Little Foot

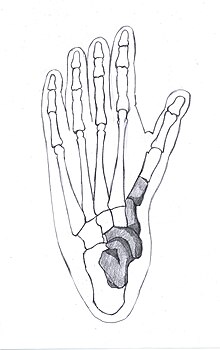

Little Foot describes the most complete skeleton of an early representative of the hominini that has been discovered to date . It was discovered in a limestone formation in Sterkfontein ( South Africa ) and is listed in the specialist publications as Australopithecus prometheus in the genus Australopithecus . The nickname "small foot" came about because four associated ankle bones were first described from this fossil in 1995. From the nature of these foot bones it was deduced that their owner was able to walk upright . However, the big toe could still be opposed .

The exposure and recovery of the bones turned out to be extremely difficult and time-consuming, as they were completely embedded in concrete-like hard breccia made of dolomite and radiolarite .

Find history

The four ankle bones were already collected in 1980 - undetected among numerous other mammalian bones - in a limestone cave (Silberberg Grotto) that had previously been industrially mined for decades , but were only superficially evaluated until 1994. Only after a large boulder containing an unusual accumulation of fossils was blasted off in this cave on the initiative of Phillip Tobias in 1992 , the fossils that had been recovered from the cave were carefully examined by Ronald J. Clarke . On September 6, 1994, he opened a box labeled Silberberg Grotto D 20 , which contained, among other things, a plastic bag labeled carnivore foot bones (the bones of predators). Clarke immediately identified one of these foot bones as a hominin, and as he continued to rummage through the collection, he came across three other hominin foot bones that were scientifically described the following year. Since the left ankle bone , the left scaphoid bone , the left sphenoid bone and the left metatarsal bone were recognized as belonging together, further unevaluated stocks were first sighted and in these eight more foot and hand bones were discovered by June 1997, which could possibly be ascribed to the same fossil . One of these bones - the fragment of a right tibia - had a relatively fresh fracture point, which could not have been formed until the 1920s at the earliest when blasted to mine limestone.

Then asked Clarke in early July 1997, two taxidermists of his institute, Stephen Motsumi and Nkwane Molefe, the original site where the fossils, 25 feet below the surface of the Silberberg Grotto to scan again. In fact, in this cave with the dimensions of a medium-sized church, the two discovered the counterpart to the already known fragment on July 3rd - after only two days of searching with the help of hand lamps. In the immediate vicinity of this right tibia fragment, the two taxidermists discovered the fragment of a left tibia protruding from the ground, the continuation of which was found among the fossils recovered from the cave years before, and a left fibula . Since the bones of both legs were in an anatomically correct arrangement, the taxidermists suspected that it could be a complete skeleton that had been embedded face down in the limestone.

In the months that followed, Clarke and his two assistants first exposed additional foot bones using a hammer and small chisels. Stephen Motsumi discovered the first remains of the upper body - a humerus - on September 11, 1998, and on September 17 the head of the individual finally became visible: a skull connected to the lower jaw, the left side of which faces up.

A year later, in July and August 1999, a left forearm and the corresponding left hand were discovered - again in an anatomically correct arrangement - and partially exposed. Clarke reported on this discovery six months later and explained that all previous analyzes indicated that the fossil corpse had apparently been completely displaced by terrain movements at most slightly and also not damaged by predators. In addition, narrow, former cavities were discovered in the area around the hand and wrist bones, which were filled with calcium carbonate . This suggests that the body was probably enveloped in rock deposits before it was completely decomposed.

Dating

Determining the age of the find turned out to be difficult and unsatisfactory as a result, as there are no volcanic layers in the area of the find that could be used to make a reliable absolute dating . Therefore, in July 1995 - on the basis of a relative dating using fossil monkey relatives and some carnivores - an estimated age of 3.0 to 3.5 million years was reported, which is why the fossil is described as the oldest find of a representative of the hominini in South Africa to date has been; this age attribution exactly matched the hominin footprints of Laetoli, which have been known since 1978 and are considered to be reliably dated . In a second analysis of the accompanying finds , however, this dating was already criticized as too old in March 1996 and instead named around 2.5 million years as the more likely age. A study in 2002 came to a similar conclusion, according to which Little Foot is "younger than 3 million years". A year later, however, an age of more than 4 million years was published based on the aluminum-beryllium method . At the end of 2006 a new study with the help of uranium-lead dating showed an age of 2.17 ± 0.17 million years. This dating was confirmed by a paleomagnetic analysis of the embedding layer package published in 2011 , which showed a minimum age of 2.2 million years and a maximum age of 2.58 million years. An earlier paleomagnetic dating of around 3.3 million years was based on a false assumption about the minimum age of the hanging layers. In 2014, however, it was argued again that the fossil was "at least 3 million years old", and in 2015 another aluminum-beryllium dating showed an age of 3.67 ± 0.16 million years. The dating is still controversial (as of August 2019).

Find description

In late 2008, Clarke published a reconstruction of the circumstances that made the fossil so unusually well preserved. In contrast to the other bones found in the same cave, were apparently swept over longer periods of time to their final storage location, the were in the vicinity Fund horizon of Littlefoot no other fossils, but rather in the underlying Fund horizons. The fossil also shows no damage from predators ; so it was not dragged into the cave as prey. Nevertheless, individual bones have broken, without this being attributable to the quarry work in the early 20th century. From these findings and from precise analyzes of the rock layers at the location of the fossil, Clarke concluded that the Australopithecus - like other animals before - must have fallen into the cave through a hole in the roof and perished there. A short time later, the hole was probably blocked by falling material, so that no more water could penetrate and wash away the bones of the carcass.

At the end of 2018, the first, more detailed find descriptions, which had already been announced for 2012, were published on an online platform of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory ; these articles had previously been peer-reviewed by the Journal of Human Evolution . According to this, Little Foot had significantly longer legs than arms and, if the dating to an age of 3.67 million years were to last, would be the oldest evidence of these characteristics characteristic of later species of hominini. This blueprint for the extremities, which differs from that of other great apes, also shows an early adaptation to the upright gait. According to the anatomical studies, a curvature of the left forearm indicates a fall injury during childhood.

In a detailed description of the skull, numerous features were identified that distinguish Little Foot from all other known species of the genus Australopithecus , which is why the provisional assignment of Little Foot to Australopithecus prometheus was confirmed in 2018 . The internal volume of the skull was - comparable to that of a chimpanzee living today - at least 408 cm 3 . From a three-dimensional, virtual reconstruction of the brain surface, it was deduced, among other things, that Little Foot still had a much larger visual cortex than later representatives of the hominini and that other areas of the brain surface were also more similar to the characteristics of the ancestors of chimpanzees living today than to those of the anatomically modern people.

From the relatively small size of the teeth it was deduced that Little Foot can be interpreted as a female individual. The height was 130 centimeters. The dentition could also be interpreted as an indication that Australopithecus prometheus lived mainly on plant-based food.

Way of life

In the first description of the four initially discovered bones of the foot, published in 1995, the authors had already explained that this Australopithecus was able to walk upright, but was also able to live in trees and with the help of grasping movements - thanks to the opposable toe - in to climb this around. The structure of the foot differs only slightly from that of a chimpanzee. Clarke saw this initial assessment confirmed by the additional foot bones discovered in 1998. The footprints of Australopithecus known from Laetoli and the arrangement of the foot bones discovered in the Silberberg Grotto show a high degree of similarity according to his find description. In his description of the fossil hand bones published in 1999, Clarke pointed out that both the length of the palm and the length of the individual finger bones were significantly shorter than those of chimpanzees and gorillas; the hand was called "relatively unspecialized" "like that of modern humans". With reference to predatory animal finds that lived in Africa at the time of the Australopithecines, Clarke shared the view of Jordi Sabater Pi, who argued in 1997 that staying on the ground at night was too dangerous for Australopithecus , so that he presumably - similar to the one today living chimpanzees and gorillas - built sleeping nests on trees. His physique also made it seem possible that Australopithecus stayed in trees during the day to look for food.

These interpretations were confirmed by an analysis of the dimensions and mobility of the first (uppermost) cervical vertebra , the atlas . According to a study published in 2020, its mobility was similar to that of a chimpanzee living today. In addition, a possible reconstruction of the blood flow to the brain based on the bone characteristics showed that Little Foot - also comparable to the chimpanzees - could only transport about a third of the amount of blood to the brain than an anatomically modern human.

Taxonomic classification

Initially, the find (archive number Stw 573) was not assigned to a specific species of the genus Australopithecus . In the first description of the find from July 1995 it said: "The bones probably belong to an early member of Australopithecus africanus or to another early species of hominid ". After part of the skull had been discovered and uncovered in 1998, Ron Clarke now pointed out that although the find was presumably to be assigned to the genus Australopithecus , its "unusual characteristics" did not match any of the Australopithecus species previously described .

It was not until the end of 2008 that Clarke finally made up his mind, described numerous deviations in characteristics between Little Foot on the one hand, Australopithecus africanus and Australopithecus afarensis on the other, and assigned the fossil to a second, previously unnamed species that lived in South Africa at the time, alongside Australopithecus africanus . At the same time, he took up the ideas of Robert Broom and Raymond Dart , who had already made various finds from Taung , Sterkfontein and Makapansgat (the “ Cradle of Humankind ”) for different species in the 1930s - for example, Australopithecus prometheus in 1948 ; later, however, the common name Australopithecus africanus prevailed internationally for these finds .

After the discovery of the around two million year old Australopithecus sediba , which was discovered in 2008 in the Malapa Cave just 15 km from Sterkfontein, it was suggested that Little Foot could have been an ancestor of Australopithecus sediba . Although a detailed description of Little Foot , on the basis of which the relationship to other species could be discussed professionally, was announced by Clarke for the end of 2012, but was not published, he ordered the find in 2015 for the second time Species Australopithecus prometheus , which existed parallel to Australopithecus africanus in South Africa. The assignment of fossils of the same age and similar to one another to different species is controversial between “rags and splinters” , since the natural variability of the species may be underestimated. The objection to the assignment of Stw 573 to Australopithecus prometheus was, for example, that this species was not delimited with sufficient precision from Australopithecus africanus in 1948 or ever thereafter (see noun nudum ), so that for this - formal - reason it is forbidden to use the species name for more recently discovered fossils to use unless a new holotype is introduced.

See also

literature

- Jörn Auf dem Kampe: The treasure of Sterkfontein. In: Geo. No. 6, 2011, pp. 78-92

- Ronald J. Clarke: Excavation, reconstruction and taphonomy of the StW 573 Australopithecus prometheus skeleton from Sterkfontein Caves, South Africa. In: Journal of Human Evolution. Volume 127, 2019, pp. 41-53, doi: 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2018.11.010

Web links

- Prehuman "Little Foot" out of the running? New dating makes Australopithecus skeleton more than a million years younger. On: scinexx.de from December 8, 2006

- “In the beginning a corpse.” Phillip Tobias on the discovery of the oldest pre-human skeleton in South Africa. On: spiegel.de of December 14, 1998

- Hominin v monkey deathmatch ended in a draw when they fell down a hole. On: newscientist.com from December 21, 2018

Individual evidence

- ^ Reiner Protsch von Zieten , Ronald J. Clarke : The oldest complete skeleton of an Australopithecus in Africa (StW 573). In: Anthropologischer Anzeiger. Volume 61, 2003, pp. 7-17

- ↑ The presentation of the find history follows a description by Donald Johanson in the editorial to the newsletter of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University from May 2005 and in the find description by Clarke from 1998 in the South African Journal of Science , Volume 94, p. 460 f.

- ↑ Ronald J. Clarke, Phillip Tobias : Sterkfontein member 2 foot bones of the oldest South African hominid. In: Science . Volume 269, 1995, pp. 521-524; doi : 10.1126 / science.7624772

- ↑ talkorigins.org : Fossil Hominids: Stw 573 (Little Foot)

- ↑ Ronald J. Clarke: First ever discovery of a well-preserved skull and associated skeleton of Australopithecus. In: South African Journal of Science. Volume 94, 1998, pp. 460-463

- ↑ Ronald J. Clarke: Discovery of the complete arm and hand of the 3.3 million-year-old Australopithecus skeleton from Sterkfontein. In: South African Journal of Science. Volume 95, 1999, pp. 477-480

- ↑ Michael Balter: Little Foot, Big Mystery. In: Science. Volume 333, No. 6048, 2011, p. 1374, doi : 10.1126 / science.333.6048.1374

- ↑ Jeffrey K. McKee of the South African Witwatersrand University in a technical commentary in Science , Volume 271, March 1, 1996, p. 1301

- ^ Lee R. Berger et al .: Revised age estimates of Australopithecus-bearing deposits at Sterkfontein, South Africa. In: American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Volume 119, No. 2, 2002, pp. 192-197; doi : 10.1002 / ajpa.10156

-

^ TC Partridge et al .: Lower Pliocene Hominid Remains from Sterkfontein. In: Science. Volume 300, 2003, pp. 607-612; doi : 10.1126 / science.1081651

spiegel.de of April 25, 2003: "Was the human cradle in South Africa?" - ^ Joanne Walker, Robert A. Cliff, Alfred G. Latham: U-Pb Isotopic Age of the StW 573 Hominid from Sterkfontein, South Africa. In: Science. Volume 314, 2006, pp. 1592-1594; doi : 10.1126 / science.1132916

- ↑ Andy IR Herries, John Shaw: Palaeomagnetic analysis of the Sterkfontein palaeocave deposits: Implications for the age of the hominin fossils and stone tool industries. In: Journal of Human Evolution. Volume 60, No. 5, 2011, pp. 523-539, doi : 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2010.09.001

- ↑ Timothy C. Partridge et al .: The new hominid skeleton from Sterkfontein, South Africa: age and preliminary assessment. In: Journal of Quaternary Science. Volume 14, 1999, pp. 293-298; Full text (PDF file; 679 kB)

-

↑ Laurent Bruxelles et al .: Stratigraphic analysis of the Sterkfontein StW 573 Australopithecus skeleton and implications for its age. In: Journal of Human Evolution. Volume 70, 2014, pp. 36–48, doi: 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2014.02.014 , full text

Michael Balter: 'Little Foot' Fossil Could Be Human Ancestor. In: news.sciencemag.org of March 14, 2014 -

↑ a b Darryl E. Granger et al .: New cosmogenic burial ages for Sterkfontein Member 2 Australopithecus and Member 5 Oldowan. In: Nature. Volume 522, No. 7554, 2015, pp. 85-88, doi: 10.1038 / nature14268

New cosmogenic burial ages for SA's Little Foot fossil and Oldowan artefacts. On: eurekalert.org from April 1, 2015 - ↑ Laurent Bruxelles et al .: A multiscale stratigraphic investigation of the context of StW 573 'Little Foot' and Member 2, Sterkfontein Caves, South Africa. In: Journal of Human Evolution. Volume 133, 2019, pp. 78-98, doi: 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2019.05.008

- ↑ Ron J. Clarke: Latest information on Sterkfontein's Australopithecus skeleton and a new look at Australopithecus. In: South African Journal of Science. Volume 104, 2008, pp. 443–449, full text (PDF)

- ^ Identity of Little Foot fossil stirs controversy. On: sciencemag.org of December 11, 2018

- ↑ Robin Huw Crompton et al .: Functional Anatomy, Biomechanical Performance Capabilities and Potential Niche of StW 573: an Australopithecus Skeleton (circa 3.67 Ma) From Sterkfontein Member 2, and its significance for The Last Common Ancestor of the African Apes and for Hominin Origins . In: bioRxiv. 2018, doi: 10.1101 / 481556

- ^ AJ Heile, Travis Rayne Pickering, Jason L. Heaton, and RJ Clarke: Bilateral Asymmetry of the Forearm Bones as Possible Evidence of Antemortem Trauma in the StW 573 Australopithecus Skeleton from Sterkfontein Member 2 (South Africa). In: bioRxiv. 2018, doi: 10.1101 / 486076

- ↑ Ronald J. Clarke and Kathleen Kuman: The skull of StW 573, a 3.67 Ma Australopithecus skeleton from Sterkfontein Caves, South Africa. In: bioRxiv. 2018, doi: 10.1101 / 483495 . Also published under the same title in: Journal of Human Evolution. Volume 134, September 2019, doi: 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2019.06.005

-

↑ Amélie Beaudet, Ronald J. Clarke, Edwin J. de Jager et al .: The endocast of StW 573 ("Little Foot") and hominin brain evolution. In: Journal of Human Evolution. Volume 126, 2019, pp. 112–123, doi: 10.1016 / j.jhevol.2018.11.009

Peering into Little Foot's 3.67 million-year-old brain. On: eurekalert.org from December 18, 2018 - ^ 'Little Foot' hominin emerges from stone after millions of years. On: nature.com from December 7, 2018

- ^ Controversial skeleton may be a new species of early human. On: newscientist.com from December 6, 2018

- ^ "Its foot has departed to only a small degree from that of the chimpanzee." Clarke and Tobias, in Science , Volume 269, 1995, p. 524

- ^ Jordi Sabater Pi et al .: Did the First Hominids Build Nests? In: Current Anthropology Vol. 38, No. 5, 1997, pp. 914-916; doi: 10.1086 / 204682

- ^ "I also think it probable that it spent parts of the day feeding in the trees, as do the orang-utans and chimpanzees." Clarke, South African Journal of Science , Volume 95, 1999, p. 480

- ↑ Amélie Beaudet, Ronald J. Clarke et al .: The atlas of StW 573 and the late emergence of human-like head mobility and brain metabolism. In: Scientific Reports. Volume 10, Article No. 4285, 2020, doi: 10.1038 / s41598-020-60837-2 .

- ^ "I prefer to reserve judgment on the fossil's exact taxonomic affinities, although it does appear to be a form of Australopithecus ". Quoted from Clarke, The first discovery of a well-preserved skull ... , p. 462

- ↑ Ron J. Clarke: Latest information on Sterkfontein's Australopithecus skeleton ... , p. 443

- ^ Raymond A. Dart: The Makapansgat proto-human Australopithecus prometheus. In: American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Volume 6, No. 3, 1948, pp. 259-283

- ↑ Michael Balter: Paleoanthropologist now rides high on a new fossil tide. In: Science. Volume 333, No. 6048, 2011, p. 1374, DOI: 10.1126 / science.333.6048.1373

- ↑ Tim White : Early Hominids - Diversity or Distortion? In: Science. Volume 299, No. 5615, 2003, pp. 1994-1997, doi: 10.1126 / science.1078294

- ↑ Lee R. Berger and John Hawks: Australopithecus prometheus is a nomen nudum. In: American Journal of Physical Anthropology. Advance online publication of December 14, 2018, doi: 10.1002 / ajpa.23743

- ↑ 'Little Foot' skeleton analysis reignites debate over the hominid's species. On: sciencenews.org from December 12, 2018