West Yiddish dialects

The West Yiddish dialects (formerly also called Jewish German ) are those dialects in the areal continuum of the Yiddish language that were spoken in the western and central part of Central Europe . Spatially, they corresponded roughly to the settlement area of the Ashkenazi Jews that existed before their late medieval expansion and expulsion to East Central Europe and Eastern Europe. In the latter, the East Yiddish dialects developed , which are still spoken today and which formed the basis for the modern Yiddish literary language.

The Ashkenazi culture, which gained a foothold in Central Europe in the 10th century, derived its name from Ashkenaz, the medieval Hebrew name for Germany ( Genesis 10 : 3). Its geographical scope was not congruent with the German Christian territories, but also included parts of northern France and northern Italy . It bordered the area inhabited by the Sephardic Jews, which at that time stretched from Spain to southern France and Italy.

origin

The colloquial language of the first Jews in Germany is not known for sure. Since many Jews who immigrated to Germany presumably arrived via northern France, but also Italy and Danube Romance, one can assume that they spoke Romance idioms. Traces of this can still be seen today in the Yiddish vocabulary. The first language of European Jews may also have been Aramaic, the colloquial language of the Jews in Palestine during Roman times and in ancient and early medieval Mesopotamia . The widespread use of Aramaic among the large non-Jewish Syrian trading population of the Roman provinces, including those in Europe, had increased the use of Aramaic in trade.

Members of the young Ashkenazi community encountered Upper and Central German dialects. They soon spoke their own variants of German dialects themselves, mixed with linguistic elements that had brought them to the area. These dialects adapted to the needs of the burgeoning Ashkenazi culture and, as it characterizes many such developments, included the deliberate cultivation of linguistic differences to emphasize cultural autonomy . The Ashkenazi community also had its own geography, with a pattern of local relationships somewhat separate from that of its non-Jewish neighbors. This led to the emergence of Yiddish dialects, the borders of which did not coincide with the borders of German dialects. In general, Yiddish dialects each covered a much larger area than the German dialects, as the West Yiddish dialects raised in the 19th and 20th centuries showed.

Yiddish retained a small number of Old Romanic words, with some more common in West Yiddish than in East Yiddish. examples are בענטשן (bentshn) 'to thank after meals', from Latin benedicere, and, only West Yiddish, orn 'pray', from Latin orare, but also aboutלײענען (leyenen) 'read' andטשאָלנט ( tsholnt ), a Sabbath stew that is easy to keep warm, as well as a certain number of personal names.

Written evidence

The oldest extant, purely Yiddish literary document is a blessing in a Hebrew prayer book from 1272:

- גוּט טַק אִים בְּטַגְֿא שְ וַיר דִּיש מַחֲזֹור אִין בֵּיתֿ הַכְּנֶסֶתֿ טְרַגְֿא

transliterated

- good tak im betage se waer dis makhazor in beis hakneses terage

and translates,

- May a good day come to him who carries this prayer book into the synagogue .

This short rhyme is decoratively embedded in a purely Hebrew text. Nonetheless, it shows that Yiddish at the time was a more or less regular Middle High German into which Hebrew words - makhazor (prayer book for the high holidays ) and beis hakneses ( synagogue ) - had been inserted.

In the course of the 14th and 15th centuries, songs and poems began to appear in Yiddish and macaronian pieces in Hebrew and German. These were collected by Menahem ben Naphtali Oldendorf at the end of the 15th century . At the same time, a tradition apparently emerged that the Jewish community developed its own versions of German profane literature. The earliest Yiddish epic of this kind is the Dukus Horant, which has been preserved in the famous Cambridge Codex T.-S.10.K.22. This 14th century manuscript was discovered in the genisa of a Cairen synagogue in 1896 and also contained a collection of narrative poems on subjects from the Hebrew Bible and the Haggadah .

Aside from the obvious use of Hebrew words for specifically Jewish artifacts, it is very difficult to judge how far written Yiddish from the 15th century differed from German of that time. Much depends on the interpretation of the phonetic properties of Hebrew letters, especially the vowels. There is an approximate consensus that Yiddish sounded different to the average German, even if no Hebrew lexemes were used.

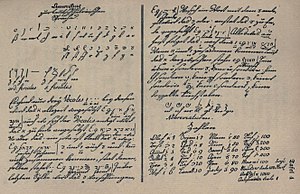

Printing units

The advent of the printing press increased the amount of material produced and survived from the 16th century . A particularly popular work was Elijah Levita's Bovo book , written 1507–1508 and printed in at least 40 editions since 1541. Levita, the first Yiddish author known by name, also wrote Paris un Vienne . Another Yiddish retelling of a courtly novel, Widuwilt, is believed to date from the 15th century, although the manuscripts are from the 16th century. It is also called Kini Artus Hof , an adaptation of the Middle High German courtly novel Wigalois by Wirnt von Gravenberg. Another important writer was Avroham ben Shemuel Pikartei, who published a paraphrase of the book of Job in 1557 .

Traditionally, women in the Ashkenazi community were not literate in Hebrew, but they did read and write Yiddish. Hence, a wide literature developed mainly for women. This included secular works such as the Bovo book and religious writings specifically for women such as Ze'enah u-Re'enah and the Tchins . One of the most famous early authors was Glikl bas Judah Leib , known as Glückl von Hameln, whose memoirs are also available today.

When West Yiddish religious literature was specifically aimed at women, the term “women's German” was often used up until the early 20th century; there was also a special Hebrew printing type for such literature aimed at women .

Decline of West Yiddish

From the 18th century, the spoken West Yiddish dialect was mainly replaced by German . Among other reasons, the Enlightenment and the spread of the Haskala to Western Europe in Germany led to the view that Yiddish was a bad form of their language. Between the assimilation to German and the initial creation of Ivrit, West Yiddish survived only as the language of familiar family circles or close-knit trading groups . Further east, where the Jews were denied such emancipation and where the coexistence of different peoples, each with their own cultures, continued to be an unbroken reality, Yiddish was the cohesive force in a secular culture based on and as such on ייִדישקײט ( yidishkayt 'Jewishness') was designated.

In the course of the 18th century the center of Yiddish printing shifted from West Yiddish to East Yiddish. Works previously printed in Germany, which have now been reprinted by printing companies in Poland-Lithuania , have been continuously adapted to the East Yiddish language. West Yiddish elements that were known (such as the neutral gender or the use of sein as an auxiliary verb) at least in part of East Yiddish were usually retained, even if they were unknown at the (Lithuanian) location of the printing house; those West Yiddish elements that (such as the use of wer (de) n to form the future tense or the past tense) were not familiar with the East Yiddish dialect were abandoned.

On the eve of World War II , there were between 11 and 13 million Yiddish speakers, of whom only a tiny fraction still spoke West Yiddish. The Holocaust , but also assimilation and finally the status of Ivrit as the official language of Israel led to a dramatic decline in the use of the Yiddish language. Ethnologue estimates that there were 1.5 million speakers of East Yiddish in 2015, whereas West Yiddish, which is said to have had several 10,000 speakers on the eve of the Holocaust, is said to have a little over 5,000 speakers today. The figures relating to West Yiddish are of course in need of interpretation and should almost exclusively relate to people who only have residual skills in West Yiddish and for whom Yiddish is often part of their religious or cultural identity. In Surbtal , Switzerland , whose West Yiddish dialects are generally counted among those that have been spoken the longest, Yiddish died out as a living language in the 1970s.

bibliography

- Vera Baviskar, Marvin Herzog a . a .: The Language and Culture Atlas of Ashkenazic Jewry. Edited by YIVO. So far 3 volumes. Max Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 1992-2000, ISBN 3-484-73013-7 .

- Franz J. Beranek : West Yiddish Language Atlas. N. G. Elwert, Marburg / Lahn 1965.

- Joshua A. Fishman (Ed.): Never Say Die. A Thousand Years of Yiddish in Jewish Life and Letters. Mouton Publishers, The Hague 1981, ISBN 90-279-7978-2 (in Yiddish and English)

- Jürg Fleischer : West Yiddish in Switzerland and Southwest Germany. Sound recordings and texts on Surbtaler and Hegauer Yiddish. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2005 (supplements to the Language and Culture Atlas of Ashkenazic Jewry 4).

- Carl Wilhelm Friedrich: Lessons in the Jewish language and script, for use by scholars and ignoramuses. Frankfurt am Main 1784.

- Florence Guggenheim-Grünberg : The language of the Swiss Jews from Endingen and Lengnau. Jüdische Buchgemeinde, Zurich 1950 (contributions to the history and folklore of the Jews in Switzerland 1).

- Guggenheim-Grünberg, Florence: Surbtaler Yiddish: Endingen and Lengnau. Appendix: Yiddish language samples from Alsace and Baden. Huber, Frauenfeld 1966 (Swiss dialects in tone and text 1, German Switzerland 4).

- Guggenheim-Grünberg, Florence: Yiddish in the Alemannic language area. Juris, Zurich 1973 (contributions to the history and folklore of the Jews in Switzerland 10), ISBN 3-260-03438-2 . [Linguistic Atlas; includes not only the Alemannic, but also parts of the Franconian area.]

- Guggenheim-Grünberg, Florence: Dictionary on Surbtaler Yiddish. The terms of Hebrew-Aramaic and Romance origins. Some notable expressions of German origin. Appendix: Frequency and Types of Words of Hebrew-Aramaic Origin. Zurich 1976, reprint 1998 (contributions to the history and folklore of the Jews in Switzerland 11).

- Dovid Katz : Words on Fire: The Unfinished Story of Yiddish. Basic Books, New York 2004, ISBN 0-465-03728-3 .

- Dov-Ber Kerler: The Origins of Modern Literary Yiddish. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1999, ISBN 0-19-815166-7 .

- Lea Schäfer: Linguistic imitation: Yiddish in German-language literature (18th – 20th century). Language Science Press, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-946234-79-1 [the book also contains a detailed overview of West Yiddish (phonology, morphology, syntax, lexicons) as it can be reconstructed from 19th century literature ].

Web links

- Language and Cultural Archive of Ashkenazic Jewry (Columbia University)

- West Yiddish at Ethnologue

- Collection of Yiddish printed works from the 16th to the 20th century

- Bibliotheca Iiddica. Small encyclopedia on Yiddish. Main page is in Latin, the rest of the content of the page is mostly in transliterated Yiddish.

- Entry on Yiddish - Jewish Encyclopedia

- Master's thesis with a good overview of the different approaches in West Yiddish dialectology.

Individual evidence

- ↑ The reason for the lack of clarity is that Northwest Yiddish and East Midwest Yiddish (which, as I said, not all authors call that) from High German a. a. Languages of the Christian population have been displaced and are therefore little researched. See e.g. B. the overview in this master's thesis p. 3–12 ( Memento of October 30, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Yiddish.

- ↑ Jerold C. Frakes: Early Yiddish Texts 1100–1750. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-926614-X .

- ^ Jean Baumgarten (translated and edited by Jerold C. Frakes): Introduction to Old Yiddish Literature. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2005, ISBN 0-19-927633-1 .

- ↑ reproduction.

- ↑ 1949, critically edited by Judah A. Joffe ( online ).

- ↑ 1906 in the Jewish Encyclopedia , in English; Hannah Karminski used the word as a matter of course in 1928 in an essay about Glückl von Hameln

- ^ Hebrew typography in German-speaking countries , reference from the Cologne University of Applied Sciences to so-called Weiberdeutsch letters

- ↑ Sol Liptzin: A History of Yiddish Literature. Jonathan David Publishers, Middle Village, NY, 1972, ISBN 0-8246-0124-6 .

- ↑ On this Dov-Ber Kerler: The Origins of Modern Literary Yiddish. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1999, ISBN 0-19-815166-7 .

- ^ Neil G. Jacobs: Yiddish. A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2005, ISBN 0-521-77215-X .

- ↑ Ethnologue.

- ↑ Ethnologue.

- ↑ See Jürg Fleischer: West Yiddish in Switzerland and Southwest Germany. Sound recordings and texts on Surbtaler and Hegauer Yiddish. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2005 (supplements to the Language and Culture Atlas of Ashkenazic Jewry 4), p. 16 f.

- ^ Critical review of Florence Guggenheim-Grünberg in the Zeitschrift für Mundartforschung 33, 1966, pp. 353–357 and 35, 1968, pp. 148–149.