Pavel Alexandrovich Florensky

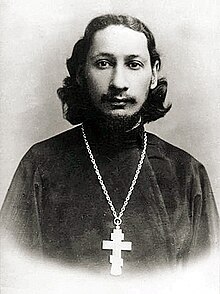

Pavel Florensky ( Russian Павел Александрович Флоренский , scientific. Transliteration Pavel Aleksandrovich Florensky * 9 . Jul / 21st January 1882 greg. Near Yevlakh , today Azerbaijan , † 8. December 1937 in Leningrad ) was a Russian religious philosopher , Theologian , mathematician and art scholar.

Life

Early years

Florensky was born on January 21, 1882 in the city of Yevlach in the Yelisavetpol Governorate of the Russian Empire (today West Azerbaijan ). His father came from a family of Russian Orthodox priests, his mother belonged to the Georgian - Armenian nobility.

After graduating from high school in Tbilisi , he went to the Department of Mathematics at Moscow University in 1900 and studied philosophy at the same time . In 1904 he graduated and refused to accept a chair at the university; instead he continued to study theology at the Moscow Spiritual Academy . Together with some fellow students he founded the Christian Fighting Union (Союз Христианской Борьбы) with the revolutionary goal of building a new Russian society based on the principles of Vladimir Solovyov . Shortly afterwards, in 1906, he was arrested for membership in this society; however, he had later lost interest in the radical Christian movement.

Intellectual interest

During his studies at the Spiritual Academy, Florenski was interested in philosophy, religion, art and folklore. He became a well-known exponent of Russian symbolism , made friends with Andrei Bely and published articles in the magazines Neuer Weg (Новый Путь) and Libra (Весы). He also began his most important philosophical work, The Pillar and the Foundations of Truth. An attempt on orthodox theodicy in twelve letters . The complete book was not published until 1924, but he was almost finished by 1908 after graduating from the academy.

In his great essay NAMEN Florenski gives a symbolic-psychological explanation of some names. With this book he proves himself to be one of the most important representatives of the Imjaslavie movement, which was concerned with the worship of God in his name . At the turn of the 20th century, this movement had dominated theological debate in Russian Orthodoxy . In his autobiography Florenski presents the core of his world view as follows: “But at that time I came up with the fundamental idea for my later world view, namely that what is named in the name, the symbolized in the symbol, the reality of what is represented is present in the representation and that hence the symbol is the symbolized. "

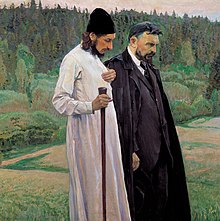

After studying at the academy, he taught philosophy there and lived in Sergiev Posad's Trinity Monastery until 1919 . In 1911 he was ordained a priest . In 1914 he wrote his dissertation on Spiritual Wisdom . He has published works on philosophy, theology, art history, mathematics and electromagnetism. Between 1911 and 1917 he was the editor-in-chief of one of the most authoritative Orthodox theological publications of the time, the Bogoslowski Westnik . He was also the spiritual teacher of the controversial Russian writer Vasily Rosanov and urged him to reconcile with the Orthodox Church.

Scientific work under communist rule

After the October Revolution , the Trinity Monastery was closed in 1918; the Church, where he was a priest, in 1921. He moved to Moscow and worked on the State Plan for the Electrification of Russia , on the recommendation of Leon Trotsky , who was deeply convinced that Florensky’s capabilities could help the government electrify rural Russia. According to contemporary witnesses, Florensky was a remarkable figure in his priest's gown alongside the other leading officials.

In 1924 he published a large monograph on dielectrics and his work The Pillar and the Foundations of Truth. An attempt on orthodox theodicy in twelve letters . At the same time, he worked as a scientific advisor to the Commission for the Protection of Art Monuments of the Trinity Sergei Monastery and published works on ancient Russian art.

In the second half of the 1920s he worked mainly in the fields of physics and electrodynamics; At the same time, his greatest scientific work, Imaginary Numbers in Geometry , was published, which dealt with the geometric interpretation of Albert Einstein's theory of relativity .

Exile, arrest and death

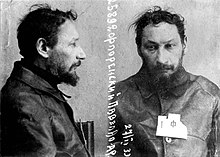

In 1928 Florensky was exiled to Nizhny Novgorod for three months . Due to the intercession of Yekaterina Pavlovna Peschkowa (first wife of Maxim Gorki ) he was allowed to return to Moscow. In 1933 he was arrested again and sentenced to ten years in a Gulag camp on the basis of Article 58 of the Criminal Code ( agitation against the Soviet system and counter-revolutionary propaganda , by which the monograph on the theory of relativity was meant).

He worked in the camp on the Baikal Amur highway until 1934, when he was transferred to the Solovetsky Islands to research the production of iodine and agar from local seaweed . In 1937 he was brought to Leningrad , where a troika sentenced him to death .

According to the documents in the Leningrad NKVD Archives Florensky was immediately after the meeting of the Troika on 8 December 1937 shot . According to research by the Russian human rights group Memorial in 2002, he was murdered with several hundred other prisoners sentenced to death. He was probably shot with the others on the Rzhev Polygon (an artillery firing range) near Toksovo, 20 kilometers south of Leningrad. Thousands of corpses were found there with the typical NKVD execution shot in the skull base on the neck. In 1958 Florensky was rehabilitated (sentenced to camp imprisonment, death sentence 1959).

Fonts

Works in ten deliveries:

- Pavel Florenskij: The Pillar and the Foundation of Truth. An attempt at an orthodox theodicy in twelve letters. Edition Context, Berlin (translation: Nikolai von Bubnoff) ( online, full text ).

- Pavel Florenskij: Christianity and Culture. Edition Context, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-931337-34-0 .

- Pavel Florenskij: Thought and Language. Edition Context, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-931337-16-2 .

- Pavel Florensky: names. Edition Context, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-931337-17-0 .

- Pavel Florenskij: Space and Time. Edition Context, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-931337-29-4 .

- Pavel Florenskij: On the watershed of thinking. A reader. 2nd edition, Edition Context, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-931337-05-7 .

- Appendix 1. Materials on Pavel Florenskij. Edition Context, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-931337-31-6 .

- Appendix 2. Materials on Pavel Florenskij. Edition Context, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-931337-35-9 .

literature

- Norbert Franz (Ed.): Pavel Florenskij - Tradition and Modernity. Contributions to the international symposium at the University of Potsdam, April 5 to 9, 2000. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-631-37537-9 .

- Luciano Fabro, Pavel Florenskij: VChUTEMAS. Reflections on the lectures «Space and Time in Fine Art», given by Pavel Florenskij in 1923 and 1924 at the VChUTEMAS in Moscow, given in 1995 at the Accademia di Brera in Milan. Gachnang & Springer, Bern / Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-906127-75-3 .

- Magdalena S. Gmehling: I saw the world as a whole. Pavel Florenkij - a master of polarities , in: Theologisches 45 (7–8 / 2015), Sp. 367–372.

- Avril Pyman : Pavel Florensky: A Quiet Genius The Tragic and Extraordinary Life of Russia's Unknown da Vinci. Continuum, New York / London 2010, ISBN 978-1-4411-8700-0 . ( Preview ).

- Loren Graham, Jean-Michel Kantor : Naming Infinity. A true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity , Cambridge, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009.

Web links

- Literature by and about Pawel Alexandrowitsch Florenski in the catalog of the German National Library

- Curriculum vitae on the GULAG website of Memorial Deutschland e. V.

- detailed illustrated biography of KONTEXTverlag

- Link catalog on the subject of Pawel Alexandrowitsch Florenski (Italian) at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Page about Florensky's stay on the Solovetsky Islands (Russian)

Individual evidence

- ^ Oleg Kolesnikow: Pawel Florensky. Retrieved May 3, 2009 (Russian).

- ↑ Pawel Florensky; Tatiana Shutowa: Pavel Florensky. Retrieved May 3, 2009 (Russian).

- ^ Sieglinde Mierau, Fritz Mierau (editor) and Pawel Florenski (author): names (works in ten deliveries, fourth delivery), Context Verlag, 2000.

- ↑ Tatjana Petzer et al. (Ed.): NAMEN - Designation - Adoration - Effect. Positions of European Modernism. Kulturverlag Kadmos, Berlin 2009. See in particular: Michael Hagemeister: Imjaslavie - Imjadejstvie. Name mysticism and name magic in Russia (1900-1930) , pp. 77-98; and Tatjana Petzer, Pavel and Aleksej, fools for Christ's sake. On the psychophysical effectiveness of names in Pavel A. Florenskij, pp. 121–142

- ^ Pavel Florensky: My children. Memories of a youth in the Caucasus. Translated by Fritz and Sieglinde Mierau. Urachhaus Verlag. Stuttgart 1993.

- ^ A b Graham, Kantor, Naming Infinity, Harvard UP 2009, p. 145

- ^ Antonio Maccioni: Pavel Aleksandrovič Florenskij. Note in margine all'ultima ricezione italiana. (PDF; 151 kB) In: eSamizdat, 2007, V (1–2). Pp. 471–478 , accessed May 3, 2009 (Italian).

- ^ Gulag Memorial , entry Florensky

- ^ Dennis Lomas, MAA Review , 2010

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Florensky, Pavel Alexandrovich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Павел Александрович Флоренский (Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian religious philosopher, theologian, mathematician and art scholar |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 21, 1882 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | near Jewlach , today Azerbaijan |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 8, 1937 |

| Place of death | Leningrad Oblast |