HMS Furious (1916)

|

|

|

|---|---|

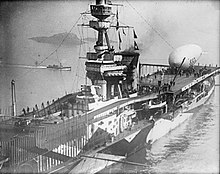

The Furious after reconstruction in 1917 (viewed from port aft) |

|

| Overview | |

| Builder: | Armstrong Whitworth , Elswick |

| Keel laying: | June 8, 1915 |

| Launch: | August 15, 1916 |

| Completion: | July 26, 1917 |

| Technical data according to plan as a large light cruiser |

|

| Displacement: | Construction: 19,825 t Maximum: 23,256 t |

| Length: | between the perpendiculars: 228.6 m over all: 239.8 m |

| Width: | 26.8 m |

| Draft: | 7.3 m |

| Speed: | 32 kn |

| Crew: | 880 men |

| Drive: |

|

| Bunker amount: | 750 t oil normal 3160 t oil maximum |

| Range: | 6000 nautical miles at 20 knots |

| Armament: | Cannons:

Torpedoes:

|

| Armor: | see text |

The HMS Furious ( German angry ) was a warship of the Royal Navy . She was very similar to the ships of the Courageous class and is classified by some authors in this class.

The HMS Furious was designed as a "large light cruiser " during the First World War and converted into an aircraft carrier in several steps . It was used in both world wars and was broken up after World War II .

Design and construction features

The original design of this “Great Light Cruiser” largely corresponded to that of the Courageous class (see there ). The planned displacement and the dimensions were slightly larger. The Furious armor scheme was also identical to that of the Courageous class. The drive system was similar, except that Brown Curtis geared turbines with a slightly higher power were installed. The main difference lay in the armament: the Furious was to carry a 45.7 cm (18 inch ) L / 40 gun in front and aft (rear) each in single turrets, which had an armor of 127 to 229 mm. As means artillery eleven 14-cm-L / 50-guns were provided.

In its original form, the Furious, like her half-sister ships, was viewed as a faulty design. However, with only two instead of four heavy guns, it would have been even less capable of effectively fighting naval targets. Nevertheless, the Furious held the record for the largest caliber used on ships until the appearance of the Japanese battleship Yamato and its sister ship Musashi .

First modifications

The Battle of Skagerrak on May 31, 1916 had shown the value of aircraft-carrying ships to the Royal Navy. However, there was a lack of ships that were fast enough to keep up with the battle fleet. In May 1917, before its completion, the Furious was given a 21 m × 11.8 m hangar for eight to ten seaplanes instead of the front tower and the barbette . Only two 7.6 cm flak were installed, otherwise the gun armament remained as planned.

Above the hangar there was a 69 m × 15.5 m flight deck, which was only intended for take-offs. The starting deck was connected to the hangar below via a hatch. For take-off, the seaplanes were to be placed on a launch vehicle that ran on rails. The aircraft were to land on the water, from where they were to be taken back on board with a crane.

On August 2, 1917, Squadron Commander Edwin Dunning managed the first landing of a wheeled aircraft on a moving warship with a Sopwith Pup on the flight deck of the Furious . To do this, he had to fly around the ship's chimney and navigating bridge, as these blocked the direct approach from behind. The Furious ran full speed against the wind, so that the relative speed of the Pup compared to the flight deck was low and the deck crews practically plucked the aircraft out of the air using ropes attached to it. The third such attempt on August 7, 1917 failed, and Dunning drowned when the plane crashed. Squadron Commander Moore made the last such attempt on September 11, 1917 with a Sopwith Camel . He too shot over the landing deck and fell into the sea, but was able to save himself.

In a further renovation from November 1917 to March 1918, the aft gun turret was also removed and replaced by a hangar with a 86.4 m × 21.3 m landing deck and an elevator. Tests had shown that the Furious's hull was too small for the recoil of such a heavy gun. On this occasion the middle artillery was reduced to ten tubes.

The new flight deck reached up to the chimney and the bridge in the middle of the ship, which separated the front and rear flight deck. Rails ran around the bridge and chimney on both sides, on which the aircraft that had landed were transported back to the front take-off deck. The Furious was supposed to carry 16 wheeled aircraft in this form, but there were up to 26 on board.

In this form, the Furious took part in the attack on the German airship hangars in Tondern (today Tønder) on July 19, 1918, in which the airships L 54 and L 60 were destroyed.

Of the three original 45.7 cm guns, two were installed in the Lord Clive and General Wolfe monitors of the Dover Patrol and used for land target fire at the front in Flanders. With an elevation of 45 degrees, the guns could shoot a 1507 kg projectile over 36 km.

Further modifications to a real aircraft carrier

| Final form as an aircraft carrier | |

|---|---|

| Displacement: | Standard: 22,809 t Use: 28,960 t |

| Length: | as in front of the flight deck: 176 m |

| Width: | as in front of the flight deck: 32.7 m |

| Draft: | 7.6 m |

| Sea speed: | 29.5 |

| Crew: | 1200 men |

| Drive: |

|

| Bunker amount: | 4080 t of oil maximum |

| Range: | 3200 nautical miles at? node |

| Armament: | Cannons:

Planes: 33 |

| Armor: | as before; from 1938: 25 mm on the flight deck |

It had been shown that the superstructures amidships and the exhaust gases from the funnel led to turbulence that made landing on the aft flight deck practically impossible. During the tests on the aft landing deck, fatal accidents occurred on August 7, 1918, when two aircraft crashed into the superstructure on landing. The Furious was therefore converted from June 1922 to August 1925 into a real aircraft carrier with a continuous flight deck. Underneath was a two-story hangar, each 4.6 m high. The upper hangar opened onto the still existing forward flight deck with a length of now 40 m. Fighter planes should take off directly from the hangar via this. Two elevators connected the hangars and flight deck.

The 14-cm guns were partially arranged differently, the 7.6-cm guns were replaced by three 10.2-cm flak. The retention of the sea target artillery corresponded to the tactical ideas of the time: The Furious was fast enough to operate in the reconnaissance screen of the battle fleet. There it was most likely to encounter enemy reconnaissance cruisers that could be effectively combated with a medium-caliber gun.

The Furious was not given a lateral command post (island), but a command post for the ship's command on the right side under the front end of the flight deck and a flight control post on the left. In between there was a retractable navigation stand in the flight deck. The boiler exhaust gases were led through horizontal flue gas ducts on both sides of the upper hangar to the stern of the ship and discharged there. The design without superstructures above the flight deck corresponded to the ideas of the “naval aviation” faction in the British Navy, who rejected superstructures as a hindrance to flight operations.

The emission of exhaust gases at the stern led to turbulence, especially in the approach path - a problem that the aircraft carrier had until the end of its service life. In addition, the flue gas ducts became so hot at high speeds that it was hardly possible to stay near them, and they took up space in the ship's hull. Breyer blames this fact for the fact that the Furious could hold fewer aircraft than the similar conversions of the Courageous class. According to Jordan, the space could otherwise have been used for workshops or crew quarters, but the lower aircraft capacity is due to the space requirements of the 14 cm guns on both sides of the lower hangar.

In 1930 the Furious was given a retractable command post and two of the new 4 cm octets were installed. During the last major renovation from November 1938 to May 1939, the Furious received a small permanent island on the starboard side of the flight deck (right). All 14 cm and 10.2 cm guns were removed and replaced by twelve 10.2 cm flak in twin turrets, and two more 4 cm octets were installed. The flight deck received 25 mm armor. The guns were partially set up on the former front flight deck, which was no longer usable. However, the aircraft on board had become so big and heavy that the front flight deck had become too small for their take-offs anyway.

Mission history

First World War

On July 19, 1918, seven Sopwith Camel aircraft took off from the Furious to attack the German airship hangars in Tondern (now Tønder). Each plane carried two 23 kg bombs. The airships L 54 and L 60 and their hangars were destroyed in the attack. None of the attackers landed on the Furious again . Three of the planes splashed down near the carrier, three were interned in Denmark and one went missing.

Interwar period

In 1919, as part of the intervention of the Western powers in Russia , the Furious was involved in the blockade of Kronstadt .

Second World War

The Furious was used extensively during World War II, mainly off Norway and in the Mediterranean.

On October 8, 1939, she was involved in an attempt to intercept the German battleship Scharnhorst . In April 1940 she operated with the British fleet off Norway. When she arrived off Norway on April 9, 1940, she had no planes on board, they had to be flown in first. On April 11, 18 of their Fairey Swordfish machines attacked Trondheim without result . On April 13, she took part in the second battle in Narvik , eight days later she delivered aircraft for the Allied landing in Narvik.

After that, laid Furious into the Mediterranean, where it mainly due to the transfer of Hawker Hurricane - fighter planes to the besieged Malta was involved. The hurricane took off from the aircraft carriers and landed on Malta. In September 1940 the first such mission took place together with the HMS Argus . From May 1941 to June 1941 she carried out three more operations with the HMS Ark Royal : on May 21, 1941 (Operation Splice, a total of 48 hurricans transferred), on June 6, 1941 (Operation Rocket, a total of 35 hurricans) and on May 29, 1941. June 1941 (due to a takeoff accident, the Furious could only start one machine).

In July 1941, the Furious was meanwhile in northern European waters. Together with the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious , two cruisers and six destroyers, it belonged to an association whose planes were to attack Kirkenes ( Victorious ) and Petsamo ( Furious ). The attack by nine Fairey Albacore bombers, nine Swordfish bombers and six Fairey Fulmar fighter planes of the Furious on the port of Petsamo caused little damage, two planes were shot down.

The carrier was then used again in the Mediterranean. On September 8, 1941, she again transferred a total of 55 hurricans to Malta together with the Ark Royal in Operation Status.

From October 1941 to April 1942, the Furious was converted in Philadelphia and then went back to the Mediterranean. In August 1942, 38 Supermarine Spitfires took off for Malta as part of Operation Pedestal , followed by another 63 Spitfires in two further operations in August (Operation Baritone on August 17, 1942 and Operation Train on October 24, 1942). In November 1942 she supported the landing of the Allies in North Africa near Algiers.

From 1943 she was involved in Home Fleet attacks on Norway. In March 1944, she and the Victorious prepared for an attack on the Tirpitz in the Norwegian Altafjord at Loch Eriboll ( Caithness ) in Scotland . On April 3, 1944, the first successful attack ( Operation Tungsten ) took place, with 19 Fairey Barracuda bombers taking off from the Furious . By June 1944 she was involved in three less successful attacks.

Whereabouts

Worn out by the missions in two world wars, she joined the reserve fleet on September 15, 1944 and was used as a test and target ship for exercises with live airborne weapons in Loch Striven from May 1945 . From 1948 to 1954 it was partly scrapped in Dalmuir and then finally in Troon .

literature

- Siegfried Breyer: aircraft carrier. 1917-1939 . Podzun-Pallas, Wölfersheim-Berstadt 1993, ISBN 3-7909-0484-8 ( Marine-Arsenal . Volume 7: special issue).

- Klaus Gröbig, Uwe Greve: “Furious” aircraft carrier. A ship with many changes . Stade, Kiel 2004 ( Ships, People, Fates . Issue 121).

- Jane's Battleships of the 20th Century . HarperCollins Publishers, London 1996, ISBN 0-00-470997-7 .

- Hans-Joachim Mau, Charles E. Scurell: Aircraft carrier - carrier aircraft . Licensed edition for Bechtermünz Verlag by Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1996, ISBN 3-86047-122-8 .

- Clark C. Reynolds: Aircraft Carriers in WWI and WWII . Gondrom-Verlag, Bindlach 2002, ISBN 3-8112-1948-0 .

Web links

Footnotes

- ^ Jordan, John: Warships after Washington. Seaforth Publishing, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84832-117-5 , p. 161.

- ^ Jordan, John: Warships after Washington. Seaforth Publishing, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84832-117-5 , pp. 6, 156.

- ^ Jordan, John: Warships after Washington. Seaforth Publishing, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84832-117-5 , p. 160.

- ^ Jordan, John: Warships after Washington. Seaforth Publishing, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84832-117-5 , p. 157.

- ^ Breyer, Siegfried: Battleships and battle cruisers 1905-1790. Licensed edition for Manfred Pawlak Verlagsgesellschaft mbH (JF Lehmanns Verlag), 1970, ISBN 3-88199-474-2 , p. 188.

- ^ Jordan, John: Warships after Washington. Seaforth Publishing, 2011, ISBN 978-1-84832-117-5 , p. 163.

- ↑ Mau, Scurell: aircraft carrier - carrier aircraft. 1996, p. 34 f.

- ↑ Reynolds: Aircraft carriers in the 1st and 2nd World War. 2002, p. 28 f.

- ↑ Mau, Scurell: aircraft carrier - carrier aircraft. 1996, p. 51.

- ^ Robert Jackson: The Royal Navy in World War II. Airlife Publishing, Shrewsbury (United Kingdom) 1997, ISBN 1-85310-714-X , p. 14 f.

- ^ Robert Jackson: The Royal Navy in World War II. Airlife Publishing, Shrewsbury (United Kingdom) 1997, ISBN 1-85310-714-X , p. 23.

- ^ Robert Jackson: The Royal Navy in World War II. Airlife Publishing, Shrewsbury (United Kingdom) 1997, ISBN 1-85310-714-X , p. 26 f.

- ^ Robert Jackson: The Royal Navy in World War II. Airlife Publishing, Shrewsbury (United Kingdom) 1997, ISBN 1-85310-714-X , p. 82.

- ^ Robert Jackson: The Royal Navy in World War II. Airlife Publishing, Shrewsbury (United Kingdom) 1997, ISBN 1-85310-714-X , p. 96 f.

- ↑ Helmut Pemsel : Sea rule. Bernard & Graefe Verlag, Koblenz 1995, ISBN 3-89350-711-6 , p. 534.

- ^ Robert Jackson: The Royal Navy in World War II. Airlife Publishing, Shrewsbury (United Kingdom) 1997, ISBN 1-85310-714-X , p. 83.

- ↑ a b c d Warships from 1900 to today. Buch und Zeit Verlagsgesellschaft, Cologne 1979, p. 14.

- ^ Robert Jackson: The Royal Navy in World War II. Airlife Publishing, Shrewsbury (United Kingdom) 1997, ISBN 1-85310-714-X , p. 86 f.

- ↑ Helmut Pemsel: Sea rule. Bernard & Graefe Verlag, Koblenz 1995, ISBN 3-89350-711-6 , p. 570.

- ^ Robert Jackson: The Royal Navy in World War II . Airlife Publishing, Shrewsbury (United Kingdom) 1997, ISBN 1-85310-714-X , pp. 139 ff.

- ^ Robert Jackson: The Royal Navy in World War II . Airlife Publishing, Shrewsbury (United Kingdom) 1997, ISBN 1-85310-714-X , pp. 142 f.

- ↑ Mau, Scurell: aircraft carrier - carrier aircraft. 1996, p. 179.

- ^ Breyer: Aircraft carrier. 1917-1939. 1993, p. 5 ff.