Hu Zhengyan

Hu Zhengyan ( Chinese 胡正 言 , Pinyin Hú Zhèngyán , W.-G. Hu Cheng-yen ; also: Hu Yuecong; * around 1584, or: 1582, 1580; died 1674) was a Chinese painter, die cutter and editor. He is known as the Master of the Ten Bamboo Hall . He calligraphed and designed pictures and cut seals . His literary works were mainly editions of other works, but in some cases also records of his own work.

Hu lived in Nanjing in the transition period from the end of the Ming Dynasty to the beginning of the Qing Dynasty . As a Ming loyalist, he was offered an official post in the rump government of the Prince of Fu's Hongguang reign . However, he refused and was content with a small, insignificant official post. However, he designed the seal of the Hongguang Emperor and was so loyal to the dynasty that he largely withdrew from society after the regent was captured and died in 1645. In his learned publishing house, the Ten Bamboo Hall , he used various Chinese printing techniques and embossing processes . His refined printing processes were pioneering achievements.

His best-known work is the catalog Das Manual des Zehn-Bambus-Studios for Painting and Calligraphy , an art textbook that was considered a standard work for two hundred years and has been reprinted. He also published Siegel catalogs, scholarly and medical texts, volumes of poetry and artistic writing paper. He often put his own foreword in front of these books, or had one of his brothers write a foreword.

Life

Hu was born in 1584 (or early 1585) in the Xiuning Area , Anhui . Both his father and his older brother Hu Zhengxin ( Chinese 正心 , stage name Wusuo, Chinese 無所 ) were doctors and from the age of 30 he went on trips with you when they were traveling doctors through the areas around Lu'an and Huoshan moved. It is generally believed that Zhengyan also practiced medicine himself, although the earliest sources on this date from the second half of the 19th century.

In 1619 Hu found himself in Nanjing, where he lived with his wife Wu . Their home on Jilongshan ( Chinese 雞籠 山 , today: Beiji Ge ), a hill on the northern city wall , was a meeting place for many like-minded artists. Hu named it the Ten Bamboo Hall or Studio ( Shizhuzhai , Chinese 十 竹 齋 ) after ten bamboo trees that grew in front of the building. The property served as the headquarters for his printing business, where he employed ten artists, including his two brothers Hu Zhengxin (Wusuo) and Hu Zhengxing ( Chinese 正 行 , (Zizhu, Chinese 子 著 )) and his sons Hu Qipu ( Chinese 其 樸 ) and Hu Qiyi ( Chinese 其 毅 , K : Chinese 致 果 Zhì guǒ).

During Hu's lifetime, the Ming dynasty , which had ruled China for over 250 years, was destroyed and replaced by China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing dynasty . After the fall of the capital Beijing in 1644, the remnants of the Ming imperial family and some ministers established a loyal Ming regime in Nanjing with Zhu Yousong as the Hongguang emperor. Hu, who for his artistry in the seal-carving and its capabilities in the field of seal script known , was created a label for the new emperor. The court offered him the position of court clerk (zhongshu sheren, Chinese 中 書 舍人 ), but he did not accept the post, although in later personal seals he sometimes carried the title zhongshu sheren .

According to Wen Ruilins ( Chinese 温 睿 臨 ) Nanjiang Yishi ( Chinese 南疆 繹 史 "Lost History of the South"), Hu studied before the conquest of Nanjing by the Qing at the Imperial College in Nanjing and at the same time held a position in the Ministry of Rites , where he was official Recorded proclamations; he created the Qin Ban Xiaoxue ( Chinese 御 頒 小學 "Imperial Promotion of Minor Teaching") and the Biaozhong Ji ( Chinese 表 忠 記 "Record of Loyalty on Display"). He was promoted to the Ministry of Personnel and was also admitted to the Hanlin Academy , but before he could take that position, Nanjing was conquered by the Manchu (Qing). Since contemporary biographies do not report these events (Wen's works were not published until 1830), it is assumed that they were only invented afterwards.

Hu retired from public life in 1646. Xiao Yuncong and Lü Liuliang report that they visited him when he was his age (1667 and 1673, respectively). He died in poverty at the age of 90, sometime in late 1673 or early 1674.

Seal cuts

Hu Zhengyan created personal seals for numerous dignitaries. His style was based on the classic Han Dynasty seal script, and he followed the Huizhou seal-tailoring school founded by his contemporary He Zhen . Hu's calligraphy, although balanced and with a clear composition, is more angular and rigid than its classic models. The Huizhou seals imitate ancient, weathered models, although Hu, unlike some colleagues, did not normally use artificial aging processes for the seals.

Hu's work was well known. Zhou Lianggong , a poet who lived in Nanjing around the same time, writes in his biography of seal tailors (Yinren Zhuan, Chinese 印人 傳 ) that Hu makes “miniature stone carvings with ancient seal inscriptions for travelers to wrestle for and for treasures He emphasizes that Hu's seals were also popular with visitors and travelers who stopped in Nanjing.

In 1644 Hu took on the task of making a new imperial seal ( Chinese 傳 國 璽 , Pinyin chuán guó xǐ ) for the Hongguang emperor. He designed the seal after a period of fasting and prayer and presented his work together with an essay, the Great Admonition of the Seal ( Chinese 大 寶 印 , Pinyin Dabao Zhen ), in which he mourned the loss of the Chongzhen Emperor's seal and where he begged Heaven to restore it. Hu was concerned that his essay might go unnoticed because he had not written it in the traditional rhyme form, the pianti ( Chinese 駢 die ) used in the Chinese official examinations , but his essay and seal were nonetheless used by the court of the southern Ming accepted.

The Ten Bamboo Hall

Despite his fame as an artist and seal cutter, Hu was primarily a publisher. His publisher, the Zehn-Bambus-Studio, printed reference works on calligraphy, poetry and art, as well as medical texts, books on etymology and phonetics ; but also copies and comments on the Confucian classics . Unlike contemporary publishers, Ten Bamboo Studio did not publish novels or plays. This focus on academic texts was possibly due to the publisher's location: the building was north of the Nanjing Guozijian (National Academy) in close proximity, which resulted in a sales advantage for academic texts. Between 1627 and 1644, Ten Bamboo Studio published more than twenty prints aimed at a wealthy, educated elite. The earliest publications were medical textbooks ( Tested Prescriptions for Myriad Illnesses ( Chinese 萬 病 驗方 , Pinyin Wanbing Yanfang ), 1631; the book was reprinted ten years later). Hu's brother Zhengxin, who was a medical doctor, may be the author of this book.

During the 1630s, the publisher also printed political works dealing with the laws of the Ming; including the Huang Ming Biaozhong Ji ( Chinese 皇 明 表 忠 紀 , "Imperial Record of the Ming on Loyalty"), a biography of loyal Ming officials, and the Huang Ming Zhaozhi ( Chinese 皇 明 詔 制 , "Edicts of the Imperial Ming") , a list of imperial proclamations. After the fall of the Ming Dynasty, Hu renamed the publisher. He called it the hall that comes from the past ( Chinese 迪 古 堂 , Pinyin Digu tang ). However, the original seal was still used. Despite the withdrawal from society after 1646, the publisher continued to publish books for a long time, but mostly limited to seal impressions and catalogs with Hu's seal cuts.

During the Ming Dynasty, great developments in color printing had been made in China. In his studio, Hu Zhengyan experimented with various methods of wood panel printing and invented processes for color printing and embossing processes . He was the first in China to be able to produce color prints using the douban yinshua process ( Chinese 饾 板 印刷 ; "sorted block prints"). This method used many blocks, each of which was cut with part of the original image and each of which was a different color. It was a lengthy, arduous process that involved cutting forty to fifty printing blocks and doing up to seventy inks and prints to produce a single image. Hu also used a related form of wood panel printing called taoban yinshua , ( Chinese 套板 印刷 "set block printing"). The method had been used since the Yuan Dynasty but only recently came back into fashion. Hu improved the techniques with a method that wiped some of the ink off the pads before they were reprinted. As a result, he achieved a color gradient and color shading modulations that were previously not technically possible.

For some pictures, Hu used a blind embossing technique gonghua ( Chinese 拱 花 , "embossed flowers") or gongban ( Chinese 拱 板 " embossed boards"), in which an uncolored stamp is used to stamp embossings into the paper. He used the technique for white relief effects on clouds and for light effects on water or plants. This technique was a relatively new process invented by Hu's contemporary, Wu Faxiang , who was also based in Nanjing. Wu first used this technique in his print Luoxuan Biangu Jianpu ( Chinese 蘿 軒 變 古 箋 譜 "Wisteria Studio Letter Paper "), which was printed in 1626. Both Hu and Wu used embossing processes to make decorative writing paper, the sale of which generated an additional income for the Ten Bamboo Studio.

Works

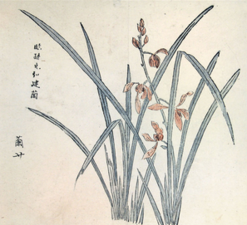

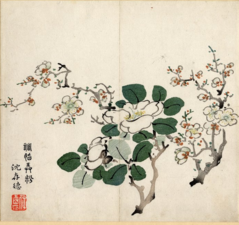

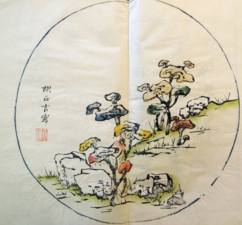

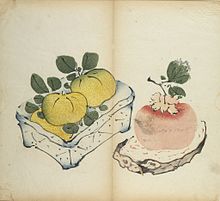

Hu's best-known work is the Shizhuzhai Shuhuapu ( Chinese 十 竹 齋 書畫 譜 , German Ten-Bamboo Hall Manual for Painting and Calligraphy), an anthology of around 320 prints by around thirty different artists (including Hu himself) from 1633 It consists of eight parts, with calligraphy, bamboo , flower, stone, bird and animal, plum, orchid and fruit painting. Some of these parts were published earlier as individual volumes. In addition to the aspect of an art collection, the manual was also intended as an art textbook, with instructions on correct brush holding and technique and several pictures that were intended for beginners to imitate. Although these instructions only appear in the parts on orchids and bamboo, the book remains the first example of a categorical and analytical approach to Chinese painting to this day. In this book, Hu used his various printing methods, which he used to create gradients in the images instead of showing clear outlines and overlaps. The manual is in the traditional " butterfly binding " ( Chinese 蝴蝶 裝 , Pinyin hudie zhuang ), whereby full-page illustrations are folded so that each illustration takes up a double page. This binding allowed the reader to lay the book flat and look at every single picture carefully. The Cambridge University Library published a complete digital scan of the manual in 2015, including all scriptures and illustrations. Said Charles Aylmer , Head of the Cambridge University Chinese Department reports:

"The bond is so fragile and the manual is so filigree that until it was digitized we never had the opportunity to look through it or study it - despite its undoubted importance for scholars."

This book influenced all color printing in China, and paved the way for the later but better known Jieziyuan Huazhuan ( Chinese 芥子 園 畫 傳 "Manual of the Mustard-Seed Garden") and developed its own dynamic in Japan , where it was reprinted and the development of Ukiyo-e with the color wood board printing method of Nishiki-e Japanese 錦 絵 . The popularity of Shizhuzhai Shuhuapu was so enormous that reprints were reprinted throughout the late Qing period .

Hu also published the Shizhuzhai Jianpu ( Chinese 十 竹 齋 箋 譜 "Ten Bamboo Hall Stationery"), a collection of paper samples embossed with the gonghua method. While this work was primarily a catalog of decorative writing papers, it also contained images of stones, people, ritual vessels, and other objects. The book was bound in the baobei zhuang style ( Chinese 包 背 裝 , "wrapped back"), in which the folios are folded, folded and sewn along the open ends. The work was first published in 1644 and was reprinted in four volumes between 1934 and 1941 by Zheng Zhenduo and Lu Xun , and republished in a revised form in 1952.

Further publications

Other works by Hus Verlag were a reprint of Zhou Boqi's manual of the seal script calligraphy Liushu Zheng'e ( Chinese 六 書 正 譌 , "The six styles of calligraphy, correct and incorrect") and the related Shufa Bi Ji ( Chinese 書法 必 稽 , "Necessary studies on calligraphy"), in which common mistakes in the formation of the characters were dealt with. With his brother Zhengxin, Hu published a new edition with introductions to the Confucian classics entitled Sishu Dingben Bianzheng ( Chinese 四 書 定本 辨正 , "The Standardized Text of the Four Classics, Identified and Improved," 1640), which contains the correct arrangement and pronunciation of the text was recorded. A similar approach was followed by the Qianwen Liushu Tongyao ( Chinese 千 文 六 書 統 要 , "Basics of the Thousand-Character Classic in Six Fonts", 1663), which Hu put together with his calligraphy teacher, Li Deng . The work was only published after Li's death, in part as a homage to him.

The three brothers worked together to publish a student manual for poetry by their contemporary Ye Tingxiu , which was simply referred to as Shi Tan ( Chinese 詩 譚 , "Discussion of Poetry", 1635). Another work on poetry was the Leixuan Tang Shi Zhudao Weiji ( Chinese 類 選 唐詩 助 道 微機 , "Helpful Principles on the Subtle Works of Selected Tang Poems "). This book was a compilation of several works on poetry and also contained colophons by Hu Zhengyan himself.

Among the more obscure publications was a text on Chinese dominos Paitong Fuyu ( Chinese 牌 統 浮玉 ), which was written under a pseudonym, but still contained a foreword by Hu Zhengyan.

gallery

- Pictures from the ten-bamboo hall manual for painting and calligraphy

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Suzanne E. Wright: Hu Zhengyan: Fashioning Biography. In: Ars Orientalis. vol. 35: 129-154, The Smithsonian Institution (jstor 25481910); doi: 10.2307 / 25481910 [1] 2008.

- ↑ a b c Sun Shaobin: 十 竹 斋. ( Memento of the original from July 1, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Ten Bamboo Studio) ZhuoKeArts.com June 26, 2015.

- ^ A b c d Lu Yongxiang: A History of Chinese Science and Technology. Springer 2014, ISBN 978-3-662-44166-4 , pp. 205-206.

- ↑ a b c d Jessica Rawson : The British Museum book of Chinese Art. ( Memento of the original from October 20, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. The British Museum Press, London 2007. ISBN 978-0-7141-2446-9

- ↑ Denis Crispin Twitchett, John King Fairbank: The Cambridge History of China: The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644. Part 1 Cambridge University Press 1988, ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2 , p. 642.

- ↑ 温 睿 臨 (Wēn Ruì lín): 南疆 逸史 (Nanjiang Yishi) 崇文 書店 (Chongwen Shudian) 1971: 306-307 (Chinese).

- ↑ a b 杜 濬: 變 雅 堂 遺 集上海 古籍 出版社 1894: 18–20 (Chinese).

- ↑ "creates miniature stone carvings with ancient seal inscriptions for travelers to fight over and treasure" 印人 传.海南 出版社 2000. ISBN 978-7-80645-663-7

- ^ A b Suzanne E. Wright: "Luoxuan biangu jianpu" and "Shizhuzhai jianpu": Two Late-Ming Catalogs of Letter Paper Designs. In: Artibus Asiae. 2003 vol. 63, 1: 69-115. jstor = 3249694

- ↑ Cynthia J. Brokaw, Chow Kai-Wing: Printing and book culture in late Imperial China. University of California Press 2005: 131. ISBN 978-0-520-23126-9

- ↑ 馬孟晶 (Mǎ Mèng Jīng): 晚 明 金陵 "十 竹 齋 書畫 譜" "十 竹 齋 箋 譜" 硏 究 National Taiwan University Dept. of Art History 1993: 29-30. (Chinese)

- ↑ Chow Kai-Wing: Publishing, culture, and power in early modern China. Stanford University Press 2004: 84. ISBN 978-0-8047-3368-7

- ^ Wu Kuang-Ch'ing: Ming Printing and Printers. In: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 1943, vol. 7, 3: 203-210. Harvard-Yenching Institute ( doi: 10.2307 / 2718015 jstor = 2718015)

- ^ The Art of Chinese Traditional Woodblock Printing. Hong Kong Heritage Museum, June 29, 2015. (PDF)

- ↑ Fan Dainian, RS Cohen: Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology. Springer, September 30, 1996, ISBN 978-0-7923-3463-7 , p. 339.

- ^ A b Hu Zhengyan China Culture. ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: China Daily 2003.

- ↑ Guo Hua: Selected Anecdotes about Su Shi and Mi Fu World Digital Library , Chinese Rare Book Collection 1621.

- ^ Robert E. Hegel: Reading Illustrated Fiction in the Late Imperial China. Stanford University Press 1998, ISBN 978-0-8047-3002-0 , p. 197.

- ↑ Applying colors. Gems of the Rare Books from the National Palace Museum's Collections. National Palace Museum.

- ↑ Ding Naifei: Obscene Things: Sexual Politics in Jin Ping Mei. Duke University Press 2002, ISBN 0-8223-2916-6 , p. 54.

- ^ A b Francesca Bray, Vera Dorofeeva-Lichtmann, Georges Métailié: Graphics and Text in the Production of Technical Knowledge in China: The Warp and the Weft. Brill 2007, ISBN 90-04-16063-9 , p. 464.

- ↑ Thomas Ebrey: The Editions, Superstates and States of the Ten Bamboo Studio Collection of Calligraphy and Painting , East Asian Library and Gest Collection, Princeton University 2015. (PDF)

- ↑ Simon Eliot, Jonathan Rose: A Companion to the History of the Book. John Wiley & Sons 2011, ISBN 978-1-4443-5658-8 , p. 107.

- ^ A b c Joseph Needham, Tsien Tsuen-Hsuin: Science and Civilization in China : Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Pt. 1, Paper and Printing. Cambridge University Press 1985, ISBN 978-0-521-08690-5 , p. 286.

- ^ Suzanne Wright: Chinese Decorated Letter Papers. In: Antje Richter: A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture. Brill 2015, ISBN 978-90-04-29212-3 , p. 116.

- ↑ Tsien Tsuen-Hsuin: Book Review: Chinese Color Prints from the Ten Bamboo Studio. In: Journal of Asian Studies. February 1975, vol. 34, 2: p. 514. ( doi: 10.2307 / 2052768 jstor = 2052768)

- ↑ Shi zhu zhai shu hua pu (FH.910.83-98) University of Cambridge Digital Library 2015.

- ↑ "The binding is so fragile, and the manual so delicate, that until it was digitized, we have never been able to let anyone look through it or study it - despite its undoubted importance to scholars." One of World's Oldest Books Printed in Multi-Color Now Opened & Digitized for the First Time. Open Culture, August 17, 2015.

- ^ Kathleen Kuiper: The Culture of China. The Rosen Publishing Group 2010, ISBN 978-1-61530-140-9 , p. 213.

- ↑ James Albert Michener : The Floating World. University of Hawaii Press 1954, ISBN 978-0-8248-0873-0 , p. 88.

- ^ Robert T. Paine Jr .: The Ten Bamboo Studio. In: Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts. December 1950, vol. 48, 274, pp. 72-79. jstor = 4171078

- ^ The East Asian Library Journal. Gest Library of Princeton University 1998, p. 96.

- ↑ Robert H. van Gulik : 中國 古代 房内 考: A Preliminary Survey of Chinese Sex and Society from Ca. 1500 BC Till 1644 AD Brill Archive 1974, ISBN 978-90-04-03917-9 , p. 322.

- ↑ 荣宝斋 与 鲁迅 、 郑振铎: 叁. Rong Bao Zhai and Lu Xun, Zheng Zhenduo: Part 3. ( Memento of the original from March 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. RBZarts.COM

Web links

- Shi zhu zhai shu hua pu (Ten Bamboo Studio collection of calligraphy and painting) , digitized from the Cambridge Digital Library .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hu, Zhengyan |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | 胡正 言; 胡, 正言; 胡 曰 從; 胡 十 竹 (Chinese); Hu Yuecong; Hu Yue cong; Hu Shizhu; Hu Shi zhu; Hu, Chêng-yen; Chêng-yen, Hu; Hu, Cheng-yen; Master of the Ten Bamboo Hall; Hwu Jenq-yan, Ôo Tsiànn-giân, ɦou tsen-nyĩ, Wùh Jing-yìhn, Yüeh-ts'ung |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Chinese politician, scholar, printer and artist of the Ming period |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1584 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Xiuning Area , Anhui |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1674 |

| Place of death | Nanjing , China |