Anderitum Castle

| Pevensey Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Anderitum , b) Anderida , c) Anteridos , d) Anderelio |

| limes | Britain |

| section | Litus saxonicum |

| Dating (occupancy) | 3rd to 5th century AD |

| Type |

a) Fleet fort b) Limitanei fort |

| unit |

a) Classis Britannica ?, b) Numerus Abulcorum |

| size | approx. 3.65 ha |

| Construction | Stone construction, irregular, oval layout |

| State of preservation | Fort integrated into the Norman castle complex, south side badly damaged or completely disappeared, rising masonry of the north and west wall partially preserved up to 5 m high, north wall overturned in sections |

| place | Pevensey |

| Geographical location | 50 ° 49 '9 " N , 0 ° 19' 59" E |

| Previous | Fort Lemanis (Lymphne) east |

| Subsequently | Portus Adurni (Portchester) west |

| Differences at the time of the Norman invasion (1066) |

|---|

| Alan Ernest Sorrell , around 1960 |

| Flickr

Link to the picture |

Anderitum was a Limitanei fort and naval base of the Classis Britannica on the Limes of the British " Saxon Coast ", the remains of which have been preserved around the Pevensey Castle near today's Pevensey in East Sussex County , England .

Anderitum is the largest of the Saxon coastal fort in terms of area. Its occupation was supposed to prevent raids or attempts at immigration by the Saxons, Jutes and Angles. After the end of Roman rule over Britain in the early 5th century, it became a temporary refuge for Roman civilians until it was stormed by the Saxons in AD 491. The fort was the site of the landing of Norman Duke William the Conqueror in 1066 , who later had a castle built inside the Roman fortress . Elizabeth I used the fort as a weapon place to defend against the Spanish Armada . During the Second World War, bunkers were built into the Norman ruins in preparation to ward off a German invasion.

Surname

The fort is mentioned in the Notitia Dignitatum as Anderidos , it appears between the entries for Rutupiae (Richborough, Kent) and Portus Adurni (Portchester, Hampshire), and is mentioned for the last time by the geographer of Ravenna around 700, there under the name Anderelio , next to Iacio Dulma (Towcester, Northamptonshire) and Mutuantonis , a station in south-east England that has not yet been located. The Anglo-Saxons called the site Andredes ceaster or Andred . Probably a personal name similar to Ēanrēd. The forest that stretched about 200 kilometers from here to Dorset was known as Andredsweald , and from there it reached the coast. Later this place was also known as Caer Ponsavelcoit (near Nennius ) or Pefele (Pefe's island). In the 6th century the area was also known as Desertum Ondred (the wasteland of Ondred).

location

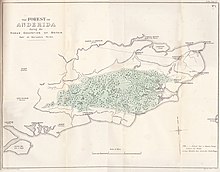

The fort is located on a small peninsula above the coastal marshes, from which one can overlook the flat landscape around Pevensey. In ancient times, the location of the fort was surrounded on three sides by water or salt marshes that reached as far as Hailsham . Only in the west was it connected to the mainland by a narrow land bridge. At high tide, a few dry places protrude from the marshes, which are now called Rickney, Horse Eye, North Eye and Pevensey - place names that end in -eye meant “island” in Old English . Today the ruin stands about a kilometer inland.

function

The fort protected a large anchoring bay extending to the northeast. Apart from fragments of some brick stamps of the Classis Britannica from the 2nd or 3rd century, which suggest a previous operation as a naval station or protected anchorage, the military use of the area probably only began after the usurpation of Carausius . The aim was to close the gap in the fortress chain between Portus Adurni (Portchester) and Portus Lemanis (Lympne). After the dissolution of the Roman military and civil administration in Britain, the fort was used as a fortified civil settlement ( oppidum ) .

Road links

Between 1929 and 1949 the course of a Roman road was investigated, which ran from the fort to the west. It began at the west gate and led from there to the south-west to a cemetery in front of a depression in which the port of the fort was suspected. The road subsequently led north-west, crossed today's Pevensey-Eastbourne (B2191) and then followed the course of Peelings Lane to Stone-Cross, from where it turned west towards Polegate.

Research history

The first observations were made in 1710 when it was discovered during the construction of an aqueduct for Pevensey that the fort walls stood on perfectly preserved pilots . The first scientific excavations were started between 1853 and 1858 by Mark Anthony Lower and Charles Roach Smith at the west gate. During these excavations mainly broken roof tiles of the gate building, an amulet, a coin from the time of Constantine I and two fragments of columns came to light. It was also discovered that the interior of the fort had been filled with clay for leveling, so that the ground level here was significantly higher than outside the fort walls. The east gate was then examined. In the NW and NE, a number of search trenches were also dug in order to gain more clarity about the nature of the interior development. Here, however, mainly ceramics, coins and broken roof tiles came to the fore, no building remains could be discovered. Finally, the collapsed or completely disappeared sections of the fence in the north and south were examined. The southern sections had either been torn down when the Norman fortress was built, or destroyed by landslides; the reasons that led to the loss of the northern parts of the wall could not be clarified. The remains of two smaller exit ports were found on the north and south sides.

The late Roman fort was first examined in more detail by Louis F. Salzmann, who directed the excavations from 1906 to 1908. In 1906, Salzmann took a closer look at the construction of the fort walls. He subsequently also examined the area around the fort gates, measuring u. a. the passage of the east gate and determined the structural features of the northern exit gate. In the north sector of the fort, in the area of the overturned wall sections, some search trenches were dug. The finds contained a total of two bricks with the stamp of the British fleet (CL-BR), but these could also have been used a second time and originally come from a Roman villa in nearby Eastbourne. In addition to a small number of human skulls, animal bones of ox, sheep, geese, horses, boars, dogs, cats, some species of birds and fish came to light during the excavations. Other exploratory excavations carried out by Salzmann that year did not yield any further new findings; only a few remains of the wall were found that may have been connected with the development of the fort. Only Roman ceramics and coins from the 3rd and late 4th centuries AD came to light more often.

Between 1936 and 1939 the archaeologists Frank Cottrill (1936), Burgess (1937) and B. W. Pearce (1938–1939) explored the fort. Cottrill dug u. a. at the east gate a Roman road from the 4th century AD that had been renewed twice. The medieval paving was also recognizable above the ancient street. The street was flanked by remains of buildings and garbage pits from Anglo-Saxon-Norman times. Cottrill also examined the area at the west gate, since the first excavations by Roach-Smith had only been carried out very superficially there. The findings were not published. Malcolm Lyne evaluated the excavation results in 1990 and published his report for the first time in the journal of the Sussex Archaeological Society Library.

development

Pevensey often played a prominent role due to its location in English history. The history of this place is also closely linked to its Norman castle, Pevensey Castle , which incorporated the fort's fortifications.

In the second half of the 3rd century, Germanic pirates from the continent began raiding the Roman maritime trade between the coasts of northern Gaul and southeastern Britain. From 270 onwards, the Classis Britannica could no longer keep the pirates at bay on its own. To repel them, among other things, the fleet was enlarged, at the same time the Romans built a chain of massive stone forts on the British coast, in which the new naval departments were stationed, around strategically important estuaries or natural harbors - like that of Pevensey - against such raids better protect. When, after the Romans withdrew in 410, the pressure of the Anglo-Saxons on Britain's coasts increased and they slowly began to take over the fertile Lowlands as well, some Romano-British took refuge in the forts on the Saxon coast, most of which were probably still intact. However, this only temporarily protected them from the invaders. Anderitum was besieged and stormed in 491 by the Anglo-Saxons under the command of the first King of Sussex Ælle (477 to 514) and his son Cissa . This is one of the rare surviving reports from the Migration Period about the successful siege of a strongly fortified Roman settlement by the new immigrants. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports the unsuccessful attempt to defend the walls against the attack of the Saxons and the massacre of its inhabitants after they entered the fortress:

" The Anglo-Saxons under their chiefs Ælle and Cissa besieged Andredes ceaster and slaughtered everyone they met here, so that none of the British survived "

The Romano-British were apparently no longer safe even in heavily fortified settlements. The decisive reason for their demise was probably that they had built a wide dam over the otherwise difficult to pass moat that separated the western gate from the surrounding area in the early 5th century and then possibly could not remove it in time. This now made it easier to access the main gate of the fort and thus made it even more difficult to defend the wall, also because the defenders were probably not numerous enough to occupy all the endangered points. It is uncertain whether the fortress was reoccupied after this tragic event. From the middle of the 6th century the fort was probably inhabited by Saxon settlers. These left behind pottery, glass and other objects that were recovered during the excavations. In the late Anglo-Saxon period, Pevensey established itself as a fishing port and salt producer.

In 1042, the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson had the ruins of the fort fortified again, among other things, trenches were dug within the Roman wall. In 1066 the garrison was withdrawn again and marched against the Norwegians under King Harald Hardraada , who had meanwhile invaded the north, so that William the Conqueror could land there unhindered with his army in September of the same year. After the Norman invasion, the fortress was handed over to William's half-brother, Robert de Mortain, who founded a small settlement outside the Roman walls and built new fortifications into the ruins of the castle. A third of the fort area was separated by a palisade wall and the ruined Roman walls in this part were repaired. At the same time or only a little later a defense tower ( Motte ) was also built. In 1088 the Norman castle was besieged by Wilhelm Rufus , again during the civil war for the successor to Heinrich I (1135-1154), and a third time in 1264 by Simon V. de Montfort . Queen Elizabeth I ordered the razing of the castle, but the order was revoked and it continued to be used as an arsenal. Under Oliver Cromwell another attempt was made - unsuccessfully - to destroy it. In 1942, in view of an expected German invasion, the British Home Guard set up anti-aircraft and observation posts as well as a radio station.

Fort

Due to the unusual shape of the fortifications, it was long assumed that the fortification was built around 340. After finding coins and examining and dating wood samples from the foundations of the wall, the construction was almost certainly commissioned around the year 293 under the rule of the usurper Allectus . With an area of approx. 3.65 hectares, it is one of the largest such structures on the Litus Saxonicum . The oval shape of the floor plan adapts exactly to the contours of the peninsula at that time. Almost two thirds of the total 760 meter long wall has survived relatively well over the centuries. The south-east corner was later built over by the Norman weir system. A landslide destroyed an approximately 180 meter long section of the SE wall. Of the overturned fragments of the masonry, most have been removed over the years.

It is estimated that between 115 and 285 men over a period of max. five years were used in the construction of the fort. They are likely to have been organized in at least four work units. Each team had to complete a section of wall about 20 meters. This could be recognized by the exactly vertical breaks in the individual - in some cases already overturned - segments. They also differ in the number of rows of bricks and flint stones. This could mean that certain types of material were not always available in sufficient quantities during the construction work. The amount of building material required for the fort was very large; it is estimated that around 31,600 cubic meters of stone and mortar were used. It is not known how it was transported to the construction site, but that amount of material could have filled about 600 boat loads or 49,000 truckloads. That would be around 250 wagons pulled by 1,500–2,000 oxen. Given such an immense amount of land transport, it seems more likely that it was brought by sea instead. But this was undoubtedly a logistical challenge for the Roman canal fleet as well. It is estimated that 18 ships were used over a period of 280 days.

Enclosure

The fortifications represent a further stage in the development of late Roman military architecture. The 4.6 meter deep foundations in particular were laid very carefully and with great expertise. Wooden pilots made of oak wood were driven vertically into the bottom of the foundation trench and a layer of flint, clay and crushed limestone was first applied one after the other and pounded into place. Two wooden plank gratings were placed on top of this, the spaces between them being filled with limestone blocks and then additionally poured over with mortar to protect the foundation against the seepage of water. The result was an extremely stable, but still sufficiently flexible platform that was able to support a solid wall that was new at the time, a free-standing cast mortar construction with sandstone facing without an earth ramp that was piled up at the back and reached the battlements. Nevertheless, an earth ramp - albeit only very low - could also be detected in Pevensey. Some of the walls still tower over 8 meters today; 3.7-4.2 meters thick at the base, they taper in steps to the top of the wall to about 2.4 meters. The battlements were covered with tiles. The outer wall cladding is interrupted at the bottom by two horizontally running sandstone slabs and further up by two tile strips, which better connect the green sandstone facing with the cast mortar core ( brick penetration ). The latter mainly consists of mortared flint quarries. A big problem is the sometimes dense vegetation that has settled around the ruin over the years. In some places the roots have already penetrated deep into the masonry and could cause irreversible damage. As with many ancient monuments, repairs have been made to the fort wall over the centuries, with some of these restoration attempts being particularly ambitious. The Office of Works carried out a number of stabilization measures on the top of the wall in the 1920s, using high-cement mortar, which was considered the best solution at the time. However, this mortar was responsible for the increased degradation of the adjacent material, which is bound by softer lime mortar. Recently, hot lime mortar mixes have been tested to see how they react to the salty sea air.

Gates and towers

A total of three gates could be determined: the strongly fortified west gate, the east gate and a small passage on the north wall. The existence of another gate in the poorly preserved southern wall is likely. The west gate is a further developed form of the "Watergate" in the neighboring fort Portus Adurni (Portchester). It consisted of a central, two-story gatehouse with a vaulted chamber, of which only the foundations have been preserved, the semicircular vaulted passage itself measures approx. 2.75 m. The gateway located behind the Wallinie is also flanked by two two-storey, tile-roofed U-towers standing on massive cast wall bases, which were about eight meters apart. This type of construction allowed the defenders to open fire on attackers who had advanced to the gate simultaneously from three positions. Like the rest of the wall construction, the gate was built from sandstone blocks that were reinforced with vertical brick and sandstone slabs. Here, too, the core consisted mainly of flint stone. The gate on the east side of the fortress was just very simple. Originally an archway about 3 meters wide spanned the entrance. From here one could get to the Roman port, which is now overlaid by the modern Pevensey. The preserved archway dates from Norman times. During the excavations, traces of a wooden bridge could still be found in front of the gate. The 2 meter wide hatch on the north-western outer wall is no longer preserved.

The wall was originally reinforced by fifteen cantilevered, semicircular towers (diameter about 5 meters) with massive cast wall bases and a square tower, which were added at irregular intervals and concentrated on the ends of the western and eastern wall section. Ten of these towers have been preserved to this day.

Trenches

Outside the west gate, Cottrill observed the traces of Roman and medieval (V-shaped) moats that ran from north to south. The Roman specimens, around 5.5 meters wide, surrounded the fort on three sides, and the sea protected the camp in the south. In Norman times, only the gate areas were surrounded by ditches. Since they were not interrupted in front of the gates, it is assumed that they were once spanned by wooden bridges.

Interior development

Only minor traces of the interior development could be observed. According to the excavators, it probably only consisted of easily perishable material. In 1906 Louis Salzmann was able to confirm through his excavations that the interior development during the Romano-British period consisted mainly of very simple wooden buildings with walls made of wattle and daub. A crew of up to 1,000 men, along with their cattle and supplies, could be accommodated in the buildings. Some were heated with brick stoves. Some of the bricks were stamped with the Classis Britannica .

garrison

| Time position | Troop name | comment |

| 4th to 5th Century AD | Numeri Abulcorum | In the Notitia Dignitatum a praepositus is given for the late antique Anderidos , as the commander of an abulci unit. In earlier times, a Praepositus was still in command of a vexillation . The Abulci themselves originally came from Abula in the province of Tarraconensis , which u. a. is mentioned in the Geographica of Claudius Ptolemy . Today this city is known under the name Avila in the central highlands of Spain. This unit could also have been members of a Germanic tribe. Abulci are also mentioned as a unit of the field army ( comitatenses ) in Gaul and in a campaign to suppress the rebellion of Magnentius in the Pannonia Secunda province in 351. Possibly they were federates , warriors who were recruited from allied barbarian tribes and ideally placed under the command of a Roman officer. But it could also have been a largely autonomous force. According to the Notitia, associations of this type were also stationed in other forts on the Saxon coast. The occupation of the Anderitum belonged to the border troops ( Limitanei ) of the Comes litoris Saxonici per Britanniam . It is believed that military activity there continued uninterrupted into the 5th century. In its final phase, the number consisted for the most part of Germanic immigrants. Since this outpost was probably no longer supplied by state magazines at that time, they and their families mostly ran small, tax-exempt farms and produced everything they needed to live on site. |

| 4th century AD? |

Classis Britannica (the British fleet) |

Whether there were units of the canal fleet in the port of the fort has not been recorded by contemporary sources, but it is very likely due to the location of the fort. |

Inscriptions

No Roman inscriptions are known from Pevensey, but some brick stamps have been found in the fort. These are brick fragments with the inscription CL BR (Classis Britannica) from the 2nd or 3rd century.

In 1902, the amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson discovered bricks with the stamp HON [orius] AVG [ustus] ANDRIA ("Honorius Augustus , from Andria") in Pevensey Castle and saw them as a sign of renovation measures in the reign of Honorius (395-423). However, later scientific investigations proved that these bricks are all modern forgeries.

literature

- Arthur Hussey: An Inquiry after the Site of Anderida or Andredesceaster . Sussex Archaeological Collections , 6, 1853.

- Mark Anthony Lower: On Pevensey Castle and the Recent Excavations there . Sussex Archaeological Collections , 6, 1853.

- Charles Roach Smith: Excavations Made Upon the Site of the Roman Castrum at Pevensey . Privately Printed, 1858.

- Mark Anthony Lower: Chronicles of Pevensey , J. Richards, 1873.

- Louis F. Salzmann: Documents Relating to Pevensey Castle , Sussex Archaeological Collections , 49, 1906.

- Louis F. Salzmann: Excavations on the site of the Roman Fortress at Pevensey , 1907-1908, Arch. J. 65 (2) 1908b.

- Louis F. Salzmann: Excavations at Pevensey , 1907-1908, Sussex Archaeological Collections , 52, 1909.

- Louis F. Salzmann: Victoria County History of Sussex , Volume III, University of London, 1935.

- Louis F. Salzman: Excavations at Pevensey, 1906-7. In: Sussex Archaeological Collections 51, 1908, pp. 99-114.

- Louis F. Salzman: Excavations at Pevensey, 1907-8. In: Sussex Archaeological Collections 52, 1909, pp. 83-95.

- Ivan Donald Margary: Roman Roads from Pevensey. In: Sussex Archaeological Collections , 80, 1929.

- Joscelyn Plunket Bushe-Fox: Some Notes on Roman Coastal Defenses. In: The Journal of Roman Studies 22, 1932, pp. 60-72.

- Robin George Collingwood : The Archeology of Roman Britain . Methuen, London 1930.

- Ivan Donald Margary: Roman Ways in the Weald . Phoenix House, 1949.

- Stephen Johnson: The Roman Forts of the Saxon Shore. Elec. 1976, ISBN 023640024X .

- Peter Salway: Roman Britain . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1981.

- Charles Peers: Pevensey Castle . English Heritage, London 1985.

- Stephen Johnson: "Pevensey". In: Valerie A. Maxfield, The Saxon Shore: A Handbook. University of Exeter, 1989. ISBN 0-85989-330-8 .

- Michael G. Fulford: Excavations at Pevensey Castle . Interim Report, 1993.

- Simon Mc Dowall, Gerry Embleton: Late Roman Infantryman, 236-565 AD. Weapons - Armor - Tactics . Osprey Military, Oxford 1994, ISBN 1-85532-419-9 (Warrior Series 9).

- Andrew Pearson: Building Anderita. Late Roman coastal defenses and the construction of the Saxon shore fort at Pevensey. In: Oxford Journal of Archeology 18, 1999, pp. 95-117.

- Andrew Pearson: The Roman Shore Forts. Coastal Defenses of Southern Britain. Tempus, Stroud 2002.

- Roger JA Wilson: A Guide to the Roman Remains in Britain. 4th edition. Constable, London 2002.

- David JP Mason: Roman Britain and the Roman Navy . Tempus, Stroud 2003.

- Nic Fields: Rome's Saxon Shore Coastal Defenses of Roman Britain AD 250-500 . Osprey Books, Oxford 2006 (Fortress 56).

- Malcolm Lyne: Excavations at Pevensey Castle 1936 to 1964 . British Archaeological Reports, British series. 503. Archeopress, Oxford 2009, ISBN 978-1-4073-0629-2 .

- John Goodall: Pevensey Castle. English Heritage, 2013. ISBN 978-1-85074-722-2 .

Web links

- Pevensey Castle at Sussex Archeology

- Pevensey Castle - the Roman Fort of Anderita

- Pevensey Castle at Historic England

- Aerial view of the fort area (English Heritage)

- Differences in Castles | Forts | Battles

Remarks

- ^ Geographer of Ravenna 68.

- ^ Margary: 1929, p. 29; 1949, p. 186.

- ^ Lower: 1853, p. 267.

- ↑ Louis Salzmann: 1908a p. 102

- ↑ Louis Salzmann: 1908a, p. 106

- ↑ Malcolm Lyne: 1990, p. 26.

- ↑ Malcolm Lyne: 1990, p. 43.

- ↑ Malcolm Lyne 2009, p. 1.

- ↑ A. Pearson 2003, pp. 94-95.

- ↑ Nic Fields: 2006, p. 23, R. J. Collingwood: 1930, p. 53, J. Goodall 2013, p. 16, Johnson 1976, pp. 144-145.

- ↑ Malcolm Lyne: 1990, p. 43.

- ^ ND Occ .: XXVIII, 11, Praepositus numeri Abulcorum, Anderidos .

- ↑ Notitia Dignitatum XXVII, 20, McDowall, Embleton: 1994, p. 64, Stephen Johnson 1976, p. 70 and 1989, pp. 157-160.

- ↑ Gerald Brodribb: Stamped tiles of the 'Classis Britannica'. In: Sussex Archaeological Collection 107, 1969, pp. 102-127.

- ^ Charles Dawson: Note on some inscribed bricks and tiles from the Roman Castra at Pevensey (Anderida?), Sussex. In: Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries 21, 1907, pp. 410-413 full text .

- ^ David Peacock: Forged Brick-Stamps from Pevensey. In: Antiquity 47, 1973, pp. 138-140 full text ; Mark Jones (Ed.): Fake? The Art of Deception. British Museum Publications, London 1990, ISBN 0-7141-1703-X , p. 96, No. 91 Google Books ; British Museum database .