Orford Castle

Orford Castle is a castle in the village of Orford , 20 km northeast of Ipswich in the English county of Suffolk . From there you can see the Orford Ness . The castle was built for King Henry II from 1165 to 1173 to secure royal power in the region. The well-preserved Keep , which the historian R. Allen Brown describes as "one of the most remarkable in England", shows a unique construction that is probably based on Byzantine models. It stands in the earth-covered remains of the outer fortifications.

history

12th Century

Before Orford Castle was built, the Bigod family dominated Suffolk. She held the title of Earls of Norfolk and she owned the most important castles in the area, such as Framlingham Castle , Bungay Castle , Walton Castle and Thetford Castle . Hugh Bigod belonged to a group of dissenting barons during the reign of Stephen I during the anarchy and Henry II wanted to extend the royal influence again over the entire region. Henry confiscated the four castles from Hugh Bigod, but returned Framlingham and Bungay to him in 1165. Henry then decided to have his own royal castle built in Orford near Framlingham. Construction began in 1165 and was completed in 1173. The Orford site was about two miles from the coast, was level, somewhat marshy, and sloped gently towards the River Ore , about half a mile away .

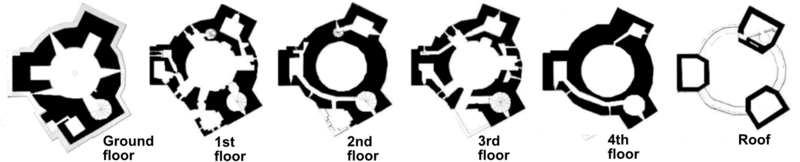

The construction of the keep was unique in England and it was later described by the historian R. Allen Brown as "one of the most remarkable donjons in England". The 27 meter high, central tower with a diameter of 15 meters was circular and had three rectangular towers attached to the perimeter, which towered over the central tower. The tower was based on precise proportions; its various dimensions followed the ratio 1: 1.4142 (1: root 2) found in many contemporary English churches. Most of the interior walls consist of high-quality ashlar masonry with 1.7 meter wide staircases. Originally, the roof of the donjon over the upper hall was dome-like with a tall tower above it.

The keep was surrounded by a curtain wall and probably had four flanking towers and a gatehouse , which enclosed a relatively small castle courtyard. These external fortifications were the actual protection of the castle, not so much the keep itself. The nearby marshland was drained and the village of Orford was given a protected harbor. The construction of the castle, including the moat, palisade and stone bridge, cost £ 1,413; the work was probably carried out by the builder Alnoth . Some of the timbers were brought to the site from Scarborough and the stone carvings were made from limestone from Caen in Normandy . The remaining building blocks consisted of locally broken sedimentary rocks and coral limestone, as well as Northamptonshire limestone .

The construction of the keep has generated a lot of historical interest. Traditional explanations for its unusual floor plan are that the castle was a military transitional structure that combined both circular elements from later castles and rectangular buttresses from earlier Norman fortifications. The more recent teaching criticizes this explanation. The construction of the keep of Orford is militarily difficult to classify because buttresses created additional blind spots for the defenders, while the chambers and the stairwell in the corners weakened the walls. Rectangular Norman Keeps were still being built after Orford, while Henry II was familiar with completely circular castle floor plans before he had this keep built. A circular keep was z. B. Built in 1146 at New Buckenham Castle in Norfolk . Historians have therefore raised the question of the extent to which the construction of the keep in Orford can be viewed as a real transition construction. Instead, so today's historians believe, this construction was motivated by political symbolism. Heslop believes that the clean, simple elegance of architecture conjured up the image of King Arthur for 12th-century nobles , who at the time was widely believed to have had ties to the Romans and Greeks. The banded, angled details of the keep resembled the Theodosian wall of Constantinople , then an idealized image of imperial power, and the keep as a whole, including the roof, may have been based on a hall that was being built by John II in Constantinople at the time had been.

13th to 19th centuries

By the early 13th century, royal authority in Suffolk was firmly established after Henry II weakened the bigods in the revolt of 1173–1174 . Orford Castle was occupied with a large garrison in this conflict; 20 knights were stationed there alone. After the collapse of the revolt, Henry II ordered the final confiscation of Framlingham Castle. The political importance of Orford Castle decreased after Henry's death in 1189, although the port of Orford increased in importance and at the beginning of the century more goods were handled there than in the more famous port of Ipswich .

During the First Barons' War , the castle was captured by Prince Ludwig of France in 1216 , who, with the support of rebellious barons, claimed the English crown. John FitzRobert was under the young Heinrich III. Governor of the Royal Castle, followed by Hubert de Burgh . Under Edward I a governor from the "Valoines family" was appointed. The office then passed through marriage to Robert d'Ufford , the first Earl of Suffolk , to whom the office was then perpetuated by Edward III in 1336 . was awarded. Orford Castle was no longer a royal castle and passed through the hands of the Willoughby , Stanhope and Devereux families . The Orford settlement, however, went through an economic decline during this period. The Ore estuary silted up and the Orford Ness grew, making it increasingly difficult to enter the port. The volume of trade decreased and with it the importance of Orford Castle as a center of local power.

The castle and the surrounding lands were bought by the Seymour-Conway family in 1754 . At the end of the 18th century only the north wall of the castle courtyard was preserved and the roof and the upper floors of the keep were badly dilapidated. Francis Seymour-Conway , the second Marquess of Hertford , proposed the demolition of the building in 1805. The government stopped him because they saw the keep as an important landmark for ships approaching from the Dutch coast that did not want to run aground on the nearby sandbanks. Francis' son, also called Francis , commissioned restorations in 1831, during which the top floor of the keep was rebuilt and provided with a relatively flat lead roof. In the 1840s, almost all of the walls and towers surrounding the castle courtyard had disappeared; its building blocks were used for other buildings, only the foundations were visible.

20th and 21st centuries

Sir Arthur Churchman bought Orford Castle in 1928 and left the property to the Orford Town Trust in 1930 . Shortly afterwards, he called for donations to preserve and restore the castle. During the Second World War , the castle was fortified with barbed wire and was originally intended to be an anti-aircraft position; Nissen huts were set up around the keep . Instead, the castle was used as a radar display . In the southeastern tower extension, a concrete ceiling was put in place to carry the radar equipment. The Nissen huts were removed again after the end of the war.

Orford Castle became the Ministry of Works in 1962 and is now administered by English Heritage . The keep is the only part of the castle that is still intact today. The remains of the earth walls around the former courtyard are still visible, but not all of the trenches in them actually come from the Middle Ages, but result from earlier demolitions of the castle walls. The Orford Museum Trust has put together in the upper hall an exhibition of various archaeological artifacts that have been found in the area. Excavation work to understand the area around the Keep continued in 2002-2003. The castle is a Scheduled Monument and has been classified as a Grade I cultural monument by English Heritage .

The wild man of Orford

Orford Castle is linked to the legend of the Orford Wild Man. According to the chronicler Radulph von Coggeshall , around 1167 a naked, wild man, clad only in his own hair, was caught in the nets of local fishermen. The man was taken back to the castle, where he was detained for six months, during which time he was painfully questioned and tortured. He said nothing and behaved wildly. Eventually the wild man managed to escape from the castle. Later sources describe the captive as a merman (male mermaid ) and the incident appears to have fueled the appearance of "savage man" engravings on local baptismal fonts - about twenty such late medieval baptismal fonts exist in the coastal areas of Suffolk and Norfolk nearby from Orford.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Norman John Greville Pounds: The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a social and political history. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1994, ISBN 0-521-45828-5 , p. 55. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ A b R. Allen Brown: English Castles. Batsford, London 1962, OCLC 1392314 , p. 191. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ R. Allen Brown: English Castles. Batsford, London 1962, OCLC 1392314 , pp. 53, 191. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ Charles Henry Hartshorne: Observations on Orford Castle. In: Archaeologia. Issue 29 (1842), p. 60.

- ^ R. Allen Brown: English Castles. Batsford, London 1962. OCLC 1392314 , pp. 52-53. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ↑ TA Heslop: Orford Castle: nostalgia and sophisticated living. In: Robert Liddiard (ed.): Anglo-Norman Castles. Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2003, ISBN 0-85115-904-4 , pp. 279, 289. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ↑ TA Heslop: Orford Castle: nostalgia and sophisticated living. In: Robert Liddiard (ed.): Anglo-Norman Castles. Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2003, ISBN 0-85115-904-4 , p. 284. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ↑ TA Heslop: Orford Castle: nostalgia and sophisticated living. In: Robert Liddiard (ed.): Anglo-Norman Castles. Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2003, ISBN 0-85115-904-4 , pp. 283-284. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ↑ TA Heslop: Orford Castle: nostalgia and sophisticated living. In: Robert Liddiard (ed.): Anglo-Norman Castles. Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2003, ISBN 0-85115-904-4 , p. 293. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ↑ TA Heslop: Orford Castle: nostalgia and sophisticated living. In: Robert Liddiard (ed.): Anglo-Norman Castles. Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2003, ISBN 0-85115-904-4 , p. 279. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ↑ a b c Suffolk HER ORF 054. Heritage Gateway, accessed June 12, 2015.

- ^ R. Allen Brown: Allen Brown's English Castles. Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2004, ISBN 1-84383-069-8 , pp. 110-111. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ R. Allen Brown: Allen Brown's English Castles. Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2004, ISBN 1-84383-069-8 , p. 111. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ A b Robert Liddiard: Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Windgather Press, Macclesfield 2005, ISBN 0-9545575-2-2 , p. 47. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d Robert Liddiard: Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Windgather Press, Macclesfield 2005, ISBN 0-9545575-2-2 , p. 50. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ Robert Liddiard: Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Windgather Press, Macclesfield 2005, ISBN 0-9545575-2-2 , p. 49. Accessed June 12, 2015.

- ↑ TA Heslop: Orford Castle: nostalgia and sophisticated living. In: Robert Liddiard (ed.): Anglo-Norman Castles. Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2003, ISBN 0-85115-904-4 , pp. 288-289. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ↑ TA Heslop: Orford Castle: nostalgia and sophisticated living. In: Robert Liddiard (ed.): Anglo-Norman Castles. Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2003, ISBN 0-85115-904-4 , p. 290. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ R. Allen Brown: Allen Brown's English Castles. Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2004, ISBN 1-84383-069-8 , p. 136. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ A b Oliver Hamilton Creighton: Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England . Equinox, London 2005, ISBN 1-904768-67-9 , p. 44.

- ^ A b c d William White: History, Gazetteer and Directory of Suffolk . Robert Leader, Sheffield 1855. OCLC 21834184 , p. 517.

- ^ A b c William White: History, Gazetteer and Directory of Suffolk . Robert Leader, Sheffield 1855. OCLC 21834184 , p. 516.

- ↑ a b c d e Orford Castle. Historic England. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ A b Charles Henry Hartshorne: Observations on Orford Castle. In: Archaeologia. Issue 29, 1842, p. 61.

- ↑ a b Orford History. ( Memento of the original from May 28, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Orford and Gedgrave Parish Council. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ Montague Rhodes James: Suffolk and Norfolk: A Perambulation of the Two Counties. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2010, ISBN 978-1-108-01806-7 , p. 100. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ↑ a b Suffolk HER ORF 001. Heritage Gateway. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ The Museum. Orford Museum Trust. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ A b Paul Thompson: The English, the Trees, the Wild and the Green: two millennia of mythological metamorphoses. In: Stephen Hussey, Paul Thompson (eds.): Environmental Consciousness: the roots of a new political agenda. Transaction, New Brunswick 2004, ISBN 0-7658-0814-5 , p. 30. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ A b R. Varner: Gary Creatures in the Mist: Little People, Wild Men and Spirit Beings around the World. Algora 2007, ISBN 978-0-87586-546-1 , p. 78. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

Web links

Coordinates: 52 ° 5 ′ 39.3 " N , 1 ° 31 ′ 50.5" E