Women in ancient China

From the early days of China to the end of the Chinese Empire in 1911, women in traditional Chinese society were largely excluded from social participation.

Chinese history certainly knew outstanding and even powerful women, but according to the traditional gender role of women, she should stay within her home and only work there, be as uneducated as possible and be subordinate to male family members. The teachings of the Confucianist state , which hardened over time, are perceived as the most important factor in the oppression of women. In a development that spanned many centuries, women were gradually further degraded: They were not allowed to own property, had to mutilate their feet and were not viewed as independent people, but even as commodities. Although there were exceptions within the cultures of China, as well as attempts at reform by the state, substantial improvements in the situation of women only came with the Chinese revolution .

Basics

The Sinology deals today especially with deliberately traditional, often official correspondence sources that of contemporary (self-) censorship, conscious selection of literary material and even historical revisionism subject. Accordingly, didactically oriented deliberate traditions written by men on the subject of women tended to moralize in a traditional way and to directly evaluate good and bad types of women. For a differentiated view, works of art, buildings, grave facilities, devices and items of clothing should also be used. Even educated women were active in literature, but these testimonies have survived in very small numbers and have not yet been adequately researched.

In the period from about the 10th century BC. Chr. To about the middle of the 20th century addition, there was a traditional image of women that relatively homogeneous evident in the face of a long observation period in his tradition in China. In the 20th century, the role of women in modern China changed rapidly and even several times in the wake of “women's liberation”.

If Chinese literature was divided into four types of text by the end of the Empire (legal, educational, poetic and explicit writings) and these types of text were evaluated separately, there was a tendency that women were increasingly portrayed as a threat to the male domain, which was "counteracted" with the help of successive restrictions of their rights. This development may not always have been equally pronounced and probably did not take place consciously. Research on this topic warns against generalizing the situation of women, as the available sources are not always reliable and only rarely allow a picture of society as a whole. Accordingly, evidence of the image of women depends on the time period, ethnic group, religious affiliation and social class, with the literary sources representing the perspective of the educated upper class.

Natural philosophical to religious basics for the subordination of women

A popular belief of the first millennium BC BC was probably codified in the I Ching ( Book of Changes ), in which the concept of Yin and Yang divides the areas of action of women and men as follows: The dark feminine ( yin ) should remain hidden in the interior / shadow of the house; the bright masculine ( yang ) moves in the light outside the house and thus in public ( nü zhi nei nan zhi wai ). Further aspects of this symbolism give women the role of the indulgent, receptive, calm and passive partner. A valuation in the sense of subordination of women is later than this basic idea of Taoism .

Legalism and Mohism were precursors to Confucianism . Already these philosophical schools propagated a gender segregation for the order of society: "Men plow, women weave" ( 男 耕 女 織 , nán gēng nǚ zhī ). This principle remained characteristic of almost all epochs in Chinese history. The central element of a woman's housework was textile processing:

“The women get up when day comes and sleep only at night. They spin and weave and organize the hemp, silk and bast threads, which they process into fabrics and silk fabrics. These are their duties. "

By Confucius were five basic human relationships ( 五論 , wǔlùn ) defines, of which extend four relationships of the person in authority to subordinates, but only one from friend to friend. The third of the relationships was that of the man to his subordinate woman. Often absolute power was available to the person in authority. With these rules a hierarchically organized feudal society was postulated, in which the family and not the individual formed the smallest unit. This feudal society was continued within the women's world: the landlady or main wife commanded her hierarchically organized relatives and servants down to the level of slaves.

The Book of Rites imposed further restrictions: women should not participate in public affairs and their word should not come over the doorstep. Simplicity and lack of education are the ideal and virtue of the housewife. Conversely, men had no fundamental obligations towards women, apart from the obligation to look after their parents in old age, including their mother.

Through Menzius rules of threefold obedience were established: Before marriage, a woman should commit herself to respect and obedience to her parents; after marriage towards the man; after the death of the man to the male offspring. The rules of threefold obedience were later supplemented by four virtues of the wife: ethical responsibility (or moderation), language (or silence), appearance (or good looks) and works / behavior (including loyalty). Whether Menzius demanded a slavish obedience to his rules or merely the authority to make decisions in important decisions remained a matter of debate.

These Confucian rules severely restricted women; They were also denied access to patriarchal ancestor worship. Traditionally they tended towards Taoist folk religious, Buddhist or occult customs, which also included mother cults. After Buddhism established itself in China from the 6th century AD , the Guanyin received special veneration. However, Confucianism also assigned a special role to the mother: While the fathers of Confucius and Menzius are unknown today, their mothers are said to have stood up for them in exemplary fashion. In addition, mothers of the upper class in China often had considerable influence on their children: Despite the rules of the Menzius, the mother of an underage ruler regularly took over the reign or at least exerted a great deal of influence on his politics.

Effects on the social fabric

The philosophical principles had a fundamental effect on further regulations for women and on their role in the family: a role outside the family was forbidden according to this tradition. The birth of sons was assigned to her as the most important role, so that the ancestor cult of the paternal line could continue to exist. The woman also had to observe female name taboos in her household .

Before the age of seven, both girls and boys were brought up by their mother and other women in the household; Early education only separated from the age of seven: boys were then assigned to a male relative of their father. A girl in “good circles”, on the other hand, was kept in isolation from the age of seven under the supervision of an all-female group of servants; from the age of ten she had to learn female work (textile work and household supervision) and was married between the ages of 14 and 18.

The man had seven reasons to reject his wife ( 七出 , qī chū ): not giving birth to a son, loose lifestyle, lack of eagerness to serve in-laws , talkativeness , theft, jealousy and incurable illness. However, repudiation was again ruled out in the following circumstances: the wife had observed the mourning period for the in-laws; the man was wealthy enough to endure the wife anyway; the wife had no relatives to return to. Women were not entitled to divorce rights.

Classical literature

“How sad it is to be born a woman,

nothing on earth is so neglected!

Born boys appear like gods in earthly form.

Their hearts defy the four seas, the storm and the dust of ten thousand miles.

But nobody is happy about the birth of a girl,

the family does not value it.

If it gets bigger, it hides in the room,

too scared to look a man in its face.

Nobody cries when it finally disappears from the house - suddenly like a cloud after the rain.

[...] "

Scholarship (such as historiography or reference works) suppressed the topic of women as much as possible, but gave it a limited space: the section of women's biography, to portray exemplary women of their time, usually characterized by an emphasized quality that is praised. Many such biographies are integrated into the historiography of the dynasties. What is striking here is that socio-ethical virtues ("chastity, filial piety, self-sacrifice, sense of duty") gradually came to the fore from the middle of the imperial period and reached a peak of dominance in the Ming period, while individual characteristics ("beauty, quick wittedness, artistic [ …] Talent, cleverness, happiness in life ”) were postponed. It was not until the Qing period that a balance similar to that of the early imperial period was restored. Edited works were also selected accordingly: Zhu Xi (1130–1200) made a restrictive selection in a new edition of a collection of women's biographies: If “brave mothers […] daughters, sisters, friends” were also honored beforehand, Zhu Xi merely selected biographies , to which the following three images of women apply: the self-sacrificing mother who brings up her son; the daughter-in-law who takes care of the absent man's parents; and the chaste widow who also dies soon after the husband's death.

Unlike most of the upscale court literature, the “folk literature” (such as sagas, songs, ballads, jokes) also includes noticeably strong to dominant female characters. Here, however, it is unclear whether it is about male projections, wishes or even fears, or whether the social position of women is portrayed there more authentically than in highly literary court literature.

Entertainers, prostitutes, work outside the home

Only service providers of different kinds (e.g. musicians, dancers, courtesans) should be trained and instructed in the aesthetic arts - these service providers were therefore considered to be useless for the domestic role of women. An example of this are the five Song sisters who held high positions at court in the 9th century as entertainers, but did not marry or were taken as concubines.

The earliest evidence of prostitution can be found since the Zhou period; unlike in Europe, it was openly tolerated, even if it contradicted the domestic role of women and Confucian morality. There were different forms, from daughters of the upper class down to peasant women. Concubines and concubines, who were only available to their husbands for sexual purposes, were always within the socially accepted norm, but mediation with other partners was viewed as morally questionable. For the year 720 BC It is already known that brothels were taxed and were also under state supervision. In the Chinese dynasties up to the fall of the Song dynasty in the 13th century, the institution of the courtesan system remained more or less untouched, in the following Yuan dynasty prostitution was officially prohibited. However, Marco Polo claims to have still counted 20,000 prostitutes in the suburbs of Beijing. All sexuality outside of marriage was completely discredited due to neoconfucianism during the Ming dynasty: sexual intercourse should only serve the purpose of procreation. During the Qing Dynasty, prostitution fell further into disrepute when the British colonial powers combined it with opium consumption . In 1861 there were reports of 25,000 girls in 3,650 entertainment venues from the port city of Amoy (300,000 inhabitants). During this time, so-called “flower ships” (moored houseboats) functioned as brothels and “blue houses”. These brothels were cultural sites that offered evening entertainment, food, music, games and tea parties. European travelers reported that they had "noticed nothing improper". However, the entertainers did not enjoy any cover and usually had to keep themselves afloat with odd jobs at the end of their careers.

Various other professions made it possible for urban women to perform other services outside the home, such as selling groceries or doing textile work on the street. The marriage brokerage was even entirely in the hands of the women, as only they were allowed access to the women's apartments in all houses. The activity as a Buddhist nun was respected, with women there being obliged to breastfeed and serving tasks. Taoist priestesses often came from the upper class. When Taoist and Buddhist institutions have been associated with sexual services, one can often suspect a Confucianist-motivated defamation against women in positions of power.

Ideals of beauty and behavior

The woman's ideal of beauty has changed over time, and a striking tendency can be seen when comparing artistic testimonies. Paintings from the early imperial era show "broad hips, luscious, bare breasts, round full-cheeked face" as the ideal of women; by the late imperial era, this ideal was transformed into a "slim, almost fragile and emaciated figure in a high-necked costume".

A particularly large number of naturalistic female statuettes have come down to us from the Tang dynasty. As the following series of images shows, fashions and ideals of beauty changed again and again within just a hundred years.

"If a woman is too educated, she only brings annoyance and inconvenience, but never an advantage."

According to traditional rules, women should only move around the house. The upbringing took place there as early as the youth, usually by the mother, which perpetuated the tradition and, as a rule, consolidated it in conservative circles. Female upbringing was aimed at giving up one's own personality and will: “The lack of education is a virtue in women,” which is why literary or musical education was frowned upon. The desired characteristics, however, included a specific female language and specific female forms of grace, virtue and work. The latter concerned the household activity to be expected, depending on the social status. The patriarchal order demanded female submission according to the teachings of Menzius: women were assigned to their family (i.e., the father, husband or son) - since they had no legal status of their own - and had to function within them. When this male caregiver changed, the relationship environment also changed immediately. A young daughter-in-law deserved the lowest rank in the family structure. The daughter-in-law only received status and family legitimation through the birth of a son. The resulting aggression and compulsions were, as soon as the opportunity arose, derived from lower social family members - such as one's own daughter-in-law, who was suppressed by all means in numerous traditional cases. According to the Confucian view of the world, jealousy towards other women was not intended if both women belonged to the same nuclear family. Nevertheless, not only in the courtly upper class have examples of intrigues within the family that male family members could not escape and which led to the erosion of the outwardly harmonious patriarchal facade. Confucianism also recognized the grandmother of a family as a special female authority.

The idea of fetal education dates back to the imperial era - the behavior of women during pregnancy should therefore have a particularly decisive influence on the development of the child in the womb. Accordingly, there were special medical, psychological and religious treatments.

historical development

Pre-imperial time

In the pre-Confucian era, women played active roles across society and gender roles were not pronounced. Burial rites of pre-dynastic Chinese cultures took different forms: For example, the Majiayao culture buried its relatives with gender-specific tools, but without social ranks, while the Qijia culture placed the man as the central element of the tomb and gave women a peripheral role. A form of matriarchy was even assumed to be the earliest Chinese social order . References to matrilineal filiation can be found in linguistics (the sign 姓 , xìng - “family name” emphasizes the role of women, the oldest clan names also contain the radical for women). The goddess Xiwangmu plays a major role in folk religion; the divine couple Fu Xi and Nuwa appear in the role of an equal partnership or primordial family; the earliest ancestral cults are said to have worshiped the mother. The retention of matriarchal elements has also been demonstrated in some of today's minorities in China .

Examples of influential women of the Shang dynasty are, for example, Fu Hao , one of three main wives of the Shang king Wu Ding with the rank of military leader; but also Daji , concubine of the Shang king Di Xin and allegedly partly responsible for the downfall of the Shang dynasty. In the subsequent Zhou dynasty, Queen Yi Jiang also held the post of Minister of Zhou Wuwang .

At the latest in the 10th century BC A patriarchal society had developed: children were now assigned to the father ( agnatic inheritance); Various schools of philosophy established the well-structured cosmic worldview that has been valid since then, which became a new tradition around the year 500 BC. Was also enshrined in law.

The common mothers of Confucius and Menzius made famous for following the restrictions on women. Zheng Mao was known as an exemplary lady-in-waiting . Other heroines of pre-dynastic China played their role in the background: The wife of Prince Mu von Xu, who is no longer known by name, was a born Princess von Wey and was a poet. She saved her native land in the 7th century BC. BC, because they were able to organize a relief army in time. Also in the 7th century, concubine Qi Jiang motivated her exiled husband Chong'er to recapture his throne as Wen of Jin , which earned him the position of hegemon of China. Fan Ji was the moral authority for her husband, Chu Zhuangwang , who moved him from a passive to an active style of government. The concubine and later queen widow Xuan of Qin (born in the 3rd century in Chu ) acted as regent for her son. The ruler of Wei's co- consort Ru Ji became known for her role as a heroic agent in the service of Zhao State. The beauty Xi Shi is said to have been partly responsible for the fall of the state of Wu .

Early Imperial Period to the end of the Tang Dynasty

In the Qin Dynasty , the first and only brief dynasty to unite the Chinese Empire, the Confucianist ideology was further strengthened and anchored in the centrally governed state. Changes to the situation of women were therefore only made where Confucianism was not previously firmly anchored. In retrospect, the period of the subsequent Han dynasty is viewed as less dogmatic: women were able to remarry after their husband died. Even the commandment that women always marry into the man's house was not strictly followed in the case of impoverished husbands, although this resulted in the man's social decline. Women with farmed property of their own could even be taxed.

Ban Zhao (approx. 45–116) is considered to be a pioneering personality in the restriction of women , who herself enjoyed great freedoms, and although she admitted some desirable freedoms in her widely read book ( Commandments for Women ), she also recommended considerable self-restraint to her daughters. Due to the widespread use of her family guide, she severely restricted the design options for later generations. At the latest by them the rules of Menzius were supplemented by the fourfold virtues, which they precisely described: according to the traditions one had to be measured and not attract attention; the woman should speak little and only when asked; she should make herself attractive to the man; she should willingly do all the housework and faithfully carry out the husband's sons.

Well-respected women of the Han period were once again primarily privileged ladies-in-waiting and various empresses. General Xiang Yu's concubine , Yu Miaoyi , accompanied her husband on his campaigns and committed suicide after his death. The wife of the first Han emperor, Lü Zhi , ruled as the widow of the empress from 195 to 180 BC. Over the empire, which was nominally ruled first by her son, then two grandchildren. The influence of Empress Dou (empress widow from 157 to 135 BC) on politics was less direct; it is nevertheless associated with a heyday of Han China. The elevation of Confucianism to the state ideology and the downgrading of Taoism could not prevent it. Empress Wei Zifu , the second-longest-lived empress in the history of China, was considered particularly virtuous. Liu Xijun , Liu Jieyou, and Wang Zhaojun were imperial princesses who were married to the Wusun and Xiongnu rulers of west and north of China; in their wake and Feng Liao , the first ambassador of China. Other important empresses were Wang Zhengjun , Yin Lihua , Ma and finally Dou , who ruled from 88-92 as her son's regent. Empress Deng Sui ruled for her son from 106 until her death in 121, but his widow Yan Ji was unable to take power in 125. Chunyu Tiying was considered a heroine after she persuaded Emperor Han Wendi to mitigate the Five Sentences . The poets Zhuo Wenjun (2nd century BC), Ban Jieyu (turn of the millennium) and Cai Wenji (2nd century) are also known.

After the Han Dynasty, during the Three Kingdoms , Fu Xuan wrote a much-noticed poem on the situation of women, already cited as an excerpt above. Ms. Zhan , who became known for her role as an exemplary mother and educator of the virtuous Tao Kan , and Sun Shangxiang , who became the model for a heroic fictional character , also lived at the same time . Zuo Fen (3rd century) and Su Hui (4th century) were other poets. In the time of the Southern and Northern Dynasties there was greater cultural exchange with the "barbarians" across the borders. The rules of Confucianism were still formally valid, but were less strictly observed. The following period until the 9th century is considered the heyday of Taoism and Buddhism, which was newly established in China. This allowed women to be particularly influential as political advisers and regents to their husbands and sons. Dowager Empress Feng ruled for her son Xiaowen of the Northern Wei Dynasty from 476 to 490. Xian caused a sensation in the 6th century as a noble warrior and commander of a non- Han people . In the 5th or 6th century, the legend of the Hua Mulan , who goes to war disguised as a soldier, was born.

Sui Wendi reunified China in 581 under his Sui dynasty , in which his wife and closest political advisor Dugu Qieluo played a decisive role. His successor Sui Yangdi abolished the right of women to own property, which also meant that women were no longer taxed as individuals. Subsequent dynasties also retained this principle. Heads of the Tang family had to pay a fixed amount of home-made textile products for every woman.

The Sui were overthrown by the Tang Dynasty in 618 after less than four decades . The daughter of the first Tang emperor, Pingyang , was a rebel leader and commanded an army of 70,000 men. It is believed that women continued to enjoy quite a lot of freedom during the Tang Dynasty: married women also achieved fame as artists and writers; In the performing arts as well as in literature there are happy and sensual women.

At the same time, however, the trade in women also increased. The legal status of certain groups of women solidified: a man should only have one wife ( 妻 , qī ). All concubines ( 妾 , qiè ) and their female descendants were placed in a lower position and had to serve the wife like maids. The maid or maid ( 婢 , bì ) was usually unfree and even lower in rank than a concubine. The concubine, once a privilege of the nobility, became the social norm in affluent and ultimately petty-bourgeois families. She was totally dependent on her lover / client; their sons were to be adopted by the wife; the daughters had to hire themselves out. That these conditions were detrimental to family peace is shown by the emergence of numerous stories on the subject of quarrelsome and jealous women who slander, intrigue and even murder. The moral models who followed the traditions and moral rules established in the classical educational literature were highly praised.

In the case of diplomatically arranged marriages with the neighboring peoples, unlike in previous dynasties, actual members of the ruling family were placed instead of adoptive princesses and married women. The Tang princesses acted as ambassadors at foreign courts, such as Wen Cheng in Tibet and Princess Taihe in the Uighur Khanate. Foreign cultural influences also found their way to China in the cosmopolitan Tang dynasty: In the 7th century, the nomadic people of the Tuyuhun adopted full veils - but this was only a temporary fad that was replaced by a veil in the 8th century falling off the headgear. This veil, too, later went out of fashion.

In China itself, Empress Wu Zetian interfered in government affairs from 664, was regent for her sons from 683 and ruled herself as the only empress in Chinese history with the title of Huangdi from 705 . Other powerful women in this environment were the poet Shangguan Wan'er , the Dowager Empress Wei (ruled briefly in 710) and Princess Taiping.

The reason for a later decline in the appreciation of female creativity and labor is assumed to be the increased urbanization in the Tang era . In the second half of the Tang Dynasty - with an enormously grown imperial harem - the palace eunuchs gained greater influence on politics, which in turn challenged intellectual reform efforts of the civil servants and scholars, neo-Confucianism , which from the early 11th century a renaissance of Confucian values.

End of the classical period to the end of Mongol rule

The Song Dynasty (from 960) is seen as a special turning point in women's freedom. With the rise of Neo-Confucianism, but also less clear social upheavals, there was also a phase of increased Confucianist indoctrination within the women's world. Women tried to identify with the idealized images of women and willingly accepted New Confucian teaching. One of the new rules of conduct was that raped (thus unchaste) women committed suicide. Widows should not remarry now. Confucian hagiography praised the widow Gao Xing as a model, who cut off her nose so as not to attract admirers.

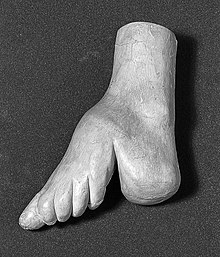

From the end of the Tang period, from the 10th century onwards, the tradition of foot tying (also: lotus foot, foot mutilation) dates back to which women were enormously restricted: girls with tied feet were able to follow the new Confucian ideology (exclusively to stay in the house and to provide their own role as a pleasure object) much easier to follow, as they could only walk longer distances with pain. At the same time, the family who married their daughter could demonstrate that the husband could expect obedience and the ability to suffer. This practice, whose origins lay in female dance, ironically led, through its excess, to a dramatic decline in female dancers and gymnasts.

One of the most important poets of the Song era was Li Qingzhao , whose literary work was subject to major changes in the course of her broken biography: Growing up in a comparatively liberal and life-affirming time, she wrote correspondingly cheerful, self-confident literature. Later she experienced numerous losses, so that gloomy and especially self-critical statements dominate her later work, so that Linck wants to deny her the quality of a "feminist" - she only wrote according to her environment, not against them. However, she wrote the only surviving female autobiography, in the form of an afterword to the work of her late husband.

The Yuan Dynasty (from 1279) brought no change in customs because the Mongol rulers adapted to what they believed to be a higher culture of the Chinese. The nomadic Mongolian way of life brought about a division of labor between the sexes, which was abandoned in the sedentary civilization. At the same time, the native Chinese also insisted on their tradition so that potentially foreign ideas did not penetrate Chinese culture. In the course of assimilation, for example, the tying of the feet also became popular among the Mongolian upper class.

Late Imperial Period (Ming and Qing Dynasties)

From the Ming and Qing periods, there has been a further increase in reports of suicide among newlyweds (presumably due to the family situation). The suicide of widows (comparable to widow burning ) was stylized as an exemplary expression of loyalty and chastity, which goes well beyond the already strict chastity laws of the Song era.

During the Ming Dynasty in southern China, the women's script emerged, with which women could communicate without having to resort to the official script monopolized by scholars.

During this time, the fox ghost stories, already known from earlier times , increased, in which the (negative) ghost beings transform into women and, after the seduction of men, suck out their life force. The tabooing of sexuality and the demonization of independent women are cited as a modern interpretation of this myth. However, it has also been suggested that such stories served to protect the rural female population because the spread of such stories resulted in fewer sexual assaults.

The poet Feng Menglong (1574–1646) repeatedly addressed women in his work, to whom he placed the traditional ideal of women; At the same time, there are types of women who show self-confidence, willingness to take risks and ingenuity. From the late imperial era, jokes have also come down to us that dealt with the fearful behavior of slipper heroes towards the female domestic tyrant.

The takeover of power by the Qing dynasty, which in China was perceived as foreign rule by the Manchu , had inflicted new layers of bondage on Chinese society: on the one hand, the Manchu suppressed the majority society of the Han Chinese, on the other hand, the Manchus were assimilated into Chinese society complete, that traditional moral concepts were interpreted more strictly than before. Non-Han Chinese also suffered cultural oppression from the Han. In addition, within the framework of the Unequal Treaties, there was the foreign influence of European powers, which after trade concessions also claimed colonies in China and thus imposed additional foreign rule. Faced with the threats posed by the Europeans, the Han Chinese have long been willing to support the culturally related Manchus rather than succumb to European influences. This lack of freedom and this lack of freedom of action weighed heavily on the people, and most heavily on women.

Nevertheless, the more intensive contact with the more progressive European image of women at the end of the 19th century also brought about a gradual change in perception - especially in missionary schools for girls and in education abroad, Chinese women came into contact with other values, which in some cases were vehement were also requested in their own environment. The first, but mostly endogenously motivated, reform movements by “radical intellectuals and officials” already existed in the final phase of the Qing dynasty, especially under the reign of the Dowager Empress Cixi , who ruled in place of her nephew from 1875 to 1908 (with an interruption of several years) .

The Qing Codex legal term of death for widows was three years; for the husband only one year. Deceased concubines were not mourned. The right of inheritance and property stipulated that daughters could not inherit; Sons, on the other hand, inherited (and in equal proportions, even if they came from a concubine). When a family fortune was divided, women could receive amounts, but there was no obligation to do so. Women were allowed to use family assets, but they were not allowed to dispose of their own funds. Divorce (rejection of the wife) was only allowed to the husband.

Aftermath: Modern Chinese Women

Traditional practices continued into the 20th century. In 1911 a major reform was initially postponed due to the proclamation of the Republic of China . There was committed activism by vocal feminists, but this was not supported by the institutions and was attacked by traditional forces. Only a few Chinese universities accepted female students from 1919 onwards. It was not until the mid-1920s that both the Kuomintang and communists realized the potential of women in unifying the nation. When the Chinese Civil War broke out in 1927 , these political forces took different paths, but each pursued a progressive women's policy. Due to the support of Hu Hanmin , the Republic of China fundamentally reformed family and marriage law in 1930, according to the principle of which women and men should be legally equated: From May 1931, for example, the female right to divorce applied; Mutual agreement on child care rights; Penalties for killing newborn women; Abolition of cohabitation. Nevertheless, full equality was not achieved; the implementing provisions of the Family Act preferred men and punished women much more severely for misconduct, especially in cases of domestic violence , very one-sided rules were laid down. More radical feminists (recognizable by their short haircut), who made demands beyond civil family law reform and were thus suspect of communism, were persecuted with the argument that equality had already been achieved. However, due to the civil war and / or the Japanese occupation , the family law could not be applied consistently anyway. The family law reform came to Taiwan (still a Japanese colony in 1930) in 1945, which established a rather conservative state based on the Confucian ideal. Further legislative changes to improve women's rights did not take place in the Republic of China until the 1980s.

In contrast, the social role of women in the People's Republic of China (from 1949, previously in the communist-ruled part of China) was fundamentally reinterpreted and revolutionary: the old ideal of women in the middle and upper classes as lady-in-waiting and housekeeper was viewed by Maoism as a bourgeois enemy; which is why the “liberation of women” was stylized as one of the party's greatest achievements. The woman was socially challenged as a worker and a fighter, even if the role of the socialist housewife and mother was also promoted. The Communist Party also paid great attention to ensuring that women's emancipation should take place within its ranks. Independent feminist organizations were undesirable.

It is estimated that the proportion of illiterate women in the final phase of the mainland Republic of China was around 98-99%, albeit in a society with an overall illiteracy rate of 80%.

Retrospective picture in the People's Republic of China

From the point of view of the Chinese communist women's liberation, in order to emphasize progress more clearly, an image of history reduced to all negative aspects was spread; summarized something like this: For over two thousand years, women were merely objects and possessions that could be used and traded accordingly. She was allowed to be beaten, forcibly married, raped or sacrificed to the gods even as a child; Children were allowed to be torn from her, and she was obliged to obey an almighty man all her life: first to her father, then to her husband, and after his death to her son. Female illiteracy corresponded to moral virtue. Because of the feudal economic order that had existed for thousands of years, there was no way for women in rural communities to resist this order, so that they ultimately had to remain powerless and desperate in the position assigned to them. For wealthy Han Chinese, the rules of cohabitation also applied: While they were forbidden from polygamy, privileged men were allowed to keep as many concubines as they could in addition to the main wife: These concubines were subject to everyone, including the main wife, and were not allowed to expect to be Old age to be cared for. Second children conceived by husbands had to expect the lives of servants or concubines; unless they were taken from their mother and adopted by the main wife. This two-class society was even more pronounced in rural areas (e.g. Tibet is emphasized), where the upper class was allowed both polygamy and concubinage, while in the lower class monogamy and sometimes, out of poverty, polyandry prevailed, i.e. several men shared one woman. The sudden upheaval of the situation with the arrival of communism is emphasized by this narrative: women who were previously objects, took their rights and justice into their own hands through the revolution as active persons. Unreasonable misogynists or polygams were severely punished by the collective on this occasion.

The Kai-Shek regime was also said to have continued the old situation - for example, it promoted forced prostitution.

swell

- Liu Xiang ( 劉向 77 BC – 6): Exemplary women's biographies ( 列 女 傳 , liènǚ zhuàn ; excerpt from the English translation in the Google book search).

- Ban Zhao (班昭, approx. 45–116): Commandments for women ( 女 誡 , nǚjiè ).

- Huangfu Gui (皇甫 規, 104–174): teacher or instructions for girls ( 女 師 , nǚshīzhēn ).

- Zhang Hua (張華, 232–300), illustration Gu Kaizhi (顧 愷 之, 344–405): teacher or instructions for girls ( 女 史 箴 , nǚshǐzhēn ).

- Song Ruoshen (宋 若 莘, 768–820): Analects for women. ( 女論語 , nǚlùnyǔ ; stylistically based on the analects of Confucius).

- Zheng (鄭, Tang Dynasty author): A girl's daughter-like awe. ( 女 孝经 , nǚxiàojīng ; Confucian social treatise ).

- Empress Zhangsun (長孫 皇后, 601–636, consort of Tang Taizong ): Female standard. ( 女 則 , nǚzé ; to educate girls at court).

- (unknown author of the Ming dynasty): Girls' Classic or The Daughter. ( 女兒 經 , nǚ'érjīng ; basic education for girls).

- Empress Xu / Renxiaowen (徐 皇后 / 仁孝 文 皇后, 1362–1407, wife of the Yongle Emperor): Instructions for the inner chambers. ( 內訓 , nèixùn ).

- Liu (劉, wife of Wang Jijing (王集敬), late Ming Dynasty): Short manual of all rules for girls or a balanced selection of female role models . ( 女 範 捷 錄 , nǚfànjiélù ).

- Lan Dingyuan (藍 鼎 元, 1680–1733): Women's Studies. ( 女 學 , nǚxué ).

- Zhu Hao (朱浩) and Wen Xingyuan (文 星 源), Qing Dynasty: Three Words for Women. ( 女 三字經 , nǚsānzìjīng ).

- Wang Xiang (1789–1852): The Four Books for Women. ( 女 四 書 , nǚsìshū ; consisting of Nǚjiè, Nǚlùnyǔ, Nèixùn and Nǚfànjiélù).

literature

- Bodo von Borries: Women in Ancient China. In: Annette Kuhn, Gerhard Schneider: Women in History. Volume 1. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1979, ISBN 3-590-18009-9 , pp. 223-274.

- Chen Dongyuan: History of Women in China. 1928 (reprint 1982).

- Elisabeth Croll: The Liberation of Women in China. Neuer Weg, Stuttgart 1977, ISBN 3-88021-073-X .

- Patricia Buckley Ebrey: The inner quarters: Marriage and the lives of Chinese women in the Sung period. University of California Press, Berkeley et al. a. 1993, ISBN 0-520-08156-0 (English).

- Michael Freudenberg: The women's movement in China at the end of the Qing dynasty. Brockmeyer, Bochum 1985, ISBN 3-88339-439-4 .

- Dagmar Hemm: Ways and wrong ways of women's liberation in China. Edition global, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-922667-33-3 .

- Lily Xiao Hong Lee, Agnieszka Dorota Stefanowska, Sue Wiles: Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women. 2 volumes. ME Sharpe, New York 2007/2015, ISBN 978-0-7656-1750-7 (English; Volume 1: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 BCE – 618 CE ISBN 978-1-317-51561-6 , reading sample ; Volume 2: Tang Through Ming 618–1644. Reading excerpt in the Google book search).

- Mechthild Leutner (Ed.): Women in China: The long march to emancipation (= argument study booklets. No. 70). Alfa, Göttingen 1987, ISBN 3-88619-770-0 .

- Gundula Linck: If the Duchess had written the songs instead of the Duke of Zhou, the tradition would be different. Problem and possibilities of historical women's studies using the example of China. In: Adam Jones: Non-European Women's History. Centaurus, Pfaffenweiler 1990, ISBN 3-89085-429-X , pp. 9-24.

- Julia Kristeva: The Chinese: The Role of Women in China. Nymphenburger, Munich 1976, ISBN 3-485-01838-4 .

- Tienchi Martin-Liao: Education for Women in Ancient China: An Analysis of Women's Books (= China Topics. Volume 22). Brockmeyer, Bochum 1984, ISBN 3-88339-400-9 (Note: translated the Nǚsìshū, but also analyzed it very critically; only available as a review of Leutner 1987 [SH70], pp. 25–28).

- Barbara Bennett Peterson among others: Notable Women of China. ME Sharpe, ISBN 0-7656-1929-6 (English; excerpt from Google book search).

- Elke Wandel: Women's life in the Middle Kingdom: Chinese women in the past and present. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1987, ISBN 3-499-18429-X .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Linck 1990, pp. 12/13.

- ↑ a b Until the 20th century, the Chinese language had no term for “emancipation / freedom (within society)”. The term ziyou used today for this originated from a positive reinterpretation of a previously negatively connoted word, which meant “licentiousness” (of the privileged who is free to disregard social and moral rules). See Hemm 1996, p. 5.

- ↑ Linck 1990, pp. 20 ff

- ↑ a b c Hemm 1996, p. 10.

- ↑ Kristeva 1976, p. 18. Kristeva explains, pp. 35–41, that Taoism postulates gender equality in sexual intercourse.

- ↑ Bodo von Börries: Women in ancient China . In: Women in History. Women's rights and social work of women in transition; specialist and didactic studies on the history of women. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1979, ISBN 3-590-18009-9 .

- ↑ Wandel 1987, p. 14.

- ↑ Wandel 1987, p. 17.

- ↑ Alexandra Wetzel: China. Empire of the middle. Volume 3 of the series: Image dictionary of peoples and cultures. Parthas, 2007, ISBN 978-3-936324-73-0 . P. 211.

- ^ A b Xinzhong Yao, The Encyclopedia of Confucianism. Keyword: Sāncong sìdé 三 从 四德 . Routledge 2015 (English; excerpt from Google book search).

- ↑ Wandel 1987, p. 22.

- ↑ Wandel 1987, pp. 17-20.

- ↑ Kristeva 1976, pp. 52/53.

- ↑ a b Hemm 1996, p. 12.

- ↑ Hemm 1996, p. 13.

- ↑ Original text in Chinese Wikisource: 苦 相 篇

- ↑ a b Linck 1990, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Linck 1990, pp. 11/12.

- ↑ Kristeva 1976, p. 56.

- ↑ Lily Lee 2007, keyword Song Ruoshen

- ^ A b c Paul Dufour (1806-1884, pseudonym FS Pierre Dufour): History of prostitution. 2nd volume. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-8218-0884-5 , pp. 193-196 (German by Bruno Schweigger).

- ↑ Alexandra Wetzel: China. Middle Kingdom (= image lexicon of peoples and cultures. Volume 3). ISBN 978-3-936324-73-0 , p. 214.

- ↑ Kristeva 1976, pp. 73–75, blames neoconfucian forces for the turnaround; Hemm 1996, p. 12 points to the Mongolian family morals

- ↑ Dufour; P. 195, cited ' Hildebrandt (II. P. 7)'

- ^ Based on Lewis 2009, p. 182; see. Kristeva 1976, pp. 73–75: It assumes temple prostitution.

- ↑ after Kristeva 1976, p. 57.

- ↑ Kristeva 1976, pp. 50–54, speaks here of women as a “nomadic being”.

- ↑ Leutner 1987, p. 25 ff.

- ↑ Kristeva 1976, pp. 50, 54, 58.

- ↑ Kristeva 1976, p. 60.

- ↑ Leutner 1987, p. 27.

- ↑ Lily Lee 2007, Preface p. VII

- ^ Yan Sun, Hongyu Yang: Gender Ideology and Mortuary Practice in Northwestern China. In: Katheryn M. Linduff, Yan Sun: Gender and Chinese Archeology. Rowman, Altamira 2004, pp. 45/46 (English; side view in the Google book search).

- ^ Wolfgang Franke: China manual. Düsseldorf 1974, pp. 370-371.

- ↑ Kristeva 1976, pp. 13-16.

- ↑ a b c d e Hemm 1996, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Kristeva 1976, pp. 21/22.

- ↑ Kristeva 1976, pp. 21, 46-48.

- ^ Bret Hinsch: Women, kinship, and property as seen in a Han dynasty will. In: T'oung Pao , Volume 84 Issue 1/1998.

- ↑ Linck 1990, p. 18 ff

- ↑ Hemm 1996, p. 11.

- ^ A b Mark Edward Lewis: China's Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty. Belknap Press, Cambridge 2009; Women in Tang Families. ISBN 978-0-674-03306-1 , pp. 180-189.

- ^ A b Charles D. Benn: China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press, 2004; Clothes and hygiene. Pp. 97-118; Life Cycle, ISBN 978-0-19-517665-0 , pp. 234–250 (English; side view in Google book search).

- ↑ Wandel 1987, p. 26.

- ↑ Leutner 1987, pp. 25/26; Change 1987, p. 26.

- ↑ Kristeva 1976, pp. 63-69.

- ↑ Linck 1990, p. 16 ff.

- ↑ Wandel 1987, p. 27.

- ↑ Leutner 1987, p. 27.

- ↑ Linck 1990, p. 10.

- ↑ Linck 1990, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ a b Hemm 1996, pp. 6/7.

- ↑ According to Hemm 1996, p. 24: The first girls' schools were established between 1844 and 1860 in Ningbo, Shanhai, Beijing, Fuzhou, Canton, Amoy

- ↑ According to Hemm 1996, p. 24: 1907 the first Chinese women went abroad to study

- ↑ Croll 1977, p. 9.

- ^ A b Bernice June Lee: The Change in the Legal Status of Chinese Women in Civil Matters from Traditional Law to the Republican Code . Sydney 1975. Referred to in: Leutner 1987.

- ↑ Chen Hwei-syin: Changes in Marriage and Family-Related Laws In Taiwan: From Male Dominance to Gender Equality , In: Lin Wei-hung, Hsieh Hsiao-chin: Gender, Culture & Society: Women's Studies in Taiwan. Ewha Womans University Press, Seoul 2005, pp. 396-402.

- ↑ Hemm 1996, p. 28.

- ↑ Wang Shaolan: Education and Employment of Women in China. In: Women and responsibility in the cultures of the countries of Africa and Asia. Verlag für Interkulturelle Kommunikation, Göttingen 1994, ISBN 3-88939-278-4 , p. 184 (their estimate of the illiteracy rate for 1949 is around 90%).

- ↑ Claudie Boryelle: Half of Heaven. Women's emancipation and child-rearing in China. Wagenbach, Berlin 1973, ISBN 3-8031-1050-5 , pp. 120-128; but also compare "Kinhua" 1969 and tendencies in Croll 1977, Leutner 1987, Wang 1994, Hemm 1996.

- ↑ "Kinhua". Women's Liberation in China. Roter Stern publishing house, Frankfurt 1969.

- ↑ Leutner 1987, pp. 25/26.