Knocking (skinning)

The pounding of the furs , mostly with hazelnut sticks, was once one of the main tasks of the furriers . The widely audible, typical three-stroke was one of the hallmarks of the profession. By tapping loose dirt particles are removed, the hair is loosened and the pressure points created during processing are removed. With the decline in summer fur storage ( fur preservation ) and the invention of the fur knocking machine, this activity, especially in terms of the working hours, has lost its importance.

General

Before the invention of insecticides, insects were the main enemies of textiles and fur. Given the high value that fur represents, it was particularly worthwhile to invest some time or money in protection against such damage. Since the middle of the 18th century, this was done by furriers for fur goods as part of what has been known as “fur preservation” since the establishment of cooling rooms, at least to a small extent, this already happened in earlier centuries. An old textbook says: “ If they are not disturbed in their activity, it is a very terrible one, so the furrier endeavors not to make them happy in their life. "Therefore:" In the storage and conservation of the fur, the beater plays the first and most important role ". In 1897 it was said that the rooms for the furs given for summer storage were fumigated by the furrier with fir twigs or other softwood. In order to achieve the absolutely necessary dryness of the rooms, small amounts of gas or gunpowder were set on fire.

If the owner keeps his parts at home, it is advisable that he knock them through thoroughly before hanging them away in a room that is as cool as possible. The dust that has accumulated in the fur is removed and any caterpillars, insect larvae or eggs are smashed with appropriate care. To be on the safe side, this process should be repeated after a few weeks.

With the fur or clothes moth , it is not the moth itself that does the damage. In the period between the end of April and September, she lays her eggs in the woolly objects she considers suitable food, but is active all year round in heated rooms. Three weeks later, the caterpillars crawl out of it, initially doing their work unnoticed on the leather base in the case of Fur. It can remain undetected for a very long time, especially in the case of heavily matted pelts, such as beavers . Under optimal conditions, four generations of moths with 100 to 250 eggs per year each are possible. When the furrier gets the infected parts from the frightened customers, he usually only finds the empty pupal covers of the hatched larvae, apart from the sometimes considerable traces of food.

Naturally, when you tap, only the loose dirt is removed. A more thorough fur cleaning is the lautering with wood flour. Associated with this, specialist companies offer additional post-treatment, which is supposed to protect the fur from moth infestation over the long term, known as eulanizing . This replaces the previously used methods, protection through the use of camphor and naphthalene and other things, which also had an unpleasant odor and were only of limited effect.

Knock with your hand

A still existing instruction from 1699 to pick up and clean the fur of the Electress Anna Maria Luisa von der Pfalz, who resides in Düsseldorf, to her local furrier Johann Welen (Wolon) shows that at that time the fur workers were already taking care of the storage and the had taken care of the customer's furs. On July 2, the Electress paid four Reichstaler for this service, the number and type of furs kept and beaten for it was apparently not mentioned.

As a remedy against moth infestation in 1698, in addition to camphor and strongly smelling Biesem and Zibeth ( which some Weibs-people dislike ), strongly fragrant plants such as Veyhelwurz , Siebenzeit , Benedictenwurz , pure flowers and the like were mentioned. The best way, however, is to bring the clothes into the air and shake them out and knock them. The knocking and combing, however, must also be done in an expert manner; By tapping too lightly and too little the purpose of destroying the moths, larvae and eggs sitting in the fur is not achieved, by tapping too much the hair is easily tired and made to felt. A Weimar specialist book from 1844 mentions that the furriers in Russia should sprinkle powdered Marienglas into the hairy side of the fur, which would thus be protected, as the moths would not tolerate the fine tips of the powder particles. Before the fur could be used again, the powder had to be removed by tapping it out. At the same time it was pointed out that " the diligent knocking out of the fur, which has to be done much more often in summer than in winter, and subsequent combing, however, always remains an accurate means ".

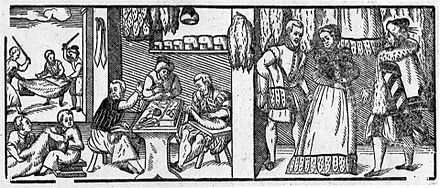

Most of the old furrier representations show how journeyman and apprentice knocking out fur or pelts , often on the street in front of the farm. This strenuous work, which kept journeymen and apprentices busy for many weeks, especially in spring and summer in some furrier's workshops, required a certain amount of care and practice (1891): “ ... how much more often are the complaints that the goods to be knocked are either not clean knocked or smashed, both of which are as unpleasant as possible. “The youngest employees in general had to do the knocking. For the knocking out of the cleaning shavings in the fur dressing shops in Leipzig, it was said in 1896 that the skins were mostly knocked by young boys and girls.

In the inventory of the Breslau master furrier Paul Lehnhardt, who died in 1582, the inventory of hand tools also includes “9 knocking sticks”. From the fact that the master found the sticks to be worth listing in the inventory, it can perhaps be concluded that even then they were not always cut themselves, but in this case were bought.

In 1762, the Prussian historian Johann Samuel Halle remembered how the Russian ambassador in Berlin found his precious sable fur, which was worth a few thousand thalers, completely destroyed by the moths, whether his servants had immediately poured a lot of pounded pepper all over it. When the furrier was supposed to knock him out, there were scarcely a few hundred thalers left undamaged; all the wool, along with the most important roots of the upper hair, was completely gnawed away. The ambassador had to be content at last, since the fur had only been packed up for one winter's journey, although he wanted to stab his servant in the first heat.

Hazelnut sticks are best for tapping; they are particularly straight, have a smooth rind without secondary branches and are roughly the right size , especially the wild shoots that form after the plants have been grafted. Cane sticks are less suitable for commercial use, they bend and do not produce the right effect.

Knocking was mostly done with both hands in a three-beat furrier. The two sticks were held loosely in the closed hand, two light blows were followed by a strong blow:

- . . -. . -. . -. . - etc.

Particularly heavy, thick-skinned pelts were pounded in six beats, only every sixth beat was a, but now particularly powerful, beat:

- . . . . . - . . . . . - . . . . . - etc.

The heavy blow should loosen the dirt and lift it up, the two light blows remove it from the part that was knocked. That is why this work was also carried out outdoors as far as possible, not only could the citizens loudly and effectively determine how carefully their furs given for summer storage are cared for. The wind did the rest to remove the dirt naturally. The blows followed one another so quickly that the part was in constant vibration. This effect could be further enhanced with a leather knocking cushion placed underneath. A trained journeyman could beat hundreds of times a minute. This produced a rising and falling noise that was hardly noticeable as a single knocking. A simpler beat sequence was also possible, in which a strong beat alternated with a weak one, but this led to a one-sided stress if the strong beat was not shifted to the other hand from time to time. However, every apprentice was proud when he mastered the furrier three-time rhythm, in which the powerful blow changes to the other hand every time. In addition to the reason for the skinning cycle mentioned at the beginning, there is also a simpler explanation. Knocking is much less tiring. It would be difficult to hold out for several hours if all strokes were done equally. This work took several weeks each year, especially in the larger farms with several thousand furs to be stored that were emerging at the end of the 19th century. Careful furriers repeated the process, now a little less thoroughly, several times in the course of the year in order to detect a possibly not completely removed moth infestation. How often the knocking has to happen, whether every four weeks or with a longer break, depends on the respective location of the rooms. Infested parts were separated so that they could be tapped from time to time, as the moth larvae often hid in the hems in places that were difficult to access. In addition, the goods that were hanging open for sale had to be checked and tapped again and again. However, the frequent taking in hand offered a certain security against the unnoticed moth infestation. The Leipzig tobacco wholesalers usually had their warehouse knocked through four times a year, especially in the quiet times, the first time after the fair at the end of spring. Sometimes unemployed market helpers (semi-skilled fur market assistants) were also employed on a temporary basis.

A man cleaned small objects, or two pelts at a time, by tapping evenly with one hand while holding the object in the air with the other hand. Sleeve contrast, could be treated in the tapping table with two sticks, with round socket (socket tons) conveniently turned on its own. Larger parts were often tapped in pairs. Experienced journeymen were able to meet one another in time; either with four sticks or with three if one hand was needed to hold the fur.

The monotonous work itself should not lead to carelessness, it had to be extremely careful . Not only the strength of the blows and the thickness of the sticks should be matched to the skin, but also the time required for a part varied. A chinchilla muff was to be treated differently than a bear fur , a black-dyed rabbit muff could sometimes be left untapped without the moths eating it. Foxes and other hard-curled long-haired pelts had to be pounded more carefully and briefly so as not to knock off the upper hair, as did strongly felted pelts. Curly pelts like Persians and Krimmers are also to be pounded more carefully so that the curl does not come loose. No point may be left out of the blows, and the hidden areas such as the hems must also be recorded. The pockets are to be brushed out. At the same time, matted areas are carefully combed out with a metal comb. For sheepskins is Kardätsche used provided with a hook wire brush, less aggressive is a simple wire brush.

Very heavy furs, for example bears with thick leather, on which nothing can be spoiled , were beaten with simple, heavy blows in threesomes, as when threshing . However, moth larvae or eggs cannot be removed with this alone. While hanging, also with simple, heavy blows, large rugs and fur blankets were dusted off.

Parts of bird skins were not pounded with a beating stick, but with a flat bed so as not to damage the plumage.

To protect after knocking in spring against a moth infestation parts was proposed, the fur then , best raw all over, comes in a good linnenes cloth even with the sizing laden canvas, and those from Weber to sew, that not the slightest Leave the opening and store them in a box or suitcase in a cool, dark, dry place .

The problem of moth infestation and knocking for the tobacco and fur trade, and that at a clumsy time, was described as follows in 1925: “In its further metamorphosis, the caterpillar spins itself into a pupa, as it does in hidden hiding places such as joints and cracks of the storeroom, overwintered to slip its white shell as a winged moth at the first rays of spring sun, especially between the Leipzig main [fur] fair and the London [fur] summer auctions. […] But the value of this work becomes illusory if only a single egg remains attached to the hair of a fur, which develops into a destructive caterpillar within a few days. In addition, as soon as this procedure is used too often, tapping through is enough to the detriment of the fur. It is only used in the tobacco industry for the reason that it is the method which, when used, can have the least adverse effect on the value of the fur, but without offering absolutely reliable protection against moths and fur beetles. "

After about 1910, the business office "industry association of furriers Austria" newly founded had become too small after a short time, " as was the newly built Central Palace on the Mariahilfstraße rented the entire top floor, the 14 rooms and two knock terraces [!] Had ."

In the 19th century there was also a considerable migration of German furrier journeyman towards the west. The furriers in Paris, especially the global Revillon Frères , were still dominated by German-speaking workers around 1900. There was even a German furrier singers' club in Paris, "Lyra". In 1902, in the tradition of the Mastersingers , all experts were called upon to rhyme "The Song of the Furriers" in a competition:

- When the leaves fall from the trees in autumn

- Then the furriers cheer and sing,

- Full of joyful courage, pockets full of money,

- They swing the beater in rhythm ...

Everyone beats the skinning time on their knees and sings: 'Tra, la, la'.

- “Goodbye now”, so the winged crowd hums

- Of the moths, "you hairy brothers",

- Just knock and blow hard in your hair,

- We'll see each other again in the summer.

The winning song from the 13 entries was then set to music by professor and composer Alois Strasky, son of a Viennese master furrier. The triad when knocking was chosen as the leitmotif :

- We furriers, we are happy people, have traveled far across the country

- To see what beautiful the earth praises us, the heart lifts and the eye delights

- What is the use and benefits of our class ...

As melodious as the knocking sometimes accompanied by songs might have been, there was a local need to forbid this work at least at night. After mentioning the presumably noisy brass bats , which were similar elsewhere, the following is quoted: " Other noisy trades also had to limit themselves: So the Buxtehude furriers called the" bedeglocke "for the end of work ." And Krünitz wrote in 1794: " They are the neighborhood, where they live, with the din of the knocking out of their skins, and with the stench of the furrier stain, arduous. One also finds judgments (Praeiudicia) that a furrier has been ordered not to knock out the skins in the street but in his house or yard, and also to pour out the stain only at night . "

In Nyíregyháza , Hungary , not far from Slovakia, there was a custom of celebrating the "cutting of the rod" on the day of St. John on March 19. The furriers then went on a trip together into the forest, where they cut hazel rods together. As a kind of consecration, the apprentices were beaten with it, presumably in skinning time, and sang:

- If the lamb still wears its fur,

- the Kürschnerg'sell is already boiling.

The knocking beat in peasant threshing with the flail is equivalent . In Lower Saxony, threshing was done in three, four or six times. At the three-stroke it said: “ You are up to it! It's your turn !, you are ... "; in four-bar: “ Sla you man to'u! I can't yet! Sla you ... "and at the six- beat :" Jag'n Hund rut! Chase the calico! Vo'n düt Hus, Na düt Hus, Von'n Spieker, Na'n Backhus! "

A collective agreement was concluded in Cologne on September 12, 1905, after the furriers' employers had founded an association. A daily allowance of 25 pfennigs was agreed for the time of the strenuous knocking work. The Austrian furriers' collective agreement of 1933 stipulated knocking allowances for skilled workers: “In companies that knock by hand or only with the help of small mechanical auxiliary machines, the workers assigned to knock receive a knocking allowance of 13 percent to the respective hourly wage, or . Daily wage of a worker in class 2 “ (that was a supplement of 0.13 to 0.14 schillings). "Those companies that operate and so the cleaning of fur, storage of objects, in particular line of business and which are capable of this own forces to use are entitled to meet with the employees here own agreements outside this contract" .

Knocking with the fur knocking machine

- First tapping machines

With knocking shaft and tail turning device (1914)

Fur knocking machine with lauter tun (year of construction approx. 1971): The furs are knocked in the upper part. The handwheel is used to regulate the knock strength. The dust collection bag behind the machine. In the lower part there is the heatable refining barrel for cleaning fur. The lautering time is adjustable.

Below is the collecting box for the cleaning flour and loose hair. On the left is the lid for the compartment for small parts, next to it the shaking sieve for shaking out the lauter grain, then the lid for closing the large bin. On the right are different types of lauter flour (e.g. resin-free beech flour or Brazil nut shavings).

The first devices with which the monotonous knocking work was optimized and rationalized came about after the start of general electrification around 1900. In 1904, the designer Baum built the first two knocking machines in Germany. In an old company brochure he wrote

- One of them ran at the fur company Guido Pfeifer, Mannheim, B 1. 3, the other at Chr. Schwenzke, also in Mannheim, which were made entirely of iron. The reinforcement of the blows was done by raising and lowering the knocking table. This tapping machine was in operation at Schwenzke until 1936 and until then it met all requirements.

Initially, the devices still worked on the principle of the knocking stick. For the fur processing companies there were machines with endless conveyor belts with which the pelts were carried under the sticks. A machine with this technology was described in a GDR book in 1970. The German furrier magazine reported in 1934 that the then highly respected Berlin furrier Julius Herpich had brought the idea of the rotating tapping wave back with him from a trip to America before 1919, instead of the hazelnut sticks that were previously only in use . A major achievement of the machines from CA Herpich Söhne was pointed out: the simultaneous dedusting means that the dirt that had previously been created when knocking was completely collected. It could also be supplied with a fur cleaning barrel under the tapping device. The mentioned, presumably maximum output of 12,000 knocking strokes per minute is unlikely to have been used in practice. In 1915, however, Herpich was already advertising a fur-beating machine, available in four sizes, which had already been “brilliantly rated a hundred times in letters”: “Foldable, replaceable round belts, running on ball bearings, strong, solid construction. Replaces 12 experienced knockers ”.

The part to be knocked is moved by hand over the resilient knocking pad located under the shaft. The belt loosens the dust and transports it backwards into the collecting container, usually reinforced by a suction device. Leather straps do not break guard hair as easily as a cane, but there is now a risk of pulling the hair out. Therefore, and after assessing the durability of the leather, the knock strength, i.e. the speed of the knocking wave, must also be set according to the respective sensitivity of the skin.

Another self-builder of a tapping machine was the tobacco product refiner Hans Müller in Leipzig. The Leipziger Brühl was once the world center of the wholesale trade in fur. Numerous important fur finishing and finishing companies had sprung up around Leipzig . Müller's knocking machine was so popular that he specialized in mechanical engineering and became the leading manufacturer of all machines for refining tobacco products . In 1930 he was only recorded in the company register under "mechanical engineers".

After the Second World War, the Karl Hindenlang company dominated production for furrier businesses, at that time in Heidelberg, with tapping machines developed from the Baum system. From 1949 she manufactured skinning machines. She developed a space-saving universal machine, similar to that of Herpich, with which the furrier could purify (clean) the furs, then shake them to remove the lauter shavings and finally knock them. The accident-prone-looking lauter tun, which was still open at the Herpich machine, was now completely dressed. As one of the additional devices there was an insert that was supposed to be used to knock the pieces of fur that had been stored at the furrier for decades against a possible moth infestation. Another internationally leading machine factory , which in 1956 could look back on thirty years of specialist experience, was Otto Baumberger & Co in Leipzig-Wahren. Among other things, it produced quite a few different models of knocking machines.

For smaller businesses or as a supplement, hand-held knockers were manufactured, which apparently did not become particularly popular. In addition to using it to care for customer goods, an essential task of the beating machine is to remove the rest of the cleaning powder after shaking in the shaking barrel. This cannot be managed with the small hand-held devices, if only because the dust is not extracted. Nowadays furriers rarely beat their furs in the open air to use the wind for help.

As in skinning, pounding machines are also used in fur trimmings and fur refiners . During the individual finishing and dyeing phases, the pelts are beaten more often. In the past there were devices in which the knocking cylinder could be exchanged for other rolls for better utilization, such as straightening, Bakel, combing, brushing or roughening cylinders. In 1925, the daily tapping performance of a machine when operated by just one worker with 500 to 600 skins was specified. Regarding the lashing straps, it was noted that they wear out over time and then need to be replaced. However, because of the efficient operation of the machine, the costs for this would by far not be as high as for the permanent acquisition of sticks.

With the double drum tapping machine, it is preferable to tap large skins from both sides at the same time in order to remove any wood chips that may have stuck to the leather side. Because of its external shape, it is also called a heart-pounding machine. The upper and lower knocking waves run in opposite directions.

The air tapping machine works on a completely different principle. While with the other devices used in fur finishing , the machine moves and the fur rests, here it is the other way around. The skin, which is held in the air stream by hand, is made to flutter by the suction and strikes alternately and very quickly against the floor and ceiling of the wind tunnel. The loose hair to be removed is carried away by the draft.

In North America, pounding the pelts in the fur preservation is generally not common, here the pelts are blown out with compressed air instead. A study commission of German experts in 1925 found this to be more hygienic (probably because of the dust filtering of the knocking machines, which was mostly missing at the time) and more time-saving, but opinions differed about the overall advantages over knocking.

Poetry

- In 1924 the “Wiener Kürschnerzeitung” published a four-stanza “ Song of Praise to the Knocking Machine ”, which at that time was beginning to gain acceptance , especially in the larger companies:

" How hard it

was once

, when the journeyman army

was still struggling with staff and sticks , knocking furs, blankets,

[...]

Until finally the enlightenment came

with a full routine who

gathered his mind together

and created the knocking machine.

[...]

The large pile does not frighten him, he

never runs out of time again:

he

only knocks with the knocking machine with a cheerful expression . "

- In 1949, the renowned master furrier and leisure lyricist Adolf Nagel sent a poem to a specialist magazine with the title “ Three-stroke (from knocking) ”. It shows that knocking "with a stick and stick" was still used at the beginning of the second half of the 20th century:

“ The skin is pounded vigorously.

One, two, three in a skinning

cycle , […]

This blow works better

than a hundredweight of naphthalene.

[…]

If there are even traces of moths:

One - ha, how the food is already flying,

Then again at full speed,

Two, three until the stick bends.

Monthly three-stroke tapping

is a moth death extract.

[...] "

- The Swiss poet and politician Gottfried Keller (1819-1890) used moth-beating in a figurative sense. His slightly satirical sonnet "Auf die Motten" ends:

“ This is how those nimble moths speak,

They nest so comfortably in the smoke,

The warm, delicious, and gnaw on it.

"Only you are still to be exterminated

" (that's how we speak, the radical Christians),

to chase out of the fur with a gentle tap! ""

More knocking machines

- Company Wehling & Selbeck , Leipzig. An illustration in a fur finishing specialist book from 1925 shows a very simple belt tapping machine in which only the tapping shaft is covered, the belts are attached in a row next to one another. A special feature is the knocking table, which is pushed upwards under the knocking shaft on wheels with the knocked material. A glazed window allows a view of the part to be knocked.

- "König", with a flexible rod shaft, "which can be moved like a human arm" (1925).

- “Speed”, hand tapping machine “with tapping shaft and brush”. 1926 offered by Strauss, Vienna, Siebensterngasse 13.

- "Ideal" from J. Kulp, Munich. Manual belt tapping machines; Piece rapping apparatus; Brush roller, "best and cheapest of all tapping machines" (self-promotion). Offered at the Novelty Exhibition, Leipzig Easter Fair, April 15 - May 6, 1928. Can also be viewed at Philipp Manes , Berlin.

- "Schrom" from Carl Schrom, Borna Bez. Leipzig. Belt tapping machine with dust removal system (blower with dust bag); also open, without frame (250 marks). Offered at the Novelty Exhibition, Leipzig Easter Fair, April 15 - May 6, 1928.

- Three years earlier, the "Schrom" was advertised with "rotating stick knocker DRP", the "knocking and brushing machine" Schrom "strikes with sticks and straps". One illustration shows that the version “with sticks”, unlike the competing products, was not really a bat. Wooden rollers were fastened parallel to the tapping wave, the type and appearance of which they were formerly used as wooden handles for the more comfortable carrying of tied packages. An electrically heated lauter tun was located under the uncovered knocking table.

- Tapping belt machine, with the possibility of attaching a stick tapping device, the company Hermann Kettlitz, Jessen (Elster) , special machines and transport equipment manufacturing, a combined tapping machine with a lauter tun and a tapping machine of smaller dimensions. According to the company, for the first time also suitable for intensive pounding of pieces of fur .

- The aforementioned company Dr. Hans Müller , Spezial-Maschinen-Fabrik, Leipzig, had two knocking machines in his brochure in 1933. "Type KM" was a belt knocking machine with a hood and dedusting system, for dressing shops, finishing companies and furrier shops. Type "SKM", a stick beating machine with an automatic fur holding device, for beating all types of sheep and lambskins.

- It is described as follows:

- “The machine works with two sticks, which in total Gesch. Socket pieces are attached, whereby a breakage of these is almost impossible; In addition, an excellent tapping effect is achieved by means of these tapping sticks, which is far superior to that of hand tapping. Only one person is required to operate and the machine replaces several workers. The skins can be clamped and unclamped quickly using the foot lever. The jig is mobile so that the skin can be pounded through intensively in its entire width and length. [...] For protection, the sticks are provided with a hood, which also serves to suck off the dust. "

- Otto Baumberger & Co., Leipzig-Wahren, advertised fur tapping machines for manual operation with flexible shafts, stationary and mobile, in 1955. In addition, knocking machines with dust extraction, speed regulation, heatable, combined with a lauter tun.

- Type KI / 100 , a belt tapping machine from Rudolph Pöhlandt, Württ. Pelzmaschinenfabrik, Murrhardt. A very simple device, apparently intended especially for fur processing companies.

Web links

Niko-Laus! It is high time that your fur was knocked out thoroughly!

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c P. Larisch: The furriers and their characters . Self-published, Berlin 1928, pp. 156, 167, 175–176.

- ↑ a b c d e f Paul Cubaeus, "practical furrier in Frankfurt am Main": The whole of furring. Thorough textbook with everything you need to know about merchandise, finishing, dyeing and processing of fur skins. A. Hartleben's Verlag, Vienna, Pest, Leipzig 1891. pp. 169-172, 406.

- ^ A b Paul Larisch , Josef Schmid: Das Kürschner-Handwerk . Self-published, Paris without year (first edition, part I 1903), p. 32.

- ^ Jean Heinrich Heiderich: The Leipziger Kürschnergewerbe . Inaugural dissertation, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität zu Heidelberg, 1897, p. 95.

- ↑ Gaetan J. Lapick, Jack Geller: Scientific Fur Servicing . Fairchild Publications, New York 1952, p. 64.

- ↑ a b c Alexander Tuma jun: The practice of the furrier . Published by Julius Springer, Vienna 1928, pp. 230–232.

- ↑ Company publication: A small guide to tobacco refinement . Farbenfabriken Bayer Leverkusen, no year of publication, p. 53.

- ↑ Jürgen Rainer Wolf (eds.): The cabinet accounts of Electress Anna Maria Luisa von der Pfalz (1667–1743) , Volume 1. Klartext Verlag, Essen, 2015, p. 353.

- ↑ [1] Christoff Weigel : Illustration of the common-useful main stands From which regents and their servants assigned to / bit all artists and craftsmen in times of peace and war . Regensburg 1698, p. 618. Online edition of the Saxon State Library - Dresden State and University Library, last accessed April 7, 2014.

- ^ Christian Heinrich Schmidt: The furrier art . Verlag BF Voigt, Weimar 1844, p. 88.

- ^ Jean Heinrich Heiderich: The Leipziger Kürschnergewerbe . Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the high philosophical faculty of the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität zu Heidelberg, Heidelberg 1897, p. 74.

- ^ Fritz Wiggert: Origin and development of the old Silesian furrier trade with special consideration of the furrier guilds in Breslau and Neumarkt . Breslauer Kürschnerinnung (Ed.), 1926, p. 169. Primary source Breslauer Stadtarchiv ZP 1. 10 book covers and table of contents .

- ↑ The Kirschner . In: Johann Samuel Halle : Werkstätten der Gegenwart Künste , Berlin 1762, see p. 324 .

- ^ Fritz Hempe: Handbook for furriers . Verlag Kürschner-Zeitung Alexander Duncker, Leipzig 1932, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Paul Pabst: The tobacco shop . Inaugural dissertation to obtain a doctorate from the High Philosophical Faculty of the University of Leipzig, Berlin 1902, p. 85.

- ↑ a b Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods. XIX. Tape. Verlag Alexander Tuma, Vienna 1950, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Heinrich Hanicke: Handbook for furriers , publisher Alexander Duncker, Leipzig, 1895, p. 40

- ^ Christian Heinrich Schmidt: The furrier art . Verlag BF Voigt, Weimar 1844, p. 84.

- ↑ a b A. Wagner, Johannes Paeßler: Handbook for the entire tannery and leather industry . Deutscher Verlag Leipzig, 1925, pp. 863, 944.

- ↑ Alexander Tuma: Pelz-Lexikon. Fur and rough goods. XXI. Tape. Alexander Tuma publishing house, Vienna 1951. Keyword “Wirtschaftsgenossenschaft”.

- ↑ The whole song (and more)

- ↑ The winning song (sheet music) "We furriers, we are really happy people ..." .

- ↑ The whole song (and more)

- ^ Alfred Haverkamp, Elisabeth Müller-Luckner: Information, communication and self-presentation in medieval communities. In: Margarete Schindler (edit.): The older Buxtehude official statutes. In: Niederdeutsches Jahrbuch 75. (1952) 8-47, esp. On the noisy operations of the furriers. ; Mechthild Wiswe : furrier. In: Reinhold Reith (Hrsg.): Lexikon des alten Handwerks. From the late Middle Ages to the 20th century . Munich 1990, ISBN 3-486-56260-6 , pp. 134-139.

- ^ JG Krünitz: Oekonomische Encyklopädie , Volume 57: Kürschner - Kyrn , Brünn 1794, keyword Kürschner .

- ^ Mária Kresz: Popular Hungarian furrier work . Hsgr. Prof. Dr. Gyula Ortutay, Budapest 1979, ISBN 963-13-0419-1 , p. 72.

- ^ District museum in Syke, exhibition wing .

- ^ Heinrich Lange, Albert Regge: History of the dressers, furriers and cap makers in Germany . German Clothing Workers' Association (ed.), Berlin 1930, p. 219.

- ^ Wiener Pelz-Rundschau (eds.): Register of furriers, cap makers and others. Tobacco dyers in the fashion guild . Approx. 1936, p. 13 ( Supplementary agreement to the collective agreement (framework agreement) of June 12, 1933, § 2. Remuneration ).

- ↑ a b c Author collective: Manufacture of tobacco products and fur clothing . Fachbuchverlag Leipzig 1970, pp. 547-549.

- ↑ Business . In: German Kürschner magazine. Edition A, No. 10: Verlag Arthur Heber & Co, Berlin April 5, 1934, p. 298.

- ^ G. Trojan: On the origin of the fur knocking machines . In: "Der Rauchwarenmarkt" No. 13/14, Leipzig March 27, 1942, p. 9.

- ^ Fur tapping machine from Herpich, Berlin . In: Kürschner-Zeitung No. 25 of December 5, 1915. Verlag Axel Duncker, Berlin, title page back.

- ^ Walter Fellmann : The Leipziger Brühl . Fachbuchverlag, Leipzig 1989, p. 94.

- ^ Ing.Walter Hess, Leipzig: Modern fur knocking machines . In the fur trade. Volume VII / New Series No. 1, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin / Leipzig 1956, pp. 32–38.

- ↑ Kurt Nestler: The smoking goods refinement . Deutscher Verlag, Leipzig 1925, pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Heart-pounding machine . Data sheet from Pöhlandt, Württ. Pelzmaschinenfabrik, Murrhardt, for type HKM / 100. Undated.

- ↑ Max Nasse: America's fur industry - results of a study trip by German furriers and fur manufacturers. Berlin 1925, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Kurt Nestler: The smoking goods refinement . Deutscher Verlag, Leipzig, 1925, Appendix Fig. 10.

- ^ Advertisement in: Wiener Kürschner-Zeitung , Alexander Tuma, Vienna July 25, 1926, p. III.

- ^ Advertisements from J. Kulp, Rauchwaren, Munich, Arcostraße 14. In: Kürschner-Zeitung , Alexander Duncker, Leipzig, pp. 397, 434 (back of the magazine).

- ^ Advertisement from Carl Schrom, Borna Bez. Leipzig. In: Kürschner-Zeitung , Alexander Duncker, Leipzig, page 400c.

- ^ Advertisement from Carl Schrom: You have to see him work! In: America's fur industry - results of a study trip by German furriers and fur manufacturers . Berlin 1925, Reichsbund der Deutschen Kürschner, p. 142.

- ↑ Editor: New machines for tapping and cleaning. In: Der Rauchwarenmarkt No. 6, Leipzig September 12, 1931, p. 3.

- ↑ DHM general catalog , Dr. Hans Müller, Leipzig O 27, Holzhäuser Strasse 80, pp. 67-70. 1933.

- ^ Advertisement in Das Pelzgewerbe , Heft 5, Leipzig et al. 1955, p. 143.

- ↑ tapping machine . Data sheet from Rudolph Pöhlandt, Württ. Pelzmaschinenfabrik, undated (approx. Before 2000).