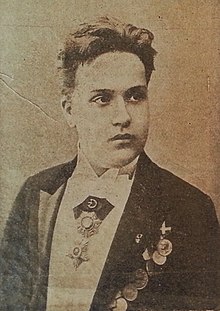

Raoul Koczalski

Raoul Armand Georg von Koczala Koczalski (spelling of the first name in Poland mostly: Raul, pronunciation: [kɔˈt͡ʃalski], simplified transcription: [kotschálski]; * January 3, 1885 in Warsaw , † November 24, 1948 in Posen ; pseudonym: Jerzy Armando and Georg Armand (o) ) was a Polish pianist and composer .

Life

Koczalski was born in Warsaw , which was then part of the Russian Empire. The music-loving family comes from an old Polish noble family. After initial instruction from the mother, the child becomes a student of Julian Gadomski (harmony and piano), Ludwig Marek (piano), Henryk Jarecki (composition and instrumentation) and the Chopin student Karol Mikuli (piano and composition), who was artistic director until 1888 at the Conservatory in Lemberg , (Polish Lwów, today Ukrainian Lwiw) was. The daily two-hour lessons with Mikuli extend from 1892 over four years in the summer months. The gifted boy's education is only on a private basis, he does not attend a conservatory. The three-year-old child appeared in public for the first time on March 15, 1888 in Warsaw as part of a charity event and then traveled to Europe as a child prodigy . The boy is showered with prizes and honors. The Spanish king, the Turkish sultan and the Persian Shah appoint him court pianist. From 1897 the Koczalski family has been based in Bad Ems , from where the concert tours begin. The proceeds of the concerts organized by the father are also used to finance the lifestyle of the whole family, which is described as lavish, and accompanies the child on his travels. The 1000th concert takes place in 1897. By today's standards, this must be termed child exploitation. In addition to his concert activities, Koczalski has been composing since early childhood. In the period before the outbreak of World War I , he temporarily lived in Paris , but plans to make Berlin the focus of his activities, a project that he did not realize until much later (1934).

The First World War interrupts his concert activities. At the end of July 1914 he returned to Germany from a concert tour from St. Petersburg. He was surprised by the outbreak of the First World War, arrested as a Russian citizen and interned with his family in Bad Nauheim in Hesse until 1918. He was banned from performing and devoted himself primarily to composing. The concerts after the war are not as successful as before. In his autobiographical considerations , Koczalski writes that hard strokes of fate, especially the death of his beloved mother, temporarily alienated him from music. He gives piano lessons and works as a critic under a pseudonym.

After the end of the war in 1918, Koczalski settled in Wiesbaden , and in 1926 he moved to Stresa on Lake Maggiore in northern Italy . He composes, teaches and occasionally gives concerts. The music school he founded goes bankrupt. He spent the winter months in Paris , where he attended lectures on musicology and philosophy at the Sorbonne until 1934 and organized music evenings during which he gave lectures with demonstrations at the piano.

It was only in 1934, after he moved to Berlin , that his international concert activities began again in full. Koczalski makes numerous records (especially for the Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft ). After the outbreak of World War II on September 14, 1939 , he was appointed to the Reich Chancellery to join Goebbels , who knew and admired Koczalski personally from his concerts. Goebbels hypocritically advises him to stop public appearances and not to leave Berlin for security reasons and because of the expected demonstrations against concerts by a Polish artist, which amounts to internment until the end of the war in 1945. His bank accounts are blocked and his records are taken from the market. However, he gives house concerts for students and friends and gives lessons. Although he has to report to the police regularly, in contrast to his compatriots exposed to Nazi terror, he seems to enjoy a certain protection. For example, together with the actor Paul Hartmann , he was asked to perform as a reciter on March 16, 1944, before officers of the Wehrmacht . After the war, Koczalski is suspected of collaborating with the Nazi regime in Poland. According to today's Polish view, the accusations are unfounded.

A short time after the end of the Second World War, in June 1945, Koczalski resumed his concert activities under sometimes adventurous circumstances in bombed-out Berlin. He left Germany soon afterwards and after a decade-long absence returned to Poland in July 1946, which Polish opponents interpreted as opportunism. He settled in Poznan and became a piano professor at the State Music Academy there, and later (from September 1, 1948)) in Warsaw. He will keep his Berlin residence at Königsallee 1 (today: Halenseestraße 1).

The last lifetime is overshadowed by illness. He has diabetes and pancreatic cancer. Although Koczalski is aware of his condition, numerous concerts are planned for 1948, and especially for the Chopin commemorative year 1949. Shortly before a performance at a concert on November 23, 1948 at the Music Academy in Poznan, where he and a student a. a. Chopin's Rondo for two pianos in C major, Koczalski loses consciousness. He suffers a heart attack and dies a day later, on November 24th, in hospital.

Koczalski's final resting place, after being reburied from the Jężycki Posen Cemetery in 1959, is in the Cmentarz Zasłużonych Wielkopolan (Cemetery of the Honored Inhabitants of Greater Poland ) in Poznan.

The State Council of the People's Republic of Poland (Rada państwa Polskiej Rzeczypospolitej Ludowej), chaired by the President of the People's Republic of Poland, Bolesław Bierut , posthumously awards the “Citizen Prof. Koczalski Raul the Cross of a Commander of the Order of the Polish Rebirth” ( Polonia Restituta) on November 27, 1948 , Order Odrodzenia Polski).

Parts of the scattered estate of Koczalski are in the library of the State Institute for Music Research in Berlin and in the music department of the State Library in Berlin .

Act

The pianist

Koczalski became famous primarily as an interpreter of the works of Frédéric Chopin . His repertoire also included works by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven (all the piano sonatas he played as a cycle), Schubert, Schumann, Liszt, A. Rubinstein, Paderewski, Bartok, as well as his own compositions. His playing is very well documented through numerous recordings - piano rolls, records and radio recordings. Koczalski laid out the principles of his Chopin interpretations in writings that were originally intended as introductions to his Chopin Evenings. In terms of understanding Chopin's music, they are just as important as the information provided by Bronisław von Poźniak , the other representative of the Polish Chopin tradition of the Lviv School. Koczalski's edition of Chopin's piano works, which was contractually planned for the Breitkopf & Härtel publishing house in 1947, has unfortunately never been published. The recordings, especially the recordings and radio recordings, are now available on CD; many recordings, including those on piano rolls, are available online.

Koczalski's piano playing is characterized by great ease and fluidity. Hence his preference for the grand pianos from the Leipzig company Julius Blüthner , famous for their easy playing and warm sound , which they made available to him on his concert tours. Leggiero and legato, often prescribed by Chopin, sometimes even at the same time, are frequently used types of articulation with a clear preference for the lower and middle range of the dynamic range. Thundering virtuoso playing was not his thing. Even in the études, which are so often misused as technical bravura pieces, Koczalski puts the poetic and sonic magic in the foreground, without, however, missing the necessary virtuosity. As Chopin's grandchildren, Koczalski, like the Polish master, pays homage to the ideal of bel canto , the realization of which was an important characteristic of Koczalski's playing style. Good examples of this are his recordings of the Nocturnes or the Berceuse op. 57, the figurative work of which tempts you to play mechanically and technically, but is to a certain extent dematerialized by Koczalski. Here, too, the floating lightness is reminiscent of Chopin's work instructions that he gave his students in class: “facilement”. In comparison with the great Chopin players of today, however, mannerisms and technical volatility, just as with his great, valued Western antipode Alfred Cortot, are striking , which sometimes raise doubts as to whether these two well-known representatives of the older generation of Chopin players actually, as often claimed will play the authentic Chopin. In his writings, however, Koczalski advocates a calm, simple and modest game without “virtuoso antics”, without “pathological sentimentality in the treatment of the cantilena”. In the treatment of rhythm and agogic, he turns against all exaggerations, in spite of certain freedoms, the necessity of which he admits. The peculiarities that we sometimes hear in Koczalski's recordings, which we perceive as mannerisms today, e.g. B. striking the left hand in front of the right, arpeggating chords, excessive rubato, tempo fluctuations, etc., were part of the interpretation style of most pianists of the older generation, which has its roots in the 19th century (sometimes even earlier) than the instrumentalists still mastered the art of improvisation : over an accompaniment of the left hand, a freely designed melody unfolds that does not always run synchronously with the accompaniment. This practice is therefore musically justified and not always a negligence on the part of the performer. In jazz recordings, e.g. B. with Louis Armstrong , but also with chansons, z. B. This practice can be observed in Marlene Dietrich's presentation .

Koczalski's play has received varying assessments. Most of them were positive. But there was also no lack of criticism. Even as a child prodigy, Koczalski felt a negative attitude from the music critics in his hometown of Warsaw, which particularly offended the young pianist, who was otherwise overwhelmed with praise. The Warsaw reviews of concerts by the adult pianist were also always much more reserved than the enthusiastic reviews abroad, especially in Germany. Peculiarities of his game, which were criticized as old-fashioned in Poland, were praised in Germany. But not of all. Is known Claudio Arrau's verdict: "In Germany was a man named Koczalski idolized. He only played Chopin. It was miserable. ” Arthur Rubinstein's judgment in his memoirs is also negative, although more subjective reasons may have played a role for the obvious maliciousness of his criticism. The great esteem that Koczalski enjoyed abroad, also from an economic point of view, was the reason why he stayed away from his native Poland for so long. He once said that he would have almost 300 listeners at a concert in Warsaw, while in Hamburg a hall that could hold 3,000 would hardly be enough.

In Poland, Koczalski, who spent most of his life in France, Italy, Sweden, especially in Germany (Bad Ems, Bad Nauheim, Wiesbaden, Leipzig and Berlin), today enjoys a legendary reputation as a great Chopin player, which, according to the Polish view, is tradition the "authentic Chopin play" that he got to know from his teacher Mikuli. The possibility of comparing a large number of the recordings by various pianists available today leads to a somewhat more objective and sometimes more sobering assessment. But overall, this applies to many representatives of the older generation of pianists who were born in the 19th century and whose style of interpretation was confronted by the fifties of the 20th century with the more objective playing style of a younger generation, which was based on the original text of the composers. Soon after his death, Koczalski's name, as his wife Elsa regretfully stated in a letter in 1952, "was too much ... forgotten".

The appreciation of older pianists, which is expressed in the increasing digitization of their historical recordings, has also reached Raoul Koczalski's recordings, which are almost completely accessible. Obviously one appreciates qualities in them that modern recordings, especially of Chopin's piano works, are often lacking. This includes improvisational freedom, poetic empathy with the composer's work, sounding out the emotional content of the compositions, all of these elements that are expressed in Koczalski's playing and that are sometimes missing today in the interpretations that are too technically flawless.

Koczalski had many students. Franzpeter Goebels and Monique de la Bruchollerie from his time in Berlin should be mentioned in particular .

The composer and writer

As a composer, Koczalski created numerous works for piano solo, instrumental concerts for various solo instruments with orchestra, works for orchestra, music-dramatic works for the stage, chamber music in various formations, as well as many songs with piano accompaniment. Most of the compositions have appeared abroad (Germany, Russia, France). Koczalski's compositions are largely forgotten today. Stylistically, they can be assigned to the late Romantic period. The great upheavals in the field of contemporary music ( atonality , twelve-tone music ) that took place during Koczalski's creative period had no effect on his style. In his Chopin book from 1936 he takes a clear stand against contemporary music. He considers the experiments of the last 25 years, which "sought new paths on a cerebral, mathematical basis", to have failed and describes the representatives of modern music, whom he calls "experimenters, modernists, inventors, subversives", as "sad ghosts sadder time ”. In doing so, he agreed with the conception of art of the political class ruling in the 1930s.

Koczalski's remarks on the character and interpretation of Chopin's music remain valid, even though the style of interpretation of many modern pianists no longer corresponds to the tradition of the great Chopin players of the past. The knowledge of Koczalski's planned edition of Chopin's piano works would have been very important for the performance practice of Chopin's piano works.

The reformer

Koczalski, who, both as a pianist and as a composer, was more focused on the past, nevertheless made suggestions that have only recently been taken up and are gradually being implemented. The first concerns the professional clothing of the performing artist. In his considerations of a “lifelong” artist , he comes to the conclusion that the tailcoat can have its justification on festive occasions, but that it is impractical for a concert musician in the exercise of his profession (Koczalski was not very tall and quite stout) because it is an uncomfortable item of clothing and should be replaced by a lighter, more flowing 'garment'. Current concert practice seems to prove him right.

Koczalski also advocates darkening the hall during a concert, similar to theater and opera performances. A lamp on the wing is sufficient for lighting. This would increase the concentration on the music being performed.

Another suggestion concerns playing by heart. Many of the fears of the performing artists could be allayed if they had the notes in front of them while playing. Especially in the case of indisposition, this is an essential help and would facilitate concentration on the game. It is absolutely essential for a harmonious cooperation that in compositions for piano and orchestra both the soloist and the conductor have the notes in mind. Koczalski himself played z. B. in his last cycle of Beethoven sonatas in Posen in 1947 from the sheet music.

Koczalski also wanted to ask autograph hunters to pay. The Reichsmusikkammer should set up a collection box for those concerned in the artist's room. With the proceeds, artists in need of relaxation could have been supported.

Early in his career, Koczalski felt the urge to explain the works to be performed to his audience in introductions. He is thus one of the forerunners of today's form of the conversation concert, as it z. B. Jürgen Uhde and Franzpeter Goebels have cared for.

Works (selection)

- Compositions

- Mazurka for piano in B flat major op.6 (1891)

- Raoul. Valse for piano in G major op.18 (1889)

- Halina. Valse for piano op.19 (1890)

- Piano pieces op.40 - op.47 (1891)

- Prelude to the opera Hagar op.48 (1892)

- Piano pieces op.49 - op.52 (1893)

- Symphonic legend of King Boleslaus the Bold and Bishop Stanislaus the Holy for orchestra op.53.Pabst, Leipzig 1894

- Piano pieces op.54 - op.57 (1895)

- Rymond. Opera in 3 acts (6 images). Seal by Count Alexander Fredro. Pabst, Leipzig 1902. (Premiere: October 14, 1902 in Elberfeld)

- Mazeppa. Musical drama in 3 acts, Op. 59. Leipzig, Pabst 1905

- Ante lucem (avant l'aube). Opéra en trois actes d'après le poème de A. Fredro (père). Janin, Lyon around 1905

- Mazur for piano in C minor, Op. 60 (1895)

- The atonement. Tragedy in One Act, Op. 61. Pabst, Leipzig 1910. (Premiere: 1909 in Mühlhausen)

- Images fuyantes. 3 impressions musicales for piano op.62

- Songs for high voice and piano op.63 - op.64

- 24 Preludes pour le piano op.65 (1910)

- Song books I – IV for high voice and piano op. 66 - op. 69. Pabst, Leipzig (1909–1913)

- Piano pieces op.70 - op.71 (1912)

- 2 songs for high voice and piano op.72 (1914)

- Jacqueline. Musical comedy in 2 acts op.73 (1914)

- Sonata for violin and piano No. 1 in C minor, op.74 (1914)

- 12 impressions for piano op.75 (1914)

- Trio for violin, violoncello and piano No. 1 in D major op.76 (1914)

- Six mélodies for high voice and piano op.77 (1914)

- Evocations. Symphonie fantastique pour orchester op.78 (1915)

- Concerto for piano and orchestra No. 1 in B minor op.79

- Sonata for violoncello and piano No. 1 in B flat minor, Op. 80

- Renata. Ballet in 3 acts op.81 (1915)

- Sonata for piano No. 1 in E flat major op.82 (1914)

- Concerto for piano and orchestra No. 2 in G major op.83 (1914)

- Concerto for violin and orchestra in A major op.84 (1915)

- Concerto for Cello and Orchestra in B minor op.85 (1915)

- Pieces for violin and piano op. 86–87 (1915)

- Trio for violin, violoncello and piano No. 2 in G minor, op.88 (1916)

- Sonata for violin and piano in F sharp minor op.89 (1915)

- Sonata for violoncello and piano No. 2 in A major op.90

- Sonata for piano No. 2 in F sharp minor, Op. 91 (1916)

- Sonata for violoncello and piano No. 3 in B major op.92

- Symphony for large orchestra in F minor, Op. 93 (1920–29)

- 7 Oriental Songs for high voice and piano op.94 (around 1920)

- Sonata for piano No. 3 in G major op.95 (1919)

- Sonata for violin and piano No. 3 in A major op.96

- Sonata for piano No. 4 in G sharp minor, Op. 97

- Romantic Suite for Violoncello and Piano in B flat major op. 98 (1921-25)

- Of love. Seven poems by Rilke. Version for low voice and piano op.99 (1921)

- Of love. Seven poems by Rilke. Version for baritone and orchestra op.99 (1921)

- Sonata for piano No. 5 in D flat major, op.100

- Songs for high and low voice with piano op. 101–107

- Extreme - Orient. 3 poems by Samain for voice and piano op.108

- 2 romances (from Russian) for high voice and piano op.109

- Quattro Liriche. 4 Italian songs for high voice and piano op.110

- La Gavotta dei Bambini for piano in B flat major op.111 (1920)

- From Holland. 3 poems by Ernst Krauss for high voice and piano op.112

- Mecz miłosny. Operetta (1930)

- Sonata for violin and piano No. 4 in E major op.113 (around 1937)

- Rilke books II – V op. 114–117 for high voice and piano

- Semrud: a fairy tale from the Orient in 5 pictures and a prelude; (Text based on a fairy tale from “Thousand and One Day”, a dramatic sketch by Benno Ziegler and the comic opera “Der betrogene Kadi” by Ch. W. Gluck)., Op. 118. Tischer & Jagenberg, Cologne 1936.

- Semrud. Suite for large orchestra op.118a (1937)

- Trois Mélodies for high voice and piano op.119

- Psalm No. 121 for low voice and piano op.120

- From the west-east Divan by Goethe. 21 songs and duets for soprano and baritone op.121 (1937)

- 8 Hebbel songs for low voice and piano op.122

- Lurlei songs. 5 chants by Julius Wolff for high voice and piano op.123

- Impromptu. 5 sketches on an own theme for piano in A major op.124 (1938)

- Concerto for piano and orchestra No. 3 in C major op.125

- 5 songs for high voice and piano op.126

- Legend for piano No. 1 in C major, Op. 127. Koczalski, Berlin-Grunewald (approx. 1940)

- Rilke Book VI for high voice and piano op.128

- 3 Mirza-Schaffy-Lieder for high voice and piano op.129

- Concerto for piano and orchestra No. 4 in B flat major, op.130

- Jadis et Naguère. Suite for piano op.131 (1935–40)

- Śmiełów. Suite for piano op.132 (1938–41)

- Czerminek. Suite for piano op.133 (1938–41)

- Sonata for piano No. 6 in F minor op.134

- Trois Poèmes de E. Verhaeren for high voice and piano op.135

- Sonata for piano No. 7 in E major op.136

- 6 songs (from Russian) for high voice and piano op.137

- 4 songs for high voice and piano op.138

- Lyric Suite for Piano op.139

- Concerto for piano and orchestra No. 5 in D minor, op.140 (1942)

- 8 songs (from Russian) for high voice and piano op.141

- Romance for violin and piano in A major op.142

- Sonata for piano No. 8 in F sharp major op.143 (1943)

- Legend for piano No. 2 in E minor, Op. 144 (1943–45)

- Concerto for piano and orchestra No. 6 in E major, op.145 (1944)

- Little Sonata for piano for 2 hands in C major op.146.Koczalski, Berlin-Grunewald (ca.1942)

- 3 Nocturnes for piano op.147.Koczalski, Berlin-Grunewald (ca.1942)

- Legend for piano No. 3 in G minor, Op. 148 (1944)

- Legend for piano No. 4 in D minor, op.149 (1945)

- The extinguished light. Musical legend in 3 acts op.150 (1946)

- Concertino for oboe (or violin) and string orchestra (?. Published 1952)

- Fonts

- For Frédéric Chopin's centenary: Chopin cycle; four piano lectures along with a biographical sketch: F. Chopin, as well as the essays: Chopin as composer and Chopin as pianist, and a detailed analysis of all works intended for the performance . Pabst, Leipzig 1909.

- Frédéric Chopin. Conseils d'interprétation . Introduction by Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger. Buchet / Chastel, Paris 1998. (New edition of the French edition of the previous title, which was self-published in Paris in 1910).

- Frédéric Chopin: reflections, sketches, analyzes . Tischer & Jagenberg, Cologne 1936. (The content largely corresponds to the book from 1909).

- Considerations by a “lifelong” artist . Berlin 1937. (Printed in a brochure which, in addition to an advertisement for the Julius Blüthner piano factory, contains the announcement of a course by Koczalski in Berlin devoted to the interpretation of Chopin's piano works.)

- Koczalski's memoirs, which are in private hands, have not yet been published.

Discography (selection)

Recordings on piano rolls

- Welte , Freiburg i. Br. ( Welte-Mignon )

- Frédéric Chopin: Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21, 2nd movement, (roll No. 3974, recording 1925).

- Frédéric Chopin: Krakowiak op.14, (roll no.3975, recording 1926).

- Frédéric Chopin: Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11, (roles No. 3976, 3977, 3978, recording 1926).

- Muzio Clementi: Toccata in B flat major, (Roll No. 3971, recording 1926).

- Franz Liszt: Schumann songs, transcriptions for piano, spring night, (roll no. 3972, recording 1927).

- Franz Liszt: The linden tree. Transcription for piano after Schubert "Die Winterreise", (roll no. 3973, recording 1926).

- Richard Strauss: Sonata in B minor, Op. 5, (rolls No. 3979, 3980, recording 1925).

- Hupfeld , Leipzig ( Phonola / Triphonola )

- Frédéric Chopin: Mazurka in B flat minor op. 24/4, (roll no.12976 and roll no.55788).

- Frédéric Chopin: Mazurka in C sharp minor op. 30/4, (Roll No. 12977 and Roll No. 53590).

- Frédéric Chopin: Mazurka A flat major op. 41/3, (roll no.59339).

- Frédéric Chopin: Mazurka in F major op. 68/3 and Mazurka in F minor op. 68/4, (roll no. 59338).

- Frédéric Chopin: Nocturne in E flat major, Op. 9/2, (roll no.12978 and roll no.50099).

- Frédéric Chopin: Polonaise in A major op. 40/1, (roll no.12979).

- Frédéric Chopin: Waltz in A flat major, Op. 34/1, (Roll No. 12980 and Roll No. 56377).

- Franz Liszt: Elsa's dream. Transcription from Lohengrin by Richard Wagner, (roll no.50827).

- Franz Liszt: Song to the Evening Star. Transcription from Tannhäuser by Richard Wagner, (roll no.50750).

- Franz Liszt: Paraphrase on Ernani by Giuseppe Verdi, (roll no. 51419).

- Franz Liszt: The linden tree. Transcription from Franz Schubert's Winterreise, (Roll No. 5190)

- Frédéric Chopin: Berceuse D-flat major op.57, (roll no.10277).

- Frédéric Chopin: Impromptu No. 1 in A flat major, Op. 29, (Roll No. 10295), Impromptu No. 2 in F sharp major, Op. 36, (Roll No. 10311).

- Frédéric Chopin: Fantaisie-Impromptu No. 4 in C sharp minor, Op. 66, (Roll No. 10310).

- Frédéric Chopin: Barcarolle in F sharp major op.60, (roll no.10299).

- Frédéric Chopin: Polonaise in C sharp minor op.26/1, (Roll No. 10322)

- Frédéric Chopin: Preludes op.28 No. 4 in E minor, No. 5 in D major, No. 6 in B minor, No. 7 in A major, (Roll No. 10362), No. 16 in B flat minor, No. 17 A flat major, (roll No. 10330), No. 23 in F major, No. 24 in D minor, (roll No. 10333).

Recordings on records

Koczalski's numerous recordings are documented in the sources given and can also be researched online. They are also listed in the CD transfers booklets.

(Acoustic recordings 1924-1925)

Frédéric Chopin

- Etude in G flat major op. 10/5 (Polydor No. 62439)

- Etude in F minor, Op. 25/2 (Polydor No. 62439)

- Etude in F major op. 25/3 (Polydor No. 62439)

- Etude in C sharp minor, Op. 25/7 (Polydor No. 65788)

- Etude in G flat major op. 25/9 (Polydor No. 62439)

- Impromptu No. 1 in A flat major, Op. 29 (Polydor No. 62440)

- Nocturne in E flat major, Op. 9/2 (Polydor No. 65786)

- Nocturne in F sharp major op.15/2 (Polydor No. 65788)

- Nocturne D flat major op. 27/2 (Polydor No. 65786)

- Polonaise in A flat major op.53 (Polydor No. 62441)

- Tarantella in A flat major op.43 (Polydor No. 65790)

- Waltz in A flat major op.42 (Polydor No. 65789)

- Waltz in D flat major op.64 / 1 (Polydor No. 65789)

- Waltz in C sharp minor op.64 / 2 (Polydor No. 62440)

- Waltz in G flat major op. 70/1 (Polydor No. 65789)

- Waltz in E minor op. Post. (Polydor No. 65790)

Johann Sebastian Bach

- Gavotte and Musette, from: English Suite No. 3 in G minor BWV 808 (Polydor No. 65792)

Franz Schubert / Franz Liszt

- The linden tree (Searle 561/7) (Polydor No. 65791)

Franz Liszt

- Dream of Love No. 3 in A flat major (Searle 541) (Polydor No. 65791)

Robert Schumann

- Lonely Flowers, from: Waldszenen op. 82/3 (Polydor No. 65792)

- Waltz in A minor, from: Album Blätter op. 124/4 (Pol. 62442)

Raoul Koczalski

- Prelude in D flat major op. 64/15 (Polydor No. 65792)

- Waltz, from Renata op.81 (Polydor No. 62442)

- Impression op. 75/2 (Polydor No. 62442)

(Electrical recordings around 1928)

Frédéric Chopin

- Berceuse D flat major op.57 (Pol. 95202)

- Etude in A minor, Op. 10/2 (Pol. 90030)

- Etude in E flat minor op. 10/6 (Pol. 90028)

- Etude in F minor, Op. 25/2 (Pol. 90039)

- Etude in F major op. 25/3 (Pol. 90039)

- Etude in G sharp minor op. 25/6 (Pol. 90028)

- Etude in C sharp minor, Op. 25/7 (Pol. 95202)

- Etude from "Méthode des Méthodes" No. 1 in F minor (Pol. 90039)

- Etude from "Méthode des Méthodes" No. 3 in D flat major (Pol. 90039)

- Mazurka in B flat minor op. 33/4 (Pol. 90031)

- Mazurka in A minor op. 68/2 (Pol. 90040)

- Nocturne D flat major op.27/2 (Pol. 95172)

- Nocturne in B major op.62/1 (Pol. 95172)

- Polonaise in A major op. 40/1 (Pol. 90031)

- Prelude in E major op. 28/9 (Pol. 90038)

- Prelude in C sharp minor op.28/10 (Pol. 90038)

- Prelude in B major op. 28/11 (Pol. 90038)

- Prelude in G sharp minor op. 28/12 (Pol. 90030)

- Prelude in A flat major op. 28/17 (Pol. 95174)

- Prelude in C minor op.28 / 20 (Pol. 90030)

- Prelude in C sharp minor op.45 (Pol. 95174)

- Waltz in A minor, Op. 34/2 (Pol. 95201)

- Waltz in C sharp minor op.64 / 2 (Pol. 90038)

- Waltz in D flat major op.64 / 1 (Pol. 90030)

- Waltz in E minor op. Post. (Pol. 90029)

- Waltz in E flat major op.18 (Pol. 95201)

- Waltz in G flat major op. 70/1 (Pol. 90029)

Franz Schubert / Franz Liszt

- The linden tree (Searle 561/7) (Pol. 95349)

Ignacy Jan Paderewski

- Au Soir op.10/1 (Pol. 90040)

(Photo from Milan, around September 1930)

Johann Sebastian Bach

- Gavotte in G minor, from: English Suite No. 3 in G minor BWV 808 (Odeon O-4761b)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- German Dance in B flat major KV 600/3 (H-67736) Odeon O-25615b

- German Dance in F major, KV 602/2 (H-67736) Odeon O-25615b

Frédéric Chopin

- Berceuse D flat major op.57 (H-2-58051) Homocord D-12035b

- Etude in G flat major op. 10/5 (H-67731) Odeon O-25615a

- Etude in F minor op. 25/2 (H-67735) unpublished

- Etude in F major op. 25/3 (H-67735) unpublished

- Prelude in A major op. 28/7 (H-67740) Odeon O-4761a

- Prélude D flat major op. 28/15 (H- 2-58050) Homocord D-12035a

- Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor op.35, 3rd movement (funeral march) (H-67732 and H-67733) Homocord 4-3955

- Waltz in D flat major op.64/1 (H-67740) Odeon O-4761a

(Photo taken in Berlin, March 17, 1937)

Frédéric Chopin

- Three Ecossaises op. 72 / 3-5 (HMV DA4431)

- Mazurka in F major op. 68/3 (HMV DA44309)

- Nocturne in F sharp major op.15/2 (HMV DA44309)

- Polonaise in A flat major op.53 (HMV DA4431)

- Scherzo in B flat minor op.31 (HMV DB4474)

(Recordings 1938-1939)

Frédéric Chopin

- Ballade No. 1 in G minor, Op. 23 (Pol. 67528, recording: Berlin, November 17, 1939)

- Ballad No. 2 in F major op.38 (Pol. 67531, recording: Berlin, June 19, 1939)

- Ballade No. 3 in A flat major op.47 (Pol. 67529, recording: Berlin, June 19, 1939 and November 17, 1939)

- Ballade No. 4 in F minor op.52 (Pol. 67530, recording: Berlin, June 19, 1939)

- Berceuse D flat major op.57 (Pol.67246A, recording: Berlin, June 28, 1938)

- 12 Etudes op.10 (Pol. 67262–67264, recording: Berlin, June 29, 1938)

- 12 Etudes op. 25 (Pol. 67242–67245, recording: Berlin, June 29, 1938)

- 3 etudes from "Méthode des Méthodes" (Pol. 67244, recording: Berlin, June 29, 1938)

- Fantaisie-Impromptu in c sharp minor op.66 (Pol.67248B, recording: Berlin, June 29, 1938)

- Impromptu in F sharp major op.36 (Pol.67248A, recording: Berlin, June 29, 1938)

- Nocturne in E flat major op.9/2 (Pol.67246B, recording: Berlin, June 28, 1938)

- Nocturne in B major op.32/1 (Pol.67534B, recording: Berlin, November 17, 1939)

- Nocturne in C minor, Op. 48/1 (Pol.67534A, recording: Berlin, November 17, 1939)

- 24 Préludes op. 28 (Pol. 67505–67509 Recording: Berlin, June 10, 1939)

- Prélude in A flat major (Presto con leggerezza) (Pol.67509A Recording: Berlin, June 12, 1939)

- Prélude in C sharp minor op.45 (Pol.67509B, recording: Berlin, June 10, 1939)

- Waltz in E flat major, Op. 18 (Pol.67515A, recording: Berlin, June 12, 1939)

- Waltz in A flat major op.34/1 (Pol.67247A, recording: Berlin, June 28, 1938)

- Waltz in A minor op.34/2 (Pol.67515B, recording: Berlin, June 12, 1939)

- Waltz in F major op. 34/3 (Pol.67533A, recording: Berlin, June 10, 1939)

- Waltz in D flat major op.64 / 1 (Pol.67533A, recording: Berlin, June 10, 1939)

- Waltz in A flat major, Op. 64/3 (Pol.67533B, recording: Berlin, June 10, 1939)

- Waltz in A flat major op.69.1 (Pol.67247B, recording: Berlin, June 28th, 1938)

- Waltz in G flat major op. 70/1 (Pol.67533B, recording: Berlin, June 10, 1939)

- Mewa, Poznan

Frédéric Chopin

- Berceuse D flat major op.57 (Mewa 30b, recording: Posen 1948)

- Ecossaises op. 72 / 3–5 (Mewa 31b, recording: Posen 1948)

- Mazurka in F major op. 68/3 (Mewa 31b, recording: Posen 1948)

- Nocturne in E flat major op.9/2 (Mewa 33b, recording: Posen 1948)

- Nocturne in F sharp major op 15/2 (Mewa 25b, recording: Posen 1948)

- Nocturne in B major op.32/1 (Mewa 33a, recording: Posen 1948)

- Nocturne in G minor op.37/1 (Mewa 35a, recording: Posen 1948)

- Prélude in A major op. 28/7 (Mewa 30a, recording: Posen 1948)

- Prélude D flat major op. 28/15 (Mewa 34a, recording: Posen 1948)

- Prélude in A flat major op. 28/17 (Mewa 34b, recording: Posen 1948)

- Waltz in E flat major op.18/1 (Mewa 31a, recording: Posen 1948)

- Waltz in A flat major op. 34/1 (Mewa 32a, recording: Posen 1948)

- Waltz in A minor op. 34/2 (Mewa 32b, recording: Posen 1948)

- Waltz in C sharp minor op.64 / 2 (Mewa 30a, recording: Posen 1948)

Broadcast recordings

Transfer of records and radio recordings to CD

- Koczalski plays Chopin. Broadcast recordings from German radio. 1945 and 1948 . Music and Arts, 2012. CD-1261.

- Raoul Koczalski plays Chopin . Biddulph Recordings, 1994. LHW 022

- Raoul von Koczalski: Chopin. Enregistrations 1929–1941 . Dante Productions, 1996. HPC042.

- Raoul Koczalski plays Chopin . Pearl, 1990. GEMM CD 9472.

- Raoul von Koczalski 1894–1948 . (Wrong date of birth!). Archiphon, 1977. ARC-119/20. (Contains recordings by Chopin, Mozart, Paderewski, Tchaikovsky, Rubinstein, Mussorgsky, Scriabin, Szymanowski, Rachmaninow, Bartók and Koczalski).

- The complete Raoul von Koczalski . Vol. 1. The Polydor recordings 1924-1928. Vol. 2. Homochord, Electrola and Polydor recordings 1930-1939. Marston Records, 2011. Marston 52063 and 53016-2.

- Raul Koczalski: pianista i kompozytor . Vol. 1-8. Selenium, Warsaw. (Also includes piano compositions and songs by Koczalski).

- Legends of the piano. Acoustic recordings 1901-1924 . Naxos Historical 8.112054. Contains u. a. : Frédéric Chopin: Polonaise No. 6 in A flat major, Op. 53 played by Raoul Koczalski.

literature

- Wilhelm Spemann: Spemann's golden book of music . W. Spemann, Berlin / Stuttgart 1916, p. 702.

- Bernhard Vogel: Raoul Koczalski: Sketch . Pabst, Leipzig 1896.

- Stanisław Dybowski: Raul Koczalski: chopinista i kompozytor . Selene, Warszawa 1998, ISBN 83-910515-0-1 .

- Teresa Brodniewicz et al. a .: Raul Koczalski (Series: Biography). Akademia Muzyczna im. Ignacego Jana Paderewskiego w Poznaniu, Poznań 2001, ISBN 83-88392-25-5 .

- Ingo Harden u. Gregor Willkes (collaboration: Peter Seidle): Pianist profiles . Bärenreiter, Kassel 2008. pp. 388/389.

- MGG (= music in the past and present ) . Bärenreiter, Kassel 1958. Vol. 7, column 1302.

- MGG (= music in the past and present ) . 2nd revised edition. Bärenreiter / Metzler, Kassel et al. 2003. Person Teil Vol. 10, S. 387a.

- Article Koczalski in the Polish Wikipedia.

- Raoul Koczalski: Frédéric Chopin. Conseils d'interprétation . Introduction by Jean-Jacques Eigeldinger. Buchet / Chastel, Paris 1998.

Remarks

- ↑ The resulting financial problems troubled Koczalski until shortly before his death. It is quite possible that his return to Poland at the end of the Nazi dictatorship from which he suffered, and the assumption of a professorship at the Music Academy in Poznan, despite another dictatorship, this time from the communist regime, is related to the desire for financial security .

- ↑ Heinrich Burk: This is my city. Bad Nauheim stories from a hundred years . Verlag der Buchhandlung am Park, Nauheim 1995. pp. 76–82.

- ↑ In this concert Koczalski played Ludwig van Beethoven's piano sonata in C sharp minor op. 27/2, the so-called moonlight sonata and piano pieces by Frédéric Chopin. Paul Hartmann recited from Goethe's Faust . It is not known whether the selection of the piano pieces came from Koczalski or was prescribed by a higher authority. The officers present had been summoned to Berlin for a special mission in the last year of the war. The purpose of the cultural event was to serve as a pre-mission edification, but it was known that "Moonlight Sonata" was the code name for the devastating bombing of the English city of Coventry on the night of November 14th to 15th, 1940.

- ↑ There is a tendency in Polish literature to portray Koczalski as a person persecuted by the National Socialists, who continued to cultivate Polish music underground. This view needs correction. It can be assumed that the private activities of Koczalski were known to the authorities and were tolerated. There are also advertisements in the guide through the concert halls of Berlin in which Koczalski publicly advertises his piano and theory lessons in 1942. The rise of Koczalski after 1934, especially in Berlin, may be related to his arch-conservative views on modern music that coincided with those of the Nazis. He was aware of the expulsion of the Jewish musicians from Berlin (dismissal, emigration, deportation) as well as the "de-Judaization" of the Reich Music Chamber . This also applies to the so-called Poland Action in 1938. In the endeavors of the National Socialists to get Poland on their side, he was a valued representative of Polish culture. Goebbels writes in his diary (vol. I / 4, p. 109) on April 24, 1937: “Piano concertos [t] Koczalski. He plays Schumann and Chopin wonderfully. A pure pleasure. Still a German-Polish evening in the KddK (= comradeship of German artists. Author's note). ”After the outbreak of World War II, the bestial treatment of Polish prisoners of war and forced laborers as“ Slavic subhumans ”could not have remained hidden from Koczalski. No public statements by Koczalski in favor of his compatriots are known.

- ↑ Doc. Orig. Koczalski 65-71. Doc. 69 at the State Institute for Music Research Berlin.

- ↑ Signature SM 08.

- ↑ Designation: N.Mus. Estate 139 (Koczalski estate).

- ↑ Roles mainly for Welte-Mignon, Pleyela, Triphonola, records for u. a. Homochord, Polydor, Odeon, Electrola, Mewa.

- ↑ Many recordings were posted on youtube.

- ↑ It was announced under the edition numbers ED 5811–5822. According to the publisher, the archive in Leipzig was destroyed in the Second World War, so that the prehistory of the Chopin edition remains unclear.

- ↑ Recordings were also made on the Steinway grand piano.

- ^ Raoul Koczalski: Frédéric Chopin. Considerations. Sketches. Analyzes . Tischer, Cologne 1936. p. 12.

- ↑ James Methuen-Campbell: Chopin playing. From the composer to the present day . Gollancz, London 1981.

- ↑ Claudio Arrau: Living with Music . Recorded by Joseph Horowitz. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1987. p. 181.

-

↑

"An ex-child prodigy who was covered with medals when he was six, some of them hanging on his little bottom; he lived in Germany and developed into a very bad pianist. "

"A former child prodigy who was covered with medals at the age of six, some of which were hanging down to his little bum, he lived in Germany and turned out to be a very bad pianist."

- Arthur Rubinstein: My many years . Jonathan Cape, London 1980, p. 439 - ^ Letter of March 3, 1953 to Franz Herzfeld. Estate of the Koczalski State Library in Berlin.

- ^ Raoul Koczalski: Frédéric Chopin: considerations, sketches, analyzes . Tischer & Jagenberg, Cologne 1936, p. 4.

- ↑ This list was compiled from the catalog of the Berlin State Library and from Stanisław Dybowski: Wykaz kompozycji Raula Koczalskiego , in: Teresa Brodniewicz u. a .: Raul Koczalski . Akademia Muzyczna im. IJ Paderewskiego w Poznaniu, Poznań 2001.

- ↑ Complete directory: Stanisław Dybowski: Wykaz nagrań Raula Koczalskiego. In: Teresa Brodniewicz u. a .: Raul Koczalski . (Series: Biography). Akademia Muzyczna im. IJ Paderewskiego w Poznaniu, Poznań 2001. pp. 85-93. Also contains a list of Koczalski's works on CD ( Dyskografia utworów Raula Koczalskiego pp. 92–93).

- ↑ Gerhard Dangel and Hans-W. Schmitz: Welte-Mignon piano rolls. Welte-Mignon Piano Rolls . Self-published, Stuttgart 2006. p. 464.

- ^ Albert M. Petrak (Ed.): Pleyela Piano Roll Catalog . The Reproducing Piano Roll Foundation. Mac Mike 1998.

- ↑ Armand Panigel (ed.): L'œuvre de Frédéric Chopin. Discography générale . Édition de la Revue Disques, Paris 1949. p. 250.

- ^ Francis F. Clough / GJ Cuming: The World's Encyclopaedia of recorded music (= WERM) . Greenwood Press, Westport 1970. (Reprint).

-

^ Biblioteca Narodowa Warszawa. Zakład zbiorów dźwiękowych i audiowizualnych. Historical recordings:

Raul Koczalski. Access at: http://www.bn.org.pl/chopin/index.php/pl/pianists/dysk/14

Web links

- Literature by and about Raoul Koczalski in the catalog of the German National Library

- Sheet music and audio files by Raoul Koczalski in the International Music Score Library Project

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Koczalski, Raoul |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Koczalski, Armand Georg Raoul von; Koczalski, Rauul; Koczalski, Raoul de; Koczalski, Raul; Amando, Jerzy (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Polish pianist and composer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 3, 1885 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Warsaw |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 24, 1948 |

| Place of death | Poses |