Man'yōshū

The Man'yōshū ( Japanese 萬 葉 集 or 万 葉 集 , Eng. "Collection of ten thousand leaves") is the first great Japanese poem anthology of the Wakas . It is a collection of 4,496 poems, including the Kokashū and the Ruijū Karin ( 類 聚 歌林 ). The Man'yōshū occupies a special position in the pre-classical literature of Japan ( Nara period ). In contrast to all subsequent collections of the Heian period, it was not compiled by imperial orders, but by private hands, primarily by the poet Ōtomo no Yakamochi based on the Chinese model, around 759 . The 20 volumes he created more or less by chance served as a model for the following imperial poetry collections.

The oldest poems can be dated back to the 4th century according to the traditional year counting, but most date from the period between 600 and 750.

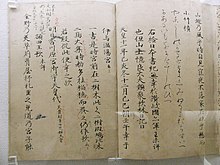

The compilation is in the Man'yōgaki , a syllable form consisting of Man'yōgana , in which Chinese characters are used to represent the pronunciation. The poems were recorded exclusively in Kanji , the Chinese characters adopted by the Japanese. These characters were used both ideographically and phonetically.

In the Man'yōshū 561 authors are named, including 70 women. In addition, a quarter of the poets remain anonymous, so that another 200 authors can be accepted. Among them were Ōtomo no Tabito (665–731), Yamanoue no Okura (660–733) and Kakinomoto no Hitomaro .

Title and structure

The title has always caused difficulties for translators. In particular, the second of the three ideograms in the title man-yō-shū can be understood differently. The character man ( 万 ) today generally means ten thousand , but it was also used to express an indefinitely large number, comparable to the term myriad . The character shū = collection is largely clear in its meaning. The ideogram yō has often been understood to mean leaf and has been expanded to Koto no ha , literally: word leaf ( 言葉 , kotoba ) in the sense of word, speech, poem. This view leads to what is probably the most common translation of the term “collection of ten thousand sheets”. The second ideogram is also understood to mean mansei , manyō many generations ( 葉 世 ). In this case the title was about poems from many generations .

The editors of the work are unknown, but the poet Ōtomo no Yakamochi may have contributed significantly to the creation of the collection. More than 561 poets are known by name, but about 25% of the poets who have contributed to the diversity of Man'yōshū have remained unknown. The oldest poems date back to the 4th century. Most of the poems in the anthology, however, date from the period between 600 and 750. The majority of the work are 4173 short poems Mijika-uta , the so-called tanka . In addition, the Man'yōshū contains 261 long poems Naga-uta or Chōka , and 61 expressly marked Sedōka , symmetrically structured six-line poems.

While the later imperial collections of poems followed a strict principle of structuring the content (spring, summer, autumn, winter, farewell, love, etc.), the arrangement of the poems in Man'yōshū is still largely disordered. The poems can be divided into six groups, which are distributed over the entire text corpus:

- Kusagusa no uta or Zōka ( 雑 歌 ) - mixed poems, such as congratulatory poems, travel songs and ballads.

- Sōmon ( 相 聞 ) - poems in mutual expression of a friendly feeling. An example of this is a poem that Nukada , the concubine of Emperor Tenji , wrote to the Emperor's younger brother, Prince Ōama, when he gave her to understand during a hunting trip that he was courting her.

- Banka ( 挽歌 ) - elegies , which include songs about the death of members of the imperial family.

- Hiyuka ( 譬 喩 歌 ) - allegorical poems

- Shiki kusagusa no uta or Eibutsuka ( 詠物 歌 ) - mixed poems with special consideration of nature and the four seasons

- Shiki Sōmon - mutual expressions taking into account the seasons

Emergence

As early as the beginning of the 10th century it was no longer possible to say by whom and when the Man'yōshū had been compiled. This was mainly due to the fact that the Tenno, and with them the court, turned to Chinese poetry again in the subsequent reigns up to the Engi period . It is therefore not possible to say with any certainty who the compilers of this extensive work were. What is certain is that the collection ended in the late Nara period .

According to the statements of the priest Keichū ( 契 沖 ), the Man'yōshū was created as a private collection of the poet Yakamochi from the Ōtomo clan, in contrast to the collections from twenty-one epochs , which were put together on imperial orders . He himself, involved in various political affairs, died under dubious circumstances in 785. The Ōtomo clan then disappeared completely by the end of the 9th century. The main sources of the Man'yōshū, the Kojiki and the Nihonshoki (also called Nihongi ) are mentioned in the anthology. Furthermore, works by individual poets, memoirs and diaries, but also orally transmitted poems served as sources. In some cases the original source or even the personal opinion of the compiler of the poem has been given. Another characteristic of Man'yōshū is the repetition of the poems in slightly modified versions.

Only Emperor Murakami dealt with the collection again. In the two centuries that had passed, it had largely been forgotten how to read the Chinese characters throughout. Murakami therefore set up a five-person commission, which began to record the reading in Cana . This notation of 951, known as Koten (“old reading”), was followed by the Jiten (“second reading”) of a six-person commission. The reading of 152 remaining poems was then worked out in the 13th century by the monk Sengaku ( Shinten , "new reading").

One of the most important source books of the Man'yōshū was the Ruijū Karin ( 類 聚 歌林 , "forest of arranged verses"), which was lost in later times. It was completed by Yamanoe Okura , one of the first Man'yōshū poets and an avid admirer of Chinese literature. Not much is known about the work, but it is believed that it served as a template for at least the first two volumes. Another source was the Kokashū ( 古 歌集 , "collection of old poems"). In addition, the Man'yōshū mentions the collections known as Hitomaro , Kanamura , Mushimaro and Sakimaro .

Usually a poem or a group of poems in Man'yōshū is preceded by the name of the author, a foreword and not infrequently a note. The foreword and note usually state the occasion, date and place, but also the source of the poem. All of this is written in Chinese . Even Chinese poetry, even if very rarely, appears in the books of Man'yōshū. The poems themselves are written in Chinese characters, the Kanji. It is noteworthy that the characters were mostly borrowed from Chinese because of their phonetic value, which is known as Manyōgana . In some cases the characters were also used semantically, with the corresponding Japanese reading ( ideographic use ). It was only from the Manyogana that the Kana, the Japanese syllabary, developed. Several kanji could have the same phonetic value. This posed a great challenge to the translation of the Man'yōshū.

Lyric forms

The poem (song) in Man'yōshū consists of several verses, which usually contain alternating five and seven moras . Originally it was probably written in lines of sixteen or seventeen characters.

Tanka

The most common form in the anthology that has survived to this day is the tanka . This form of poetry consists of five verses with 31 moras: 5/7/5/7/7.

Chōka

In addition, the so-called long poems or Chōka can be found in Man'yōshū . A chōka also consists of 5 or 7 moras per verse and ends with a seven-moor verse: 5/7/5/7/5… 7/7. The long poems are based on the Chinese model. They are often followed by short poems, so-called Kaeshi-uta or Hanka ( 反 歌 , repetition poem ). Formally, these are tanka, which in a concise form represent a summary or an addendum.

However, the longest chōka in the anthology does not exceed 150 verses. There are a total of 262 of the long poems in Man'yōshū, some of them from the pen of Kakinomoto Hitomaro , one of the most important poets. The Chōka itself lost importance in the 8th century, while the importance of the Tanka increased.

Sedōka

In addition to these two forms, there is also the "Kehrverslied" ( Sedōka ). It occurs 61 times in the collection of Ten Thousand Leaves. It is a combination of two half-poems , the kata-uta ( 片 歌 ), which is characterized by the double repetition of the triplet 5/7/7, i.e. 5/7/7/5/7/7. The Sedōka became less and less common over time and was eventually forgotten.

Bussokusekika

Finally, there is a special form, the Bussokusekika ( 仏 足 石 歌 , literally "Buddha footprint poems") with only one copy in Man'yōshū. It is reminiscent of a stone monument in the shape of the Buddha's footprint , which was built in 752 in the Yakushi Temple near Nara . It is engraved with 21 songs that have been preserved to this day. Six verses with 38 syllables are characteristic of this form: 5/7/5/7/7/7.

Rhetorical medium

Neither stresses, pitches, syllable lengths nor rhyme are used for the effect of the poem. This is attributed to the peculiarity of the Japanese language, in which every syllable ends with a vowel.

As a rhetorical device, alliterations were used on the one hand and the parallelism used in Chōka on the other . In addition, so-called kake kotoba ( 掛 詞 ) were used, word games with homonyms in which a reading can have different meanings depending on the characters. The Japanese word matsu can, for example , mean wait , but it can also mean jaw , depending on whether you use the character ( 待 つ ) or ( 松 ) as a basis. Another typical Japanese stylistic device is the Makura kotoba ( 枕 詞 ), called "pillow words" because they are semantically based on the reference word. In their function, they are comparable to the epitheta ornantia (decorative epithets). They are single words or sentences, generally with five syllables, which are linked in poems to other written words or phrases. Through the semantic overlay, the poet was able to create associations and sounds and thus give the poem ups and downs. Makura kotoba already appeared in Kojiki and Nihonshoki , but were only established in Man'yōshū by Kakinomoto Hitomaro.

The longer Joshi ( 序 詞 ), introductory words, have a similar structure to the pillow word, but longer than five moras and were mostly used as a form of the prologue .

Of the three means mentioned, kake kotoba is formally the simplest, but at the same time very important in Japanese poetry and a great challenge for translators.

Example: Book II, poem 1 by Iwa no hime:

| Kanbun | Japanese reading | Romaji | translation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

君 之 行 |

君 が 行 き |

Kimi ga yuki |

Your departure |

Yamatazu no here is Makura kotoba to mukae . The metric scheme is: 5-7-5-7-7.

content

In terms of quality, the Man'yōshū is by no means subject to any of the well-known Chinese collections and in terms of quantity it can be compared with the Greek anthology. In contrast to another important collection of poems, the Kokin Wakashū, the Man'yōshū contains both poetry of the court and those of the people in the country. The range even extends to Sakimori , the "seals of the border guards " and the seals of the eastern provinces, Azuma Uta , in their rough dialect. Alongside the splendid rendering of city life, vivid descriptions of rural life coexist. This anthology reflects the Japanese life at the time of its creation and clarifies contacts with Buddhism , Shintoism , Taoism and Confucianism .

The early works mainly include the creations of the imperial family , who have a preference for folk-song-like or ceremonial. A good example of this is the poem Yamato no kuni ("The Land of Yamato" ) attributed to the Emperor Yūryaku (456-479 ), which opens the Man'yōshū.

To the individual books

As already mentioned, the Man'yōshū consists of 20 volumes. It is believed that the first two books in the collection were put together on the orders of the emperor. Book I contains works from the period between the reign of Emperor Yūryaku (456–479) and the beginning of the Nara period. Book II, on the other hand, covers a longer period: it contains songs ascribed to the emperor Nintoku (313–399) and those dated to 715. Both books are rather less extensive compared to the other volumes, the poems appear in chronological order and are written in the so-called “early palace style”. Book III describes the period between the reign of Empress Suiko (592–628) and the year 744. Contrary to its predecessors, the book rather contains the seals of the lands. One can generally say that in the first three books of the Man'yōshū the poets of the Ōtomo clan are extraordinarily present. Book IV contains only Sōmonka from the Nara period. The key term in Book IV is koi . Probably the best translation of the term is “desire”, something that is never returned. The result is frustration that comes into its own.

Book V covers the years between 728 and 733 and contains some important chōka . Book VI is very similar to Books IV and VIII in terms of the time span and poets involved. It includes 27 chōka and some travel and banquet seals. Book VII as well as books X, XI and XII, equipped with anonymous poems, covers the period between the reign of Empress Jitō (686-696) and Empress Genshō (715-724). It contains several songs from the Hitomaro collection and includes another important part, 23 Sedōka . Books XI and XII can be assigned to the Fujiwara and early Nara periods. The poems in these books have a folk poetic character. Book IX reveals to us poems from the period between the reign of Emperor Jomei (629–641) and, with the exception of a tanka by Emperor Yūryaku, 744. The songs were largely obtained from the Hitomaro and Mushimaro collections. Book XIII has a unique repertoire of 67 Chōka , the majority of which is dated to the time of Kojiki and Nihonshoki . However, some specimens are clearly from the later periods. The collection of the poems of the eastern provinces can be found in Book XIV. Neither the authors nor the date of compilation is known, but there is a clear difference to the provincial poems in style and language. Book XV contains, among other things, a number of marine seals written by members of the Legation to Korea around 736 and some love poems dated 740 that were exchanged by Nakatomi Yakamori and his lover Sanu Chigami. The seals dealt with in Book XVI describe the period between the reign of Emperor Mommu (697–706) and the Tempyō era (729–749).

In general, the poet Ōtomo no Yakamochi is considered to be the compiler of the first 16 books of the Man'yōshū. It has also been proven that there is a time gap between Books I through XVI and the following four.

Books XVII to XX are regarded as personally collected works by Ōtomo no Yakamochi. Each of the four books belongs to the Nara period, book XVII covers the years 730 to 740, book XVIII 748 to 750 and book XIX 750 to 753. These three volumes contain a total of 47 Chōka , two thirds of the content of Book XIX is determined by Yakamochi's works, the majority of his masterpieces are located here. Book XX covers the years 753 to 759. The Sakamori , the songs of the border guards who guarded the coast of Kyushu , are written here. The name, rank, province, and status of each soldier are recorded along with their seal. The year 759, the last occurring date in the Man'yōshū, appended to the poem concluding the anthology, written by Yakamochi.

Outstanding poets

Kakinomoto no Hitomaro

From the middle of the 7th century a professional class of poets at court developed, where Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (around 662 to 710) played a not insignificant role. Nothing is known of his life, but he had a substantial part of 450 poems, 20 of them Chōka , in the Man'yōshū. The poems he has created can be divided into two categories: those that he made to order, so to speak, in his function as court poet, and those that he created out of his personal feelings. The former include elegies on the death of members of the imperial family. Especially in the Chōka he showed all his artistic skills. By using joshi and makura kotoba , accompanied by refrain-like repetitions, he knew how to shape the sound of the poem. The long poem found its climax as well as its end with Hitomaro. The court poet Yamabe no Akahito tried to continue the tradition of Chōka , but did not succeed in reaching the masterpiece of Hitomaro. For the sinking of the Choka there were several reasons. The Chōka knew only a few stylistic means, such as the design with 5 and 7 syllables. As mentioned earlier, rhymes or accents did not matter, contrary to the European poem. Furthermore, the long poems were praises to the emperor, with only a few exceptions. So the seals were by no means designed in a variety of ways. In the end, Hitomaro's poems did not embody an ideal, but merely expressed an absolutely loyal attitude towards the “Great Ruler”.

The second group of his poems, Personal Sentiments, presents him as an excellent poet, especially in relation to the elegies he wrote on the death of his wife.

Yamabe no Akahito

The central themes of Man'yōshū were love and pain over death. The poems dealing with this drew their metaphors from the immediate natural environment, whereby the feeling of love was expressed through flowers, birds, moon and wind, the pain, on the other hand, made use of metaphors such as mountains, rivers, grass and trees. There was no doubt that there was a special affinity with the changing of the seasons. However, the concept of nature was not dealt with in its full range. It so happened that, for example, the moon served as the motif in many poems, while the sun and stars, on the other hand, were seldom featured in poetry. Furthermore, the sea near the coast was preferred to the vastness of the sea.

The poet Yamabe no Akahito , known for his landscape poems, wrote his poems, in contrast to Hitomaro, even when there was no special reason to do so. The subjects of his poems were not huge mountains, but the Kaguyama, a hill 148 meters high, not the sea, but the small bays with their fishing boats.

Because Akahito only created natural poetry and in no way developed further in this direction, he inevitably became a specialist in natural poetry. He discovered that poetry was also possible without intuition and originality. So he became the first professional poet of Japanese poetry, which describes his historical significance.

Yamanoue no Okura

Another poet played an important role in Man'yōshū: Yamanoue no Okura . Nothing is known about his origin, but the Nihonshoki reports that a "Yamanoue no Okura, without court rank" was a member of the embassy to China in 701. After three years of residence he returned to Japan and was raised to the nobility in 714. In 721 he became the Crown Prince's teacher. 726 he was sent to Kyushu as governor of Chikuzen . Several years later he fell ill and wrote in 733 a "text, to comfort oneself in the face of long suffering", in which he described the symptoms of his illness.

During his stay in China, Okura perfected his ability to write Chinese texts that reveal a strong Taoist and Buddhist influence. For example, in the preface to one of his poems, "Correction of a Stray Spirit" (V / 800), he quotes the Sankō and the Gokyō , essential Confucian terms. Another poem that he wrote, an elegy on the death of his wife (V / 794) shows massive Buddhist influences.

Okura's love for family and children was a major theme in his poems. His poem “Song when leaving a banquet”, mentioned above, was authoritative, because no one but himself has ever written such verses again. Since the Edo period , it was even considered shameful for a man to leave a banquet for family reasons. A second theme of his poems was the burden of old age. Accompanying this was his “Poem about the difficulty of living in this world”, in which he complains about the imminent old age .

Okura's third major subject area includes poems about misery, poverty and the heartlessness of the tax collector. The following poem, a counter-verse to the Chōka Dialogue on Poverty (V / 892), makes his thoughts clear:

-

Life is bitter and miserable to me.

Can't fly away,

I'm not a bird. - (V / 853)

This topic was never touched on again by any of his contemporaries or successors.

Ōtomo no Yakamochi

The son of Ōtomo no Tabito , Yakamochi (718? –785) spent his youth in Kyūshū. After his father died, he became head of the house of Ōtomo. His political career was not unsuccessful: he served as governor of various provinces, but also often stayed at the court in Nara. In 756 he was involved in an unsuccessful plot against the Fujiwara , who were influential at the court , which made the star of his political career sink.

Ōtomo no Yakamochi is one of the main compilers of the Man'yōshū, which contains around 500 poems by him, the last from the year 759. His merit lies neither in the originality, nor in the language or the sensitivity of his poems, he is more in the fact that Yakamochi managed the expression of natural feeling to refine and thus to the world of Kokinshu if not (to 905) even to that of the Shin-Kokinshu be reconciled (to 1205).

The court and folk poetry

On the one hand, the poetry of the aristocracy of the 7th century regarded the long poem as a representative form of poetry and used it primarily on special and collective occasions. On the other hand, the lyrical poem developed in the tanka , the short poem, which became the outlet for personal feelings. The recurring motif of the tanka was the love between man and woman, evidenced by metaphors from the natural environment. Despite the fact that the takeover of the mainland culture had already begun, the Chinese thought could not yet penetrate the deep layers of thought. Even during the heyday of Buddhist art in the Tempyō era (729-749), Buddhist thoughts did not manifest themselves in the poetry of the nobility. "The poets of the 8th century described nature detached from human concerns (Yamabe no Akahito), traced the psychological distortions of love ( Ōtomo no Sakanoue ), or sang about the nuances of a highly refined world of sensation (Ōtomo no Yakamochi)". Love remained the central theme of the poetry and the poets of the court set the intense experience of the moment as the highest commandment.

Sakimori Uta

Representative of the folk poetry were on the one hand Sakimori Uta ( 防 人 歌 ), songs of the border guards ( sakimori ) and on the other hand Azuma Uta ( 東 歌 ), songs of the eastern provinces. The content of the Sakimori Uta , with 80 songs in the Man'yōshū, was made up of three main themes. About a third of the songs complain about the separation from the wife or lover, another third is for the parents or the mother (only in one case the father) at home and only the rest is concerned with the actual service of the soldiers. The latter, however, are by no means praises to the military service, the soldiers often complain hatefully about their work:

- What a mean guy!

To make

myself a border guard , because I was lying sick. - (XX / 4382)

There was a hierarchy among the border guards: there was one sub-group leader for every 10 soldiers. In contrast to the common soldier, the sub-group leaders sometimes passed on completely different types of songs:

- From that moment on

I don't

want to look back, I want to go out

to serve my master

as his most humble shield. - (XX / 4373)

Azuma Uta

The emotional feelings of the people in the country were not fundamentally different from those of the court. One thing they had in common, for example, was the common Japanese worldview. This is evidenced by the Azuma Uta , over 230 short poems by anonymous poets from the provinces. It is believed that these originated in the 8th century. Almost no features of Buddhism are contained in the Azuma Uta , which means that one can assume that the original Japanese culture as it was still preserved at the time is reflected here.

As in the poetry of the court, the love between man and woman is the central motif here too. 196 of the over 230 poems are assigned to the group of Sōmonka by the compilers , but among the remaining there are some that more or less directly address the subject of love. Contrary to the poets of the court, there is hardly any natural poetry that is detached from a feeling of love. Only 2 poems mention death. The description of love between a man and a woman shows only a few verbs, which are correspondingly frequent. These can be divided into two groups: those who relate to direct physical contact and those who deal with the psychological side of love. One of the first is nu , for example , to sleep in the sense of cohabitation. The other group includes verbs like kofu , to love, or mofu , to yearn. Azuma Uta reflects the popular belief that tries to determine the near future, even to influence it, by means of oracles, the interpretation of words of passers-by and the burning of the shoulder blade bones of a deer.

See also

literature

- The literatures of the East in individual representations . Volume X. History of Japanese Literature by Karl Florenz , Leipzig, CF Amelangs Verlag, 1909.

- Katō Shūichi : A history of Japanese Literature. Vol.1, Kodansha International, Tokyo, New York, London, 1981 ISBN 0-87011-491-3

- Frederick Victor Dickins: Primitive & Mediaeval Japanese Texts . Translated into English with Introductions Notes and Glossaries. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1906 ( digitized in the Internet Archive - annotated, English translation of the Man'yōshū and the Taketori Monogatari ).

- Frederick Victor Dickins: Primitive & Mediaeval Japanese Texts . Transliterated into Roman with Introductions Notes and Glossaries. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1906 ( digitized version in the Internet Archive - transliteration of the Man'yōshū and other works including a detailed description of the Makura-Kotoba used).

- Alfred Lorenzen: Hitomaro's poems from the Man'yōshū in text and translation with explanations . Commission publisher L. Friederichsen & Co., Hamburg 1927.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: Old Japanese memory poetry - landscape, writing and cultural memory in Man'yōshū (萬 葉 集) . Volume 1: Prolegomenon: Landscape in the Process of Becoming the Waka Poetry. Volume 2: Writing games and memorial poetry . Ergon, Würzburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-95650-009-1 .

Web links

- Motosawa Masafumi: "Man'yōshū" . In: Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugaku-in , March 28, 2007 (English)

- Annotated copy of Man'yōshū in the version ( bon ) of Nishi Hongan-ji (Japanese)

swell

- Graeme Wilson (transl.): From The Morning Of The World . Harvill Publishing House, London 1991

- Ian Hideo Levy (translator): The Ten Thousand Leaves: A Translation of the Man'yōshū, Japan's Premier Anthology of Classical Poetry . Princeton University Press, New Jersey 1987 (first edition 1981)

- Donald Keene: Seeds In The Heart . Columbia University Press, New York 1999

- JLPierson (translator): The Manyōśū. Translated and Annotated, Book 1 . Late EJBrill LTD, Leyden 1929

- Theodore De Bary: Manyōshū . Columbia University Press, New York 1969

- Shūichi Katō: The Japanese literary history . Scherz Verlag, Bern [u. a.] 1990

- Horst Hammitzsch (Ed.): Japan Handbook . Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1990

Remarks

- ↑ These are the first four tanka of the second book, written by Iwa no hime , wife of Emperor Nintoku (traditional reign: 313-399).

- ↑ Karl Florenz notes that this use could have been used for the first time in the preface to the Kokinshū at the beginning of the 10th century, which means that this interpretation would be lost.

- ↑ Florence names six groups, Katō Shūichi, however, three groups: Zōka, Sōmonka and Banka. History of Japanese Literature, p. 59.

- ↑ According to information from the Eiga - ( 栄 花 物語 ) and Yotsugi - Monogatari ( 栄 華 物語 ), Tachibana no Moroe ( 橘 諸兄 ) and some dignitaries were the compilers of Man'yōshū. However, it is doubtful whether this information is reliable, since on the one hand the sources date from the 11th century and on the other hand the compilation continued after Tachibana's death in 757.

- ↑ It is the 31-volume commentary Manyō-Daishōki ( 万 葉 代 匠 記 ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ History of Japanese Literature, p. 80.

- ↑ 契 沖 . In: デ ジ タ ル 版 日本人 名 大 辞典 + Plus at kotobank.jp. Kodansha, accessed November 20, 2011 (Japanese).

- ↑ Florence: History of Japanese Literature, p. 81.

- ↑ 類 聚 歌林 . In: デ ジ タ ル 版 日本人 名 大 辞典 + Plus at kotobank.jp. Kodansha, accessed November 20, 2011 (Japanese).

- ↑ Annotated copy of the Man'yōshū ( Memento of the original from April 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Translation by Karl Florenz, History of Japanese Literature, p. 78.