Icelandic sagas

The Icelandic sagas (Íslendingasögur; also: Islandsagas ) are a genre of Icelandic saga literature and materially an area of Norse literature . The Íslendinga sögur include about three dozen larger prose works and a number of Þættir , all of which have been anonymously passed on.

Age and origin

The literary form of the Icelandic saga developed from the heroic poetry of old Germanic heroic songs , as they are passed down in the poems of the Edda song . The origin of Íslendinga sögur from heroic poetry in the various Eddic songs by Sigurðr can be clearly demonstrated : Reginsmál (the song of Regin), Fáfnismál (the song of Fáfnir), Sigurðarkviða in forna (the older Sigurðr song), Sigurðarkviða meiri (the longer Sigurðr song) and Sigurðarkviða in scamma (the short Sigurðr song), but also in Atlakviða (the Atli song), Atlamál in grœnlendsku (the Greenlandic song of Atli) or Hamðismál in forno (the old song of Hamðir) and not in the Codex Regius , but in the Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks konungs , handed down Hlöðskviða (the song of Hlöðr or the Hunnenschlachtlied).

Since no Íslendinga saga has survived in the original manuscript, opinions differ widely as to the age of these sagas. If the hypothetical oral preliminary stages are included, the time of origin disappears in the historical darkness of early Icelandic times. But also for the written versions, the dates of origin and the authorship are not without controversy. A chronology must remain aware of considerable uncertainties. Such a chronology goes back to Sigurður Nordal, which aims at a temporal structure of the Íslendinga sögur:

- 1200 to 1230 (6 sagas);

- 1230 to 1280 (12 sagas);

- 1270 to 1290 (5 sagas);

- around 1300 reworked sagas from older versions (at least 6);

- originated in the 14th century (6 sagas).

Oral versus written form

The Icelandic sagas are works of art that are among the most important literary achievements of medieval Europe. They are an independent, completely independent creation of Icelandic culture . They were created by authors and must therefore be referred to using literary terms such as novel or novella .

The scientists of the so-called Icelandic School , to which Björn M. Ólsen , Sigurður Nordal and Einar Ó. Sveinsson , examined this saga genre as individual works of art, and demanded that they must be examined according to literary-narrative aspects. With this demand they opposed the view that the Íslendinga sögur were based on stories from oral tradition and were only recorded later. Linked to the original orality thesis is the view that it is largely pre-Christian (pagan) literature. Most of the sagas were written between 1150 and 1350 , the Icelandic population had been Christianized for a century and a half, and the authors wrote under the protection of the church, which in Iceland promoted the telling of the sagas. It is mainly clergy who are considered to be the authors of the Íslendinga sögur.

Protagonists and content

The protagonists are Icelanders and the scenes of the sagas are mostly in Iceland; occasionally in Norway , England , Russia , the Baltic States and other Nordic countries. Most of the events described in these sagas occurred between the founding of the Althing in 930 and 1030 AD, when the new state was considered established, and until Christianization around 1030. This period is known as the "saga time". Fantastic elements are hardly included, the descriptions are largely realistic.

The sagas

- tell of the fate of a family ( ættarsögur ; family saga, genealogical chronicle);

- put the biography of a single protagonist at the center of the narrative (especially the Skaldensagas);

- describe genealogies and events associated with them in a larger region and across generations.

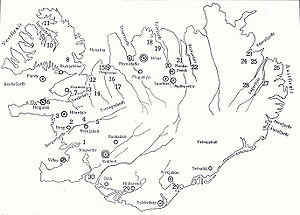

Often the Íslendinga sögur are geographically classified into different groups according to their main location:

- Borgarfjörður (Bgfj.);

- West Iceland, v. a. the region around the Breiðafjörður (W);

- Northwest Peninsula, v. a. Vestfirðir (vf.);

- western north country, v. a. Húnavatnsþing (N [w]);

- eastern north country, v. a. Eyjaförður (N [ö]);

- East Iceland, v. a. Austfirdir (O);

- South Iceland (S).

This classification made use of the observation that sagas from individual areas have certain similarities. At the same time, such a structure also shows how differently the sagas are distributed across the individual parts of Iceland , how widespread they were and how great their acceptance was among the population.

Differentiation from the legend

The legend in the ecclesiastical sense aims to show a historical person who leads a religiously exemplary lifestyle. To this end, the legend reshapes the continuum of the story and the individual lives of its protagonists into a chain of events. The life of a person as a legend of saints points to a world beyond. This is precisely what the saga does not do, rather it tells a realistic story in which the determinants of place, time and social environment (especially family), already mentioned above, represent important aspects.

Stylistic features

Although direct speech in the Íslendinga sögur is the most important stylistic device, the proportion can vary considerably from saga to saga. The number of protagonists also differs considerably; it can range from a dozen in the Hrafnkels saga to up to 600 in the Njáls saga .

The structure of the individual Icelandic sagas does not follow a uniform narrative structure. It is characteristic that apart from an introductory prologue there are hardly any scenes that are not directly linked to the main plot of the saga. The main plot is sometimes overlaid by a series of individual episodes, so that it is difficult to see. Occasionally, events are excluded or only hinted at that were assumed to be known by the audience.

Einar Ó has another system for determining the age of the Íslendinga sögur. Sveinsson worked out. Its structure is based on the following qualitative criteria:

- References to Icelandic sagas in other contemporary works;

- Age of manuscripts;

- Occurrence of historical persons or events (as a model or inspiration for the author of the saga);

- literary connections between saga and other work ;

- linguistic criteria;

- Influences of spiritual or secular translation literature ( language and style );

- artistic form of the saga ( narrative structure , dialogue , style and narration ).

Many of the Íslendinga sögur contain stanzas from the skaldic poetry , so-called loose stanzas ( Lausavísur ), which in the sagas were usually composed impromptu on the occasion of special events and spoken immediately. In many sagas, however, these skaldic stanzas are poems added later . It is conjectured that these stanzas, as poetic kernels , asked to surround them with prose representations . Especially the oldest Íslendinga sögur, Nordals Level 1, are remarkably rich in Scaldic stanzas.

structure

The Íslendinga sögur group their plot around an increasingly dramatic conflict that is approaching a climax and that has a decisive influence on the fate of the protagonists. The conflict is the backbone of the saga as a literary genre . It organizes the relationship between two individuals, between an individual and a social or related group, or between two such groups, which are generally connected in different ways by close relationships. This conflict:

- polarizes the plot of the saga;

- forms the narrative unit of a saga;

- constitutes the dramatic tension of a saga;

- shapes their unique character;

- is the organizing principle of the saga;

- gives the saga its meaning.

The Íslendinga sögur owe their very existence to the experience of social crises that must be overcome by the social groups affecting them so that their existence is not threatened. The social function of the Íslendinga sögur is the need to reach reconciliation beyond the climax of a conflict that was perceived to be norm-resolving . The Íslendinga sögur are ultimately a dramatization of social events, legal and ritual processes, which serve to restore the recent past, the conditions and relationships before the conflict broke out. The final reconciliation required for this requires rituals ( institutions ) that restore the broken norm, the social order, and initiate a return to social equilibrium. Like Greek drama and theater in general, the final dramatization of Íslendinga sögur is at its climax an exaggeration of legal and ritual processes.

| Structure of social drama (after Victor Turner) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Detachment | Liminality | integration |

| Separation ritual | Threshold transformation ritual | Inclusion ritual |

| escalation | catharsis | reconciliation |

| Breaking the norm | Norm-free | Confirmation of the norm |

The Icelandic sagas as social dramas

The Íslendinga sögur thematize kinship relationships between neighboring social groups and their territorial affiliation to mutually delimited geographical regions: the farm as an economic unit of production, hamlets made up of several farms, geographical landscapes cultivated by farmers. The background against which an Íslendinga saga unfolds its narrative elements and motifs is a complex, interdependent social-geographic network in which the social relationships of the protagonists are constituted and developed. The Íslendinga sögur draw their main themes from social organization, family and political relationships, which are the focus of every culture , including the old Icelandic. The sagas find their object in the spatial and social positioning of the individual and the social group to which he belongs, integrated into the structure of larger communities such as lineage , clan or political system. Both genealogy and territory (in the sense of socially defined territorial affiliation) define the personal and ethnic identity of the individual.

The Icelandic sagas, conceived as poetry (handed down orally ) and literature (handed down in writing), are a culture-specific form of artistic expression whose primary function is to pass on genealogical and territorial relationships in the form of a chronicle . Secondly, they also want to entertain their audience, an intention to which the narrative artistic production, which originated from around the middle of the 12th century to the first half of the 14th century and whose prose works are now referred to as saga literature, can be traced back . This function, first and foremost of being a chronicle, and first of all a narrative, is related to the intention to give future generations their social orientation: to communicate to the individual who he is, from whom he is descended and to whom he belongs. Íslendinga sögur offer their audience, whether told or read (aloud), the necessary identity-creating and identity-stabilizing information: social, geographical, historical, legal and political. The naturalistic sagas thus tie in with a tradition that mythological-esoteric poems of the Edda songs also cultivate: the oral and written transmission of lists of names, lists of places and ancestral father catalogs (cf., for example, the Eddic poems Grímnismál , Völuspá in skamma , Hyndloljóð ) . While the Eddic poems relate their genealogical and territorial themes to the supernatural mythology of the world of the gods, the sagas draw the audience's attention to man with his everyday conflicts and hopes, to his strategies for solving and coping , which serve him, natural and resistant regulate social conditions.

Family relationships ( lineage and clan ), the focus of the social organization of a culture, define the chorological and chronological location of the individual and social group in the structure of the community. Genealogy and territory configure important aspects of the individual's identity in the Eddic poems and sagas.

The dramatic events in which their protagonists get entangled over generations, which are described in the Íslendinga sögur, can only be understood by those who can understand the reasons and motivations for the changing alliances that genealogically and socially connected groups enter into. Without a knowledge of the genealogical relationships and the social system of agnant and affinal relationships, there is no topic for the Íslendinga sögur.

Important Icelandic sagas

1. The West Quarter

- Bjarnar saga Hítdœlakappa - "Saga of Björn the Hitdœla fighter" (3)

- Egils saga Skallagrímssonar - "Saga of the Skald Egill Skallagrímsson" (2)

- Eyrbyggja saga - "Saga of the people of Eyr" (6)

- Fóstbrœðra saga - "Saga of the oath brothers" (10)

- Gísla saga Súrssonar - "Saga of Gísli Sursson" (9)

- Gunnlaugs saga ormstungu - "Saga of Gunlaug Wormtongue" (5)

- Hávarðer saga Ísfirðings - "Saga of Hárvarðr from the Icefjord" (11)

- Hœnsa Þóris saga - "Saga of the Chicken Thorir" (4)

- Laxdœla saga - "Saga of the people from Laxárdalr" (7)

- Bárðar saga Snæfellsáss - "Saga of Bárður Snæfellsás"

2. The north quarter

- Bandamanna saga - "Saga of the Allies" (12)

- Gretti's saga Ásmundarsonar - "Saga of Grettir Ásmundarson" (14)

- Hallfreðar saga - "Saga of the Skald Hallfreðr Óttarson" (17)

- Heiðarvíga saga - "Saga of the fight on the high moor" (15)

- Kormák's saga - "Saga of Kormák the love poet" (13)

- Ljósvetninga saga - "Saga of the people of Ljósavatn" (21)

- Reykdœla saga (ok Víga-Skútu) - "Saga of Vémundr from Reykjadalr" (22)

- Valla-Ljóts saga - "Saga of Goden Valla-Ljót" (19)

- Vatnsdœla saga - "Saga of the people from Vatnsdalr" (16)

- Víga-Glúms saga - "Saga of Víga-Glúm" (20)

3. The East Quarter

- Droplaugarsona saga - "Saga of the sons of Droplaug" (27)

- Hrafnkels saga Freysgoða - "Saga of the Freyspriest Hrafnkell" (28)

- Þorstein's saga hvita - "Saga of Thorstein the White"

- Vapnfirðinga saga - "Saga of the people of Vápnafjord" (23)

4. The south quarter

- Brennu Njáls saga - "Saga of the sage Njál" (29)

More Icelandic sagas

literature

- Thule Collection , Old Norse Poetry and Prose, Vols. 1-24, edited by Felix Niedner and Gustav Neckel, Jena, 1912-1930.

- Jan de Vries : Old Norse Literary History , Volume 2: The literature from about 1150 to 1300. The late period after 1300. de Gruyter, Berlin, 1967, page 314-463.

- Theodore M. Andersson , The Problem of the Icelandic Saga Orign. A Historical Survey, London, 1964.

- Theodore M. Andersson , The Icelandic Family Saga. An Analytic Reading, London, 1967

- Walter Baetke , Die Isländersaga, Darmstadt, 1974.

- Sagnaskemmtun, Studies in Honor of Hermann Pálsson, Vienna - Cologne - Graz, 1986.

- Tilman Spreckelsen : The Murder Fire of Örnolfsdalur and other Icelanders sagas. Berlin: Galiani, 2011.

- Klaus Böldl, Andreas Vollmer, Julia Zernack (eds.): The Isländersagas in 4 volumes with an accompanying volume . Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2011, ISBN 978-3-10-007629-8 .

Web links

- Íslendinga sögur ( Old Norse )

- Íslendinga sögur ( Icelandic )

- Extensive collection in various languages (including German) and file formats (HTML, PDF, EPUB, plain text) ( index )

Footnotes

- ^ Peter Hallberg: The Islandic Saga . Translated with Introduction and Notes by Paul Schach. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska 1962, ISBN 978-0-8032-5082-6 , Chapter 5: Oral Tradition and Literary Authorship, History and Function in the Sagas of Icelanders, pp. 49 (English).

- ^ Franz Seewald: Skalden Sagas , Insel Verlag 1981, p. 18 f.