Postoperative nausea and vomiting

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| R11 | Nausea and vomiting |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

Postoperative nausea and vomiting are side effects of anesthesia procedures , especially general anesthesia ( general anesthesia), but also of regional anesthesia . The abbreviation PONV for the English postoperative nausea and vomiting is also often used in German-speaking countries .

The frequency of nausea and vomiting with general anesthesia without prophylactic measures is 20–30%. PONV is caused by various factors (influence of medication, personal disposition, external influences), the mechanism of development is not understood in detail.

Effective measures for therapy and prophylaxis are available with nausea-reducing drugs (anti- emetics ) and the modification of anesthesia procedures. A multimodal treatment concept can at least greatly reduce PONV.

Frequency and relevance

After an operation, the average frequency ( incidence ) of nausea and vomiting is 20–30%, making these the most important postoperative side effects alongside pain. With almost eight million anesthesia procedures performed, over two million patients are affected by this problem in Germany alone. The clinical significance of these side effects is high. Although PONV is usually self-limiting, in rare cases serious complications such as airway obstruction with consequent lack of oxygen , pneumothoraces , ruptures of the esophagus ( Boerhaave's syndrome ) and trachea and pronounced emphysema can arise. For the subjective well-being, avoiding postoperative nausea in patients is rated even more important than postoperative pain therapy. PONV also incurs considerable additional costs due to the necessary, unplanned inpatient treatment for outpatient interventions. A three-day anesthesia-related postoperative nausea can justify a compensation of 1000 €. In the case before the Koblenz Higher Regional Court , a patient at risk of PONV was given intravenous anesthesia to reduce nausea , but no additional preventive administration of an anti-emetic was administered .

Pathophysiology

Nausea and vomiting are vegetative protective reflexes that are supposed to protect the body from the absorption of toxic substances (toxins). Vomiting removes substances absorbed from the body through the gastrointestinal tract, which prevents further absorption by nausea. The associated feeling of illness leads as a learning effect to a future avoidance of the corresponding substances. When medication is administered via a vein (intravenous, parenteral) for therapeutic purposes, as happens in the context of chemotherapy (CINV, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting ) or general anesthesia , in which inhalation anesthetics and opioids are the main triggering (emetogenic) substances , these effects are undesirable.

Vomiting and nausea are not necessarily related phenomena. The vomiting center consists of core areas in the area of the brain stem . It receives incoming information ( afferents ) from the chemoreceptor trigger zone , in particular by means of the messenger substance dopamine (dopaminergic), the vagus nerve, here mainly by means of serotonin (serotoninergic) and from the vestibular organ, especially by histamine- mediated transmission (histaminergic). The complex vomiting reflex, in which the glottis finally relaxes , the lower esophageal sphincter relaxes and the abdominal muscles (abdominal pressure) and the diaphragm suddenly become tense , is mediated via core areas and nerve fibers ( efferents ) of the vegetative and motor nervous system. The nausea is caused by the action of substances on the chemoreceptor trigger zone at the floor of the fourth ventricle, but also requires the involvement of higher brain regions. In the area of the chemoreceptor trigger zone, the blood-brain barrier is permeable, so that foreign substances can pass from the blood into the brain.

While the increased release of serotonin plays the main role in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, the development of PONV is largely unclear in detail. In addition, it is not easily possible to transfer results from animal models to humans.

risk assessment

Risk factors

There are various clinically relevant risk factors for PONV that have been proven by good studies. Female gender is the most important patient-dependent factor. Women are at higher risk of nausea and vomiting postoperatively. A pathophysiological explanation for this is not known. PONV occurs twice as often in non-smokers as in smokers . This may be related to changes in dopamine receptors. PONV or motion sickness ( kinetoses ) that have already been experienced are further risk factors, which suggests an individual component in the development.

PONV occurs more frequently in children and adolescents between the ages of 6 and 16.

Anesthesia-dependent factors are the use of volatile anesthetics , the use of nitrous oxide during anesthesia and a long period of anesthesia, as well as the postoperative use of opioid pain relievers. In contrast, the choice of opioid has no significant influence. The antagonization of muscle relaxants with high doses of cholinesterase inhibitors such as neostigmine is also discussed as a risk factor. Short periods of anesthesia, the avoidance of inhalative anesthetics ( total intravenous anesthesia ) and regional anesthesia procedures lead to a reduced risk.

The data situation is not clear for a number of other factors. This concerns the type of operation, the experience of the anesthetist , the use of a nasogastric tube, and the presence of postoperative pain and movement stimuli. Influences from the body mass index , personality structures and a dependence on the menstrual cycle are refuted .

Risk assessment scores

Since the assessment of the risk of developing nausea and vomiting postoperatively on the basis of a single factor, such as gender, is not very precise ( sensitive ), different scores were developed for predictions. These should enable a differentiated prophylaxis. A simplified score (after Apfel ) or the score according to Koivuranta are known. The common apple score includes the four risk factors of female gender, non-smoking status, known motion sickness or previous postoperative nausea and the expected administration of opioid painkillers after the procedure. If there are 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 of these factors, the probability of PONV is around 10%, 20%, 40%, 60%, or 80%.

There are limitations to the use of such scores. The given probabilities are only to be used for adults; other scores, such as the POVOC, are used for children. Adequate predictions can only be made for about 70% of those affected. The overwhelming majority are also classified with a moderate risk, which does not provide any significant gain in knowledge for a practicable differentiation between risk patients and non-risk patients. However, the identification of risk factors can be used to identify patients who do not benefit from the administration of a prophylactic drug.

Treatment options

For the treatment and prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting, nausea-reducing agents (antiemetics) from various groups of agents, modifications of the anesthetic procedure and other supplementary measures are available.

Drugs (antiemetics)

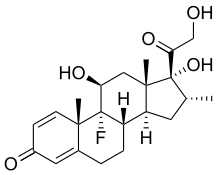

- Dexamethasone is a corticosteroid whose mechanism of action with regard to its antiemetic effect is not known. The effectiveness corresponds to that of other active ingredients, with dexamethasone being particularly suitable for combination with other antiemetics. Since the therapeutic effect only occurs after about two hours, it is often administered for prophylaxis early after induction of anesthesia if the risk profile is appropriate. Dexamethasone also has an analgesic, decongestant and mood-enhancing effect, which is generally desirable in the context of an operation. A negative influence on wound healing or the glucose balance could not be shown in the antiemetic dosage of 4 mg. There is currently no evidence that other corticosteroids are effective in PONV. During chemotherapy, dexamethasone is also used as an antiemetic (usually in combination with granisetron / ondansetron ).

- 5-HT 3 antagonists ("Setrons") are active ingredients that selectively block 5-HT 3 receptors (serotonin receptors). The substances used are granisetron , ondansetron , palonosetron and tropisetron , which are similarly suitable for prophylaxis and therapy in comparable doses. Occasionally, side effects are headache and constipation . Setrons can increase the QT time in the electrocardiogram ( QT syndrome ). For granisetron and tropisetron it has been shown as undesirable effects that they can neutralize the analgesic effect of paracetamol .

- The neuroleptic droperidol from the group of butyrophenones is effective at the dopamine receptor D2. A QT time prolongation could also be shown for droperidol (in five percent of patients), which is why production was suspended in 2001. The active ingredient has been approved again since 2008, as the necessary monitoring is regularly guaranteed in the context of performing anesthesia and subsequent recovery room care. Fatigue and extrapyramidal side effects can occur as further side effects , but these are only observed with high doses. Droperidol counteracts postoperative headaches. Haloperidol was used as a substitute for droperidol and is just as effective in reducing PONV, but the comparable side effects are more common, so its use is not justified.

- The antihistamine dimenhydrinate has an effect comparable to that of the other antiemetics. However, the rate of dose-related side effects, the optimal timing of administration, and the benefit of repeated doses are unclear.

- Metoclopramide from the group of benzamides acts on dopamine, serotonin and histamine receptors. The effectiveness of PONV is controversial. While metoclopramide is often classified as ineffective, other authors have seen its use as effective since the results of a multicenter study from 2006. Different dosages are primarily responsible for the differing evaluations. The most common side effect can be a short-lasting drop in blood pressure ( hypotension ). Fatigue is another rare side effect. Metoclopramide should not be given to children because of the occurrence of extrapyramidal disorders.

- Neurokinin antagonists (NK 1 antagonists) prevent the action of substance P on neurokinin receptors both in the vomiting center and on peripheral nerves. Since substances with an unselective effect on neurokinin receptors 1–3 are associated with cardiovascular side effects, the active substances used to treat nausea and vomiting are highly selective for the NK 1 receptor. Aprepitant is a representative that is only available for oral administration and is approved for the prophylaxis of PONV. Fosaprepitant , vofopitant , rolapitant and casopitant are active ingredients that can also be used intravenously, but are still in clinical testing. Aprepitant does not have a sedating effect; slight headaches and constipation are possible side effects. As a cytochrome P450 inhibitor, it can prolong the effectiveness of other drugs.

Modifications of the anesthetic procedures

If appropriate for the procedure, regional anesthesia procedures are available . They are associated with lower rates of postoperative nausea compared to general anesthesia. In procedures close to the spinal cord ( spinal anesthesia , epidural anesthesia ), PONV occurs in 10–15% of patients, in peripheral nerve blocks only in isolated cases. With regional anesthesia, the development of nausea and vomiting is usually due to a drop in blood pressure ( hypotension ) and is therefore treated with circulatory drugs and fluid therapy.

When performing general anesthesia, doing without inhalation anesthetics and instead performing total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) with propofol is an effective measure that reduces nausea and vomiting just as effectively as the administration of an anti-emetic. The decisive factor here is to avoid the substances that cause nausea, not to use propofol. A waiver of nitrous oxide has little effect.

Complementary measures

Acupressure (at point P6 on the wrist) was considered a possibility in a review. The treatment is attractive due to the very low rate of side effects. However, these were determined under study conditions; in perioperative practice, the implementation is limited both by concomitant diseases and the reduced consciousness of the patient, which can be associated with injuries, as well as by the expenditure of training and the time required for implementation. Acupuncture injections, electroacupuncture and acupressure procedures are mentioned as further treatment options, although insufficient data is available for a final assessment.

A meta-analysis showed that ginger is superior to placebo in reducing postoperative nausea; However, sufficiently large studies for a final assessment are not available. Abdominal pain can occur as a side effect.

literature

- D. Rüsch, LH Eberhart, J. Wallenborn, P. Ill people: Nausea and vomiting after operations under general anesthesia: an evidence-based overview of risk assessment, prophylaxis and therapy . In: Dtsch Arztebl Int. , 2010 Oct, 107 (42), pp. 733-741. PMID 21079721

- N. Roewer: Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting - A Problem of High Relevance. In: Anästhesiol Intensivmed Emergency Med Schmerzther. , 2009, 44, pp. 278-279. PMID 19367531

- L. Eberhart, P. Kranke: For whom is PÜ & E relevant - and who is a risk patient ? In: Anästhesiol Intensivmed Emergency Med Schmerzther. , 2009, 44, pp. 280-285. PMID 19367532

- L. Eberhart, P. Ill: Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting - How do I go about everyday life? Prophylaxis and therapy algorithms. In: Anästhesiol Intensivmed Emergency Med Schmerzther. , 2009, 44, pp. 286-295. PMID 19367533

- J. Wallenborn, L. Eberhart, P. Sick: Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting - Everything the same in the pharmacotherapy of PONV? In: Anästhesiol Intensivmed Emergency Med Schmerzther. , 2009, 44, pp. 296-305. PMID 19367534

- CC Apfel, P. Kranke, S. Piper and others: Nausea and vomiting in the postoperative phase. Expert and evidence-based recommendations on prophylaxis and therapy. In: Anaesthesist , 2007 Nov, 56 (11), pp. 1170-1180. Review. PMID 17726590

- CC Apfel, N. Roewer: Postoperative nausea and vomiting. In: Anaesthesist , 2004 Apr, 53 (4), pp. 377-389 Review. PMID 15190867

Individual evidence

- ↑ N. Roewer: Postoperative nausea and vomiting - a problem with high relevance. In: Anästhesiol Intensivmed Emergency Med Schmerzther. 2009; 44, pp. 278-279. PMID 19367531

- ↑ OLG Koblenz, judgment of June 20, 2012, file number 5 U 1450/11

- ↑ K. Jordan, C. Sippel, HJ Schmoll: Guidelines for antiemetic treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: past, present, and future recommendations . In: Oncologist , 2007 Sep; 12 (9), pp. 1143-1150. Review. PMID 17914084

- ↑ a b c d C. C. Apfel, N. Roewer: Postoperative nausea and vomiting. In: Anaesthesiologist. 2004 Apr; 53 (4), pp. 377-389 Review. PMID 15190867

- ^ BP Sweeney: Why does smoking protect against PONV? In: Br J Anaesth. 2002 Dec; 89 (6), pp. 810-813. Review. PMID 12453921

- ↑ Dirk Rüsch, Leopold HJ Eberhart, Jan Wallenborn, Peter Kranke: Nausea and vomiting after operations under general anesthesia: An evidence-based overview of risk assessment, prophylaxis and therapy. In: Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010; 107 (42), pp. 733-741; doi: 10.3238 / arztebl.2010.0733 .

- ↑ CC Apfel, CA Greim, C. Goepfert et al.: Postoperative vomiting. A score for predicting the risk of vomiting after inhalation anesthesia. In: Anaesthesiologist. 1998, 47, pp. 732-740, PMID 9799978 .

- ^ JR Sneyd, A. Carr, WD Byrom, AJ Bilski: A meta-analysis of nausea and vomiting following maintenance of anesthesia with propofol or inhalational agents. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: European journal of anaesthesiology. 1998; 15 (4), pp. 433-445.

- ↑ a b c L. Eberhart, P. Ill: For whom is PÜ & E relevant - and who is a risk patient ? In: Anästhesiol Intensivmed Emergency Med Schmerzther. 2009, 44, pp. 280-285. PMID 19367532

- ↑ CC Apfel, E. Läärä, M. Koivuranta, CA Greim, N. Roewer: A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. In: Anesthesiology. 1999 Sep; 91 (3), pp. 693-700. PMID 10485781

- ↑ M. Koivuranta, E. Läärä, L. Snåre, S. Alahuhta: A survey of postoperative nausea and vomiting. In: Anaesthesia. 1997 May, 52 (5), pp. 443-449. PMID 9165963

- ↑ LH Eberhart, AM Morin, M. Georgieff: Dexamethasone for the prophylaxis of nausea and vomiting in the postoperative phase - a meta-analysis of controlled randomized studies. In: Anaesthesiologist. 2000 Aug, 49 (8), pp. 713-720. PMID 11013774

- ↑ a b c d e J. Wallenborn, L. Eberhart, P. Ill: Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting - Everything the same in the pharmacotherapy of PONV? In: Anästhesiol Intensivmed Emergency Med Schmerzther. 2009; 44, pp. 296-305. PMID 19367534

- ↑ P. Kranke, AM Morin, N. Roewer, LH Eberhart: Dimenhydrinate for prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. In: Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002 Mar; 46 (3), pp. 238-244. PMID 11939912

- ^ J. Wallenborn, G. Gelbrich, D. Bulst et al.: Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting by metoclopramide combined with dexamethasone: randomized double blind multicentre trial . In: BMJ. , 2006 Aug 12, 333 (7563), p. 324. PMID 16861255 .

- ↑ L. Eberhart, P. Ill: Postoperative nausea and vomiting - How do I go about everyday life? Prophylaxis and therapy algorithms. In: Anästhesiol Intensivmed Emergency Med Schmerzther. 2009, 44, pp. 286-295. PMID 19367533

- ↑ A. Lee, LT Fan: Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. In: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15, (2), S. CD003281. PMID 19370583

- ^ DJ Rowbotham: Recent advances in the non-pharmacological management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. In: Br J Anaesth. 2005 Jul, 95 (1), pp. 77-81. Review. PMID 15805141

- ↑ N. Chaiyakunapruk, N. Kitikannakorn, S. Nathisuwan, K. Leeprakobboon, C. Leelasettagool: The efficacy of ginger for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis. In: Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jan, 194 (1), pp. 95-99. PMID 16389016

- ↑ B. White: Ginger: an overview. In: Am Fam Physician. 2007 Jun 1, 75 (11), pp. 1689-1691. Review. PMID 17575660