KV60

|

KV60 |

|

|---|---|

| place | Valley of the Kings |

| Discovery date | Spring 1903 |

| excavation | Howard Carter , Edward R. Ayrton (1906), Donald P. Ryan (1989) |

| Previous KV59 |

The following KV61 |

KV60 ( Kings' Valley no. 60 ) denotes an ancient Egyptian tomb in the Valley of the Kings . Based on an inscription on a found wooden coffin of Queen Hatshepsut's wet nurse , Sitre-In , it was dated to the 18th Dynasty ( New Kingdom ).

Discovery and excavation

The grave was discovered in 1903 by Howard Carter , who at the time was working for Theodore M. Davis and at the same time chief inspector of the Egyptian Antiquities Administration ( Service des Antiquités d'Egypte ) in Upper Egypt and Nubia . Carter's investigation of KV60 was fleeting. He did not draw up a plan of the tomb, but noted its location. He published the results of this excavation in the same year in Annales du service des antiquités de l'Égypte . Three years later, Edward R. Ayrton , who was now the Egyptologist working for Davis, came across the tomb again. He did not draw up a plan of the tomb either.

After that, KV60 was forgotten until it was rediscovered in 1989 by Donald P. Ryan of Pacific Lutheran University and excavated until 1990. The work was carried out as part of a project, the aim of which was to find, examine and document graves in the Valley of the Kings that were already known but then lost again. According to the condition at the time it was recently uncovered, KV60 had not been entered after the visits by Carter and Ayrton. Ryan published his excavation results in KMT - A Journal of Ancient Egypt, among others .

Location and architecture

KV60 is located in the southeastern area of the Eastern Valley in the Valley of the Kings near KV19 ( Montuherchepschef ) and opposite KV20 ( Thutmosis I and Hatshepsut ). The grave axis is straight. The grave can be reached via a steep staircase that turns into a corridor, at the end of which is the 55.66 m² grave chamber. A small side chamber (5.01 m²) leads off the corridor.

All the walls in the grave are uneven and only roughly hewn, not smoothed and not plastered. As a result, it has an asymmetrical shape that cannot be found in comparison with royal tombs discovered in the valley. An originally planned use for a member of a royal family would thus be excluded.

The only decoration is made up of two udjat eyes , which are installed in niches opposite one another at the beginning of the corridor. These signs with amulet character can often be found on coffins since the New Kingdom. The "viewing direction" of the Horus eyes is different, so one looks into the inside of the grave towards the burial chamber, the other looks out towards the grave entrance.

Finds

Howard Carter noted the remains of a heavily robbed burial as well as two mummies and some mummified geese when he was discovered in 1903. In his report, he described the mummies as "older people" who were very well preserved and had long golden hair. Only the bottom of the coffin remained, the lid was missing. The only thing he described as "of value" was the coffin with hieroglyphic inscriptions. Carter removed the geese but left both mummies and the coffin in place and resealed the tomb.

After Edward R. Ayrton reopened the tomb in 1906, he had the coffin tub and the mummy inside brought to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. At what point in time this took place is not known. The second mummy, which had been lying on the floor next to the coffin, he also left in the grave.

After the grave was rediscovered in 1989, the finds, in addition to the mummy that had remained in the burial chamber, included scattered and mummified food supplies, ceramic fragments, parts of burial equipment, parts of jewelry, mummy bandages, scarabs , tools and mummified mammals. The wooden coffin surfaces that Howard Carter had mentioned were still there. As already noted by Carter, these were worked with an ax in ancient times in order to remove the gold foil from the surface. There were also numerous pieces of cardboard that came from the surface of the coffin. One of the larger pieces of wood was partly covered with a black substance, but also showed blue-green lines that indicated a painted headdress. Upon closer inspection, Ryan discovered something on the piece "that looked like a hieroglyph" in 2008. The wood was cleaned by a conservator, whereupon not only a text with a name became visible, but also a representation of the goddess Nephthys , who speaks the funeral text for a temple singer named Ty. However, the inscription is a bit fuzzy in parts and the name was probably written on top of another. The original version appears to have been written for a man. Another piece from the foot end has also been cleaned and shows a representation of the goddess Isis .

The ceramic remains could not be dated before the 20th Dynasty, which is why Donald P. Ryan assumes that the grave dates from this time. Another possibility is that KV60 was created in the 18th dynasty but not used, and in ancient times it happened by chance during the work for KV19 , the grave of Montuherchepschef , a son of Pharaoh Ramses IX. , has been discovered.

The situation in which the mummies were found suggests that one or even both were originally buried at a different location and were reburied at an unspecified point in time after KV60. Such transfers were not uncommon and are attested for other graves in the Valley of the Kings, such as KV35 and KV55 . According to the other finds, which must have come from different places, Donald P. Ryan considers this grave to be a hiding place.

Identification and examination of the mummies

The history of the assignment of the identities of the mummies is very changeable. Percy E. Newberry , who was present at Howard Carter's excavation, suspected that the two mummies were the wet nurses of Thutmose IV , whose grave ( KV43 ) is nearby.

When Ayrton had the mummy with coffin brought to Cairo and it was not inventoried there until 1916 with TR24.12.16.1, according to the inscription on the coffin, it was assumed that a lady named Sitre-In (or just called "In") was the nurse of Queen Hatshepsut, who was already known from a sandstone stele (JE 56264) found in Deir el-Bahari .

When Donald P. Ryan found the mummy remaining in the grave, the long hair had come off the skull and lay under the head. The left arm was bent over the chest in the burial posture typical of ancient Egyptian queens. The teeth turned out to be very worn on closer examination, which speaks for an elderly person. It was also found that the mummified person was quite stout. During the mummification, the viscera had not been removed through the lower abdominal wall as usual, but through the pelvis. In 1966, Elizabeth Thomas suspected that Queen Hatshepsut's mummy was in this mummy, which, in her opinion, spoke not only of the utensils found that could be assigned to a king, but also of the arm position. Donald P. Ryan also saw that of Hatshepsut in this mummy. Before the grave was closed again in 1990, the mummy was placed in a wooden box for protection.

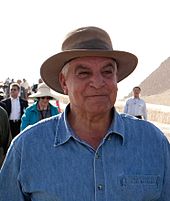

In 2006, Zahi Hawass reopened the grave in the Valley of the Kings as part of a film work on the Discovery Channel and began his “search for the mummy of Queen Hatshepsut”, which the film was supposed to document. The queen's mummy was not in the “ royal cachette of Deir el-Bahari ” (DB / TT320) and was considered “lost”. Unlike Thomas and Ryan, Hawass came to a different conclusion about the identity of the mummies. The mummy originally identified as Hatshepsut's nurse is that of the queen, since the face appears “quite royal”, and the mummy left in the grave is that of the nurse Sitre-In. The arm position does not have to indicate a queen. Hatshepsut's mummy was said to have been placed in the coffin of her wet nurse for protection during the 21st or 22nd Dynasty. The mummy was brought to Cairo a year later.

The examinations of the two mummies, now known as KV60A and KV60B, took place in 2007. In a project sponsored by the Discovery Channel and led by Zahi Hawass, various mummies were to be examined using CT . The aim was on the one hand to determine family similarities or connections from the time of the Thutmosids and to be able to make appropriate assignments, and on the other hand to determine which of the two mummies could be that of Hatshepsut. Among the mummies examined were those of Thutmose II , Thutmose III. , the putative mummy Thutmose I , all three of which have been found in the Deir el-Bahari cachette, and two female unknown mummies. In addition to radiological methods, the investigations also included the determination of DNA . For this purpose, a laboratory was set up in the Egyptian Museum as part of the documentation Secrets of Egypt's lost Queen .

KV60A

In comparison with all investigated mummies, KV60A showed similarities in the shape of the skull with those as Thutmose II. And Thutmose III. identified mummies. To determine Hatshepsut's mummy, various objects that could be assigned to Hatshepsut were also included in the investigation.

Among them was a small box (JE 26250) with the cartouches of the name of the throne ( Maat-Ka-Re - Justice and life force of Re - discovered by the Abd el-Rassul family in 1871 and vacated by Emil Brugsch in 1881 found by Deir el-Bahari) ) and the proper name of Hatshepsut ( Hat-schepsut-chenemet-Amun - the first of the ladies to hug Amun ). Inside the container was a mummified organ that was believed to be the liver or spleen. Gaston Maspero described the box in Les Momies Royales de Deir el Bahari in 1889 . The result of the CT examination showed the contents of a single molar that was missing a tooth root, the previously known wrapped, mummified organ and other, presumably organic material that could have come from the queen. The small box is therefore also known as the "canopic box", although a box of this type does not correspond to any previously known function of a canopic and is therefore extraordinary.

The CT examination of KV60A had shown that this mummy was missing a molar tooth in the upper jaw, but a broken tooth root had remained there. The tooth remnants were compared with the tooth from the box that was missing a root. Both were measured and the density of both was determined. Two teams worked independently of each other and came to the same results. Zahi Hawass published at the time that he had found the mummy of Hatshepsut:

Not only was the fat lady from KV60 missing a tooth, but the hole left behind and the type of tooth that was missing was an exact match for the loose one in the box from DB320! We therefore have scientific proof that this is the mummy of Queen Hatshepsut.

“Not only was the fat lady from KV60 missing a tooth, but the remaining hole and the type of tooth that was missing was an exact match with the loose tooth from the box from DB320! We therefore have scientific evidence that this is Queen Hatshepsut's mummy. "

This type of determination for unambiguous identification did not go unreflected and was viewed critically. The main point of criticism was that the tooth with roots found in the box cannot be a molar tooth from the upper jaw, as these teeth usually have three roots, whereas molars of the lower jaw have two. The radiologist Paul Gostner, who was a member of the second investigation team, explained that there are variations in tooth roots and that two roots can grow together into one. Therefore, this tooth can be an upper molar. Since the tooth was only examined radiologically in the box, there is also the possibility that a third root is among the loose fragments in the box or has been lost. Erhart Graefe, among others, was skeptical of the analysis . According to him, you cannot combine the data of a three-dimensional and two-dimensional representation, as was documented in this case.

It was also criticized that hardly any detailed research data was published, or that it was only published in pieces and that it was not published in a science journal. According to Ryan Metcalfe, this means that independent analysis and viewing of the data obtained is impossible.

The following results were recorded: The conservation status of the mummy KV60A is described as appropriate. The brain was not removed during the mummification and the heart was also left in the body. After the organs were removed, the abdomen was filled with linen packets. There had been massive abscess-related inflammation at the site of the gap between the teeth, which had been treated medically. The dental status was poor overall. Person KV60A also suffered from diabetes mellitus and cancer , as indicated by several malignant tumors . It was not possible to determine which of these illnesses led to the death of the person. The age was given as 50 to 60 years, the height was calculated to be 1.59 m.

The DNA comparison was carried out with samples from the mummies from KV60A, KV60B, Thutmose II., Thutmose III. and Ahmose Nefertari . The results were named tentative in the 2007 TV documentary Secrets of Egypt's lost Queen , and after Zahi Hawass' publication Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies. (2016) the results were still vague. As a final result, the determination by the comparison of the teeth of the mummy KV60A as that of Queen Hatshepsut remained, a result that is not shared by all Egyptologists.

A DNA comparison with the tissue removed from the mummy, the organ identified as the liver in the box and the tooth found in it was not carried out, so that the question of the organ's affiliation remains unanswered.

KV60B

The mummy of the royal nurse of Hatshepsut, Sitre-In, KV60B, had been identified by the partially preserved inscription “Great royal nurse, In, tru an voice” ( wr šdt nfrw nswt Jn, m3ˁ-ḫrw ).

For further investigation, however, the coffin and mummy of Hatsheput's nurse first had to be looked for in the Egyptian Museum. Photographic documentation was also not available at the time. The coffin and mummy were finally found on the third floor of the museum. The investigation found that Sitre-In was about five feet tall. The coffin in which she was found, however, was 2.13 m long, so that it can be assumed that this coffin was used for Sitre-In.

KV60B was very carefully mummified and wrapped in "the finest linen". The fingers were all wrapped individually, but the feet were wrapped together. The linen bandages in the coffin were of lesser quality than those used for the mummy. No information was given on the possible age or illness of this person. There were no similarities compared to the examined mummies of the royal line.

See also

literature

- Dylan Bickerstaffe: The Burial of Hatshepsut. In: The Heritage of Egypt. Issue 1, January 2008, pp. 2–12.

- Howard Carter : Excavations at Biban El-Moluk (1903) . In: Annales du service des antiquités de l'Égypte. Suppleménts 4. Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, Cairo 1903, pp. 167–177.

- Zahi Hawass , Francis Janot: Mummies. Witnesses to the past. White Star, Wiesbaden 2008, ISBN 978-3-86726-079-4 , pp. 42-47, p. 106.

- Zahi Hawass, Sahar Saleem: Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies. The American University Press, Cairo 2014, ISBN 978-97-74166-730 , pp. 54-62.

- Jo Marchant: The Shadow King. The bizarre afterlife of King Tutankhamun's Mummy. Da Capo Press, Boston MA 2013, ISBN 978-0-306-82133-2 , pp. 177-179.

- Ryan Metcalfe: Recent Identity & Relationship Studies, Including X-Rays & DNA. Hatshepust's Tooth. In: Richard H. Wilkinson, Kent R. Weeks (Eds.): The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press, New York 2016, ISBN 978-0-19-993163-7 , pp. 384, 404-405.

- Nicholas Reeves , Richard H. Wilkinson : The Valley of the Kings. Mysterious realm of the dead of the pharaohs. Econ, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-8289-0739-3 , pp. 186-187.

Web links

- Theban Mapping Project: Theban Mapping Project: KV60 (English)

- Donald P. Ryan: Egyptian Archeology: Valley of the Kings! Images for KV60 , accessed on April 24, 2017.

- Pacific Lutheran University. Valley of the Kings Project: KV 60: An enigmatic and controversial tomb. , February 24, 2016, accessed April 24, 2017.

- Mark Rose on Archeology Online: Hatshepsut Found; Thutmose I Lost. , July 15, 2007, accessed April 24, 2017.

- Zahi Hawass on Guardians net: Quest for the Mummy of Hatshepsut. , March 2006, accessed April 24, 2017.

- Zahi Hawass on Guardians net: The Search for Hatshepsut and the Discovery of her Mummy. , June 2007, accessed April 24, 2017.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Nicholas Reeves, Richard H. Wilkinson: The Valley of the Kings. Mysterious realm of the dead of the pharaohs. Munich 1997, p. 187.

- ^ Howard Carter: Excavations at Biban El-Moluk (1903). In: Annales du service des antiquités de l'Égypte. Suppleménts 4. Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, Cairo 1903, pp. 167–177.

- ↑ Theban Mapping Project: Theban Mapping Project: History of Exploration ( Memento of the original dated November 30, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (English), accessed April 25, 2017.

- ↑ Nicholas Reeves, Richard. H. Wilkinson: The Valley of the Kings. Mysterious realm of the dead of the pharaohs. Munich 1997, p. 186.

- ↑ Zahi Hawass: Quest for the mummy of Hatshepsut. In: KMT. A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt. Issue 17, number 2, summer 2006, p. 41.

- ↑ Nicholas Reeves, Richard. H. Wilkinson: The Valley of the Kings. Mysterious realm of the dead of the pharaohs. Munich 1997, p. 186.

- ↑ Zahi Hawass: Quest for the mummy of Hatshepsut. In: KMT. A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt. Issue 17, number 2, summer 2006, p. 43.

- ^ The Search for Hatshepsut and the Discovery of her Mummy