Musashi (ship, 1942)

|

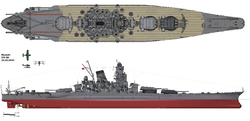

Drawing of the Musashi in October 1944

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

The Japanese battleship Musashi ( Japanese 武 蔵 ) was the second ship of the Yamato- class, one of the two largest, most heavily armed, and most heavily armored battleships ever built. Its heavy artillery , at 46 cm, had the largest caliber of breech loading guns used on ships. It was named after the former Musashi Province . The ship was sunk on October 24, 1944 by air raids by American carrier aircraft.

Construction and construction

The Musashi was 1938-1942 on the Mitsubishi - shipyard in Nagasaki built. The new "super battleship" was named after the old Japanese province of Musashi near Tokyo . All preparations associated with the construction and the construction itself were shielded from the public by extensive secrecy measures. The shipyard was completely enclosed from the outside by a privacy screen made of hemp rope mats. Units of the Kempeitai guarded the area, checked the background of the employees and kept the residents away from elevated places in the area from which one could have seen the facilities.

The launch took place on November 1, 1940, a day that had been selected because of the particularly high water level caused by strong tidal forces . The civilian population of the neighboring settlements had been kept out of the area by an air raid exercise.

The launch was fraught with problems, as the ship was built on a slipway and not, like the Yamato , in a dock . The sliding of the large hull on its way into the water had to be artificially slowed down so that it did not run onto a sandbank on the other side of the harbor basin . Despite this measure, the immersion in the harbor basin triggered a 1.20 meter high tidal wave. The commissioning finally took place after the completion of the final equipment on August 5, 1942.

An external distinguishing feature to the Yamato was the arrangement of the walkways for the crew on the aft deck. While these linoleum- paved paths on the Yamato were angled (parallel to the aircraft tracks ), they were arranged on the Musashi parallel to the ship's axis.

Conversions and retrofits

In July 1943, the Musashi received two Type 22 radar sensors on both sides of the bridge structure. The system was based on magnetron technology, had a range of around 15 miles for the detection of surface targets and worked with a wavelength of 10 cm. It was used for surface search and fire control.

As with other Japanese ships, after the heavy losses suffered by the Japanese navy in 1942 as a result of air raids in the Battle of Midway , thought was given to ways of increasing the Musashi's anti-aircraft armament and implementing possible improvements at the earliest opportunity.

The plans envisaged the dismantling of two of the four 15.5 cm triple turrets of the middle artillery to make space for additional anti-aircraft guns. On the then free area on deck, two extensions were built on starboard and port side, which were around 2.5 meters high and stretched from the bridge structure along the chimney to the aft range finder. These extensions were dominated by three cylindrical elements on each side, in the middle of which a 12.7 cm twin mount of the Type 89 was to be installed for the air defense. However, this did not happen because the weapons required were not available at the time of the shipyard stay in April 1944. Attachments to the reason was built as a temporary solution 25-mm-L / 60-type 96 - automatic cannon in Drilling carriages. Further 25-mm weapons were placed on pedestals amidships and on deck, so that finally 111 tubes of this type of weapon were mounted on the ship.

The exact number of 25 mm weapons housed in towers and those without protection has not yet been conclusively clarified, as neither meaningful records nor precise photographs have been published. Several theories exist about the exact makeup of the ultimate anti-aircraft armament.

In order to further strengthen the air defense capacity, part of the ammunition for the 46 cm main artillery was replaced by a newly developed type 3 incendiary cluster munition ( 三 式 焼 散 弾 , san-shiki shōsandan ). During this stay in the shipyard, the radar system was revised again; the Type 22 radar was replaced by a new model. On the main mast behind the chimney, two Type 13 systems were also installed to search for aerial targets . These had a longer range than the previous systems and could detect aircraft at distances between 50 and 100 km.

Operations and demise

In the initial phase of the Pacific War, the Musashi was not used offensively, but acted as a command ship for various operations and had little contact with the enemy.

In May 1943, the Musashi transported the ashes of the slain Admiral Yamamoto from Truk to Japan. On March 19, 1944, the super battleship was hit by a torpedo from the American submarine Tunny . The damage done did not endanger the battleship, but 18 crew members were killed and the damage had to be repaired in Japan. At the same time, the air defense was converted during the shipyard stay in April 1944.

The ship took part in the battle in the Philippine Sea in June 1944 as remote security for the aircraft carrier combat group and had no contact with the enemy.

She was assigned to the Japanese 1st Battleship Division in October 1944, which was to take part in Operation Sho-I-Go , a plan of attack that eventually led to the Battle of Leyte Gulf .

In the Battle of Leyte, the Musashi, together with her sister ship Yamato and the battleships Kongo , Haruna and Nagato, formed the core of the central combat group that was supposed to destroy the American dropships in order to prevent the conquest of the Japanese-occupied Philippines. The Japanese naval association had left Brunei and had made preparations for the planned breakthrough of the American reconnaissance belt at night by applying a mixture of water and soot to the decks of the ships , which was supposed to act as a camouflage paint.

On the morning of October 23, the fleet was attacked by American submarines. The Dace sank the cruiser Maya . The destroyer Akishimo rescued 769 Maya sailors and handed them over to the Musashi . The association passed the island of Mindoro and ran north-east.

On the morning of October 24, Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita's task force reached the Sibuyan Sea , where it was the target of massive air strikes by American carrier aircraft. The planes of the American Task Groups 38.2, 38.3 and 38.4 attacked in waves that were composed of individual groups which, largely uncoordinated among themselves, sought their goals independently. The exact number of attacks varies depending on the historians' point of view, so that four waves, each of which took off from their aircraft carriers at the same time, became up to six individual attacks, as the groups attacked at a slight time.

The Musashi ran 2,000 meters to starboard, astern of the Yamato , which formed the core of the Japanese formation. The circular formation was protected from the outside by a ring of destroyers.

At 10:00 a.m. the Musashi's radar recorded the first groups of American fighter planes approaching the formation from the east. The Americans sent around 50 Grumman TBF Avenger , Curtiss SB2C Helldiver and Grumman F6F Hellcat aircraft in this first wave.

The first attack began at 10:26 a.m. by dive bombers from the Intrepid and Cabot . The mass of attacking SB2C bombers released their 227 kg bombs from a height of 600 meters. That was not enough to penetrate the armored citadel inside the ship or the armor of the main turrets. Tower A was hit directly, but the bomb ricocheted off the turret armor and fell into the sea. Four bombs exploded right next to the ship and loosened some riveted connections on the hull. The crews of the torpedo bombers, on the other hand, attacked diagonally from the front in small groups, if possible from both sides at the same time, in order to increase the probability of their weapons being hit.

A group of approaching torpedo bombers was detected too late and an Avenger bomber's torpedo hit starboard amidships. Due to the loosened rivet connections at this point, the damage caused by the 300 kg of Torpex explosives in the torpedo was relatively great, and water penetrated the battleship. This resulted in a list of 5 °. It could be reduced by the bilge pumps . Among the crews who operated the unprotected anti-aircraft weapons, there had already been dead and wounded from bomb fragments and machine gun fire; the speed of the ship could be kept at 24 knots.

The second attack took place at 12:45 p.m. by 42 aircraft from the same aircraft carriers that had already started the aircraft of the first wave. Two plane bombs hit the Musashi . One penetrated the upper deck and exploded in an anti-aircraft ammunition chamber below the heavy anti-aircraft guns. The fragments from this bomb damaged a steam pipe in engine room 2 below, so that it had to be evacuated. As a result, the inboard port propeller stopped and the speed dropped to 22 knots. In addition, three more torpedoes hit the battleship. In particular, the bomb hits killed many crew members between the upper deck and armored deck, in the ammunition chamber and in a crew quarters. A third of the anti-aircraft crews had already dropped out due to death or injury at this point. At 12:53 p.m., the attack by the second group of aircraft from the second attack wave began. Four torpedoes and four aerial bombs hit the ship. Two torpedoes exploded again in the foredeck, so that finally the majority of the hull in front of the armored citadel, which protected the vital ship systems in the hull and reached up to tower A, was flooded. The draft of the bow increased by a further two meters. A torpedo hit on starboard amidships at frame 138 led to a new water ingress. An aerial bomb hit the upper deck at frame 138 and destroyed several 25 mm anti-aircraft guns. The list was finally stabilized to 1–2 ° starboard by counter-flooding.

The losses in light anti-aircraft weapons were very heavy, only 25% of the weapons were still operational, the rest failed due to the destruction or death of the operating crew. The ranks of the anti-aircraft crews were replenished by the sailors previously taken over from the sunken cruiser Maya .

The speed fell to below 20 knots, also due to the increased water resistance, and the Musashi could no longer follow the fleet and turned back. The fleet association subsequently changed course several times, which brought him back within sight of the heavily damaged Musashi several times , the last time around 6:00 p.m.

During the third attack by around 70 aircraft from 1.30 p.m., the Musashi received two more torpedo hits on starboard and one on port. The attacking aircraft had taken off from the carriers Essex and Lexington . An aerial bomb penetrated the deck above the bow and exploded in the forward infirmary. Much of the medical staff and the wounded were killed. The most critical water ingress was also in the forecastle, where two torpedoes exploded immediately in front of the torpedo bulge , causing particularly severe damage. Several large storage rooms in this area overflowed. The draft at the bow increased another two meters.

A final wave of attacks of about 100 aircraft, launched by the carriers Enterprise , Franklin and again by the Intrepid and the Cabot , arrived between 2:10 and 2:45 p.m. Without the protective anti-aircraft fire of the fleet association and with slow speed, the battleship was an easy target and was hit by ten bombs and eleven torpedoes. The majority of the torpedoes hit the port side. Other air defense crews died, a bomb destroyed part of the bridge and killed 78 sailors, including the navigational officer, the chief air defense officer and wounded Captain Inoguchi. The forecastle sank further due to ingress of water, so that it was already washed over by waves; the list reached 10 ° to port. It was initially able to be reduced to 6 ° by counter-flooding.

The attempt to steer the Musashi to the nearby coast of the Bondoc Peninsula and to land there or even to bring her to the port of San José on the island of Mindoro failed when the generator rooms were flooded and the electricity in the ship went out . The forecastle was now so deep in the water that any possibility of maneuvering the ship had been lost. The attempt to compensate for the port list by shifting equipment and crew to starboard and flooding one of the engine rooms to starboard failed.

At 19:20, the commander finally gave the order to abandon the ship. The list had risen again and worsened within 15 minutes from 18 ° to 30 ° port. After the flag had been brought down and the imperial portrait had been recovered, the order was given to disembark. Captain Inoguchi stayed on the ship. Before the entire crew could leave the ship, the Musashi began to sink over the bow to port. Two of their four propellers were still turning when the stern rose almost vertically out of the water shortly before sinking. There were further losses when seamen jumped from the high stern into the sea 40 meters below and fatally injured themselves on the propellers. Shortly after the ship sank, one, according to other witnesses two, serious underwater explosions occurred at the place of the sinking.

The destroyers Kiyoshimo and Shimakaze ultimately rescued 1,376 Musashi sailors during the night . 1023 crew members were killed. 143 of the Maya survivors also died in the sinking of the Musashi . Several hundred of the rescued sailors were later incorporated into the Japanese army in the Philippines, most of them perished in the 1945 Battle of Manila .

Work-up

- Looking back, some experts reproach the ship's command. Mistakes were made in combating the damage and opportunities remained unused to increase the ship's buoyancy in the last half of the battle by pumping out the spaces previously filled with water for counter-flooding. However, the many failures of the ship's security teams, the partly destroyed pumping equipment and the difficult communication in the last phase of the battle make it difficult to assess whether this would have been possible.

- The Musashi anti-aircraft defenses that day were consistently rated as ineffective. The 12.7 cm guns fired time-fused grenades to create a barrage with the explosions at fixed heights. However, this technology was ineffective against the small, agile carrier aircraft. The light 25 mm weapons, on the other hand, had too short a range, too low cadence and their defensive effect is considered inadequate. The Musashi fired several volleys of incendiary cluster munitions with its 46 cm guns on the enemy aircraft, but was unsuccessful.

- The exact number of torpedoes the Musashi hit on October 24th varies between 19 and 26, depending on the source. Ultimately, however, there is agreement that the damage caused by the torpedo hits - 17 full bombs and 18 close hits - is each Had made the ship a certain total loss. Even when reaching a port, repairing the Musashi would not have been enough; the battleship would have practically had to be rebuilt. The large number of torpedoes that were necessary for the sinking led the American planners to the realization that future torpedo attacks on large ships should only be carried out from one side in order to capsize the ships through one-sided water inrush .

- The fact that on October 24th the Musashi attracted the bulk of the air raids and remained the only sunk ship of the Japanese main force in these attacks, combined with wrong decisions by the American leadership, probably contributed decisively to Admiral Kurita's combat group at The next day could emerge largely intact in front of Samar to attack the security forces of the invasion fleet.

wreck

The last known location of Musashi was approximately 13 ° 7 ' N , 122 ° 32' O .

On March 2, 2015, Paul Allen announced on Twitter that the wreck of the Musashi had been found at a depth of around 1,100 meters in the Sibuyan Sea. Allen used his yacht Octopus and the associated diving equipment after Musashi to search. After the discovery of the wreck, he published pictures and videos that show the upright bow, the bridge tower lying on its side and the stern lying keel up. The completely destroyed midships area of the wreck indicates explosions of the ammunition stores below the main guns during the sinking.

Evidence and references

literature

Technical literature by Japanese authors on Yamato / Musashi

- Todaka Kazushige: The Battleship YAMATO and MUSASHI. Kure Maritime Museum, Supplemental Volume, Kure 2005.

- Chihaya Masatake: IJN YAMATO and MUSASHI Battleships. Warship Profile Vol. 30, Windsor 1973.

- Maru Special: Japanese Naval Vessels, Vol. 52, Yamato / Musashi. Maruzen, Tokyo 1981.

- Maru Special: Japanese Naval Vessels, Second Series Vol. 115, History of YAMATO-Class. Maruzen, Tokyo 1986.

- Maru Special: The Imperial Japanese Navy, Vol. 1 (Battleships I). Maruzen, Tokyo 1989 (2nd edition 1994).

- Gakken Pictorial Series Vol. 50: Bird's Eye YAMATO. Gakken, Tokyo 2005.

- Fukui Shizuo: Japanese Naval Vessels Illustrated, 1869-1945, Vol. 1 Battleships and Battlecruisers. KK Publishers, Tokyo 1974. (2nd edition 1982).

- Ishiwata Kohji: Yamato Class, in: Japanese Battleships, Ships of the World Vol. 391. Kaijinsha, Tokyo 1988, p. 130-143.

- Watanabe Yoshiyuki: Japanese Battleships. Gakken, Tokyo 2004.

- Model Art Vol. 6: Drawings of Imperial Japanese Naval Vessels Vol. 1 (Battleships and Destroyers). Tokyo 1989 (2nd edition 1995).

Selected non-Japanese sources on Yamato / Musashi

- Janusz Skulski: The Battleship YAMATO. Conway, London 1988 (3rd edition 2000).

- Steve Wiper: Yamato Class Battleships. Warship Pictorial Vol. 25, Tucson 2004.

Web links

- Chronology of the history of Musashi (English)

- Illustrated analysis of various theories on anti-aircraft armament of the Musashi (Japanese)

- Finding the Musashi on paulallen.com (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Akira Yoshimura: Battleship Musashi: the making and sinking of the world's biggest battleship. Kodansha, 1999, ISBN 4-7700-2400-2 , p. 116.

- ↑ a b Yasuzō Nakagawa: Japanese Radar and Related Weapons of World War II. Aegean Park Press, 1998, ISBN 0-89412-271-1 .

- ^ Barrett Tillman: Helldiver Units of World War 2. Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-85532-689-2 , pp. 45, 46, 47.

- ^ Barrett Tillman: Avenger units of World War 2. Osprey Publishing, 1999, ISBN 1-85532-902-6 , pp. 86, 37, 38.

- ^ William H. Garzke: Battleships: axis and neutral battleships in World War II. US Naval Institute Press, 1985, ISBN 0-87021-101-3 , p. 70.

- ^ David C. Evans: Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887-1941. US Naval Institute Press, 2003, ISBN 0-87021-192-7 , pp. 382, 379.

- ↑ a b http://www.combinedfleet.com/Musashi.htm Combined Fleet.com, viewed April 24, 2010

- ^ HP Willmott: The battle of Leyte Gulf: the last fleet action. Indiana University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-253-34528-6 , pp. 115, 116.

- ^ HP Willmott: The battle of Leyte Gulf: the last fleet action. Indiana University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-253-34528-6 , pp. 113ff.

- ↑ Paul Allen Twitter: https://twitter.com/PaulGAllen/status/572431062522982400

- ^ Finding the Musashi Paul Allen, March 4, 2015, viewed January 23, 2017