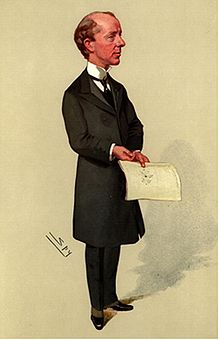

Reginald McKenna

Reginald McKenna (born July 6, 1863 in Kensington , London , † September 6, 1943 ) was a British statesman and banker. McKenna held numerous ministerial posts in the Campbell-Bannerman and Asquith administrations between 1907 and 1916, before heading the operations of the largest banking house in the United Kingdom from 1919 to 1943 as Chairman of the Board of Directors of Midland Bank .

Biography and career

McKenna's early life (1863-1887)

McKenna was born as the fifth and youngest son of Irish-born London tax officials William Columban McKenna (1819-1887) and his wife Emma Hanby († 1905). On his father's side, he was a nephew of the influential banker Josef McKenna. McKenna was raised Protestant and confessionally confessed to congregationalism .

Due to the family's financial difficulties after the "Overend Gurney bank failure" of 1866, McKenna was sent to France with his mother and younger siblings in 1866 by the father, who remained in London, where the cost of living was significantly lower than in Great Britain. From 1869 to 1874 he attended school in Saint-Malo in France and from 1874 to 1877 in Ebersdorf in Germany, so that he later became fluent in both national languages. He completed his school career at King's College School in London.

As a young man he attended the University of London and Trinity Hall , one of the most prestigious colleges of the University of Cambridge , where he obtained a diploma in mathematics in 1885, which he considered one of the "senior optimes", i.e. H. was awarded to one of the best of the year. In 1916 he was elected an honorary fellow at Trinity Hall. In addition to his academic merits McKenna was able to record during his student years, various sporting success: During his last year at Cambridge, he belonged to the famous rowing team at the University of with which he in 1887 in held annually Boat Race Oxford against Cambridge , the team of University of Oxford defeat and with which he also won the Grand Challenge Cup at the Henley Royal Regatta in 1886 and the Stewards' Challenge Cup in 1887 .

Career as a lawyer and parliamentarian (1887–1905)

From 1887 to 1895 McKenna worked as a lawyer and ran a successful law firm. In 1892 McKenna ran unsuccessfully as a candidate for the Liberal Party in the Clapham constituency for a seat in the British House of Commons . In the general election of 1895 he was finally elected as a Member of Parliament for the district of North Monmouthshire . There McKenna was first noticed as a member of a small group of the "radicals" (ie the left wing of the Liberals), which rallied around the experienced politician Charles Dilke , one of the leading men of the Liberals in the House of Commons. On Dilke's advice, the young McKenna finally began to look for a special topic that he should delve into in such a way that he, as an authority on the subject, would be given increased attention: the topic he finally decided on was collective bargaining policy, in which he quickly became one of the experts in his party. In addition, he emerged - as a member of a Welsh constituency only logically - especially in debates on matters related to Wales, such as the Education Bill of the Conservative government of 1897. McKenna's attacks on the latter, which he attacked together with David Lloyd George , who was his close friend and colleague at the time, brought him greater publicity for the first time.

During the Boer War (1899–1902) McKenna was one of the most violent critics of the conservative government and the war in general. On the side of party leader Campbell-Bannerman and Lloyd Georges, he belonged to the radical wing of the liberals, which opposed the war, in contrast to the imperialist wing, around Asquith , Haldane and Primrose , which approved the war.

In 1903 McKenna was one of the co-founders of the Free Trade Union, which fought for the continued existence of the British free trade system. In parliament he stood out at that time as a staunch opponent of the protectionist plans of the conservative Colonial Minister Joseph Chamberlain . In a much-admired speech in 1904, for example, he attacked the discriminatory tobacco tariffs introduced by Chamberlain's son, Austen Chamberlain , against foreign imports of tobacco products. Together with Lloyd George and Dilke, McKenna also fought for a “redynamization” of the slack parliamentary liberalism.

In Parliament, despite their differences during the Boer War, McKenna finally became one of the closest collaborators of Herbert Henry Asquith, the "rising star" and future party leader of the Liberals: In addition to Richard Haldane and Sir Edward Gray , he is considered to be most Asquith biographers - such as Roy Jenkins - as the most important intimate of the liberal statesman during his time as prime minister (1908–1916) and in Asquith's first years as leader of the liberal opposition after his overthrow (around 1916–1922 / 1923), before their ways in the early 1920s parted.

Liberal Minister (1905-1916)

After his rise in the Liberal Party, McKenna served as Undersecretary of State and Minister in the Liberal Governments of Henry Campbell-Bannerman and Herbert Henry Asquith from 1905 to 1916 : from 1905 to 1907 as Undersecretary of State in the Treasury, from 1907 to 1908 McKenna served as Minister of Education ( President of the Board of Education ), then, after Asquith he became prime minister from 1908 to 1911 as Secretary of the Navy ( First Lord of the Admiralty ), from 1911 to 1915 as Minister of the Interior ( Home Secretary ) and finally in the second cabinet Asquith (the coalition cabinet with the conservatives which was formed in 1915 in view of the dramatic war situation) 1915-1916 as Chancellor of the Exchequer ( Chancellor of the Exchequer ).

After the overthrow of the Conservative government under Arthur James Balfour in December 1905, McKenna, under the patronage of Asquith, then the second man in the Liberal Party, became a candidate for ministerial almost immediately. After the inauguration of the Liberals, he came as a steward of Asquith, who as Chancellor of the Treasury took over the second most important government office, first with the latter in the Treasury, where he acted as Secretary of State from 1905 to 1907 after Winston Churchill had turned down this post in favor of the Secretary of State in the Colonial Ministry .

After the overthrow of the education minister Augustine Birrell in 1907 in the course of the debate on the education bill, he was finally able to move up to a ministerial office.

Navy Minister (1908-11)

In April 1908 McKenna took over as the successor to Edward Marjoribanks, 2nd Baron Tweedmouth , the office of Minister of the Navy, where he was the first holder of this post who did not sit in the House of Lords - i.e. was not a nobleman - but held a seat in the House of Commons. His appointment came as a result of the government reshuffle that followed the resignation of Prime Minister Henry Campbell-Bannerman from government responsibilities in 1908 and the inauguration of Herbert Henry Asquith as head of government. Research today assumes that Asquith had intended his satrap to be Chancellor of the Exchequer in his government, but had to transfer this office to Lloyd George under pressure from the party links.

Together with the First Sea Lord John Fisher, McKenna, as Minister of the Navy from 1908 to 1911, pushed for a social reform of the Royal Navy (easier access to the marine colleges for less privileged applicants, etc.), and in particular the construction of large battleships , so-called dreadnoughts (named after the name of the first ship), in order to guarantee a sufficient numerical and qualitative superiority of the British fleet compared to the German risk fleet built at the same time under the aegis of Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz . The failure of the German risk strategy, which aimed to deter the United Kingdom from anti-German engagements in a European war ( to attach a considerable risk of its own to such engagements ) by making it aware of the danger that a Assumption command of a German fleet that was inferior to the British fleet but still heavily developed, would cause the Royal Navy such high losses that Britain would lose its supremacy at sea to a third power after a victory over the German Empire, is not least McKenna's efforts owed as Minister of the Navy. Although the weakening of the British state by the First World War enabled the Americans to at least catch up with the British in terms of the fleet.

In the internal cabinet discussions and the parliamentary debates about the use of tax revenues in favor of expanding the welfare state or in favor of the construction of more dreadnoughts, McKenna appeared as a staunch advocate of further armament. David Lloyd George and Winston Churchill, who at the time formed a successful political tandem as finance and trade ministers, respectively, appeared as his main adversary in the quarrels about the use of tax revenues. Lloyd George and Churchill, at that time representatives of the outer left wing of the Liberal Party, at the time believed McKenna's concerns, who was regarded as a representative of the right, about the expansion of the German fleet to be absurd. Instead of investing the money in the construction of ships, they favored using the money to expand pension, health and accident insurance for the less well-off social classes.

It is now believed that McKenna, alongside Fisher and the Conservative press, played a leading role in initiating the Naval Scares and Invasion Scares of 1909, a press campaign that eroded the British people's fears of losing British maritime supremacy and even one Invasion of Great Britain by the German Reich and led to a further deterioration in German-British relations in the run-up to the First World War. Conversely, the political climate triggered by this campaign favored the willingness of politicians and the public to submit to McKenna's wishes for armaments.

In the power struggle within the naval leadership between Fisher and Lord Charles Beresford , McKenna sided with Fisher, which is why the latter gave him the appreciative nickname "fighting Mac", under which he was known in public for a long time.

After Fisher's departure as chief of the fleet in January 1910, Admiral Sir Arthur “Tug” Wilson succeeded him in this position. Wilson's arrogant and traditional style of leadership led to a freezing of the reform process of the Navy, which the conflict-averse McKenna was unable to avert. Moreover, after the Navy had failed to come up with a war plan in the Agadir Crisis of 1911 , which had brought Europe to the brink of world war (Wilson, caught in the autocratic mentality of a Victorian fleet commander, preferred war plans in his “head” rather than not in the "vaults" of the Admiralty), the Prime Minister released the binding McKenna from the office of Minister of the Navy. His place was taken by Asquith's considered assertive young cabinet colleague Winston Churchill , who had changed from the left to the right wing of the party during the Agadir crisis and who succeeded McKenna on October 25, 1911.

Minister of the Interior (1911-14)

McKenna took over the Interior Ministry, which had become vacant, in Churchill's place. In this role he played a key role in drafting the Home Rule , which granted Ireland extensive national sovereignty in July 1914. However, the law was suspended due to the outbreak of World War I.

He also drafted the so-called "cat and mouse law", which in the following years became the guideline in the fight against the aggressive suffragettes who acted with militant means . This provided for the release of hunger strikers imprisoned suffragettes from custody as soon as there was a health risk, but to take them back into custody immediately if the health risk no longer existed.

Chancellor of the Exchequer (1915-1916)

In May 1915 McKenna was briefly under discussion (inter alia at the intercession of Fisher) as the successor to Winston Churchill in the office of Minister of the Navy, after the latter had fallen as First Lord of the Admiralty due to the failure of the Dardanelles operation and temporarily in the sinecure of the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster , a minor government agency, had been deported.

After the formation of a coalition government in June 1915, however, this office went to the former Prime Minister Arthur Balfour. McKenna was instead named Chancellor of the Exchequer, the British government's second most important post in peacetime.

As Chancellor of the Exchequer, McKenna was responsible, among other things, for the further transition of the British economy from a peace economy to a war economy and the fivefold increase in income tax to fund the war effort. To finance the war effort, he drastically increased income tax, introduced high sales taxes on groceries such as sugar, tea, and coffee, and taxed many other goods and areas of life (including train tickets, amusements, and top profits). Taxes on certain profits reached up to 60%.

As a supporter of Asquiths and an opponent of conscription, which he rejected for moral reasons and as an impairment of the efficiency of the British war economy, he left the government after Asquith's fall in December 1916 and his replacement by David Lloyd George . As a supporter of the Asquith wing of the Liberal Party, he was among the leaders of the "loyal" opposition in the House of Commons for the remainder of the war.

Chairman of Midland Bank (1919–1943)

McKenna had been appointed to the board of directors of Midland Bank in parallel to his post as parliamentarian since April 1917. After he had lost his seat in the House of Commons in the House of Commons elections of December 1918 - in which he had had a bad starting position as a member of the "renegade" Asquith wing of the Liberal Party, which had been split since May 1918 - McKenna was appointed Chairman of the Board of Directors of Midland Bank in 1919 - an office that he should hold for the rest of his life.

After losing his mandate from the House of Commons, McKenna served from 1919 until his death in 1943 without interruption and extremely successfully as Chairman of the Board of Directors of the London Joint City and Midland Bank, the largest bank in the world at the time.

In 1922 the newly appointed Conservative Prime Minister Andrew Bonar Law offered him again the office of Chancellor of the Exchequer, which McKenna refused. In 1923 Law's successor Stanley Baldwin , who had previously been Chancellor of the Exchequer in the short-lived Law government and who continued to act as Chancellor of the Exchequer in addition to his own official business as Prime Minister, repeated his predecessor's offer to McKenna to appoint him Chancellor of the Exchequer, which this time more inclined to accept this. In 1924, in anticipation of his soon-to-be Chancellor of the Exchequer, he graced the cover of the American Times magazine. However, since McKenna insisted to belong to the Parliament as a member of the City of London and no mandate holder was willing to give up his seat in Parliament in favor of McKenna, McKenna renounced the office of Chancellor of the Exchequer. Instead, Neville Chamberlain became Chancellor of the Exchequer.

In the following years McKenna was offered a number of peer dignity , which he refused until his death. In the 20s and 30s McKenna figured as unofficial advisor to the Chancellors of the Exchequer Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain, Philip Snowden and Winston Churchill. He advised this, among other things, during the negotiations with the United States 1922-23 over the British war debts. In addition, McKenna - as England's leading banker and one of the most important figures in public life - acted as an advisor to numerous other personalities. For example, he was consulted by his friend Max Aitken during his “Empire Crusade” in 1930.

He saw the British reparations claims against Weimar Germany as too burdensome for the defeated war opponent. Following this view, McKenna chaired the most important committees of the revisionist Dawes Commission in 1924 and co- authored the report alongside Charles G. Dawes , which was published at the end of the commission's sessions. The Dawes Plan , presented after the work of the Dawes Commission, significantly reduced the reparations burden of the German Reich after its ratification by all parties involved.

Although he considered it “unprofitable” to treat the communist and fascist powers of Europe as “lepers”, McKenna was very uneasy about the appeasement policies of the Baldwin and Chamberlain administrations in the 1930s.

McKenna died in 1943 at the age of 80 and still in the office of Chairman of the Board of Directors of Midland Bank. He was cremated and buried near his country home in Mells Park, Somerset .

Family and personal life

In 1908 McKenna married Pamela Jekyll († 1943), the daughter of Sir Herbert Jekyll, who was considered one of the most beautiful women in London society at the time. The marriage resulted in two sons: Michael († 1931) and David. The latter married Lady Cecilia Keppel in 1934.

Political importance

McKenna is still a shadowy figure for historiography today. Roy Jenkins , a successor to McKenna in the offices of Minister of the Interior and Chancellor of the Exchequer and also son of the “heir” of McKenna's constituency in North Monmouthshire, complained in his biography of Stanley Baldwin that in his eyes McKenna had “as much substance (tangibility) as the encrusted ones Wings of a butterfly ”. Cregier stated in Oxford "National Biography" that the majority of historians McKenna as an "elusive" ( elusive ) and therefore difficult considers to be assessed figure, which he attributes to the fact that McKenna left to posterity a few personal documents and never wrote down his memoirs. The historian Martin Farr, who is currently working on a biography of McKenna, has set himself the task of closing this "most important gap in British political history of the 20th century".

His cabinet colleagues - even his adversary Lloyd George - and his subordinate officials praised McKenna's ability as an administrator during their time together and in retrospect. Critics, on the other hand, criticized his lack of political instinct and his lack of flexibility, which led to the loss of his post as Minister of the Navy in 1911 and which he had given to Asquith, v. a. in the December crisis of 1916 - contributed to the decline of the Liberal Party.

On the other hand, the research also indicates that McKenna was one of the few contemporaries who had had the visionary power after the end of the First World War to clearly see and recognize the actual results and consequences of the war. He was one of the first to recognize that the successes achieved in the war, such as the Treaty of Versailles and the acquisition of new colonial territories, were deceptive, and he pointed out the untenability of Great Britain's great power congestion long before the inconspicuous decline was also generalized such was rated.

Works

- Post-War Banking Policy. 1928.

estate

The Papers of Reginald McKenna

- Location: Churchill Archives Center

- Reference: GBR / 0014 / MCKN

- Scope: 52 archive boxes

- Period: 1883, 1994, mainly 1900–1943.

- Content:

- Three main groups

- Personal documents (MCKN 1)

- Public Affairs (MCKN 2–5)

- General (MCKN 6–7)

- Single content

- MCKN 1: Personal Papers

- MCKN 2: Education Board Papers

- MCKN 3: Admiralty Papers

- MCKN 4: Home Office Papers

- MCKN 5: Exchequer Papers

- MCKN 6: Fisher Correspondence

- MCKN 7: Later Career

- Three main groups

literature

Biographies

- Martin Farr: Reginald McKenna 1863-1943: A Life. London 2004, ISBN 0-7146-5047-1 .

- Samuel Herman Jenike: Reginald McKenna: The Pre-war Years, a Political Biography. s. l. 1968.

- Stephen McKenna: Reginald McKenna, 1863-1943. London 1948. [biography written by McKenna's nephew]

Biographical sketches

- Earl of Birkenhead: The Right Hon. Reginald McKenna. In: Contemporary Personalities. London 1924, pp. 215-222.

- DM Cregier: "McKenna, Reginald". biographical entry In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Volume 35, New York 2004, pp. 541-545.

Technical articles

- Robin S. Betts: Winston Churchill and the Presidency of the Board of Education, 1906-7. In: History of Education. 15 (2), 1986, pp. 89-93. ISSN 0046-760X [documents reasons for McKenna's preferred entry into the cabinet over Churchill]

- Martin Farr, A Compelling Case for Voluntarism: Britain's Alternative Strategy, 1915-1916. In: Was in History. 9 (3), 2002, pp. 279-306. ISSN 0968-3445

Contemporary pamphlets

- Frank Soddy: The arch-enemy of ecomonic freedom: what banking is, what first it was, and again should be. A reply to Mr. McKenna's 'What is banking?' including a criticism of the Morgenthau and Keynes proposals and a résumé of the author's monetary reform proposals for £ for £ banking. Enstone 1943.

Web links

- Literature by and about Reginald McKenna in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Reginald McKenna in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

Remarks

- ↑ Because of his close relationship with his mentor Dilke, the press called McKenna Dilkes "his Man Friday" during those years.

- ↑ According to the ODoBB, McKenna owned 89,948 pounds, 1s and 4d at the time of his death.

- ↑ ODoNB, Volume 35, p. 545.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Edward Marjoribanks |

First Lord of the Admiralty 1908–1911 |

Winston Churchill |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | McKenna, Reginald |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British politician, member of the House of Commons |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 6, 1863 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 6, 1943 |

| Place of death | London |