New poems (Rilke)

The New Poems are a two-part collection of Rainer Maria Rilke's poems .

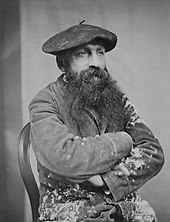

The first, Elizabeth and Karl von der Heydt dedicated band originated from 1902 to 1907 and appeared in the same year in Insel Verlag in Leipzig , the second, Auguste Rodin its intended (the New Poems another part) was completed in 1908 and published by the same publisher.

Along with Malte Laurids Brigge, the collection is considered to be the main work of his middle creative phase, which clearly stands out from his previous and subsequent production. It marks a turn from the emotional poetry of ecstatic subjectivity and inwardness , such as that predominates in his three -part book of hours , to the more objective language of thing poems . With this new poetic orientation, which was mainly influenced by Rodin's visual arts , Rilke is considered one of the most important poets of literary modernism .

With the exception of eight poems written on Capri , Rilke wrote most of them in Paris and Meudon . At the beginning of both volumes, he placed Early Apollo and Archaic Torso, Apollo's verses about sculptures of the poet god .

background

Since the collection lacks a comprehensive context of meaning as well as an overarching overall concept, there is no poetry cycle in the strict sense; On the other hand, it should not be concluded that the composition is arbitrary, because with all the diversity of forms and genres, everything is permeated by a consistent design principle - the relation to things in lyrical speaking, which is linked to the experience of perceived reality.

As with the Dinglyric from the Parnassians to Eduard Mörike and Conrad Ferdinand Meyer , which, unlike romantic poetry , is not based on music but on the fine arts, this point of reference can also be felt in Rilke's poems; first in the outstanding figure of the sculptor Rodin, about whom he first wrote a monograph and whose private secretary he became, later in the encounter with the work of Paul Cézanne , for example during the Paris Cézanne exhibition of 1907.

Origin and language crisis

The poems reflect impressions that Rilke experienced in this environment, experiences that he entrusted to numerous letters - for example to Lou Andreas-Salomé or Clara Westhoff - in great detail and from which the influence on his own, on the things of reality oriented art emerges. They are also at the end of a long development process: a year after he had finished the monograph on Rodin, he told Lou Andreas-Salomé how desperately he was looking for a technical basis for his art, a tool that would give his art the necessary solidity. He ruled out two possibilities: The new craft should not be the language itself, which could be found in “a better understanding of your inner life”. He also did not want to take the humanistic path of education that Hugo von Hofmannsthal had taken to seek the foundations “in a well-inherited and increased culture”. The poetic craft should rather be seeing itself, the ability "to look better, to look at, with more patience, with more immersion."

Rilke was fascinated by both the precise craftsmanship and the concentration on the object, a way of working that he could often observe at Rodin. The form-bound nature of art and the possibility of using it to show the surface of an object and at the same time to give an idea of its essence are reflected in the two volumes of poetry.

To Lou-Andreas Salomé, he described Rodin as a lonely old man who "stands sunk in himself, full of sap like an old tree in autumn." Rodin has given his heart "a depth and his beat comes from afar as from the middle of a mountain." For Rilke, Rodin's real discovery was the liberation of the surfaces and the, as it were, unintentional design of the sculpture from the forms liberated in this way. He described how Rodin did not follow a leading concept, but masterfully designed the smallest elements in accordance with their own development.

While Rodin closes himself off to the unimportant, he opens up to reality, where "animals and people ... like things touch him." As a constantly receiving lover, nothing escapes him and as a craftsman he has a concentrated "way of looking." It is nothing "Uncertain for him about an object that serves as a model for him ... The thing is determined, the art-thing must be even more definite, removed from all chance, removed from all ambiguity, lifted from time and given space, it has become permanent, capable of eternity. The model seems that art thing is . "

While Rilke had experienced the landscape in Worpswede "as the language for his confessions" and with Rodin got to know the "language of hands", Cézanne finally led him into the realm of colors . The special color perception that Rilke developed especially in France is illustrated by his well-known sonnet Blue Hydrangea , in which he shows the interplay of almost detached, seemingly lively colors.

Rilke's turn to the visual testifies to a low level of trust in language and is related to the language crisis of modernity, which is hinted at in Hofmannsthal's Chandos letter , in which he addresses the reasons for a deep linguistic doubt. The language, according to Rilke, offers "too coarse forceps" to be able to open up the soul; the word could not be “the outer sign” for “our real life”. Like Hofmannsthal, whom he admired, Rilke made a distinction between a poetic-metaphorical language of things and an abstract-rational conceptual language.

particularities

The New Poems show Rilke's great sensitivity for the world of objective reality. The ascetic reference to things in his verses no longer allowed the open-hearted pronunciation of his soul, fine moods and feelings and the form of prayer , which was still so clear in the book of hours , receded.

Descriptive in the initial position, the boundary between the viewer and the object dissolves while looking and creates new connections. With this mysticism of things , however, Rilke did not intend to intoxicate the clarity of consciousness , especially since he often made use of the (“conscious”, architectural planning presupposed) form of the sonnet, whose caesuras are, however, covered over by the musical language. In contrast to Mörike and Conrad Ferdinand Meyer - (his Roman fountain is paradigmatic ) - Rilke did not simply want to describe objects or to objectify the moods they evoke; Rather, the thing should be charged with a special meaning, as it were, and thus detached from conventional references to space and time. This is evidenced by the lines of the rhyming poem Die Rosenschale , with which the first part ends: “And the movement in the roses, see: / gestures with such a small deflection angle / that they remained invisible, their / rays did not diverge into space . "

As he described in a short essay Ur-Gerärm published in 1919 , he wanted to use art to expand the senses in order to give things back their own value, their "pure size" and to remove them from the recipient's rational availability . He believed in a higher overall context of all beings , which could only be reached through the art that transcended the world: the “perfect poem” could “only arise under the condition that the world attacked with five levers at the same time under a certain aspect on the supernatural Level appear which is that of the poem. "

Meaning and reception

After research had neglected the Rilke collection for a long time compared to his later works such as the Duineser Elegies or the Sonnets to Orpheus , a counter-movement has emerged in the last few decades. Within his oeuvre , the New Poems were now regarded as his most important contribution to modern literature and received the most intense attention. They document his ideal of thing poetry, which mainly relates to (external) objects, works of painting , sculpture and architecture , to animals from the Parisian Jardin des Plantes and landscapes.

In poems such as the Panther , his most famous work, or the Archaic Torso of Apollo , Rilke approaches the ideal of this genre most clearly. In this sonnet , what is seen is transformed into a transcendent symbol that encloses the observing subject and the seen object: Although the torso lacks the head, the whole statue glows from the inside, shines like a star towards the viewer and leads to an epiphanic Damascus experience : "... because there is no place that does not see you. You have to change your life."

The New Poems also attracted opposing interpretations. Part of the research saw in them the reconciling interpretation of human existence or referred - according to Walther Rehm - to their “icy glory.” “All those things, the fountains and marble carts, the stairs of the orangery , the courtesan and the alchemist , the beggar and the saint - neither knows deeply about the other. All of them stand unrelated as if by chance and spared, like statues or sculptures, lonely next to each other, in the artfully arranged room of this collection of poems, almost like in a museum. "

Since Rilke was concerned not with the objects as such, but with their representation , it made sense to interpret his poetry phenomenologically . Above all, Käte Hamburger pointed to a connection to the philosophy of Edmund Husserl , who dealt with this question in his 1907 lecture Thing and Space . Theodor W. Adorno also dealt with Rilke in the margin and was bothered by the "talkative adornment" and the tendency to give in to verse and rhyme, which distinguishes Rilke from the more rigid Stefan George . The dialectic of particular and universal concerns for Adorno also the lyrical language: As much as the good poem expresses subjective and free himself of the language conventions of society, so little the universal is but eradicated from him.

With the “ idiosyncrasy of the lyrical spirit against the overwhelming power of things”, the poet reacts to “the reification of the world, the rule of goods over people”, which can also be found in Rilke's poetry. Adorno disparagingly referred to its dingy as a “thing cult”, which belongs in this “spell” and with which he tries “to incorporate and dissolve foreign things in the subjective pure expression, to credit them metaphysically with their foreignness.” The “aesthetic weakness of this Thing cults, the secretive gesture, the mixing of religion and applied arts testify to the real reification that can no longer be gilded by any lyrical aura .

Walther Rehm, in particular, used the interpretation term “thing mysticism” to describe Rilke's relationship to things. Rehm started from a tradition of the experience of things that began with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and culminated in Rilke's poetry, which gave the thing a special and independent quality. His being related to God refuses to allow useful functional access and only reveals himself in mindful looking.

The concept of the thing refers to the entire area of beings , from the objects of daily life to landscapes, people and moods . Rilke's worship of things thus becomes thing mysticism, in that things magically become independent and are redeemed when man recognizes their essence. The poet, endowed with high receptivity , lives in the center of things, transforms them and also announces their end. Rilke's Dinglyrik is "death poetry".

Poems included

literature

- Wolfgang G. Müller in: Rilke manual, life - work - effect. Ed .: Manfred Engel with the collaboration of Dorothea Lauterbach, Metzler, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-476-02526-5 , pp. 296-318.

- Meinhard Prill, in: Rainer Maria Rilke, Neue Gedichte , Kindlers Neues Literatur-Lexikon, Volume 14, Kindler Verlag, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-463-43014-2 , pp. 146–148

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wolfgang G. Müller, in: Rilke manual, Life - Work - Effect, Metzler, Ed. Manfred Engel, Stuttgart 2013, p. 296

- ↑ Wolfgang G. Müller, in: Rilke manual, Life - Work - Effect, Metzler, Ed. Manfred Engel, Stuttgart 2013, p. 312

- ↑ Quoted from: Antje Büssgen, in: Rilke-Handbuch, Leben - Werk --ffekt, Metzler, Ed. Manfred Engel, Stuttgart 2013, p. 134

- ↑ Meinhard Prill, in: Rainer Maria Rilke, Neue Gedichte, Kindlers Neues Literatur-Lexikon, Vol. 14, Munich, 1991, p. 147

- ^ Rainer Maria Rilke, letters in two volumes, first volume, 1896 to 1919, published by Horst Nalewski, Insel Verlag Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig 1991, p. 148

- ↑ Manfred Koch, in: Rilke manual, Life - Work - Effect, Metzler, Ed. Manfred Engel, Stuttgart 2013, p. 494

- ^ Rainer Maria Rilke, letters in two volumes, first volume, 1896 to 1919, published by Horst Nalewski, Insel Verlag Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig 1991, p. 148

- ^ Rainer Maria Rilke, letters in two volumes, first volume, 1896 to 1919, published by Horst Nalewski, Insel Verlag Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig 1991, p. 149

- ↑ Antje Büssgen, in: Rilke manual, Life - Work - Effect, Metzler, Ed. Manfred Engel, Stuttgart 2013, p. 136

- ↑ Quoted from: Antje Büssgen, in: Rilke-Handbuch, Leben - Werk --ffekt, Metzler, Ed. Manfred Engel, Stuttgart 2013, p. 136

- ^ Gero von Wilpert, Lexikon der Weltliteratur, Neue Gedichte, Alfred Kröner Verlag, p. 959

- ^ Rainer Maria Rilke, Die Rosenschale , in: Complete Works, First Volume, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1955, p. 553

- ↑ Quoted from: Meinhard Prill, Rainer Maria Rilke, Neue Gedichte, Kindlers Neues Literatur-Lexikon, Vol. 14, Munich, 1991, p. 147

- ↑ Meinhard Prill, in: Rainer Maria Rilke, Neue Gedichte, Kindlers Neues Literatur-Lexikon, Vol. 14, Munich, 1991, p. 147

- ^ Rainer Maria Rilke, Archaïscher Torso Apollos, in: Complete Works, First Volume, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1955, p. 557

- ↑ Quoted from: Meinhard Prill, in: Rainer Maria Rilke, Neue Gedichte, Kindlers Neues Literatur-Lexikon, Vol. 14, Munich, 1991, p. 147

- ↑ Wolfgang G. Müller, in: Rilke manual, Life - Work - Effect, Metzler, Ed. Manfred Engel, Stuttgart 2013, p. 304

- ↑ Sven Kramer, Poetry and Society . In: Richard Klein, Johann Kreuzer, Stefan Müller-Doohm (eds.): Adorno manual. Life - work - effect. Metzler, Stuttgart 2011, p. 201.

- ^ Theodor W. Adorno, Speech on Poetry and Society, Collected Writings, Volume 11, p. 52

- ^ Hennig Brinkmann : Dingmystik. In: Historical Dictionary of Philosophy , Volume 2, p. 255.