Nataraja temple

The Nataraja Temple (also Sabhanayaka Temple ) is a Hindu temple in the city of Chidambaram in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu . It is consecrated to Nataraja , a manifestation of the god Shiva . As the place where, according to the myth, Shiva as "King of the Dance" is said to have performed his cosmic dance, the Nataraja Temple is one of the most important Shivaite shrines in India. Chidambaram seems to have been a religious center early on and is mentioned in poetry from the 7th century. In its current form, the Nataraja Temple essentially dates from the late period of the Chola dynasty (11th – 13th centuries) with some additions from the Pandya and Vijayanagar times (13th – 16th centuries).

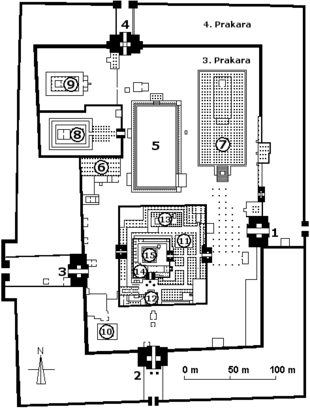

The Nataraja Temple is an excellent example of Dravidian temple architecture . As is characteristic of this architectural style, the temple has a rectangular floor plan and is built according to geometric principles. The temple complex, which is very extensive with over 15 hectares, consists of four concentric areas that are built around the main shrine dedicated to the god Nataraja. The temple complex also includes numerous other components, including secondary shrines, several large temple halls, a temple pond ( pushkarini ) and four towering gate towers ( gopurams ).

history

The Nataraja Temple is a grown building complex with components of very different ages, some of which can be rebuilt several times. Therefore it is often very difficult to determine the age of the respective building parts. No part of the temple can be dated with certainty before the time of the late Chola kings (1070–1279). However, it can be assumed that the origins of the main shrine, for example, go back further into the past. The early history of the temple of Chidambaram is largely in the dark. What is certain is that the sanctuary already existed at the time of the poets Appar , Sambandar and Sundaramurti , who sang Shiva's dance in Tillai (the old name Chidambarams) in their devotional Tevaram hymns in the 7th and 8th centuries .

The Chola kings, who ruled over large parts of southern India between the 9th and 13th centuries, are mainly responsible for the construction of the Nataraja Temple . The Cholas made Nataraja their family deity and began promoting the temple of Chidambaram. King Aditya I (r. 871–907) or his son Parantaka I (r. 907–955) had the roof of the shrine coated with gold which the Cholas had accumulated during their campaigns. Rajaraja I. (r. 985-1014), at the time of which the Chola Empire reached the height of its power, neglected the Nataraja Temple and instead had the Brihadisvara Temple built in the capital Thanjavur as a sign of his imperial rule. His successor Rajendra I (r. 1014-1044) moved the capital to Gangaikonda Cholapuram and also built a large temple there. It was not until Kulottunga I (ruled 1070–1120) that the Chola kings became interested in the Nataraja temple again. The late Chola kings chose Chidambaram as their coronation site and sometimes seem to have held residence in the temple for a long time. Most of the temple complex as it exists today was created under the rule of Kulottunga and his successors in the 12th century.

With the decline of the Chola Empire in the 13th century, Chidambaram came under the influence of local rulers as well as the Pandya kings residing in Madurai , who caused some renovations in the Nataraja temple. After a brief Muslim interlude, Chidambaram came under the rule of the Vijayanagar empire like all of southern India at the end of the 14th century . While the kings of Vijayanagar undertook major temple construction projects in other places, they only initiated minor construction works in the Nataraja temple. In the course of the 18th century, the colonial powers Great Britain and France repeatedly used the well-fortified Nataraja Temple as a fortress during the Carnatic Wars , in which they fought for supremacy in southern India. Because of the chaos of war, the image of the god Nataraja was brought to a safe place in Tiruvarur and only returned to Chidambaram in 1773. With the beginning of the British colonial period , the promotion of the Nataraja Temple by royal rulers ended. On the other hand, from the 19th century on, it was above all wealthy traders from the Nattukottai Chettiars caste who made money around the temple and financed numerous smaller renovation and maintenance measures. The last major renovation of the temple culminated in a major rededication ceremony ( mahakumbhabhisheka ) in 1987 .

location

The Nataraja Temple is not only the towering attraction of the otherwise rather insignificant 60,000-inhabitant city of Chidambaram, but also forms the center of the place. The city plan of Chidambaram is based on the Nataraja Temple: Several rectangular road rings surround it following its outlines, cross streets run axially towards the entrance gates. The innermost of the road rings is formed by the streets East Car Street , South Car Street , West Car Street and North Car Street . The streets are noticeably wide at 18 meters. They are used at the temple festivals for the large processions. The name Car Street comes from the large temple wagons (English: car ) that are pulled around the temple and parked for the rest of the time on East Car Street opposite the east entrance of the temple. The houses between Car Street and the temple wall form the residential area of the temple's priests. With its city plan built concentrically around the Nataraja temple, Chidambaram embodies the classic type of the south Indian temple city.

architecture

overview

The Nataraja Temple comprises an extensive complex with a rectangular floor plan of around 450 × 330 meters and an area of over 15 hectares. The center of the temple is the Holy of Holies with the image of Natarajas. Four wall rings, which surround the central sanctuary, divide the temple complex into four concentric areas ( called prakaras ). The closer you get to the center, the more sacred the area becomes. For example, temple visitors have to take off their shoes at the third enclosure wall, photography is prohibited from the two innermost areas, and finally only the temple priests are allowed to enter the Nataraja shrine.

The outermost prakara in the narrower sense does not belong to the actual temple. It consists of gardens and palm groves that are not open to the public. The outermost surrounding wall has a simple entrance gate in each of the four cardinal directions, from which a passage leads to the third prakara. The four gates in the third enclosure wall are each crowned by a massive gopuram (1–4). The third prakara is not completely rectangular, but has a bulge in the northwest corner. It consists mostly of paved courtyard areas and houses the temple pond (5), two large pillared halls - the hundred pillar hall (6) and the thousand pillar hall (7) - as well as side shrines for Shiva's wife Shivakamasundari (8) and his sons Murugan (9) and Ganesha (10). The area within the two innermost wall rings is largely covered. Here numerous components combine to form an angled and difficult-to-see complex. The second prakara includes numerous colonnades and corridors, two temple halls - the Deva Sabha (11) and the Nritta Sabha (12) - the Mulasthana shrine (13) and other smaller shrines. In the innermost prakara are the Govindaraja shrine (14) and finally the most holy place of the temple, the Chit Sabha and the Kanaka Sabha (15) directly connected to it.

The Nataraja Temple represents the Dravida style , the predominant direction of temple architecture in South India. Particularly characteristic are the striking gopurams and the plan based on geometrical principles concentric around the main shrine and oriented towards the cardinal points. However, the Nataraja temple does not have the same strict symmetry as the temples of Madurai or Srirangam . So the gopurams are not in a line, but are laterally offset from one another.

Shrines

The Holy of Holies of the Nataraja Temple is named Chit Sabha and houses a bronze statue of Shiva about one meter high in its anthropomorphic form as Nataraja ("King of Dance"). It is already mentioned in the Tevaram hymns under the Tamil name of Chitrambalam (“small hall”) . The name was later reinterpreted in Sanskrit and changed to Chit Sabha ("Hall of Consciousness"). Even if it cannot be determined exactly how old the Chit Sabha is in its current building structure, it seems to go back to a very old shrine. From an architectural point of view, the Chit Sabha is very unusual: it has a rectangular floor plan of less than 8 × 4 meters, is made of wood and has a gilded roof whose arched shape is reminiscent of a thatched roof; the statue of Natarajas also faces south. Usually, however, in the Dravida style, shrines are built of stone, square, covered by a pyramidal vimana and facing east. The Chit Sabha stands on a platform about one meter high and opens to the south to the directly attached Kanaka Sabha ("golden hall"), which serves as a kind of vestibule to the main shrine. The roof of the Kanaka Sabha has the same shape as that of the Chit Sabha, but is copper-colored. A double colonnade surrounds Chit Sabha and Kanaka Sabha.

The second most important shrine of the Nataraja Temple is dedicated to Shiva's wife Shivakamasundari (a Tamil nickname Parvatis ). The Shivakamasundari shrine dates from the Chola period. It is located in the third prakara and has its own surrounding wall with a two-story colonnade. In front of the shrine is a columned hall from the 17th century, the roof of which is decorated with rich paintings. Also in the courtyard of the third prakara are two side shrines for the sons of Shiva and Parvati, Subramanya (Murugan) and Vinayaka (Ganesha). The Murugan Shrine dates from the Pandya period of the 13th century and is characterized by its ornate pillars.

In addition to his figure as Nataraja, Shiva is worshiped in the Mulasthana shrine in the form of a non-pictorial linga . The shrine is located in the second Prakara north of the main shrine and was probably built in the 13th century. In the innermost prakara in the immediate vicinity of the Nataraja shrine there is a shrine for Govindaraja ( Vishnu ), completed in 1539 . There are also numerous other, less important shrines dedicated to other manifestations of Shiva and other deities, as well as the 63 Nayanmars , the hymn poets venerated as Shivaite saints in Tamil Nadu.

Temple halls

The complex of the Nataraja temple includes several temple halls. In the second prakara, the Nritta Sabha (“dance hall”) is in line with the Chit Sabha. From an architectural point of view, it can be assigned to the Chola period, but there may have been a shrine in its place earlier, possibly dedicated to the goddess Kali . With its 54 richly sculptured stone pillars and the decorations in the form of wagon wheels and horses on the outer walls, which replicate a temple chariot ( Ratha ), the Nritta Sabha is one of the most artistic buildings in the temple complex. Also in the second prakara, east of the main shrine, is the Deva Sabha (“hall of the gods”). The spacious hall has an area of around 15 × 15 meters, reaches a height of 19.5 meters and is also covered by a high vaulted roof. It is used to store the bronze processional statues of the gods, which are carried out during the temple festivals, and as a meeting hall for the priests.

In the courtyard in the third prakara there are two large pillared halls, the Hundred Pillar Hall and the Thousand Pillar Hall. The hundred pillar hall is approx. 48 × 35 meters and is located in the western area against the third surrounding wall and the wall of the Shivakamasundari shrine. The thousand-pillar hall is free-standing in the northeast area of the temple area and is the largest of the temple halls with 106 × 58 meters. It is also known as Raja Sabha ("King's Hall") because it was originally built in the mid-12th century as an audience hall for the Chola kings. Today they are used for certain ceremonies at the great temple festivals.

Temple pond

Like almost all large Tamil Nadu temples, the temple of Chidambaram has a temple pond ( pushkarini ). This is known as the Shivaganga pond, after the goddess Ganga , the personification of the river Ganges . It is a rectangular basin measuring 105 × 61 meters in the courtyard area of the third prakara . During the Chola period, the pond was bordered with steps leading to the water ( ghats ) and a colonnade. The Shivaganga pond is used by believers as a place for ritual ablutions. It is one of a total of ten holy bathing places ( tirthas ) in Chidambaram. This includes the Paramananda Kupa fountain near the Chit Sabha, from which the water for the rituals in the Holy of Holies comes, as well as other ponds in and around Chidambaram and finally the nearby sea.

Gopurams

The most striking structural element of the Nataraja Temple are the gate towers ( gopurams ) , which are typical of the Dravida style, built on a rectangular floor plan . These four towers, visible from afar, in the third enclosure wall, reach heights of up to 42 meters. The oldest of the Gopurams is the West Gopuram (around 1175), followed by the East (around 1200) and South Gopuram (1250). The North Gopuram was probably started in the 13th century but wasn't completed until the 16th century under the Vijayanagar ruler Krishnadevaraya . However, all four gopurams follow the same construction plan: They consist of a massive two-story stone base, a seven-story pyramidal superstructure and a roof attachment. The pedestals contain niches with statues of various manifestations of Shiva, other gods and mythical figures. In the East and West Gopuram there are relief representations on the sides of the gate passage, which show the 108 dance positions of classical Indian dance . The brightly painted superstructures are adorned with stucco figures. The main entrance to the temple is through the East Gopuram. Here is a temple elephant that blesses visitors by touching their trunk for a donation.

Inside the temple there are further, significantly lower gopurams. The second enclosure wall has a gopuram in the west and east, which is in line with the Nataraja shrine. In the innermost enclosure wall there are three gate towers: one in the south and one in the east, both also oriented towards the main shrine, and another in the east, which is in line with the Govindaraja shrine. The Shivakamasundari Shrine also has an East Gopuram in its enclosure wall.

Religious meaning

myth

Like almost every important South Indian temple, the temple of Chidambaram also has its own local legend, which tells the history of the temple's founding. It is handed down in two versions: Im on Sanskrit written Chidambaramahatmya from the 12th or 13th century in a Tamil paraphrase entitled Koyil Purana , the author Umapati Shivacharya about a century later wrote.

The Chidambaramahatmya relates: A wise man went to a forest of Tillai trees in Chidambaram to practice asceticism and there worshiped a linga on the bank of a pond by decorating it with flowers. He asked Shiva to give him the claws of a tiger so that he could climb the trees and pick the best flowers there to worship his master. Shiva granted the wise one this request, and since then he has been called vyaghrapada , tiger foot. Shiva, in the form of an ascetic, went with Vishnu , who has assumed the form of a beautiful woman, to the Daruvana forest, where a host of seers ( rishis ) lived. While Vishnu bewitched the Rishis, Shiva seduced their wives. The seers became angry and one after the other chase a tiger, a snake and an antelope on Shiva to kill him. But Shiva defeated the animals and wore their skin as an ornament. Shiva also defeated a dwarf demon and began to dance on his back. Vishnu, who had followed the dance, reported what he had seen to the serpent Shesha . Shesha wished to see Shiva's dance, so he incarnated in half-human form as Patanjali and went to Chidambaram. There Shiva performed his dance in front of Vyaghrapada, Patanjali and a crowd of three thousand Brahmins . Later a Bengali king named Hiranyavarman came to Chidambaram. After a bath in the pond of the Tillai forest, he received a golden body and became a worshiper of Shiva. Hiranyavarman built a temple in Chidambaram and brought back the three thousand priests who had in the meantime gone to northern India.

Shaivism

The temple of Chidambaram is a Shivaite temple ( Shivaism is one of the three main currents of Orthodox Hinduism , along with Vishnuism and Shaktism ). The main deity of the temple is Shiva in his form as Nataraja ("King of the Dance"). Chidambaram is considered to be the place where Nataraja is said to have performed his cosmic "Dance of Bliss" ( Ananda Tandava ), which symbolizes the process of creation, destruction and re-creation of the universe. The temple of Chidambaram is the only Hindu temple whose main deity is Nataraja. Nataraja bronzes can also be found in side shrines in numerous other South Indian Shiva temples, but Shiva is always embodied in the main shrine as a non-pictorial linga . A group of five temples in Tamil Nadu, known as the "five dance halls" ( Pancha Sabha ), is associated with the Nataraja cult . These include the Nataraja Temple of Chidambaram, the Minakshi Temple of Madurai and the temples of Tirunelveli , Tiruvalangadu and Courtallam . While the other four temples each embody one aspect of Shiva's dance (creation, maintenance, veiling and redemption), in his dance in Chidambaram all these deeds are present at the same time. As the place of Shiva's cosmic dance, Chidambaram is one of the most sacred places in India. South Indian Shivaites consider the Nataraja Temple to be the most important Shiva sanctuary and simply refer to it as " the temple".

In the main shrine of the Nataraja Temple, the so-called Chidambara Rahasya (“Secret of Chidambaram”) is venerated. In an empty room separated by a curtain, Shiva should manifest in the invisible ether ( akasha ). The Nataraja temple is one of the "five-element temples" ( Pancha Bhuta Sthalangal ), in which Shiva is worshiped as a manifestation of the elements fire, earth, water, wind and ether (understood as an element in Hinduism).

Vishnuism

Although the Nataraja temple is a Shivaite temple, it also houses a shrine for Vishnu , the main god of Vishnuism, who is worshiped here under the name Govindaraja. Thanks to the Govindaraja shrine, Chidambaram is one of the 108 holy places ( Divya Desams ) of Tamil Vishnuism under the name Tiruchitrakudam . The shrine was built in 1539 during the Vijayanagar period. The client, King Achyutadevaraya , appealed to "restore" the veneration of Vishnu. In fact, the fact that Chidambaram was sung about by two Vishnuit hymn poets in the 7th and 8th centuries suggests that there was a Vishnu cult there in earlier times. It is reported that King Kulottunga II (1133–1150) had a portrait of Vishnu sunk in the sea near Chidambaram. Contemporary European reports from the 16th century report bitter disputes over the construction of the Govindaraja shrine, during which Shivaite priests are said to have thrown themselves from the top of a gopuram in protest.

Religious life

Priests and temple administrators

The priests of the Nataraja Temple belong to the dikshitar community, which has around 1,000 members and is based in Chidambaram. Like all Hindu temple priests, the dikshitars belong to the Brahmin caste , but they form their own, endogamous community, which differs greatly from the temple priests of the other Shiva temples in Tamil Nadu, all of which belong to the Adishaiva subcaste. The approximately 200 married dikshitar men have undergone a special initiation that enables them to serve as priests in the temple. The Dikshitars trace their origins back to the community of the "three thousand" ( Muvayiravar ), which the legendary King Hiranyavarman is said to have brought to Chidambaram according to the myth. Outwardly, the priests can be recognized by their traditional clothing and their hair bun on the left side of the head.

While the priesthood in other temples is strictly hierarchical, the dikshitar priests are organized in an egalitarian manner and take turns performing the various rituals. Since only married men can serve as priests, the children of the dikshitars are married off very young - boys around the age of twelve, girls around the age of seven. The dikshitar community expects all of its male members to become priests and only in exceptional cases allows them to accept work outside of Chidambaram. This also results in the extraordinarily high number of priests who serve in the Nataraja Temple - only around 60 priests work in the similarly large Minakshi Temple in Madurai.

Traditionally, the Nataraja Temple was run by a democratic council made up of two hundred dikshitar priests. In this it differed from the other great temples of Tamil Nadu, which are administered by the state. Since India's independence, the state government has tried several times to bring the Nataraja Temple under its control. Two court rulings in 1954 and 1981 granted the dikshitars the right to manage the temple themselves. In February 2009 the Tamil Nadu Supreme Court transferred control of the Nataraja Temple to the state-owned Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Administration Department after a protracted legal battle . In January 2014, however, the Indian Supreme Court revoked the previous decision and transferred the temple administration back to the dikshitar.

Rituals

The elaborate rituals that are performed daily by the priests of the Nataraja Temple follow a precisely defined sequence. During the temple's opening hours from 6 a.m. to 1 p.m. and from 5 p.m. to 10 p.m., six pujas are held at the main shrine every day . During the first puja, around 6:30 in the morning, a portrait of Shiva's feet is brought back to the main shrine from his “bedchamber”, a separate room in which it was kept overnight. The rituals that follow during the day include washing the images of the gods and waving camphor lights in front of the deity. The temple visitors gather in front of the shrine to see the deity ( Darshana ). In the evening the image is brought back into the room in order to ceremonially bed the deity to sleep. Similar, but simpler rituals take place in the side shrines.

Unlike the other Shiva temples in Tamil Nadu, the priests in Chidambaram do not follow the Shivaite ritual manuals, the Shaiva Agamas , but their own manual, which the Sanskrit grammarian Patanjali wrote in the 2nd century BC. Should have written down. According to the priests, the rite they practiced ultimately goes back to the Vedas , the oldest sacred scriptures in Hinduism .

Temple festivals

Chidambaram celebrates several temple festivals every year. The most important takes place in the Tamil month of Markali (December / January). The ten-day festival begins with the flag-raising ceremony and includes several processions in which the faithful carry images of gods through the city. The festivities culminate on the ninth day, when Nataraja leaves his sanctuary and joins the procession. While the main idols of a Hindu temple are usually immobile and special processional figures are used for the temple festivals, in Chidambaram the bronze image of Natarajas is carried out of the holy of holies and pulled around the temple on a large chariot ( ratha ). On the tenth and final day, the deity is anointed in the great abhisheka ceremony. These days are the highlight of the year in Chidambaram and regularly attract up to 200,000 visitors.

A second big temple festival takes place in the month of Ani (June / July). It also lasts ten days and is similar to the Markali festival. At another festival in the month of Masi (February / March) the portrait of Natarajas is brought to the seashore.

literature

- James Coffin Harle: Temple Gateways in South India. The Architecture and Iconography of the Chidambaram Gopuras. M. Manoharlal Publ., New Delhi 1995, ISBN 81-215-0666-2 (reprint of the Oxford 1963 edition).

- Vivek Nanda (Ed.): Chidambaram. Home of Nataraja. Mary Publ., Mumbai 2004, ISBN 81-85026-64-5 .

- Balusubrahmanyam Natarajan: Tillai and Nataraja. Mudgala Trust, Madras 1994.

- David Smith: The dance of Siva. Religion, art and poetry in South India (Cambridge Studies in Religoud traditions; Vol. 7). Foundation Books, New Delhi 1998, ISBN 81-7596-042-6 (reprinted from Cambridge 1996 edition).

- Paul Younger: The home of dancing Śivaṉ. The traditions of the Hindu temple in Citamparam. OUP, New York a. a. 1995, ISBN 0-19-509533-2 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ For the history of the construction of the Nataraja Temple see u. A. Paul Younger: The home of dancing Śivaṉ. The traditions of the Hindu temple in Citamparam. New York et al. a. 1995, pp. 81-117.

- ↑ Gerd JR Mevissen: Chola Architecture and Sculpture at Chidambaram. In: Vivek Nanda (ed.): Chidambaram. Home of Nataraja. Mumbai 2004, p. 83.

- ↑ Younger 1995, p. 83.

- ↑ Younger 1995, p. 94 f.

- ↑ Younger 1995, p. 40.

- ↑ Younger 1995, p. 146.

- ↑ a b c Numbers according to Vivek Nanda: Chidambaram: A Ritual Topography. In: Vivek Nanda (ed.): Chidambaram. Home of Nataraja. Mumbai 2004, pp. 8-21. There are different sizes.

- ↑ Younger 1995, pp. 84-87.

- ↑ Younger 1995, p. 89 f.

- ↑ Mevissen 2004, p. 83 f.

- ↑ Mevissen 2004, p. 88.

- ↑ Younger 1995, p. 163.

- ↑ Summary based on Hermann Kulke : Cidambaramahatmya. An examination of the religious history and historical background for the emergence of the tradition of a south Indian temple city. Wiesbaden 1970, pp. 1-29.

- ↑ John Guy: The Nataraja Murti and Chidambaram: Genesis of a Cult Image. In: Vivek Nanda (ed.): Chidambaram. Home of Nataraja. Mumbai 2004, p. 73.

- ↑ Saskia Kersenboom: Where Shiva dances. In: Johannes Belz (Ed.): Shiva Nataraja. The cosmic dancer. Zurich 2008, p. 63.

- ^ David Smith: The dance of Siva. Religion, art and poetry in South India. Cambridge et al. a. 1996, p. 1.

- ↑ B. Natarajan: Chidambara Rahasya: The 'Secret' of Chidambaram. In: Vivek Nanda (ed.): Chidambaram. Home of Nataraja. Mumbai 2004, pp. 55-59.

- ↑ Younger 1995, p. 111 f.

- ^ B. Natarajan: The City of the Cosmic Dance. Chidambaram. New Delhi 1974, p. 59.

- ↑ Younger 1995, p. 13.

- ↑ Younger 1995, p. 22 ff.

- ^ CJ Fuller: Servants of the Goddess. The Priests of a South Indian Temple. Cambridge et al. A. 1984, p. 25.

- ↑ Younger 1995, p. 19 f.

- ↑ Younger 1995, p. 148.

- ↑ HR and CE starts cleaning up Chidambaram temple premises . In: The Hindu . dated February 7, 2009; and Court order ends an era in Chidambaram temple . In: The Hindu. dated February 8, 2009.

- ↑ Dikshitars' right to manage Natarajar temple cannot be taken away: SC . In: The Hindu. from January 7, 2014.

- ↑ Younger 1995, pp. 24-28.

- ↑ Younger 1995, p. 24.

- ↑ Younger 1995, pp. 54-67.

- ↑ 2 lakh devotees throng Chidambaram ( Memento of the original from March 31, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . In: The Hindu. dated December 31, 2001.

Web links

- Nataraja Temple site

- Bernhard Peter: The Nataraja Temple of Chidambaram

- Alan Croker: Temple Architecture in South India. In: Robert Irving (Ed.): The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand, No. 4, June 1, 1993, pp. 109–123 (PDF, 345 kB)

- TempleNet: Chidambaram (English)

Coordinates: 11 ° 23 ′ 58 ″ N , 79 ° 41 ′ 36 ″ E