Name taboo

The naming taboo is a cultural phenomenon in China and some neighboring countries in Asia. The main component of this taboo is not to name persons of respect by their personal names , either in writing or orally. Such name taboos existed long before the establishment of the Chinese Empire . The practice continued until its end, after which the relevant laws were abolished. The custom has since declined sharply.

Names and variants

The Chinese term bihui ( Chinese 避諱 , pinyin bì huì ) has changed in its literal meaning. The first character can be used, among other things, as avoidance, polite rejection . The second character stood in the early 1st millennium BC for making mistakes . Since the time of the Warring States, however, the later meanings of fear / hesitation and concealment / masking have been codified with a clear and later exclusive reference to the name taboo, for which it stands in modern Mandarin . Other terms are 忌諱 , jì huì and 禁忌 , jìn jì for taboos in general.

The bihui (name taboo) is part of a broader cultural taboo that roughly feels offensive to the following five things (especially mentioning them in a cultivated conversation): body excretions, sexual organs and acts, illness and death, personal names, saints and deities. While most of these taboo topics are understandable from a European-Western perspective, this does not apply to the names.

The taboo of the (personal) name of the ruling prince and all of his ancestors ( 公 諱 , gōng huì - "prince's taboo; public taboo", alternatively also 國 諱 , guò huì - "state taboo, national taboo") became particularly well known in western culture. . At some times this taboo also included other members of the imperial family, such as the empress. All subjects of the state had to adhere to this taboo.

However, numerous other persons of respect were subject to individual name taboos, which were different for everyone: The personal name of one's own father and other ancestors was to be avoided. This also applied to persons of respect in the larger family association (clan). How many previous generations of ancestors had to be taken into account was subject to social convention, the number seven is often mentioned here. This was referred to as 家 諱 , jiā huì - "family taboo ". Students were also not allowed to pronounce or write their teacher's name; close friends, their own superiors and government officials were also honored through the bihui .

Until the early 20th century, several sinologists saw a difference between the Western term taboo (a loan word from Polynesian, which therefore had the connotation of spiritual-religious superstition) and the Chinese bihui , which, in addition to its religious and moral components, also shamed the unclean taboo breaker and should not be equated with the Polynesian tapu customs. Other researchers contradict this and point out that the bihui also has a recognizable history of development.

Besides China, there were also naming taboos in Korea and Japan .

Methods of bypassing

The methods of adhering to the naming convention included:

- Omission of the taboo sign, at times also covering with special yellow paper.

- Incorrect spelling of the taboo character, usually by omitting the last dash from the end of the Song dynasty.

- Replacement of the taboo character or syllable by another with the same sound ( homonym ) or a similar appearance. This often required great linguistic understanding, because in some times either homonyms or similar signs were taboo. In the case of frequently occurring words with taboo signs, the desired language forms have been officially regulated.

- Avoiding the taboo name by using a synonym or another choice of words.

Stories in which particularly zealous people also consistently avoided the physical object itself, which they were personally taboo to mention, probably belong in the area of legends. In the course of time, rules emerged as to which people (groups) had to observe which taboos in which social context, and these rules were also part of the bihui concept. As early as the Han dynasty , there were also sets of rules and documents in which taboos were set out and discussed. In some cases, official lists of taboo rulers' names were even made so that the taboo could be correctly observed in official correspondence without harming those involved. At a lower level, too, when dealing with new acquaintances, for example, it was also important to make the name taboos so clear to the other, as yet unknown, that it was then clear to all those involved which syllables and symbols could be used.

Methods of toning down taboos

Numerous rulers were aware that their name could pose great problems to the population. Against this background, practices are to be understood in which a posthumous name is given after death (also commonly used in historiography) and an official ruler name is used instead of the personal name as the salutation. The personal name was also changed to make taboos more acceptable. The maiden name or previous personal name was then no longer taboo, only the current one. Later dynasties sometimes completely avoided giving their princes names with common characters or syllables, but deliberately chose highly literary and rare names. There are several examples of milder application of the taboo:

- Han Xuandi (91–49 BC) changed his personal name 病 已 , bìng yǐ with two very common characters to the less common word 詢 , xún .

- Han Mingdi (28–75) changed his personal name 陽 , yáng - " sun " to 莊 , zhuāng .

- Wei Yuandi changed his personal name from 曹 璜 , caó huáng (huáng is 'yellow') to 曹 奐 , Cao Huan .

- Tang Taizong (599–649) ordered that his personal name 世 民 , shì mín with two very common characters should only fall under the bihui if both characters were directly behind one another. His son Tang Gaozong revoked this order in memory of his father during his own reign, which is why even his chancellor had to change his name.

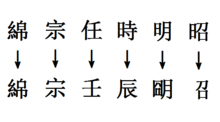

- The Daoguang Emperor (1782–1850) changed his name from 綿寧 , mián níng to 旻寧 , mín níng .

rating

The name taboo was perceived by Chinese philosophers as an indispensable part of their culture: the name can be understood as the essence or soul of being, the ingenious circumvention of the name as the cultural heart of civil society. Failure to observe taboos was thus barbarism and a sign of the decline of moral mores.

The name taboo was also a formative element in the development of the Chinese language. Over the centuries, thousands of personal names, titles, geographical names and vocabulary have been changed in order to comply with national name taboos. Among them were about a month names: The month 政月 , zhèng yuè - "(literally administrative month )" was in 正月 , zhèng yuè - "(literally upright month )" changed, and later in 端月 , Duan yuè - "(literally ordinary Month ) ". Many dynasties lasted long enough for the older names to be forgotten. Even older works were no longer allowed to be reproduced unchanged if newer name taboos had to be observed. In some cases, even older chronicles have been edited so as not to embarrass the reader into reading a taboo name.

Qian Daxin (1728–1804) was the first Chinese historian to take advantage of the name taboo to date texts from past periods based on the taboos followed therein and, if necessary, even to determine the authorship if this was questionable. To this day, this method is a particularly important element of Chinese historical textual criticism . On the one hand, she uses the taboo names of rulers themselves as well as the method with which the taboo was followed.

Despite numerous learned works on the bihui , it was not until 1928 that Chen Yuan wrote a systematic and comprehensive scientific work on the methodology and effects of taboos. Further thorough processing of the topic began in the 1990s. The phenomenon of taboos was reported in the West as early as the end of the 19th century, as was the extent to which the Chinese were often offended by the uncivilized disregard of their customs by the Europeans.

A phenomenon that is partly explained as different, namely a general naming taboo with regard to religious, supernatural and magical phenomena (comparable to the western taboo regarding the devil's name ), is also assigned to the name taboo as a secondary topic in today's People's Republic of China. Conversely, however, the emergence of the name taboo can also be interpreted from a partial aspect of the general linguistic taboos.

Development history and examples

In the Tang Dynasty , the name taboo was massively expanded. While the first Tang emperors tried to mitigate them and also changed their names, later emperors no longer thought of the effects of the name taboo on their subjects. The ruler's temple name , grave name and government motto fell under the taboo. Many name taboos were set up in particular by usurpers, who were particularly concerned about the legitimacy of their rule. For example, Wu Zetian made the personal names of her parents, children and sons-in-law taboo throughout the country. Even before her reign, province and city names were changed in order to comply with the princely name taboo; even the names of monuments and temples have been changed.

Personal name taboos shaped life and could also prevent careers: The Tang legislation forbade anyone, under threat of one year of detention, to accept an office or title if the name to be used violated a paternal or grandfatherial taboo of the incumbent. This was true of civil administration and military posts. Many Chinese were therefore unsuitable for certain positions because of their family history; From the Tang Dynasty there are mainly cases in which a character of the desired title was taboo. The poet Li He (approx. 790–816) became famous: he was denied higher civil service because the necessary exam would have given him a title that would have contained a character that was a homophone to his father's first name. This subtlety will have been an intrigue, but it shows the weight that society has given to taboo. A contemporary of Li's, Han Yu , commented on the case as follows: If the father's name was 仁 , rén - “humanity”, could the son be allowed to be a 人 , rén - “man”? However, the censorship of homonyms could still be successfully petitioned at court, as an example from the Tang dynasty shows, where the Chancellor Li Xi used a homonym for a taboo name in a document, was punished, but was pardoned after his objection .

The short-lived successor empires of the Tang Dynasty also paid close attention to name taboos - for example the Later Liang Dynasty , which replaced the Tang taboos with their own; or the Later Tang Dynasty , which painstakingly tried to tie in with the alleged predecessor Tang dynasty with its taboos. Edicts with instructions for naming taboos have also been preserved for the later Jin , Han and Zhou dynasties. The same practices can be assumed for the southern kingdoms of the same period , even if less written evidence has come down to us. There, for example, all names that contained a homonym of Liú were changed because the ruler of Wuyue 錢 镠 , Qian Liú was called. In addition to numerous family names, the pomegranate ( 石榴 , shíliú ) was also affected, it was renamed 金 櫻 , jīnyīng - " golden cherry ". It has been observed that in southern China, phonetic equivalents are more strictly taboo than written similarities.

The naming taboo reached a new high point in the Song dynasty (960–1279). Just two weeks after the enthronement, the younger brothers of Taizu, the founder of the dynasty, had to change their names because they had the same initial character. The youngest brother changed his name for the second time when the middle brother Taizong also came to power (see Emperor of the Song Dynasty ). The Song dynasty attached great importance to ancestor worship, so that the great-great-grandfather of the dynasty's founder was taboo, not to mention the personal name of the Yellow Emperor , to which the Song can be traced back. The southern songs made homonyms taboo, which increased the number of forbidden characters enormously. Hundreds of taboo signs that were valid at the same time have been handed down for the song era. To compensate for this, the custom was introduced to be able to write out the taboo characters without the final stroke, see. o. After the Song dynasty, the number of taboo characters decreased again.

Compared to the Song Dynasty, the Yuan and Ming Dynasties were quite tolerant of their naming taboos, which nevertheless had to be observed. In the Qing Dynasty , particular attention was paid to compliance, the so-called Literary Inquisition took place in the latter . The Qing dynasty (presumably) had far more death sentences for name taboos than previous dynasties. The following prominent examples have survived, but it should also be emphasized in these cases that the taboo breakers were the highest public servants.

- Zha Siting (1664-1727) was a high official who found the sentence of a classical poem correct in a civil service examination , in which two characters resembled the name of the reigning Yongzheng emperor, only the top lines were missing. He was imprisoned for symbolic beheading of the emperor and died in prison; his body was then publicly divided. His family members also fell under clan liability , and state examinations were no longer held in that province for some time.

- Wang Xihou (1713–1777) was a scholar who wrote out the names of several rulers as well as that of Confucius in the introduction to a work , instead of omitting the last line. This is said to have been an oversight, which he was unable to correct in the early prints of the book from 1775. The Qianlong emperor, himself affected by the desecration of his name, had him executed for high treason and exterminated his family. The scholar's private fortune was also confiscated and his books destroyed.

The state taboo on names and the corresponding legislation were officially abolished in 1911. Privately practiced name taboos and sometimes also the polite public avoidance of respected names survive to this day, both in the People's Republic and in Taiwan.

The role of women in the name taboo

The naming taboo was practiced by women in the same way as by men. A woman's name taboos , however, were considered a home taboo ( Chinese 内 諱 , pinyin nèi huì - " indoor taboo") in accordance with her position in patriarchal society and were therefore only to be observed in her household - but there with the same consistency and severity as the external taboo of men. It is known, for example, that before a performance in the private circle of the empress, artists first had to inquire about the home taboos in her palace and then obey them. The children of a household also had to follow the same taboos within their home as the mother. (See also Women in Ancient China on this understanding of their roles.)

Outside the household or away from the family, however, according to the Book of Rites , family members were allowed to pronounce the female taboo names, and only those of the father had unlimited validity. The (external) taboo names of all ancestors were also not transferred to the new family when a daughter married, since, according to the idea of patrilinearity, they belonged to a different family than that of the bridegroom. Correspondingly, women were not entered in genealogical records with their entire family tree, but at most with a reference to which family / clan they came from. In the event that their own name violated a taboo in the man's family, women also had to change their personal names.

However, only cases in which the home taboos were disclosed to the public have been reported. Because of this non-tradition, far less is known about the application of naming taboos to women than about that of men.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Adamek 2017, pp. 6–8

- ↑ He Yun, 2016. p. 380.

- ↑ Adamek 2017, p. 3

- ↑ Adamek 2017, p. 9

- ↑ Adamek 2017, p. 1, p. 219. He cites “stone” and “music” as examples.

- ↑ Adamek 2017, p. 219

- ↑ Adamek 2017, p. 4

- ↑ Adamek 2017, p. 11

- ↑ Adamek 2017, p. 13

- ↑ Adamek 2017, p. 219 f.

- ↑ Adamek 2017, p. 150.

- ↑ Adamek 2017, p. 157 f.

- ↑ Adamek 2017, pp. 159–164

- ↑ Adamek 2017, p. 210

- ↑ Adamek 2017, pp. 1f.

- ↑ Adamek 2017, pp. 203–210, p. 256

- ↑ Adamek 2017, pp. 249-256

literature

- Piotr Adamek: A good son is sad if he hears the name of his father: The Tabooing of Names in China as a way of implementing social values . Routledge, 2017, ISBN 9781351565219 . Digitized . Dissertation, Universiteit Leiden, 2012, hdl : 1887/19770 .

- Amy He Yun: Taboo, naming and addressing. In: The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Chinese Language . Routledge, 2016, ISBN 978-13-173-8249-2 , pp. 387-392.