Sandgate Castle

Sandgate Castle is an artillery fort that King Henry VIII had built in Sandgate in the English county of Kent in 1539–1540 . It formed part of the royal Device Fort program designed to protect England from invasion from France and the Holy Roman Empire and to defend vulnerable points along the coast. The fort consisted of a stone donjon in the middle, three additional towers and a gatehouse . Four rows of artillery could be stationed there and it was equipped with 142 gun emplacements for cannons and small arms.

Sandgate Castle was captured by the parliamentarians in 1642, at the beginning of the English Civil War , and conquered by royalist rebels towards the end of the Civil War in 1648 . Between 1805 and 1808, during the coalition wars , the fort was fundamentally rebuilt. Its height was significantly reduced and the donjon was converted into a Martello tower . After the work was finished, the fort was equipped with ten 24-pounder cannons and the garrison strength was 40 men.

Since the early 17th century, Sandgate Castle suffered from coastal erosion and by the mid 19th century the retreating coastline had reached the edge of the castle walls. The high cost of the necessary repairs contributed to the government's decision to sell the fort in 1888. Initially, a British railway company bought Sandgate Castle, then it passed into private hands. Coastal erosion continued and by the 1950s the southern part of the castle had been destroyed by the sea. The remaining fort was restored 1975-1979 at the instigation of Peter and Barbara McGregor and served them as a private residence. Sandgate Castle is still privately owned and English Heritage has listed it as a Grade I Historic Building.

history

16th Century

Sandgate Castle was built as a result of international tensions between England, France and the Holy Roman Empire during the final years of Henry VIII's reign. Traditionally the Crown had left coastal defense to the local lords and communities and only played a modest role in the construction and maintenance of coastal fortresses. While France and the Holy Roman Empire were in conflict, raids on England by sea were common, but an invasion of England appeared unlikely. Modest fortifications, such as simple log houses or towers, existed in south-west England and along the Sussex coast ; a few more impressive castles were in the north of England, but in general the fortresses were not very large.

In 1533 King Heinrich broke with Pope Paul III. about the annulment of his long marriage to Catherine of Aragon and another marriage. Katharina was an aunt of the Spanish King Charles V and he saw the annulment of the marriage as a personal insult. This led to an alliance between France and the Holy Roman Empire against King Henry in 1538 and the Pope encouraged the two countries to attack England. An invasion of England seemed certain. In response, King Heinrich issued an order (English: Device), which contained orders to "defend the empire in times of invasion" and to build forts along the English coast.

Sandgate Castle was designed to defend a vulnerable point on the Kent Cliffs, just west of Folkestone . It was feared that an enemy force could land there and easily penetrate inland. The construction of Sandgate Castle was overseen by the Moravian civil engineer Stephan von Haschenperg and Thomas Cockys and Richard Keys acted as commissioners for the project. In the first construction phase in 1539, a team of 237 men, including bricklayers, quarry workers, lime burners and lumberjacks, were employed to prepare the building site. The masons came as far as Somerset and Gloucestershire . In the summer over 500 people were already employed, unskilled workers, bricklayers, joiners and sawmills. After a break in the winter months, work was resumed in the summer of the following year; in July 630 men were working on the castle.

The foundations of the castle were built on the pebble beach below. The walls consisted of ragstone (hard, Kentish limestone), which was mostly laid roughly one on top of the other, with some work being carried out in finer stone and the details in Pierre de Caen . Most of the ragstone was extracted from the local beaches where there were suitable ledges to the west and east of the site. 459 tons of Pierre de Caen were won from the Christ Church and Horton priories , which had recently been dissolved by King Henry . A total of 147,000 bricks were used, which were made in 13 different brick factories, as well as 44,000 flagstones, mostly made in Wye , 1,859 truckloads of lime , 110 tons of coal and 979 tons of lumber. The total cost of the project was £ 5,584.

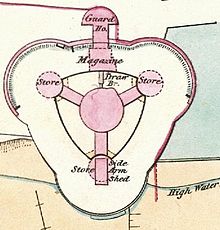

In the middle of the new castle stood a donjon with a circular floor plan, surrounded by three towers with an oval floor plan, bastions to the northwest, northeast and south and a gatehouse on the north side. This ensemble was surrounded by two curtains that formed a triangular core and outer bailey. Covered stone corridors, three stories high, connected the towers, the donjon and the gatehouse. The outer courtyard was covered with grass and had a stone septic tank next to the northeast tower, which was connected to the inner castle by underground pipes. The interior of the castle was accessible via a door on the back of the gatehouse, which was originally called the “half moon” and which was connected to the donjon by a staircase inside a corridor. There were four rows of guns in the finished castle, from the ground floor to the roof of the donjon, a total of 142 gun emplacements for cannons and small arms. The layout corresponded to that of the nearby Walmer Castle and Deal Castle .

Sandgate Castle was completed in the fall of 1540. King Henry may have visited the castle on the occasion of his visit to Folkestone in May 1542. Queen Elizabeth I visited the fortress in 1573 and also used it to imprison the courtier Thomas Keyes for a time after he had married Lady Mary Gray against the wishes of the queen. It is recorded that in 1593 the fortress was equipped with seven pieces of artillery: a field snake , two half field snakes, three small field snakes, and a minion , along with muskets , arrows, and bows.

17th and 18th centuries

In 1609 the garrison consisted of a captain and his lieutenant, five soldiers, two porters and ten riflemen. The mortar that was used to build the fort was particularly poor and was showing signs of deterioration as early as 1616. A condition report from that year showed that the fort was already clearly dilapidated; the repair cost was estimated at £ 260. It is also reported that its 30-meter-wide gun platform for 10 cannons was built along the south wall, which replaced the previous south battery. A condition report from 1623 mentions the same problems and also that the coastal erosion caused 1/3 of the south wall to collapse; repairs now needed including reinforcement of the walls were estimated at £ 560.

Four years later, the captain of the fort, Richard Chalcroft, amid fears of war with France and Spain, reported that the fortress was in such poor condition that it was “neither habitable nor defensible against any attack, and certainly not in a position be to protect the streets ”. An inspection team found that it was easy to climb the ruinous walls of the fort with its rotten wooden beams and that as a result the artillery had been dismantled and rebuilt on the beach. But the castle was probably still not repaired before 1638.

In 1642, at the beginning of the English Civil War between the supporters of King Charles I and those of Parliament, Sandgate Castle was taken by parliamentary troops, although the captain of the fort, Richard Hippisley , remained at his post. The civil war initially ended in 1646, but flared up again after a few years of unsteady peace in 1648. Parliament's naval forces were stationed in Kent and had Device forts at Deal Castle, Sandown Castle and Walmer Castle for their protection , but by May the royalist uprising was underway across the country and the navy joined the rebellion. Sandgate Castle and its sister forts were captured by the royalists. The parliamentary troops put down the further uprising at the Battle of Maidstone in early June and sent a force under the command of Colonel Rich to the Kentish forts. Sandgate Castle was still occupied in August of the same year when Rich sent forces there to prevent it that the garrison there intervened and disrupted his attacks on Deal Castle and Sandown Castle. Soon after, however, it was recaptured.

During the Interregnum, Hippisley initially continued to be the captain of Sandgate Castle until he was replaced in 1653, which led to a complaint on his part that he had been treated unfairly and that Parliament owed him money. During this time the garrison was expanded to include a governor, two corporals, 20 soldiers and three riflemen. When Charles II came to the throne in 1660, Sandgate Castle and the other Device Forts initially remained the core of the defenses on the south coast, but by then their construction was already out of date. The garrison was trimmed back to pre-civil war levels and then further reduced to just ten in 1682. Sandgate Castle was now in very poor condition and in 1663 £ 200 had been released to repair the fort, partly financed by the transfer of lands confiscated from former supporters of the Parliamentarians around Sandgate.

19th century

Sandgate Castle was still in use during the Coalition Wars at the beginning of the 19th century, but was largely rebuilt. Brigadier General William Twiss reported on the south coast in 1804 and proposed the construction of a series of 58 new defense towers along it. As part of this work, Sandgate Castle was to be converted into a "safe marine battery". After some contradiction and many delays within the War Office , work on the castle finally began in 1805.

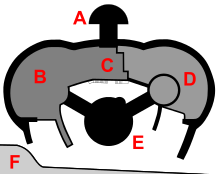

In the course of this project, the height of the fort was significantly reduced, which destroyed a large part of the defenses. The upper floors of the donjon, towers, covered walkways and gatehouse were all demolished, along with some buildings in the inner castle. The rubble obtained in this way was used to backfill the outer bailey, raising its level and turning the inner courtyard into a moat . The height of the inner curtain was reduced to one floor and the outer curtain was newly clad. An esplanade and a battlement were built around the remaining outer curtain wall, on which at least eight gun emplacements were placed.

The circular donjon was converted into a Martello tower , a kind of Napoleonic artillery fortress. This was now only two stories high, even if the inner walls and passageways remained almost undamaged. Access was on the upper floor via an unusual, sliding drawbridge that ran on rails and could be pulled back into the ground. The different floors were connected by spiral stairs. The basement of the donjon housed an artillery magazine made of bricks , and on the roof, supported in the middle by a pillar that ran the entire height of the building, was a single gun post.

The north-east and north-west towers, which were now only one storey high, were planted with lawn, transforming the rear part of the outer courtyard into a flat, grass-planted esplanade. The height of the south tower was reduced to two stories, but still served as a gun platform. The covered corridors between the donjon and the towers were now only one story high and connected the sunken towers in the northeast and northwest bastions. The upper floors of the gatehouse were rebuilt, while the ground floor remained in its original state from the 16th century.

The changes to the castle were finished in 1808. The fort was equipped with eight 24-pounder cannons along the outer wall, as well as another gun on the roof of the south bastion and one on the donjon. The new castle offered space for a garrison of 40 men.

In 1859 the fort was re-equipped with heavier artillery, a combination of 32-pounders and 68-pounders. A new magazine was built, consisting of a large brick building divided into three rooms for storing gunpowder and specially designed to keep the gunpowder dry. The outer gun stations were also rebuilt, using the foundations from 1806 again. The two gun positions in the north-west and north-east bastions that have survived to this day date from 1859.

Coastal erosion remained a problem. In the middle of the 19th century the floods reached the southern edge of the castle and a status report from 1866 indicates that the walls had been washed away by the sea. Despite the installation of protective pillars around the castle, it was badly damaged by the floods in 1875 and 1878, which led to serious cracks in the masonry. The high maintenance costs combined with the dwindling usability prompted the government in 1888 to sell the castle to the South Eastern Railway , which wanted to convert it into a train station. It was then sold to private individuals and a small museum was set up in it, which from time to time was opened to the public for the price of a penny.

20th and 21st centuries

The retreating coastline continued to threaten Sandgate Castle, and heavy storms in 1927 and 1950 undermined large parts of the castle. When a new wall facing the sea was built in the early 1950s, the southern third of the castle had already been completely destroyed.

In 1975 Peter and Barbara McGregor began restoring the ruins of the fort with support from the Department of the Environment , Kent County Council and the British Army . As part of this project, research was carried out between 1975 and 1979 by archaeologist Edward Harris . The part of the esplanade from 1806 around the northeast bastion was excavated, revealing the lower-lying brickwork of the tower from the 16th century and the east side of the magazine from 1859 and a retaining wall was built to secure the newly discovered walls. This created two levels of the outer bailey, a higher one on the west side and a lower one on the east side. The donjon was converted into a private house and a new winter garden was built on its gun platform. 2000 bought Geoffrey boat and his wife the castle, from Boots Company, today AMT Southeastern Ltd. , is used.

English Heritage has listed the castle as a First Grade Historic Building. The two main books of the original building from the 16th century, written by project scribe Thomas Busshe , are now in the British Library . They are 350 pages long and form, as the historian Peter Harrington describes it, "the most complete building records of a fortress from the Tudor period".

Individual references and comments

- ^ MW Thompson: The Decline of the Castle . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1987, ISBN 1-85422-608-8 , p. 111.

- ^ A b John R. Hale: Renaissance War Studies . Hambledon Press, London 1983, ISBN 0-907628-17-6 , p. 63.

- ^ DJ Cathcart King: The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History . Routledge Press, London 1991, ISBN 0-415-00350-4 , pp. 176-177.

- ^ A b B. M. Morley: Henry VIII and the Development of Coastal Defense . Her Majesty's Stationary Office, London 1976, ISBN 0-11-670777-1 , p. 7.

- ^ Peter Harrington: The Castles of Henry VIII . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-1-4728-0380-1 , p. 5.

- ^ John R. Hale: Renaissance War Studies . Hambledon Press, London 1983, ISBN 0-907628-17-6 , pp. 63-64.

- ^ John R. Hale: Renaissance War Studies . Hambledon Press, London 1983, ISBN 0-907628-17-6 , p. 66.

- ^ Peter Harrington: The Castles of Henry VIII . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-1-4728-0380-1 , p. 6.

- ^ Peter Harrington: The Castles of Henry VIII . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-1-4728-0380-1 , p. 11.

- ^ Steven A. Walton: State Building Through Building for the State: Foreign and Domestic Expertise in Tudor Fortification. In: Osiris. Issue 25, No. 1 2010, p. 70.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 54-55.

- ↑ WL Rutton: Sandgate Castle, AD 1539-40. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 20 1893, p. 229.

- ^ Steven A. Walton: State Building Through Building for the State: Foreign and Domestic Expertise in Tudor Fortification. In: Osiris. Issue 25, No. 1 2010, p. 71.

- ^ A b Peter Harrington: The Castles of Henry VIII . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-1-4728-0380-1 , p. 18.

- ^ A b c d Andrew Saunders: Fortress Britain: Artillery Fortifications in the British Isles and Ireland . Beaufort, Liphook 1989, ISBN 1-85512-000-3 , p. 46.

- ↑ WL Rutton: Sandgate Castle, AD 1539-40. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 20 1893, p. 235.

- ^ A b c d e f Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, p. 81.

- ↑ a b W. L. Rutton: Sandgate Castle, AD 1539-40. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 20 1893, pp. 234-235.

- ^ A b Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, p. 55.

- ↑ WL Rutton: Sandgate Castle, AD 1539-40. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 20 1893, pp. 235-237.

- ↑ Tim Darvill, Alan McWhirr: Brick and Tile Production in Roman Britain: Models of Economic Organization. In: World Archeology. Issue 15. No. 3 1984, p. 250.

- ^ Peter Harrington: The Castles of Henry VIII . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-1-4728-0380-1 , p. 8.

- ↑ Martin Biddle, Jonathan Hiller, Ian Scott, Anthony Streeten: Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological, Structural and Historical Investigation . Oxbow Books, Oxford 2001, ISBN 0-904220-23-0 , p. 12.

- ↑ a b c d It is difficult to compare costs and prices in the early modern period with today's costs and prices. £ 5584 of 1540 can be worth between £ 3.1m and £ 1.5bn in today's money, depending on the scale used, £ 260 of 1616 between £ 44,000 and £ 13.6m, £ 560 from 1623 between £ 93,000 and £ 27.7 million and £ 200 from 1663 between £ 26,800 and £ 6 million. As a comparison, the total royal expenditure on the Device Forts throughout England in the years 1539–1547 £ 376,500, with e.g. B. St Mawes Castle alone devoured £ 5018.

- ↑ a b c d e Lawrence H. Officer, Samuel H. Williamson: Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present. MeasuringWorth, 2014, accessed August 24, 2016 .

- ↑ a b c Sandgate Castle. Historic England. English Heritage, accessed August 24, 2016 .

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, p. 74.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 72-73.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, p. 68.

- ^ A b c d e f g Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, p. 54.

- ^ A b c Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 81-82.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, p. 80.

- ↑ WL Rutton: Sandgate Castle. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 21 1895, p. 244.

- ↑ WL Rutton: Sandgate Castle. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 21 1895, pp. 244-246.

- ↑ a b c W. L. Rutton: Sandgate Castle. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 21 1895, p. 248.

- ↑ a b W. L. Rutton: Sandgate Castle. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 21 1895, p. 247.

- ↑ WL Rutton: Sandgate Castle. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 21 1895, pp. 248-249.

- ↑ a b W. L. Rutton: Sandgate Castle. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 21 1895, p. 249.

- ↑ a b W. L. Rutton: Sandgate Castle. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 21 1895, pp. 249-250.

- ↑ a b c W. L. Rutton: Sandgate Castle. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 21 1895, p. 250.

- ↑ WL Rutton: Sandgate Castle. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 21 1895, pp. 250-251.

- ^ Peter Harrington: The Castles of Henry VIII . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-1-4728-0380-1 , p. 50.

- ^ DE Kennedy: The English Naval Revolt of 1648. In: The English Historical Review. Issue 77. No. 303 1962, pp. 248-252.

- ^ DE Kennedy: The English Naval Revolt of 1648. In: The English Historical Review. No. 77. No. 303 1962, pp. 251-252.

- ^ Robert Ashton: Counter-revolution: The Second Civil War and Its Origins, 1646-8 . The Bath Press, Avon 1994, ISBN 0-300-06114-5 , p. 440.

- ^ A b Peter Harrington: The Castles of Henry VIII . Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-1-4728-0380-1 , p. 51.

- ^ Robert Ashton: Counter-revolution: The Second Civil War and Its Origins, 1646-8 . The Bath Press, Avon 1994, ISBN 0-300-06114-5 , p. 442.

- ^ Charles RS Elvin: The History of Walmer and Walmer Castle . Cross and Jackman, Canterbury 1894, pp. 110-111.

- ↑ a b W. L. Rutton: Sandgate Castle. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 21 1895, p. 251.

- ^ A b Howard Tomlinson: The Ordnance Office and the King's Forts, 1660-1714. In: Architectural History. Issue 1 1973, p. 6.

- ^ Sheila Sutcliffe: Martello Towers . Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Rutherford 1973, ISBN 0-8386-1313-6 , p. 55.

- ^ Sheila Sutcliffe: Martello Towers . Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, Rutherford 1973, ISBN 0-8386-1313-6 , p. 58.

- ^ A b Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 72, 81.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 65, 68.

- ^ A b Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, p. 66.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 73, 77.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, p. 77.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 73, 77, 81, 82.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, p. 56.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 84-85.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, p. 73.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 54, 60, 66.

- ^ A b Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, p. 82.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 82, 86.

- ^ Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 70-72.

- ↑ a b c Deodato wallpaper, Edward Bromhead, Maia Ibsen, Nicola Casagli, Claudio Margottini (editor), Paolo Canuti (editor), Kyoji Sassa (ed.): Landslide Science and Practice . Volume 6: Risk Assessment, Management and Migration . Chapter: Coastal Erosion and Landsliding Impact on Historic Sites in SE Britain . Springer Verlag, Heidelberg 2013, ISBN 978-3-642-31319-6 , p. 456.

- ↑ a b c W. L. Rutton: Sandgate Castle, AD 1539-40. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 20 1893, p. 253.

- ↑ A penny in 1900 is roughly £ 0.48 today.

- ^ Charles G. Harper: The Kentish Coast . Chapman and Hall, London 1914, pp. 316-317.

- ^ A b Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 53, 86.

- ^ A b Edward C. Harris: Archaeological Investigations at Sandgate Castle, Kent, 1976-9. In: Post-Medieval Archeology. Issue 14 1980, pp. 53, 56, 86.

- ^ Bill Clements: Martello Towers Worldwide . Sword and Pen, Barnsley 2011, ISBN 978-1-84884-535-0 , p. 55.

- ↑ Burglar Fails to Break into Geoffrey Boot's Sandgate Castle Home. Dover Express, archived from the original on November 19, 2015 ; accessed on August 24, 2016 .

- ↑ Colorful Past of new MKH Baron Boot. Chad, archived from the original on November 19, 2015 ; accessed on August 24, 2016 .

- ↑ English Heritage: Sandgate Castle, Sandgate. British Listed Buildings, accessed August 24, 2016 .

- ↑ a b W. L. Rutton: Sandgate Castle, AD 1539-40. In: Archaeologia Cantiana. Issue 20 1893, p. 228.

Web links

Coordinates: 51 ° 4 ′ 24.4 " N , 1 ° 8 ′ 56" E