Military coup in South Vietnam in 1960

| date | November 11, 1960 |

|---|---|

| place | Saigon |

| output | Failure of the coup |

| consequences | Opponents of the Diệm regime were imprisoned and some of them were sentenced to death |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Rebels of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam |

Army loyalists of the Republic of Vietnam |

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| an armored regiment, 3 paratrooper battalions and a marine battalion | 5th and 7th Divisions of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam |

| losses | |

| not exactly known, more than 400 dead on both sides | |

The military coup in South Vietnam on November 11, 1960 was an attempted coup by rebelling soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) against the then President of South Vietnam Ngô Đình Diệm . It was led by officers from the Vietnamese Airborne Division, Lieutenant Colonel Vuong Van Dong and Colonel Nguyen Chanh Thi.

The revolt against the president was based on his authoritarian style of government, which his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu and his wife Madame Ngo Dinh Nhu had a major influence. The coup failed because it was poorly organized and the president had enough time to call on loyal forces to help. Most of the leaders managed to flee to Cambodia after the coup attempt , while the remaining conspirators were tried in 1963.

backgrounds

Diệm's takeover

Against the colonial masters of French Indochina minded Viet Minh under Ho Chi Minh won since 1945 in Vietnam increasing influence. After the communist seizure of power by the August Revolution , Diệm refused to join the government of Ho Chi Minh in his role as minister and went into exile in the United States. As an anti-communist and anti-colonialist Vietnamese nationalist, Diệm was able to establish good contacts with influential politicians. After the end of the Indochina War and the withdrawal of French troops in 1954, these politicians were able to convince the American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles to appoint Diệm as Prime Minister. Through a manipulated election, Diệm made himself president in 1955 and abolished the monarchy under the unpopular Emperor Bảo Đại , who refused all-Vietnamese elections, which is why the division of Vietnam into the communist north and the capitalist south along the 17th parallel to the, as agreed in the Indochina conference Former Prime Minister Diệm came to power.

Further development of Diệm's style of government

The president then further consolidated his position of power by founding two secret services that spied on each other and by filling influential positions with close relatives. After taking office, Diệm took brutal action against communists and other supposed or actual political opponents. Independent estimates suggest that between 1955 and 1957 around 150,000 people were imprisoned and 12,000 people executed. By rejecting a land reform deemed necessary by the USA , forced relocation of the rural population and a Catholic conversion campaign, according to which all South Vietnamese were to convert to the Roman Catholic faith , the president turned all major political groups against him. He countered opposition efforts with arrests and executions. Since the partition, the rivalry between the north and the south has grown stronger. In 1959, communists were again sent to South Vietnam, who in 1960 founded the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NFL), which carried out armed actions in South Vietnam as a resistance group.

Causes and preparations

The coup was led by Lieutenant Colonel Vuong Van Dong, 28, who served in the ARVN Parachute Brigade. Dong was very dissatisfied with Diệm's authoritarian style of government and its constant interference in military matters.

The putschist's brother-in-law, Lieutenant Colonel Nguyen Trieu Hong, head of the training department at the General Staff Academy, supported Dong together with his uncle Hoang Co Thuy. He was a wealthy Saigon lawyer and had been a political activist since World War II .

Many ARVN officers were members of other anti-communist groups that had taken opposition to Diệm. Examples of such opposition groups are the Dai Viet Quoc Dan Dang (Nationalist Party of Greater Vietnam) and the Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang (VNQDD - Nationalist Party of Vietnam), both of which arose before World War II . With the help of its Chinese allies, the Kuomintang , the VNQDD had run a military academy near the Chinese border. Diệm and his family clan, however, had smashed all anti-communist nationalist alternatives and his politicization of the army had alienated them from him. Diệm promoted officers more on the basis of loyalty than military ability and played high-ranking officers off against one another in order to prevent a challenge to his rule by weakening the management level. As a result, officers loyal to Diệm who belonged to the secret, Catholic-dominated Can-Lao party that Diệm installed to control South Vietnamese society were rewarded with promotions.

Dong's preparations to recruit disgruntled officers for the coup lasted more than a year. Among the revolting officers was Dong's commander, Colonel Nguyen Chanh Thi , who had fought for Diệm against the organized criminal group Bình Xuyên in the Battle of Saigon in 1955. His performance had impressed the eternal bachelor and dictator Dim so much that he referred to Thi as his son from now on. The Americans who worked with him were less impressed. The CIA described him as an "opportunist with no real convictions", while a US military adviser described Thi as "robust, unscrupulous and fearless, but stupid".

A few months before the coup, Dong and Diệm's brother and advisor Ngo Dinh Nhu , who was widely seen as the head of the regime, met. He asked Nhu for the depoliticization of the army and reforms. At the end of the conversation, Dong announced that the process had been positive and that there was definitely hope for improvement. A few weeks later, however, Dong and the other collaborators were transferred to different units and thus physically separated. Fearing that Diệm and his brother would try to thwart the coup plans, the coup planners accelerated their plans and set the date of the coup for October 6th. A postponement of the date became necessary, however, as the rebels were drafted to take part in the fighting against the communists near Kontum in the central highlands under the command of the II Corps of the ARVN.

The coup was organized with the help of VNQDD and Dai Viet members, including civilians and officers. Dong was able to win a tank regiment, a naval unit and three paratrooper battalions for support. The operation was scheduled to start on November 11th at 11:00 a.m. However, the paratroopers were not properly informed of their officers' plans, as they were told that they would be sent off-site to attack the Viet Cong . After the soldiers started moving, the officers claimed that the President's Guard mutinied against Diệm.

Coup

In the early morning of November 11th, three paratrooper battalions of the ARVN parachute brigade boarded armored vehicles.

The coup plotters had placed all generals stationed in Saigon under house arrest, which meant Diệm's support had to come from outside the city. Among the planned imprisoned generals should also be the chief of staff of the ARVN, but the conspirators did not know that he had moved to another house and that Diệm could later come to help.

Although the rebels had already taken the headquarters of the Vietnamese General Staff in the Tân Sơn Nhứt Air Force Base , they failed to block the roads to Saigon. Nor could they prevent Diệm from calling loyal units to help over the palace telephone lines. The renegade paratroopers advanced along the main road from Saigon to the Independence Palace. The rebels surrounded the area and initially decided against a direct attack, believing that Diệm would yield to their demands. The leader of the insurgents, Lieutenant Colonel Dong, tried to win the local US ambassador Elbridge Durbrow to put pressure on Diệm. Despite his own critical stance on Diệm and his policies, Durbrow explained the position of the American government under the containment policy , which tried to contain communism by every available means, with the words: "We support this government until it fails."

A high wall, a fence and a few guard posts surrounded the palace grounds and the garden. The mutinous paratroopers got out and positioned themselves to attack the main gate. Some rebels charged forward, others opened heavy fire on the front of the palace. Diệm was almost killed during the first volleys when a rebel machine gun projectile from the adjoining Palace of Justice broke through Dim's bedroom window and hit the bed of the President, who had just got up.

The first onslaught of parachute soldiers met surprisingly strong resistance. There were only around 30 to 60 presidential guards between Diệm and the insurgents, with the defenders able to repel the first advance. Seven rebels were killed in the process. They tried to climb over the walls to get to the palace. The coup plotters cordoned off the square and continued firing. Vehicles with reinforcements arrived and the attack resumed at 7:30 a.m. The Presidential Guard, however, continued their bitter resistance. Half an hour later, five rebel armored vehicles circled the palace. They fired at the security posts and shot at the palace complex with mortars . The firefights subsided around 10:30 a.m. Meanwhile, the rebels had taken the national police bases, Saigon Radio and the barracks of the Presidential Guard. However, the rebels also suffered a setback when Lieutenant Colonel Hong, brother-in-law of the conspirator Dong, was killed in the skirmishes over the police station. He was sitting behind the front line in his jeep when he was hit by a ricochet .

Meanwhile, Diệm went to his brother and advisor Ngô Đình Nhu and his wife Madame Ngo Dinh Nhu in the cellar . Brigadier General Nguyễn Khánh , then Chief of the General Staff of the ARVN, climbed over the palace wall to reach Diệm during the siege. Khanh was living in the city center near the Independence Palace at the time and was awakened by the exchange of fire. After his arrival at the presidential palace, the chief of staff set about coordinating the action of the loyalists and defenders together with the deputy director of the civil guard, Ky Quan Liem.

At dawn, civilians advocating overthrowing the regime gathered at the gates of the Independence Palace and used banners to encourage the rebels. Radio Saigon reported that a "revolutionary council" had taken over government in South Vietnam. Diệm appeared lost, while many soldiers stationed in Saigon joined the insurgents. According to Nguyen Thai Binh, a political rival of Diệm who had to go into exile, "anyone but him would have surrendered." However, the rebels hesitated when they decided their next move.

Dong pleaded for the use of the possibility of a storm on the palace and the capture of Diệm. Thi, on the other hand, was concerned that Diệm might die in an attack. He considered the President, despite his shortcomings, to be the best leader available in South Vietnam and believed that forced reform would be the best outcome. What all rebels had in common, however, was the call for Diệm's brother and his wife to withdraw from the government, although they disagreed on whether to execute or deport them.

Thi demanded that Diệm appoint an officer as Prime Minister and have Madame Nhu removed from the palace. Saigon Radio broadcast a speech, approved by This Revolutionary Council, claiming that Diệm would be ousted for corruption and suppression of freedom. Concerned about the uprising, Diệm sent his private secretary Vo Van Hai to negotiate with the leaders of the insurgents. In the afternoon, the ARVN chief of staff, Khanh, left the Independence Palace to meet the rebel officers and respond to their demands. The rebel negotiators were Lieutenant Colonel Dong and Major Nguyen Huy Loi .

The coup plotters unilaterally named Brigadier General Le Van Kim , head of the Vietnamese National Military Academy, the country's primary officers' school in Da Lat , as the new prime minister. Kim was not a Can Lao member and was later placed under house arrest when Diệm regained control. They also suggested that Diệm appoint the chief of the armed forces, General Lê Văn Tỵ , as defense minister. Diệm asked Ty, who had been put under house arrest by the masterminds of the coup, if he would agree to do so, but Ty refused.

Phan Quang Dan joined the rebels and acted as their spokesman. As Diệm's most prominent critic, Dan was subsequently excluded from the 1959 parliamentary elections after winning his seat 6-1, despite Di organisiertm organizing vote-buying against him. He cited political mismanagement of the war against the Viet Cong and the government's refusal to broaden its political base as the reasons for the revolt. Dan spoke on Radio Vietnam and held a press conference. In the meantime, Thuy began to organize a coalition of political parties that would take power after Diệm's fall. He had already brought the VNQDD, the Dai Viet and the religious movements Hoa Hao and Cao Dai behind him and was looking for further supporters.

Khanh returned to the palace and reported the results of his discussion with the rebels to the Ngos. He suggested that Diệm resign because of the demands of the rebels and the protesters gathered outside the palace. Madame Nhu opposed Diệm's willingness to agree to a power-sharing agreement, calling it providence for Diệm and his family to save the country. Madame Nhu's aggressive demeanor and her constant calls for Khanh to attack prompted the general to threaten to leave the palace. Diệm had to tell his sister-in-law to remain silent so that Khanh could stay with the president.

During the stalemate, Durbrow stated ambiguously that the US “believed it was of paramount importance to Vietnam and the Free World that an agreement be reached as soon as possible to avoid further division and bloodshed, which fatally undermines capability Vietnam would mean resisting the communists. ”American officials secretly urged both sides to come to a peaceful power-sharing agreement.

Meanwhile, the ongoing negotiations allowed the Loyalists to bring troops to Saigon. Khanh used the communications links he had left to inform high-ranking officers outside of Saigon. The 5th Division, under the command of the future President, Colonel Nguyen Van Thieu , set infantry forces in motion from Biên Hòa . The 7th Division under Colonel Tran Thien Khiem put tanks from the 2nd Tank Battalion in Mỹ Tho , a town in the Mekong Delta south of Saigon, on the march. Khanh also convinced Le Nguyen Khang , the Commander in Chief of the Marine Corps, to deploy the 1st and 2nd Marine Battalions. Deputy Secretary of Defense Nguyen Dinh Thuan called Durbrow and asked about his position in the upcoming clash between rebels and loyalists. Durbrow said, “I hope that the Revolutionary Committee and President Diệm can come together and agree to work together, as civil war can only benefit the communists. If one side or the other has to make concessions in order to reach an agreement, I think it would be desirable to reach agreement with the communists. ”Durbrow was concerned that if he preferred one side over the other and lost that side, that United States would have to cooperate with a hostile regime.

Diệm instructed Khanh to continue negotiations with the paratroopers and seek rapprochement. After agreeing to open formal negotiations, both sides agreed to a ceasefire. In the meantime, loyalist troops continued to advance towards the capital while the rebels reported Dim's surrender on the radio, apparently to attract more troops to their cause. Diệm promised to abolish press censorship, liberalize the economy and hold free and equal elections. He refused to fire Nhu, but agreed to dissolve his cabinet and form a new government that included members of the Revolutionary Council. In the early morning hours of November 12, Diệm recorded a speech in which he listed his concessions and which the rebels later had broadcast on Radio Saigon.

As the speech was being broadcast, the two infantry divisions and supporting armored units were approaching the palace. Some of the Saigon-based units that had joined the rebels, convinced that Diệm had regained the upper hand, switched sides for the second time in 48 hours. The paratroopers were outnumbered and forced to retreat to defensive positions around their headquarters, a quickly built camp in a public park about a kilometer from the palace. After a short but violent skirmish in which around 400 people died, the rebellion was crushed. Large numbers of civilians who had participated in protests against Diệm in front of the palace were among the dead. Thi had got them to attempt to storm the palace, and 13 of them were shot while climbing over the walls. The other civilians then fled.

consequences

After the failed coup, Dong, Thi and a few other high-ranking officers of the coup leaders escaped to Tan Son Nhut and boarded a waiting C-47 with which they flew to Cambodia . Prince Sihanouk granted them asylum there .

Diệm immediately withdrew his promises and had dozens of his critics arrested, including several former ministers and some of the 18 members of the Caravelle group who had written openly calling for reform. One of Diệm's first orders after order was restored was the arrest of Dan, who was imprisoned and tortured.

In the post-coup period, Diệm blamed Durbrow for what he saw as insufficient support from the United States, while his brother Nhu also accused the ambassador of having secretly conspired with the coup plotters . Durbrow dismissed this, saying that he was “100% behind Diệm.” In May 1961, Nhu said, “The least one can say [...] that the State Department is between a befriended government and a group of rebels that run that government wanted to resign, behaved neutrally [...] and that the official attitude of the Americans during the coup was by no means the attitude the president would have expected. ”Durbrow asked Diệm to treat the rest of the rebel leaders indulgently and emphasized the need to him "To unite all elements [of political opinion] of the country." However, Di jedochm categorically refused and angrily rejected the ambassador's statements.

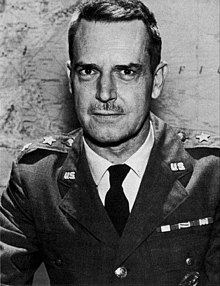

The American military establishment strongly supported Diệm. Colonel Edward Lansdale , a CIA agent who helped Diệm come to power in 1955, poked fun at Durbrow's remarks and called on the Eisenhower administration to recall the ambassador. Lansdale said it was “highly doubtful that Ambassador Durbrow has any personal influence left. Diệm has to believe that Durbrow sympathized with the rebels. Perhaps he thinks Durbrow's remarks over the months helped spark the revolt. ”Lieutenant General Lionel McGarr , the new commander of the Military Assistance Advisory Group , agreed with Lansdale. McGarr had been associated with both rebel and loyalist units during the stalemate and attributed the crackdown on the coup to "Diệm's courageous actions combined with the loyalty and versatility of the commanders who had led their troops to Saigon." McGarr went on to state that "Diệm [...] emerged from this difficult trial in a position of greater strength and with visible evidence of strong support in both the armed forces and civilians." General Lyman Lemnitzer , Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff said, “When you have insurgent forces against you, you have to act with strength and not restrict your friends. The important point is that sometimes bloodshed cannot be avoided and that whoever is in power must act decisively. "

Diệm later accused two Americans, George Carver and Russ Miller, of being involved in the plot. Both had stayed with the rebel officers during the coup attempt. Durbrow had sent them there to keep the situation under observation, but Diệm thought they should have encouraged the insurgents. It later emerged that Carver had been on friendly terms with the leaders of the coup and had arranged for Thuys to be evacuated from South Vietnam after its suppression. The Ngo brothers informed the Americans that they wanted Carver to be deported, and a little later he received a death threat. This was reportedly signed by the coup plotters, who were angry that Carver had let them down and the Americans withdrew their support for them. The Americans suspected Nhu of drafting the threat, but promised the Ngos that Carver would be removed from the country for his own safety, allowing all sides to save face.

The rift between American diplomatic and military representatives in South Vietnam began to widen. At the same time, Durbrow continued his policy of urging Diệm to liberalize his regime. Durbrow saw the coup as a sign that Diệm was unpopular, and since the president allowed only insignificant changes, he signaled to Washington that it might be necessary to remove him.

These tensions were also reflected in the relationship between the ARVN and Diệm. The paratroopers had been considered the most loyal of the ARVN units, so Diệm intensified his practice of being promoted by loyalty rather than skill. Khiem was promoted to general and appointed chief of staff of the army. The Ngo brothers suspected Khanh for getting through the rebel lines too easily. Khanh's actions earned him a reputation for helping the president, but he was later criticized for sympathizing with both camps. The critics pointed out that Khanh had taken a positive view of the coup plotters and only decided against the rebels when Diệm's victory became apparent. Khanh was later transferred to the central highlands as commander of the II Corps . General Duong Van Minh , who did not come to Diệm's aid during the siege and instead stayed at home, was demoted. During the uprising, the putschists nominated Minh as a candidate for the post of defense minister. After Diệm contacted him, Minh declined the offer. The reason given by Minh was that although he would like to fight for Diệm on the battlefield, he was neither interested in nor suitable for politics. But since Minh had done nothing to support the president, he was deported to the post of Supreme Military Advisor, where he had neither influence nor troops. This measure was also intended to minimize the risk of the coup being repeated.

process

The trial of the accused putschists took place in mid-1963, more than two years after the events. Diệm set the hearings in the midst of the Buddhist crisis , which was interpreted as an attempt to deter the population from further expressions of displeasure. 19 officers and 34 civilians were accused of being involved in the coup and were summoned to the special military tribunal .

Diệm’s representatives gave the Americans a slightly veiled warning not to interfere. The chief prosecutor said he had documents proving a foreign power's support for the coup, but said he could not publicly expose that nation. It later emerged in secret negotiations that he was directly accusing two Americans: George Carver, an employee of the United States Operations Mission , who later turned out to be a CIA agent, and Howard C. Elting, who was deputy head of the American embassy in Saigon was described.

One of the prominent civilians summoned to the military tribunal was a well-known writer who wrote under the pen name Nhat Linh . It was the leader of the VNQDD, Nguyen Tuong Tam , who briefly served as Ho Chi Minh's foreign minister in 1946 . Tam had given up his post when he was supposed to lead the Vietnamese delegation to the Fontainebleau Conference and negotiate concessions to the Union française there . In the 30 months since the failed coup, the police had not taken conspiracy rumors against Tam seriously enough to arrest him, but as soon as he learned of the impending trial he committed suicide by ingesting cyanide . He left a farewell letter in which he wrote: "I also take life as a warning to those who trample on all freedoms", reminding of the monk Thích Quảng Đức , who recently protested against the Buddhist persecution of Diệm himself had burned. Tam's suicide caused mixed reactions. While some observers saw it as an affirmation of the Vietnamese tradition of choosing death over humiliation, some VNQDD members dismissed Tam's act as romantic and sentimental.

The short trial began on July 8, 1963. The seven officers and two civilians who fled the country after the coup were sentenced to death in absentia . Five officers were acquitted and the others were sentenced to between five and ten years in prison. Another VNQDD leader, Vu Hong Khanh , received six years in prison. Former minister Diệms Phan Khắc Sửu was sentenced to eight years, mainly for having signed the Caravelle Group's appeal for reform. Rebel spokesman Dan received seven years in prison. 14 of the civilians were also acquitted, including Tam.

Those sentenced to prison terms were released after the successful coup against Diệm in November 1963, in which he was murdered. On November 8, the military junta released Diệm's political opponents who had been imprisoned on the island of Poulo Condore . Dan was led to military headquarters hung with garlands. On November 10, Suu was released and greeted by a large crowd at the town hall. Suu later served briefly as president and Dan was intermittent vice prime minister. Thi returned to Vietnam and resumed his service with the ARVN.

literature

- Anne E. Blair: Lodge in Vietnam: A Patriot Abroad . Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut 1995, ISBN 0300062265 .

- Arthur J. Dommen : The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans: Nationalism and Communism in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam . Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana 2001, ISBN 0253338549 .

- David Halberstam , Singal, Daniel J .: The Making of a Quagmire: America and Vietnam during the Kennedy Era . Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, Maryland 2008, ISBN 0-7425-6007-4 .

- Ellen J. Hammer : A Death in November . EP Dutton, New York City, New York 1987, ISBN 0-525-24210-4 .

- Seth Jacobs: Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diệm and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963 . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, Maryland 2006, ISBN 0-7425-4447-8 .

- Stanley Karnow : Vietnam: A history . Penguin Books, New York City, New York 1997, ISBN 0-670-84218-4 .

- AJ Langguth: Our Vietnam . Simon and Schuster, New York City, New York 2000, ISBN 0-684-81202-9 .

- Mark Moyar : Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965 . Cambridge University Press, New York City, New York 2006, ISBN 0521869110 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Marc Frey : History of the Vietnam War . Beck, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-406-45978-1 , p. 60

- ^ Seth Jacobs: Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diệm and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers 2006, ISBN 0-7425-4447-8

- ↑ a b c d e f Arthur J. Dommen: The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans: Nationalism and Communism in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press 2001, ISBN 0253338549 , p. 418.

- ↑ Ellen J. Hammer: A Death in November. New York City, New York: EP Dutton 1987, ISBN 0-525-24210-4 , p. 131

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Mark Moyar: Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965. New York City, New York: Cambridge University Press 2006, ISBN 0521869110 , p. 109.

- ↑ Ellen J. Hammer: A Death in November. New York City, New York: EP Dutton 1987, ISBN 0-525-24210-4 , pp. 131-133.

- ^ A b c d e Seth Jacobs: Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diệm and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers 2006, ISBN 0-7425-4447-8 , p. 117.

- ^ David Halberstam: The Making of a Quagmire: America and Vietnam during the Kennedy Era. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield 2008, ISBN 0-7425-6007-4 , p. 23.

- ↑ a b c d Ellen J. Hammer: A Death in November. New York City, New York: EP Dutton 1987, ISBN 0-525-24210-4 , p. 131

- ^ Stanley Karnow: Vietnam: A history. New York City, New York: Penguin Books 1997, ISBN 0-670-84218-4 , pp. 252 f.

- ↑ a b Mark Moyar: Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965. New York City, New York: Cambridge University Press 2006, ISBN 0521869110 , p. 108.

- ↑ a b c d e f Mark Moyar: Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965. New York City, New York: Cambridge University Press 2006, ISBN 0521869110 , p. 110.

- ^ A b c Stanley Karnow: Vietnam: A history. New York City, New York: Penguin Books 1997, ISBN 0-670-84218-4 , pp. 252 f.

- ↑ a b c Ellen J. Hammer: A Death in November. New York City, New York: EP Dutton 1987, ISBN 0-525-24210-4 , p. 132.

- ↑ Mark Moyar: Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, from 1954 to 1965. New York City, New York: Cambridge University Press 2006, ISBN 0521869110 , pp. 109 f.

- ↑ a b c d e f Seth Jacobs: Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diệm and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers 2006, ISBN 0-7425-4447-8 , p. 118.

- ↑ a b c A. J. Langguth: Our Vietnam. New York City, New York: Simon and Schuster 2000, ISBN 0-684-81202-9 , p. 108 f.

- ^ A b c d e Mark Moyar: Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965. New York City, New York: Cambridge University Press 2006, ISBN 0521869110 , p. 111.

- ↑ a b c d e Arthur J. Dommen: The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans: Nationalism and Communism in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press 2001, ISBN 0253338549 , p. 419.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Mark Moyar: Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965. New York City, New York: Cambridge University Press 2006, ISBN 0521869110 , p. 114.

- ^ A b c d Mark Moyar: Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965. New York City, New York: Cambridge University Press 2006, ISBN 0521869110 , p. 112.

- ↑ a b c Mark Moyar: Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965. New York City, New York: Cambridge University Press 2006, ISBN 0521869110 , p. 113.

- ↑ a b c d Seth Jacobs: Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diệm and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950–1963. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers 2006, ISBN 0-7425-4447-8 , p. 119.

- ↑ a b c Ellen J. Hammer: A Death in November. New York City, New York: EP Dutton 1987, ISBN 0-525-24210-4 , p. 133.

- ^ A b c d e Mark Moyar: Triumph Forsaken: The Vietnam War, 1954-1965. New York City, New York: Cambridge University Press 2006, ISBN 0521869110 , p. 115.

- ^ David Halberstam: The Making of a Quagmire: America and Vietnam during the Kennedy Era. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield 2008, ISBN 0-7425-6007-4 , p. 180.

- ↑ Ellen J. Hammer: A Death in November. New York City, New York: EP Dutton 1987, ISBN 0-525-24210-4 , pp. 127 f.

- ↑ Ellen J. Hammer: A Death in November. New York City, New York: EP Dutton 1987, ISBN 0-525-24210-4 , p. 126.

- ↑ a b c d e Ellen J. Hammer: A Death in November. New York City, New York: EP Dutton 1987, ISBN 0-525-24210-4 , pp. 154 f.

- ^ Anne E. Blair: Lodge in Vietnam: A Patriot Abroad. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press 1995, ISBN 0300062265 , p. 70.

- ^ Anne E. Blair: Lodge in Vietnam: A Patriot Abroad. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press 1995, ISBN 0300062265 , p. 81.

- ^ Stanley Karnow: Vietnam: A history. New York City, New York: Penguin Books 1997, ISBN 0-670-84218-4 , pp. 460-464.