society and industry ripe for the deprived community of the IWW. " the powerful suction of our hasty industrial expansion was developed ... "

Thomas Fleming , a black historian and journalist, began his professional career as a bellhop and then spent five years as a cook on the Southern Pacific Railroad . In a weekly series of articles, he wrote about his memories as a route worker in Mexico in the 1920s and 1930s. He remembers that the Southern Pacific Railroad provided them with sleeping facilities: old, converted freight cars, each with two rooms. The company took old freight cars, removed the wheels and put them next to the tracks. He recalls that the workers had many children who went to public schools, but those he met during his childhood were "kind of submissive and were often scolded and teased by the other children." Fleming says, "The Wagons were just outside of all the cities in California, they were part of the landscape. ”In his opinion, they were the only ones willing to do such a job, as they were getting the lowest wages of any other railroad worker - just about $ 40 per month.

In the early 1940s, when the US was involved in the fighting of World War II , the days of Rosie the Riveter , a few women also worked as gandy dancers. So many men were gone during the war years that the US struggled with a significant labor shortage, and women ended up doing what had hitherto been exclusively men's business. A 1988 article that appeared in The Valley Gazette reported several local women who had worked as gandy dancers on the Reading Railroad in Tamaqua , Pennsylvania . In an interview, Mary Gbur, one of the women, said it was the money, around $ 55 a week, that attracted her back then. “Money was tight and I wanted to enable my children to continue their education after high school. And it was more than the $ 18 I got at the cheap store. ”Gbur described the work as“ gruesome and boring ”and apparently it was considered humiliating by the townspeople for a woman to do manual labor, which led to that these women were embarrassed to have such a job. However, she said: "One day this attitude changed when someone said loudly and clearly, 'I am very proud of you, ladies!'". These were the words of the village priest.

Early use of the term

According to British etymologist Michael Quinion, the term gandy dancer was first used (in print) in 1918. However, since not much is known about the origin of the term, the exact time of its origin cannot be determined. In an article in the May 1918 issue of The Outlook (New York) weekly magazine, the question "What is a gandy dancer?" The article said:

What is a "gandy dancer"? The term was written on a sign outside a store near Bowery Street in Manhattan . In the past, this might have indicated a cheap dance establishment nearby, but the Bowery has changed. Today there are more than a few “Labor Bureaus” (comparable to a day laborer's house) within a block of houses, where work is mediated instead of the earlier diners and the so-called “Suicide Halls”, restaurants that guests often never left alive. According to an Italian employee of such an office, a "gandy dancer" is a line worker who stamps the earth between the sleepers and looks as if he is "dancing" on the tracks. The message on the sign read:

Men wanted for track work ashes gravel no stones work regardless of whether sun or rain weekly pay very good furnished accommodation. Board and lodging $ 5 per week. A good job, especially for seasoned gandy dancers. Just a few miles outside and get there and back quickly.

The term "gandy" is used in a story that appeared in an August 1931 issue of Boy's Life, a magazine published by the Boy Scouts of America for boys ages 6-18. The story is about the roughly 17 or 18 year old Eddie Parker, who is described as a typical American patriot and who accepts a job as a route worker. His new colleagues are all Italian immigrants, also known as "snipes" in history. The "Snipes" are described as lazy, stupid and lovers of garlic, olive oil and Italian music. Eddie manages to trick the Italians into pumping the trolley by making use of their love of music. The draisine was used to get to the respective track sections on which the line workers worked on a given day. He says that he “ attached a barrel organ to the lower frame and connected the handle to the crank axle. The handle of the barrel organ turned with every rotation. ”In the story the workers are referred to as track workers, but the trolley is called“ gandy ”.

In the 1960s, Oregon track supervisors still called track workers "gandy dancers," and the crowbar that workers used to push was called the "gandy pole" or simply "gandy" by most workers .

Songs and singing

While most of the track workers in the southern states were African American , the gandy dancers were not all African American or southern. The route workers were often immigrants and ethnic minorities who vied for a secure job despite poor wages, poor working conditions and heavy physical labor. In the west, workers from China , Mexico, and Native Americans also repaired and maintained the rails; in the Midwest, the Irish were; and in the northeast, Eastern Europeans and Italians. While all gandy dancers sang songs about the railroad while they were working, the work chants related to specific activities were probably only sung by the black gandy dancers because of their long tradition of coordinating work through chanting.

A rhythm was important both for synchronizing work processes and for the mood among the workers. So-called work songs ( work songs ) and calls, which followed the call and response principle (call and answer), served as a means of coordinating the various tasks of the track work. Slower chants, so-called dogging calls, conducted the picking up and handling of the steel rails as well as the unloading, dragging and stacking of the sleepers, and more rhythmic songs guided the alignment and nailing of the rails and the tamping of the ballast bedding.

In 1939, John Lomax recorded several songs about the railroad , including an example of an "unloading the steel rails" call, available on the American Memory website of the US Library of Congress . The song “Take This Hammer” ( available on Youtube ) by the American blues singer Leadbelly is probably based on these working chants.

It is obvious that country singer Jimmie Rodgers was also influenced by the work songs of the Gandy dancers. His father was a track foreman in Meridian , Mississippi , and took him to work as a water carrier, where he witnessed the chants himself. Rodgers would later become known as the "Singing Brakeman" and the father of country music.

Anne Kimzey of the Alabama Center For Traditional Culture writes: “All black gandy dancers used songs and chants as tools to perform certain tasks and to send encrypted messages without being understood by the foreman or others. The lead singer formulated a call to his workers, for example to realign the rails. His intention was to improve the physical and mental health of his workers while coordinating the work at hand. It took a skilled and sensitive lead singer to choose the right reputation for the job and the mood of the men. Each lead singer had his own characteristic reputation, which was based on the typical blues in terms of pitch and type of melody . How successfully a cantor can urge his men on is similar to the way a preacher can motivate his congregation. ”Typical songs consisted of two lines and four bars, to the rhythm of which the workers hit their crowbars against the rails until the men were in sync, and then the lead singer called for them to pull tight on the third of the four bars. Experienced groups of workers often adorned their work while aligning the rails with sweeping gestures of one hand and a step backwards with one foot on the first, second and fourth bars, pulling the crowbar with both hands on the third bar. Here is an old video on gandy dancers depicting the singing, dance-like rhythm, crowbar, and a very large group of workers (note that there is no ballast here, probably to make it easier to line up the rails, unlike what many sources report):

documentation

In 1994 folklorist Maggie Holtzberg, who was doing field research to document traditional folk music in Alabama, produced a documentary called Gandy Dancers. Holtzberg reports:

“Since the professional art of calling (singing to set a rhythm) was only going to exist in the memories of retired route workers, I wanted to track down former route workers and find out and document everything from their passive knowledge of the work songs - before that more was possible. First, I contacted contacts from railway companies. When I explained that I was looking for Gandy dancers to interview, there was often a short silence and then the puzzled question came, how did I know about this obscure tradition? A man laughed and said that I would have to contact a medium because workers' groups for track work were abolished in the 1960s. However, there was some promising evidence as well. The owner of a railroad maintenance company recalled "a caller who had a very high-pitched voice and could" sing "ten hours a day without repeating a chant." He too thought it was important to document what was left of the calling tradition. However, he was of the opinion that “a man alone would not be able to explain even remotely what it took to straighten rails. You have to find a whole group of line workers to do this, "and that's exactly what we did in the end."

It had been many years since modern machines had replaced line workers, so Holtzberg spoke to older or retired foremen who might remember the callers or know where they might be living. She managed to track down some callers and interview them in their homes. However, it was difficult for the men to remember the chants in their living rooms without the rhythmic tapping of the bar. So they met at a nearby railroad club that was converting a depot into a museum. In these familiar surroundings, the men quickly remembered the old work songs, especially when a train passed by and whistled loudly. Holtzberg remembers the words of John Cole, who at 82 was the oldest of the men:

"Listen to that train. Yeah! That's a train! The hawk and buzzard went up north… You hear it blowing. I got a gal live behind the jail ... That's a train ... "

("Listen. Yeah! It's a train! The falcon and buzzard flew north. You can hear him whistling. I know a girl who lives behind the jail. ... It's a train ...")

The sound was enough to get the memory off the ground. The train signal sounded and it rushed past with a Doppler effect .

The film was completed in 1994 and is available on the Folkstreams website. The trailer for the film can be found on YouTube .

Typical texts of the track construction sections

The men were motivated and entertained at the same time by the lead singer, who also set the rhythm of the work with the work songs . This work came from songs from the call and response traditions, from Africa and through the shanties " shanties were transferred", and more recently the work songs of the cotton crop , the Blues and African American church music. A good lead singer could audition all day without repeating a song. He needed to know the best work songs for each team and occasion. Sometimes work songs with a religious theme were used, sometimes those with sexual imagery were appropriate. An example is the following:

I don't know but I've been told

Susie has a jelly roll

I don't know ... huh

But I've been told ... huh

Susie has ... huh

A jelly roll ... huh

(I didn't know myself, but I was told

that Susie has a jelly roll.

I didn't know myself ... huh

But I was told ... huh

That Susie ... huh

A jelly roll has ... huh)

In these work songs, the workers used the first two lines of text to hit their crowbars against the railroad tracks and be in time and in unison. Then they threw their weight against the bars with every "Huh" sound in order to straighten the tracks.

Up and down this road I go

Skippin 'and dodging a 44

Hey man won't you line 'um ... huh

Hey won't you line 'um ... huh

Hey won't you line 'um ... huh

Hey won't you line 'um ... huh

(I go up and down this way

And hop away with a 44 Magnum

Hey man, just line them up ... huh

Hey, straighten it out ... huh

Hey, straighten it out ... huh

Hey, straighten them out ... huh)

Retired Gandy dancer John Cole explained the nails in the documentary "Gandy Dancer."

“Gandy dancing goes hand in hand with music. It has always been like that. At the beginning you had to align the railway lines. This is where the gandy dancers came in. You could even gandy dance with a sledgehammer. Even when nailing down you could make the sledgehammers talk; something was sung to them. Like when you drive a nail in. [SINGING] “Big cat, little cat, tiny kitten. Big cat! ”You drove the nail in as hard as you could. People shouted, "Make a wheel out of the hammer." That meant fast pinning. And so you could get the sledgehammer to talk with two men while driving your nails! "Big cat, small cat, tiny kitten," and the nail was already stuck. "

In 1996, two former lead singers, John Henry Mealing and Cornelius Wright, received National Heritage Fellowship awards for "Leading Folk and Traditional Artists" for their performance of this form of African American folk art.

Marching songs

A march song, or march for short , is a traditional call and response work song in the military, which is sung by soldiers while they run and march. As is customary with work songs, marching songs take over the rhythm of the work that is being done. Many of these marches have a call and response structure in which one soldier starts a line and the other soldiers have to complete it. This encourages collaboration and camaraderie . Just like track construction songs, marching songs are used to mock a superior, to vent anger and frustration, to remedy boredom and to lift the mood with jokes and boasting.

It is said that Private Willie Lee Duckworth Sr, who was stationed in Fort Slocum, New York as one of eight colored infantrymen in 1944 , came up with the marching song "Sound Off", also known as the "Duckworth Chant" and up used today in the US Army and other areas of the military. Media scholar Barry Dornfeld, who co-writes the documentary Gandy Dancer, believes Duckworth's marching songs were influenced by his familiarity with track construction songs. Dornfeld writes: "I recently noticed a connection between the African American southern tradition of call and response work songs and the marching songs in drill exercises." He continues:

“ Born in Washington County , Georgia , in 1924, Duckworth would have been familiar with the use of work songs sung in all kinds of farm work. He also came from the same generation of gandy dancers who sang songs while straightening tracks. At the time Duckworth was called up for World War II, he was working in a sawmill . In March 1944 he was sent to a makeshift training facility in Fort Slocum, New York . There, Duckworth allegedly improvised his own drill for the soldiers of his unit on the orders of a non-commissioned officer. Soon afterwards everyone was humming and keeping the rhythm in all ranks. Colonel Bernard Lentz, the fort's base commander, turned to Duckworth and asked how he came up with this singular song. Duckworth said: “I told him that was how we used to get pigs back into the barn. I was scared and at that moment I couldn't think of anything else. "

reception

The Gandy Dancer State Trail is an approx. 75 km long bike and hiking trail that climbs up the disused railway line of the former Minneapolis railway company , St. Paul and Sault Ste. Marie of St. Croix Falls, Wisconsin, runs a short distance in eastern Minnesota to Superior , Wisconsin . In Danbury , Wisconsin, the Gandy Dancer Trail is frequented by many hikers and tourists eager to walk the path that the hunter James Jordan followed in 1914 when his record stag tracked. Jordan ultimately shot the white-tailed deer with his 0.25-20 Winchester along the Yellow River. Since 1914, the so-called James Jordan Buck has been considered the largest white-tailed deer in the USA according to the Boone and Crockett Club rating.

Frankie Laine recorded the song "The Gandy Dancers' Ball" in 1951, but here the Gandy dancers are at a ball for track workers. In 1955 Laine sang the song in the comedy Bring Your Smile Along with a dance ensemble.

In 1962 The Ventures recorded the song "Gandy Dancer", an instrumental composition of their own that appeared on their album Going to the Ventures Dance Party.

The singer and activist Bruce "Utah" Phillips told the lying story in Moose Turd Pie about having worked as a gandy dancer in the American Southwest. Phillips attributed the origin of the workers' shovels to the possibly fabled Gandy Shovel Company in Chicago .

A scene from the 1985 film " The Color Purple " shows a lead singer who instructed his route workers with his call.

In The Adventure Zone's "Dust" arc, Clint McElroy played a character named Gandy Dancer.

In Mazomanie , Wisconsin , is the The Gandy Dancer Festival to honor the Gandy Dancer instead. Held annually on the 3rd Saturday of August, this one-day festival celebrates the hard work the Gandy dancers have done for the United States of America .

See also

Remarks

- ↑ Jelly roll is an old black slang expression for the vulva .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Etymonline.com

- ^ PBS, American Experience, People & Events: Workers of the Central Pacific Railroad. PBS.org , accessed November 23, 2010.

- ^ Railway track and structures. Volume 65, Simmons-Boardman Publishing Corporation , 1969, p. 35.

- ^ William Safire: What's the good word? Times Books, 1982, p. 180.

- ^ Alan A. Jackson: The Railway Dictionary. 4th edition. Sutton Publishing, Stroud 2006, ISBN 0-7509-4218-5 .

- ^ Freeman H. Hubbard: Railroad avenue: great stories and legends of American railroading. Whittlesey House, 1945, p. 344.

- ^ Hobo Terminology. Angelfire.com , accessed November 23, 2010.

- ^ Maggie Holtzberg: The Making of the Film, A diary account of the making of Gandy Dancers. Folkstreams.net , accessed November 23, 2010.

- ^ "The existence of a Gandy Manufacturing Company ... has not been substantiated" Dictionary.com Unabridged Based on the Random House Dictionary, © Random House, 2010 Dictionary.reference.com , accessed November 23, 2010.

- ↑ a b Encyclopediaofalabama.org

- ^ John Lundeen: The advance guide. Volumes 28-29, United Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employees and Railway Shop Laborers, 1919, p. 88.

- ↑ George P. Reynolds, Susan W. Walker: Foxfire 10: railroad lore, boardinghouses, Depression-era Appalachia, chair making, whirligigs, snakes canes, and gourd art. Random House, 1993, p. 31.

- ^ ET Howson; American Railway Engineering Association: Maintenance of way cyclopedia: a reference book covering definitions, descriptions, illustrations, and methods of use of the materials, equipment, and devices employed in the maintenance of the tracks, bridges, buildings, water stations, signals, and other fixed properties of railways. Simmons-Boardman Publishing, 1921, pp. 20-21, 30-31, 141, 147-148, 609, 708.

- ^ The African-American Railroad Experience | KPBS.org

- ↑ a b Robert W. Bruere: The Industrial Workers of the World, An Interpretation. In: Harper's magazine. Volume 137 Making of America Project Harper & Brothers, 1918.

- ^ The Columbus Free Press - Reflections on Black History

- ^ Jean G. Wash, "When Women from Coaldale were Railroad" Gandy Dancers . " In: The Valley Gazette. November 1988, Retrieved July 13, 2015.

- ↑ World Wide Words: Gandy dancer

- ^ The Outlook - Francis Rufus Bellamy - Google Boeken

- ↑ a b c Folkstreams.net

- ↑ a b Arts.state.al.us Archived 2012-03-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Memory.loc.gov

- ^ In the Country of Country

- ↑ web.archive.org

- ↑ Folkstreams.net

- ↑ Folkstreams.net

- ↑ Youtube.com

- ^ Erin Christine Moore: Between Logos and Eros: New Orleans' Confrontation with Modernity . 2008, p. 56.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Alabama: Gandy Dancer Work Song Tradition

- ↑ a b "Calling Track and Military Cadence Calls" . Keepers of Tradition. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- ↑ Gandy Dancer State Trail Archived 2011-08-26 in the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Jordan Buck Heritage Hike" . Burnett County, Wisconsin . Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ↑ LyricsZoo, "Moose Turd Pie," Utah Phillips lyrics, Lyricszoo.com , accessed November 23, 2011.

Web links

- Calling Track and Military Cadence Calls: How an African American Tradition Influenced Military Basic Training

- Vintage Gandy Dancer Video

- Memory.loc.gov John and Ruby Lomax 1939 recordings

- Phillips, Bruce. " Moose Turd Pie " (Lyrics). Retrieved on 2010-11-13.

- " Negro Work Songs and Calls " Library of Congress

- History of The James Jordan Buck

- Music history and information about work.

- Notes on the origin of the term .

- African-American workers songs

- Ribbons of Rail - Maintaining modern American railroads - Washington Post article